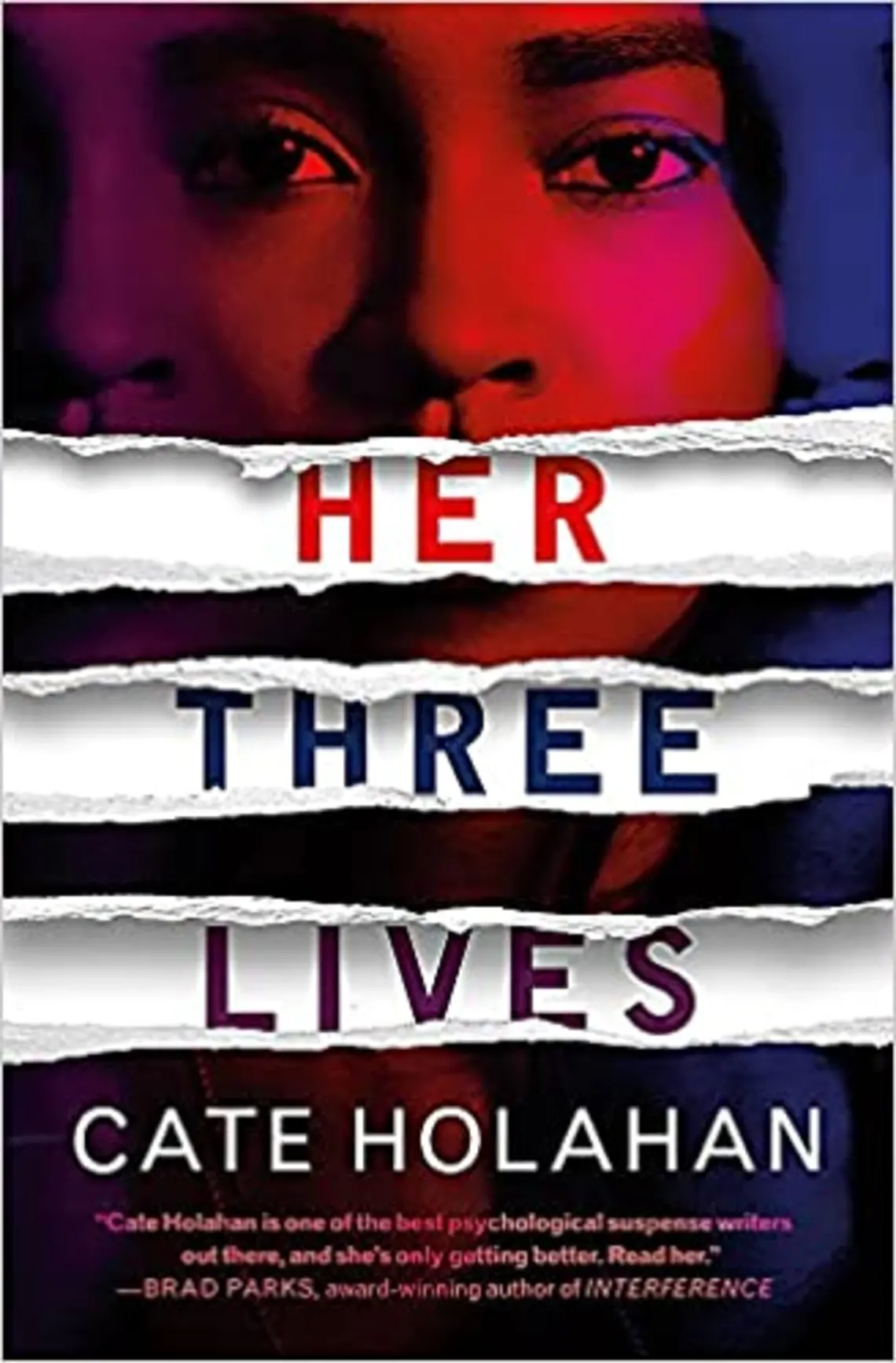

PAWcast: Novelist Cate Holahan ’02 Probes Psychology in Domestic Thrillers

‘That adage holds true, that every villain is the hero of their own story’

