PAWcast: Leadership Changes at Princeton’s Office of Religious Life

PAW spoke with outgoing dean Rev. Alison Boden and the office’s new leader, Rev. Theresa Thames

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Google Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

Princeton’s Office of Religious Life recently saw a transition in leadership, and we thought it would be an ideal time to speak on the PAWcast with the two people passing that figurative baton: The Rev. Alison Boden, who recently retired after 17 years as dean of religious life and the chapel, and the Rev. Theresa Thames, the new dean of religious life and the chapel, who has been associate dean since 2016.

TRANSCRIPT

Brett Tomlinson: I’m Brett Tomlinson from the Princeton Alumni Weekly, and this is the PAWcast, a monthly series in which we interview alumni, faculty, staff, and students about issues that matter to the Princeton community.

At its founding, Princeton University was an institution grounded in faith led by Presbyterian ministers and theologians, and while much has changed in the last 275 years, faith communities continue to play an integral role in the experiences of many students guided in large part by the University’s Office of Religious Life, which supports 17 campus chaplaincies, along with faith-based student organizations and facilities, including of course, the University Chapel.

The Office of Religious Life recently saw a transition in leadership, and we thought it would be an ideal time to speak with the two people passing that figurative baton:

The Rev. Alison Boden, who recently retired after 17 years as dean of religious life and the chapel, and the Rev. Theresa Thames, the new dean of religious life and the chapel, who has been associate dean since 2016.

So Theresa, Alison, thank you so much for joining me.

Theresa Thames: Thanks for having us.

Alison Boden: Thank you.

BT: I’d like to spend most of our time talking about the Office of Religious Life, but I thought it would be helpful to begin by hearing a bit more about the two of you. So you’re both ordained ministers, there are of course many ways to serve, but you’ve found your calling on college campuses. What were your paths to Princeton, and why do you think this campus has been a good fit personally and professionally?

AB: Yeah, this is Alison. When I was graduating from seminary in 1991, I knew I felt called to ministry, but I did not feel called to the local church, and I had an opportunity to do an internship at Union College in Schenectady for one year. So I said, I’m going to try that out, and I couldn’t believe they paid me and called it work. I was just having such a fulfilling time. It really was a great fit. And so I’ve stayed in this line of work. I’ve just finished 33 years of college chaplaincy.

I’ve just loved working primarily with students, undergrads, but grads, certainly staff, faculty, parents, alumni. I love the time of life that it is for our students and the questions that they bring, the life experiences they bring, the curiosity. I love the intersection of the life of the spirit and the life of the mind.

I have a Ph.D., Theresa also has a doctorate, and we’re critical thinkers and we are critical believers, and we get to put that all together in a wonderful way and to make student friendships, students who are trying to do this kind of integrative work also. It’s been so fun.

TT: This is Theresa, and I grew up in what I call the buckle of the Bible Belt in Mississippi, and I had been involved in my local church my entire life, and it was in undergrad, after 9/11, when I decided to go to seminary. And when I went to seminary, I thought I would just be a theologian or scholar. I never saw myself as a pastor in a pulpit because I didn’t see that example growing up. But during seminary, you do an internship and I was serving a local congregation, and as much as I was unsure, the local congregation affirmed all my gifts as a pastor. And so I pastored in the Washington, D.C., area for 10 years. And when this opening came available at Princeton, it really was the marriage of my passions, of pastoral connections with the community, but also being in an academic setting where there are so many questions and new thoughts and ideas that allows us to marry theology and everyday life.

BT: That’s wonderful. And Alison, can you give me a sense of how the landscape of religious life among Princeton students has evolved in the time that you were on campus, to today?

AB: Sure. When I got to campus, it was 2007 and we had two Jewish chaplaincies, large Jewish chaplaincies. One wasn’t recognized yet, so I worked with then-President Shirley Tilghman during that first year to recognize the second of them, which is the Chabad organization.

In my first days on campus, I heard from both Hindu and Muslim students that as they looked at other student religious groups that had chaplains, they saw just how excellent the programming was and the opportunities for students and the clerical presence for students, and they said, “We want to try that too.” So in my first year, posted positions for permanent Hindu and Muslim chaplains, filled those positions, and those have been a total game changer.

When another position came open on the Office of Religious Life chaplaincy staff, I was able to hire someone whose portfolio was to be our interfaith work, multifaith work, and who himself practices Buddhism and brought in that angle.