Find more PAWcasts online here

As a journalist, Cate Holahan ’02 covered some dark stories, like the Bernie Madoff scandal. Today, she uses what she learned to write domestic psychological thrillers. Karma always comes for her characters, but there are no perfect villains, and no one emerges a complete hero. In her fifth and latest book, Her Three Lives, Holahan probes the way security technology can twist a mind pushed to the edge by violence and paranoia.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Google Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

Liz Daugherty: A violent attack by an unknown assailant lands a wealthy and powerful architect, 52 years old, in the hospital. Then, back home with his 32-year-old fiancé, paranoia begins to consume Greg. He installs cameras throughout the house and begins spying on Jade, who’s trying desperately to keep her own secrets. Meanwhile, Greg’s ex-wife and two adult children begin planting seeds of doubt that the love the two thought they shared might not even be real.

This is Cate Holahan’s latest novel, Her Three Lives. Holahan specializes in domestic, psychological thrillers, inviting her readers to tumble down the dark paths she creates. Cate spoke with PAW about her career as a writer, this latest work, and why she and her readers love this tortured genre.

Cate, thank you for joining me!

Cate Holahan: Thanks for having me.

LD: Your book kept me up reading when I should have been sleeping.

CH: Good! Yeah, that’s what you like to hear.

LD: So, tell me. How did you come up with the story behind Her Three Lives?

CH: Yeah, well, you know, I always joke that I write from a place of anxiety, so anything that bothers me and has me thinking usually becomes the germ of a story idea. So with this one, I was thinking of all of these cameras that so many of us have — that I have. The Nest cams, and the Ring doorbells, and the — all the assistants. You know, Alexa and Google assistants, and just how much spying you could kind of unintentionally do on your own family, in the interest of securing your home and keeping everyone safe. And it really came about because I had these cameras for when my kids were young, you know, to kind of make sure that nobody woke up in the middle of the night, and takes a tumble down the stairs or whatever. And now they’re older. They’re 9 and 11, and if they get into an argument, I find myself saying things like, “Well, you know, I can go to the tape. I can see who started it.” And then I thought, Wow, that has to be damaging. (laughs) You know?

And so I started to think, well, what if you were in a situation where there’s — this couple has a violent attack, and they do everything they can to kind of secure their home, particularly Greg, who was struck on the head with a crowbar and ends up suffering a traumatic brain injury. So he’s really stuck in the house. He has a helmet on. And so he doesn’t feel physically capable of really defending his home, so he’s doing it, to the best of his ability, electronically. And then he starts inadvertently spying on his wife, which leads to more deliberate spying on his wife, as he starts to suspect that maybe she had something to do with this break-in that nearly cost him his life.

And so, yeah, it really just came from my unease with all of this technology, and even how I was using it, and then I thought, well now, who would be like, two of the worst people to have access to this technology — to all of this, and be suffering from a kind of trauma that might lead them to abuse it, and that — that really was the genesis of the book.

LD: Oh, that’s really interesting. It does — it plays quite a big role in the paranoia, and I’ll tell you, I was very creeped out at the way Greg was talking to her through the cameras and the speakers. It felt very unnerving.

CH: That’s the tension, right? Is that it’s changed the way we interact with one another. And not necessarily for the better, but it’s also very convenient, right? And so — and in this book, you know, Greg, he has balance issues after he was hit in the head, so his natural thing, instead of going from room to room in this large house, is just, well, use the intercom system. Which, it makes perfect logical sense, but there is unease and this like — it’s dehumanizing in way, when you’re living with somebody and yet you’re speaking to them through technology.

LD: So let me back up a little bit and ask you about your career and how you got into this. So you were a newspaper reporter?

CH: I wrote for The Record newspaper, and then after that I was at Business Week for a while, I covered technology and internet advertising. And so that was really the genesis of my writing career, and then I moved from there to being a producer at CNBC for a bit, and finally when I had my second kid, I realized the breaking news schedule wasn’t really conducive to me having younger children, and I’d always written fiction on the side, and so I said, OK, well, let me just buckle down and really just make this my full focus other than the kids. And then, see if I can go anywhere with it. And so, I wrote that book and I got an agent, and that was Dark Turns, and then now I’m five books later, and I have contracts for two more coming out next year, and that’s how it happened.

LD: I think a lot of people would love to become a novelist. It’s sort of their secret ambition. Most people don’t really make it happen. So it’s interesting to me that you did, you know? And I guess maybe having the groundwork already laid with having already done some writing probably helped you make that transition?

CH: Absolutely. I mean, you know, my agent refers to it as, journalism is playing your scales. Even though it’s a different kind of writing, you’re playing your scales every day. You are used to just waking up and needing to write, no matter what. You know, at Business Week, we had to do one to two online articles for the online property, and then like an overarching magazine story for the end of the week, usually expanding on one of the stories you’d written. So you just get used to kind of that discipline, that I write every day.

And I thought that was really helpful when I went into fiction writing, because I didn’t sit there and go, “Oh, I have writer’s block today, I’m not feeling inspired.” I would write, and then sometimes I’d delete what I wrote — it was like, that chapter’s not going to make it in — but I was going to write every day. If you write every day, at the end of a few months, you’ll end up with 100,000 words.

The other thing that I think hurts journalists when they want to do it is, if you’re writing every day, it is then hard to go home and write more. Right? You’ve already put out 3,000 words into the world, and then you’re going to go home and write another 1,500. And so I got a good piece of advice, which was a little painful to hear, when I had been writing on the side. I went to a conference, and there was an author, and he said, “I do this every day for six hours a day, and it’s just fiction,” and so he said, “and when you’re trying to break in, you’re competing with me.” Because you are. It’s just that they already have their stable of writers, and so you’re trying to get in there, and I do think it really didn’t happen for me until I took that year off, and I said, OK, I’m going to focus on it, because I am competing with people where this is what they do — that’s what their focus is all day.

LD: I think, also — and I think you’ve spoken about this a little bit before, that as a journalist, you write about some dark things sometimes, but they’re true stories. So now, you’re again writing about some dark things, but it’s fiction. So I think there’s a little bit of a link there, maybe, as well?

CH: Oh, absolutely. I think also, it’s a way where I get to control the ending. So I can have this catharsis of it ending in a way that’s neat, where the guilty are punished, and the — and the victims have some sort of resolution, which, you don’t get that satisfaction when you’re writing for journalism. At one point, I was covering — this was a brief period where I was working for MSN Money, and the whole Bernie Madoff scandal happened. And I was interviewing his victims, and it was — oh boy, it was just so depressing, because there were these people that just, they had lost everything. There was one woman who, she had had early-onset Parkinson’s. And so she had retired and put her entire retirement savings with Madoff, because she had heard that he’s kind of — he’s a diligent, safe investor, and you’ll get 12 percent a year, and — and so she did it, and lost everything. And she had an adopted child, who all of a sudden she was worried — like, how am I going to take care of this person, because I can’t work. I have Parkinson’s.

And so — and then the story just — you write the article, and then you go and you kind of — it’s not resolved for years, right? So I get to write — in The Widower’s Wife, where there’s a bad financial actor, and at the end, it’s very satisfying, if I do say so myself.

LD: I found that in a talk that you gave to the Rocky Mountain Fiction Writers. And I thought that that was — you put it really well. You said, “It satisfies a sense of justice that so many of us feel isn’t sufficiently present in our real world.”

CH: The one challenge for me, as a writer, is you can never write villains that you don’t somewhat sympathize with, because the — that adage holds true, that every villain is the hero of their own story, right? And so you have to kind of connect with what is it that’s driving them to do these bad acts. And if you do it well, at the end, when you punish them — cause they deserve to be punished, but like — and it — and the story resolves, you do feel bad, to some degree, because it — you had to understand something.