So the student body has been diversifying religiously for decades now, and that’s been true on the religious front as well. And so we’ve been responding to that in the Office of Religious Life. There are more and more student religious organizations that bring in perspectives, either whole new traditions that aren’t represented by chaplaincies. It’s not a sort of a clergy-based kind of tradition, but more and more of those. And then others are offshoots of organizations that already exist, but they are groups of student friends who really want to do their thing their way. That’s beautiful.

So it’s just been a real flowering and an expansion of communities and traditions. It’s been mirrored by our peer schools. This is who’s coming to university in the United States. It’s been very exciting.

BT: And Theresa, we’re speaking in August. It’s pretty quiet on campus right now, but we’re only a little more than a week away from the next class of undergraduates arriving. How are students introduced to the Office of Religious Life and the programs and communities that you represent?

TT: The Office of Religious Life, our chaplains and our students, take part in the opening exercises, and even before our chaplains and students get to opening exercises, many students who are involved in the Office of Religious Life serve as leaders in programs that first year students participate in. They serve as community advocates, counselors, and so our students are all over campus talking about the Office of Religious Life, and so by the time the first day of class starts, they’ve had a touchpoint at some way along the way of orientation to the Office of Religious Life.

And so it’s a great way that the students tell the story of the office, and the depth and breadth of diversity of the students really allows the office to be painted in a broad picture more than just worship services or religious groups, but a place of community and gathering.

BT: And from past experience, what’s the sort of response that you get? Do you hear a lot from individual students?

TT: Oh, absolutely. Students are always curious. They’re curious. Either they’ve come from a faith tradition or practice and they’re looking for ways to continue that in college, or they’re students who are not related to any faith tradition at all, but they’re looking for a sense of community. We also have the Murray-Dodge Cafe where cookies are baked, and so students find themselves into the building by way of cookies, but then they find their self engaged somewhere in a student group in the Office of Religious Life.

BT: People of course can be spiritual on their own, but for many, the appeal of faith community is the community, the chance to join together, to be together. We’re not too far removed — fortunately, we are removed, but not too far — from a time when that was really challenged during the COVID pandemic. You both served through that time on campus. In what ways did the COVID years and in particular the times when there were restrictions on gatherings, how did those years affect religious life at Princeton, and how have communities rebounded?

AB: In the beginning, in March 2020, we went into lockdown like much of the country and I was looking into a Zoom screen and students were looking into a Zoom screen and we were figuring out how to do church on Zoom or meditation or Bible study or whatever was going on. And I remember it was a few weeks, maybe even a full month into lockdowns and another of the affiliated chaplains on campus said, “I’m beginning to get that maybe we don’t have to do it all, try to make it be exactly like it was when we were on campus, right? We need to adapt here, we need to think about this looking very differently because we’re not sitting together in a room and Murray-Dodge Hall, not at all.”

And so it really caused us to become a lot more creative. What does meditation feel like? What does worship feel like on Zoom? How do we make some new kind of practices come together? Some of it really created changes that we continue to use. We use video conferencing more now even though we don’t have to because it makes it possible to bring in voices from around the country and around the world. We learned that one during COVID, and we’re glad.

I’ll say another thing it’s done has been to just normalize the staying in pastoral contact with alumni, with people who are no longer literally on campus or who are away for the semester or the year, even on the other side of the earth. We’ve got these relationships even stronger because we’re using that technology still.

A number of congregations and houses of worship around the country are having a challenge in terms of attendance of people who just created other practices during COVID. And what I’ve seen on campus is that the numbers within religious organizations are back. This isn’t about getting up on Saturday evenings, Saturday morning, Friday afternoon, Sunday morning, whenever, and getting yourself to your house of worship. We’re all together on campus. It took a little while across campus for students to sort of reintegrate into the levels of participation in everything, but my sense is they’ve really done that now, and certainly with the religious communities we’ve learned a lot, but we’re very much back together in person.

BT: Theresa, does that ring true for you as well? I mean, do you notice the numbers back in the type of participation that you witnessed before the pandemic?

TT: Absolutely. The college experience is about being together and gathering, and once we were able to gather again, we really saw unbelievable numbers of people just wanting to be together.

And I think our office realized that we do so many celebrations in our office — religious celebrations, gatherings of people around sacraments and baptisms and all these things — and our community really missed that. And so the numbers really rebounded because students were isolated for a while, and helping them make connections with one another, but also understanding the campus in person.

BT: If you look at some of the national polling or studies, the overall trend seems to be that attendance at religious services is going down, and that is particularly true among young people. Is that something you’ve seen at Princeton, or is Princeton in some way a bit different from that trend?

AB: I’ve only been at Princeton 17 years, but for 33 years I’ve been looking at this landscape head on and in the middle of it, and what I remember from the early ’90s is we were coming out of a real low point of student participation in religious communities. That was in parts of the ’70s and the ’80s, and by the beginning of the ’90s, we were on an upswing. I started, as I said, in ’91, and it just kept going up and up and up, and I wondered, is this a pendulum thing? Are we going to crest, and then are we going to go back down? We might, or maybe that’s not the right sort of analogy at all, but we haven’t crested yet.

It’s, for those of us in this line of work, just been a happy thing that we continue to get students who are just really, really interested in this work. Princeton, to its credit, makes it as easy as possible to be involved in this kind of thing if that’s what you want to do, just with the plethora of organizations that are out there, the numbers of chaplains who can be of help to you no matter what’s going on in your life.

So I have not seen any kind of drop off. We still experience really good numbers of participation. We may be cresting. I’m going to find out in a few years when I can see into that crystal ball about what it means for where we are now. The pandemic was a big disruption of all that. So what I can say is we are back to pre-pandemic levels and that they’re really healthy.

BT: I feel like Princeton, at least my perception is that the institution has really leaned into the interfaith inclusive vision of religious life for a long time now. How do students see it? Is that something that really appeals to them, to interact with fellow students of different religious traditions, backgrounds, and learn about their faiths and exchange experiences?

TT: Absolutely. There are two groups that we have, and I’ll talk about the Religious Life Council, and Alison can talk about the Rose Castle Society. And this is an opportunity for students to be with one another and do the clumsy work of asking questions, of being curious in a way that in other settings may not be emotionally safe or feel safe for them to ask about a tradition or a way of life. And the intentionality of building the Religious Life Council was just for that, for students of different faiths to come together to ask questions that they were curious about.

And what that does is it allows for our office to interact with students of different years and different backgrounds that’s different from if they were in their identified religious groups.

And so that intermingling is intentional. It’s intentional across, for the Religious Life Council, having a mix of students from different years and different areas. And it’s provided us a model of conversation so that when there are tensions, we have students who are already in conversations with one another that can come back to the table. And Alison’s Rose Castle Society is an extension of that model of conversation and reconciliation.

AB: Yeah, Rose Castle Society is a group of students on campus who have done a particular kind of training on how to do deep listening across very deep differences. I could talk about it for a very long time, I won’t, but it brings together students of every faith and spiritual background, and none, to learn the hard work of how to dialogue across really, really profound differences.

You know, Brett, we have students who come to Princeton eager already to do this kind of work, and that’s fun for us. They seek us out at orientation, and we’re really glad to meet them. And then we’ve got many other students who just didn’t have this on their radar or didn’t even have any introduction to this possibility and then get into it because they see or hear through a friend what’s going on, and then they become very committed.

One of the favorite comments I get from students as they graduate, every once in a while is, “I never thought coming to Princeton that this was how I was going to be actually spending a large part of my free time, but I’ve loved it.” Surprise.

BT: I want to go back to something you said, that there are things that are going to be divisive on campus, and sometimes those relate directly to conflicts elsewhere in the world that are pitting different religious groups against one another. What is the role that the Office of Religious Life can play in facilitating dialogue and understanding in these really difficult times that we’re in one of them now, but that is in some ways not extraordinary, that there are always things to discuss and wrestle with?

TT: Yeah. I would say even the makeup of our office, especially the chaplains, that we come from very different backgrounds and traditions, but we work together in the Office of Religious Life, and one of our colleagues would say, “We are building community, not consensus.” And so what does it mean for us to work together without having to compromise what we believe or our integrity of our faith traditions, but really think about the whole of humanity and how to have empathy, how to be an active listener, how to show concern? And those are the makings of community, compassion. And what I know is that those type of skills are learned, they really are. They’re learned and they are practiced, and we don’t have a lot of spaces where we can practice those skills.

And so our office, we model it in everything that we do. Our colleagues, we really do care for one another, and we’re able to have differences and also come together all the time. And so I love — I could go on and on about how great our team is, but because we live it, we’re able to model it, and students are able to see us, not only students, but our colleagues across campus as well, are able to see how we live in community, but in our very distinct differences as chaplains and as staff.