I mean, even with Madoff, as awful as it was, and he destroyed so many people’s livelihoods and their savings, I’m sure in his mind, he was the hero of his family. He created all this amazing wealth for his family, and he was generous with friends, and I mean, that was his psychology. And so you do have that tension as an author, of how do you resolve it in a satisfying way, but also recognizing that all your characters are human, and there’s always something redeeming about everybody.

LD: I think that makes a much more satisfying storyline, because you get those layers of complexity that really keep you thinking. That was one of the things I noticed when reading Her Three Lives, is that it really felt like anyone could’ve done it. You know? And I’m running through all of their motives and all of their thinking, and I just couldn’t figure out who it was going to be. And that’s why I couldn’t put it down.

CH: Oh, thank you. That’s good. That’s great to hear, because every now and then, you get a reader that’s just like — they just want to know. And it’s a different genre. I think that people love police procedurals because they kind of know, the policeman, even if they’re tortured or whatever, is probably the good guy, and they can feel safe about that. And the deal with psychological thrillers is that every character could be the antagonist, right? That’s — and so, it’s an unease, where you’re seeing it through their eyes, and you want to sympathize with them, but at the end of the — you also know that they’re flawed in a way where maybe they could’ve done something horrible. And that’s a tension in there.

LD: And none of the characters were a hundred percent likable. That was something else. They all had something redeeming, but they all had something where I was like, I don’t a hundred percent love you. And again, that kept it very interesting.

CH: Good. Well, I’m glad. That’s a tension — there are people that they want to a hundred percent love the character. You know? They want — and psychological thrillers aren’t really the best for those readers, because that’s the whole thing, is that you’re not creating people that someone would necessarily be best friends with, because ideally that person that’s your best friend, probably is not going to find themselves in a murder mystery. Right? I kind of feel like most people who find themselves in those situations, you know, they’ve made some mistakes. They’ve associated with people that have some issues, and there’s a reason why they’re in those situations, and it doesn’t happen to the majority of us.

LD: Can you talk a little bit about how you research characters and settings for your books, to give them that feeling that these could be real people?

CH: Yeah. Well, I interview people. I mean, that’s another great holdover from journalism, is that lack of shame. You can just walk over to anybody and go, “Hey. I’m writing something.” “And you seem like you’re the person to talk to.” And so I’ve done that with a lot of books. I will — I mean, I’ll interview detectives when I’m writing that kind of a character. In this case, I interviewed people that were surgeons about how they go about the kind of operations. I interviewed architects. Because there is a certain — different industries lend themselves to different egos, and different kind of ways of being. It doesn’t mean that everybody in the industry is like that. But there’s kind of like a prevailing attitude, and even people that don’t have that attitude feel like maybe they’ve had to kind of adopt it to a certain degree.

So I wanted to get into the psychology of somebody who has had a lot of success as an architect, who’s designed skyscrapers, so he’s a big shot, and kind of the ego that would be involved in a person like that. And then, what happens when you take away a lot of their agency because they’re stuck at home recovering from a traumatic brain injury. Because you’re always looking for the person that would be the worst-equipped to deal with the situation in a thriller. You know, if it’s me, and I lack some agency, I spend most of my time sitting by myself writing. It’s kind of like — I’m going to be fine. You know? But then there’s somebody else used to controlling their world and kind of molding it in a certain way, that might be less fine.

LD: I think that’s interesting, that you go out and you’re interviewing, getting into their worlds. And you’ve talked before about doing that even more — you want to talk a little bit about when you took all those ballet classes for a previous book? Because I thought that was really interesting.