BT: I think of something that the pastor at my home church says often when students are going off to college, which is, “We’re sorry to see you go, but good news, there are churches where you’re going, you can find one.” Easy for him to say in a sort of a mainline Protestant congregation, but some traditions and faiths may not have as much of a kind of critical mass in Princeton’s student population and campus population. What can you do to make those students feel welcome and in community if they don’t have 20, 30, 40 or more people who come from the same background?

AB: We have any number of groups who nope, don’t have 20, 30, 40, but they get three or four and they are really, really committed. And we work hard at preview days during orientation, I mean through, it’s old school, but it works, our website to do all that connection. And what I’ve always said to students is if you are looking for something in terms of religious life and it’s not here yet, talk to me, because I’m also hearing from other people like you, right? And I can be that connective tissue for you. And in that way, we have helped people from really small traditions come find one another.

Some of those students write to us before they get to campus, which is helpful because before they get to campus, I can put them onto a sophomore or junior or just help them find the small but critical mass that already does exist here. Or as I did two summers ago, there had not been critical mass, but they were making it, and so we got them to be a recognized organization, and they’re doing really well.

BT: At the beginning, you both talked about working with students in this age group specifically. What do you learn from them, what do you take away from their experiences that informs your work going forward?

TT: I say that when I come to campus, I want to be the adult that I needed when I was in college, and this reminder of what it is to be young, what it is to be young at a different time in the world. We’ve never lived in a time like this where there’s instant information. I mean, there’s so much happening at one time. And so I really love working with the students because the questions that they ask may be questions I haven’t even thought of before. So it challenges me to think broader, to think again, to think about inclusion and diversity, to think about voice, to think about perspectives.

And that is what I, when I think about being a local pastor, these questions that students ask, they make me a better pastor because I have to slow down and think again about what I thought I knew. And it’s a learning. I learn as much from them as I think they learn from us.

AB: Absolutely. Particularly for me in terms of culture, but also individual topics. Here’s an example. A few years ago, let’s say five, six, maybe before the pandemic, I just kept hearing all these students talk to me about what they were studying and writing about and their thesis and that sort of thing, and a lot of it had to do with the environment. And I thought, “Wow, I just know a bunch of students right now who are really into the environment,” and then I get it, and it’s like, oh, there’s a generational commitment right here that is a totally new expression. And then I had to start paying attention to where that came from for them and to look even more deeply at how they were expressing it when they got to Princeton, both in their academics and beyond, and vocationally.

I mean, there’s just a group of students who are majoring in every last thing and the environment, and thinking about how to become an environmental lawyer, how to become a scientist, how to become a pastor, how to become everything with this as a primary, primary commitment in all of that. I eventually got it.

BT: I imagine spirituality can really help young people navigate this very difficult period in their lives, challenging times, a challenging place, Princeton, academically challenging, socially, all those things. What do you hope students take away from their interactions with the Office of Religious Life, and how do you hope that they carry this forward?

TT: When we came out of COVID, there were all these ways of how do we bring community, what are the things that students needed. And the one thing that I thought about of how to be embodied, how to be in their bodies and be with one another. And that may seem simplistic, but there’s so many things in society that’s calling us beyond ourselves. And what I hope that our office gifts, and I say the word actually gifts to our students, is permission to be embodied in all the ways that it’s complicated and messy at times and there’s no perfect way of doing it, but being embodied in community with one another, just the gift of that.

And out of all the spaces on campus that’s evaluating and grading and ranking, our office is a place where the gift is us being together. And I want them to continue to lean into being community beyond Princeton.

AB: Absolutely. I hope that when their time with us in person is over, that they’ve really learned how to discern what it is they believe in religious terms, spiritual terms, maybe secular terms, but to really articulate for themselves and own it and claim it, and then also be thinking about how they’re going to live out of it. To have that kind of integrity of belief and action, action and belief, that kind of praxis so that they live that kind of integrated life, which is where I think deepest meaning is found. That’s what I want for them.

BT: We’re recording this for an audience of alumni, so I’m curious if there are any experiences from your time at the Office of Religious Life that you’d like alumni to know about that they might not have heard of, things that stand out in either your day-to-day experience or events that really are particularly meaningful for you that you’d like alumni to know more about?