CH: Well, because the first book — the first version of that book that I wrote — I had gotten an agent with it, but it didn’t get published. It had a younger villain. I kind of had this very immoral middle school student. And my agent said, “You know, I think people are just uncomfortable with that, with the bad seed thing. Why don’t you make it a teenager, because everyone believes teenagers are evil?” And so I said, OK, but I wanted to then, if I was going to change it, have — create a scenario where those kids would be naturally competing, and maybe put in competitive situations that were a little beyond what most kids are facing in that high school scenario.

And so I thought, well, I’ll make it this really competitive dance program where they’re all going for the same spots in shows, and then that’s going to lead them into conservatories for college, and so it would be a little bit more cutthroat. And then I realized I had no idea what that world looked like, so I joined this dance class, which was all former ballerinas who had been in national productions, or at least — I think the one that had the least amount of experience had still danced in college. And so I took the class to interview them, and also just to have some understanding of the physicality of doing that every day for hours, and how exhausted you would feel, and what it does to your body, and then also on top of that, because there’s a certain aesthetic look to ballerinas, they have to be very careful with what they’re eating.

And so I kind of put myself through that for a year, which I thought really enriched the characters and made them — and I heard from some dancers that read the book that I got the ballet right. That I got that atmosphere right. So that’s always — feels good. And I owe that all to everyone I took the class with.

LD: That would make it very authentic, you know. If someone who’s in that world can read your book and say, “Yeah, that’s it.”

CH: That was my hope. And they did put me in the recital. Way, way, way in the back. Because all the real dancers — and then I was there as like a token, because I was in the class. And it is amazing. It is hard to plié. Everything, every movement has to be so articulated. And that’s just not how I think. I mean, I’m constantly a hunchback. So, yeah, it was interesting. But that’s probably the most research I ever did, because now that I’m on a book year schedule, there’s no more year of research. It’s like, get it done.

LD: So let me ask you about something else that I heard in that talk, which is that stories should have something to say. And for example, in Her Three Lives, there’s a strong thread in there about how damaging racial stereotypes can be. So I was curious: How have you tried to do that with this book, and why do you think it’s important that your books have a broader message, if that’s the right word?

CH: Writers are divided on this. Some writers are just like, “Ah, just entertain them. That’s all we’re here for.” And I do try to mostly just entertain. But I think that all characters have different aspects, and all of us have — it’s not exactly a political life, cause I’m not making a political statement. It’s more just, we’re dealing with the constructs of our society, and that affects our lives. And so I don’t feel like I’m making genuine characters if that doesn’t exist at all in the story.

So in this case, I have — with Her Three Lives, I have a mixed couple. I’m biracial, so I grew up with mixed parents. My mom’s Jamaican and my dad’s Irish. And in this case, there’s also an age gap between this couple, and he has adult children who are kind of suspicious as to why a younger woman would be involved with their father. And she’s secretive about certain things in her background because she feels that it’s going to play into these unfair stereotypes that his kids — and maybe even Greg, to an extent — have about her. About that she only wants him for his money, or that if she’s somehow involved with him, that there has to be something more nefarious going on, because people don’t date cross-culturally because of love, it has to be all these other things. And I obviously don’t believe that, but that is one of the undercurrent themes that can dictate some of their behavior.

And I do think with stereotypes, people are very conscious when they feel that they’re being stereotyped in a certain way, of not falling into that box. And then how does that knowledge affect behavior? I know for me, for example, my kids are — so my dad’s Irish, and my husband’s Swedish, and somehow the Jamaican just kind of got passed over, and my kids ended up with blue eyes and blonde hair, and pretty fair. And I’m constantly going out there and people think I’m the nanny, because I’m much darker than they are. I do think if you look at their faces, you can see me, but I think people just see the overall coloring impression, and I’ve had scenarios where even once, I was stopped by the police for rolling a stop sign, and at the time, I guess, they were looking for a lot of undocumented nannies, and they said to me that they would take these kids. And I was like, “These kids — you mean my kids?” And so — but I remember after that, I was thinking, “Oh my gosh, I have to stop going out of the house in sweats,” because in my head, there was this feeling of, I need to make it more clear that I’m their mother, and I’m a working professional, because I don’t want to fall into this box of someone seeing a darker-skinned woman than my kids in sweatpants, and automatically putting all this stuff on me. You know?