AB: I’m going to take one from this last year, which has been so fraught with the war in Israel and Gaza, and that’s shown up on all our campuses in different ways and at Princeton too. And we hear about the conflicts on campus around that, but what hasn’t gotten out so much is the moments of grace, of students carrying deep commitments to their communities, to communities with which they feel solidarity, however that’s expressed. And completely very far from the limelight, they have the courage to get together with someone they know disagrees with them greatly, and then to bring a friend with them who’s from their own perspective and do a four -coffee. That’s just never going to make The New York Times, but I’m glad it’s making the PAW because this is the building blocks of living well together.

I just am moved so much by so many beautiful reconciling student initiatives, and I really want you Princeton alumni to know that your successors on campus today are doing beautiful, I think, courageous, generative work of doing some really deep listening, even on the most difficult topics to them.

TT: One initiative that one of our colleagues spearheaded is a program called Hidden Chaplains, where students nominate someone in their life on campus that they see as a chaplain that doesn’t hold the official title as a chaplain, whether it’s the person that scans them in or their TA or just anyone in the campus community. And each year these staff members come in and they come with their families and loved ones and these students stand up in gratitude saying why they nominated this person. And there’s not a dry eye in the room because it’s — you’ve made this place home.

And all the ways that our students are thinking about their experience, not just them as students, but their connection to the faculty and staff, especially those who work in building services and facilities and all the ways that our students do not take that for granted. It’s a beautiful way of our students calling out people who’ve made this place amazing for them. And that program is just a celebration of what does it mean to make Princeton home for a time being.

BT: Those are great. Both excellent examples. I think I’ve reached the end of my list of questions. I wanted to give you each the opportunity to either go back to something or comment on anything that we’ve missed. Is there anything that we haven’t touched on that you were hoping to speak about?

AB: I’m in a position departing from Princeton and also from a long-time career that started before Princeton of just feeling such gratitude, and to Princeton for making religious life so strong on campus. We do what we can within the office, but the institutional support is critical and it is there, and it has a transformative impact on any number of our students in the best of ways. So gratitude, gratitude to the institution is what I want to end on.

TT: And I echo that: gratitude to our colleagues across campus who’ve served as partners to us in all of the ways that we are able to do the work that we do. They see that we’re helping people make meaning, and it’s just, we’re not an afterthought. We really are seen as partners in what does it mean to do campus life here, and it’s a great place to be able to do what we get to do. It’s a privilege.

BT: Well, thank you both for joining me. It’s been a real pleasure.

TT: Thanks, Brett.

AB: Thank you.

PAWcast is a monthly interview program produced by the Princeton Alumni Weekly. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, and SoundCloud. You can read transcripts of every episode on our website, paw.princeton.edu. Music for this podcast is licensed from Universal Production Music.

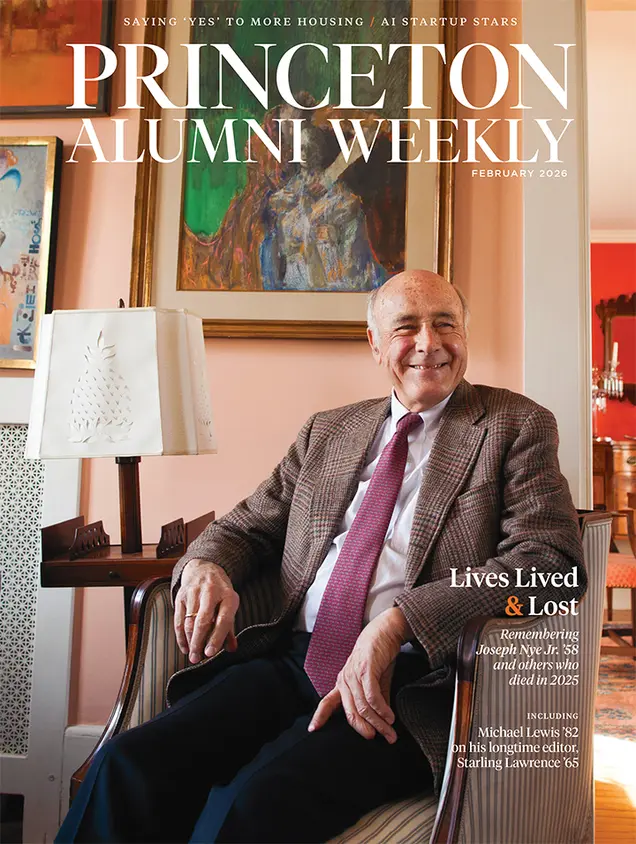

Paw in print

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

No responses yet