And so that is definitely a theme in that book. But I try to do that with a lot of books. I have another — with The Widower’s Wife, she’s — the main character is a first-generation American and her parents are immigrants, and they’re — well, they were undocumented immigrants and they’re deported. And I really wanted — I wanted that cause I wanted a character that, for reasons of the story, really wouldn’t have a support system, so when things start to fall apart in her life, doesn’t have a family’s house that she could run to, or — Disney always does this, just kill the parents off. I deported them. But because I needed this person to be kind of on their own. But if I’m going to do that, I can’t then just have that happen and ignore some of the political conversations around what happens to people when their parents are deported but they are an American, and how that affects a family unit.

LD: That’s interesting. I think it makes for, again, a more complex book when you hit on some of these broader themes. It feels a lot like what they tell you in journalism, which is that you need to teach and preach. Right? You need to do the entertaining, but you want your reader to come away feeling like they really got something out of it as well. So it makes for a much more satisfying read.

CH: Thank you. And I do try in it not to really hammer home a political viewpoint. It’s more like it’s just that I think we all live in a certain landscape, and you have to reflect that landscape. I’m writing one now where it’s about the — it takes place in the pandemic, and the crux of it is that there’s a moratorium on evictions, and this family starts to rent out the top floor of their house, and they start to believe that the people they’re renting to were involved in a murder of their dear friends, and they can’t get them out. Right? And maybe — you know, it’s questionable as to whether the family that they’re renting to actually had anything to do with it, but it’s that tension of these — and it’s not saying that there should or should not be an eviction moratorium. It’s just saying, it exists, and so then what would happen in this kind of a scenario.

LD: Oh, that sounds like it’s going to be really good. There’s a lot of things that you could draw on from the pandemic, I’m sure.

CH: That’s right. I just hope that readers don’t get too annoyed with, “She pulled down her mask,” you know?

LD: We’ve been living it.

CH: Right! That’s summer 2022, so I’m hoping by then, we’ll have enough distance to appreciate it, but it is dicey, cause people might just be like, “Oh no, I’m done, I want nothing to do” — it might take 10 years before we feel comfortable exploring that artistically, so I hope I’m not jumping the gun.

LD: Well, and I need to ask you, because this is the Princeton Alumni Weekly, does Princeton ever appear in your books? In a setting, in a person, in a theme?

CH: You know, I really haven’t drawn on it yet. I really loved Princeton. I had a great time there, and I also — I learned so much. I was a political science major, which, at the time when I went, was where they stuck all the journalists, because you could — you know, all the journalists either went to that or history, because if you were writing about contemporary happenings, and so there was a correlation there. And then you took all the humanities journalism classes as electives, but you couldn’t major in it.

Yeah, I mean, one day I will, but I also don’t want to — I write kind of dark things, and I guess I don’t want to disparage my alma mater. It’s like, I don’t want a murder to happen at Princeton. I want to leave it alone.

LD: I can understand that.

CH: It’s changed. Like, when we were there, we had — the Nude Olympics was canceled when I was there. Which, now, looking back, in this climate, the fact that that even existed — but it did, and yeah, you could totally see an awful murder mystery happening set in the 1980s Nude Olympics.

LD: I don’t know, that sounds like a book to me.

CH: There you go.

LD: Well, listen, we’ve gone through most of my questions. Is there anything else that you want to say, or anything else that comes to mind to include?

CH: It’s been so nice. Thank you for having me, and it’s so great to be interviewed by the PAW.

LD: PAWcast is a monthly interview podcast produced by the Princeton Alumni Weekly. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, and Soundcloud. You can read transcripts of every episode on our website, paw.princeton.edu. Music for this podcast is licensed from FirstCom Music.

Paw in print

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

No responses yet