PAWcast: Valedictorian Genrietta Churbanova ’24 on Princeton, Anthropology, and Research

‘I’m really deeply thankful to … everyone who’s made this experience possible’

Princeton’s newest valedictorian, Genrietta Churbanova ’24, is an anthropology major who spent much of her time here researching Russia-China relations in both the Russian and Chinese languages. On this episode of the PAWcast, she talks about her research, about growing up in both Moscow and Little Rock, Arkansas, and about her extracurriculars — including serving as president of the Student Society of Russian Language and Culture and opinions editor of The Daily Princetonian. Faculty have described Churbanova as a hard worker and researcher, “conscientious to a fault and deeply ethical, someone who’s young, but already producing scholarship that will stand the test of time.”

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Google Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT:

I’m Liz Daugherty, and this is the Princeton Alumni Weekly’s PAWcast where we talk with Princetonians about what’s happening on campus and beyond.

Today I’m speaking with Genrietta Churbanova, Princeton’s valedictorian for the Class of 2024. Genrietta is an anthropology major who has spent much of her time here researching Russia-China relations in both the Russian and Chinese languages. She’s a Russian-American herself, having grown up in both Moscow and Little Rock, Arkansas. And here, she’s been president of the Student Society of Russian Language and Culture and opinions editor of The Daily Princetonian, among her extracurricular activities.

The university announcement described Genrietta as a hard worker and researcher. Princeton’s anthropology department chair called her “conscientious to a fault and deeply ethical, someone who’s young, but already producing scholarship that will stand the test of time.”

Liz Daugherty: I’m so excited to talk with you today. Let’s start with a little bit about you. So you spent your childhood in both Little Rock and in Russia. What’s the story there?

Genrietta Churbanova: Absolutely. So my dad is Russian and my mom’s American, and they met in Moscow. But then after they got married, they spent some time in Arkansas. So I first was born in Arkansas, and then when I was around a year old, my family moved back to Moscow. Stayed there for about six years, then moved back to Arkansas. And I would still spend my summers in Moscow to kind of see my dad’s side of the family.

LD: Oh, nice. So you grew up speaking some Russian. So you grew up bilingual?

GC: I grew up bilingual. There are times in my life, I guess, where I didn’t speak English. I still have an early childhood memory of my mom’s mother coming to visit us in Moscow, and I told my parents, “Oh, I don’t want to talk to her. She doesn’t speak Russian,” because I didn’t know English at the time, I guess.

LD: Oh, nice. So where did you pick up the Chinese then, because you’ve been doing your research in both languages.

GC: Yeah. So my school in eighth grade had us choose between learning Spanish, French, and Chinese, and I guess I was just most interested in Chinese at the time. And ever since starting learning it then, I just kind of fell in love with the language. So I’ve kept learning it.

LD: Oh, nice. What do you like about it?

GC: I think it introduced me to a new way of thinking. Maybe that’s partially connected to the language and partially connected, I guess, to the culture that produced the language. So I really felt like I’ve been able to kind of unlock a new way of seeing the world through learning Chinese.

LD: So what drew you to study anthropology?

GC: That’s a really good question. I had a teacher in high school who did her undergraduate education in anthropology or who majored in anthropology when she was an undergrad, so I had some kind of initial exposure to anthropology through that teacher. And then when I came on campus, I attended the virtual anthropology major open house, and I really liked the way the department presented itself. And I think kind of how we discussed that I spent my childhood between Russia and the U.S., I was kind of used to seeing different perspectives on a lot of different issues. And the way that anthropological research methods work, I think really value the ability to see different perspectives. So that discipline really aligned with my personal values and interests.

LD: So tell me about your research, which sounded really interesting from the description that I read of it. Do you want to just sort of launch into it, or do you want to focus in on your thesis first, or tell us kind of how it all came about?

GC: For my senior thesis, I spent about two months in Taipei, Taiwan, working with both the Russian community there and also with Taiwanese people who are studying Russian. And it was a really interesting — I arrived at the topic in a roundabout way because I was initially interested in conducting research on the Sino-Russian border, but for various complicated reasons, that didn’t work out. And then I realized that Taiwan, which is also a Mandarin-speaking locale, had a Russian population. So that was an opportunity to use my language skills and interest in the Chinese and Russian-speaking worlds. And, especially given that there had been a lot of media comparisons between Ukraine and Taiwan and Russia and mainland China, I was interested in how Taiwanese were making sense of the Russians who live in Taiwan.

LD: Did you do that research over the summer? Were you over there?

GC: Yes, it was the summer before senior year.

LD: Oh, OK. So you were interviewing people. How did you do your research?

GC: So I was interviewing people. It was kind of in-depth personal interviews, privileging, or I guess, the quality of the interviews was more important than the quantity. So I got to form pretty close ethnographic relationships with my interlocutors and really got to know a lot about their lives in Taiwan.

LD: Oh, that’s interesting. What did you find out?

GC: I found out that a lot of times, Russians who are living in Taiwan are mistaken for Americans, the implications of which I explore my thesis. And I also learned a lot about how Russians living in Taiwan are making sense of the complicated political reality, especially in terms of Russian political reality at the current time.

LD: Mistaken for Americans, why?

GC: Mistaken for Americans because America’s presence in Taiwan is very strong and there is a lot of U.S. influence in Taiwan. So in my thesis, I explore the idea that American influences in Taiwan is borderline hegemonic, and that influences how people who present as white are perceived.

LD: Did anything surprise you coming out of your research, anything that you weren’t expecting?

GC: I think I was most surprised by the issues that mattered most to my interlocutors in the sense that since a lot of them have been living in Taiwan for 10-plus years, I didn’t think that Russia’s contemporary political reality would be as deeply on their minds as it is. So that was interesting that the fact that spatial distance from Russia didn’t decrease the emotional distance from what’s happening in Russia at the current moment.

LD: Tell me about some of the activities you were involved in while you were here.

GC: Absolutely. So I was involved at the writing center, which I really enjoyed. I started as a writing center fellow in my sophomore year and became a head writing center fellow second semester of my junior year. And I’ve just really loved working with students, conferencing their writing, giving them suggestions both in terms of the broader ideas of their paper and then more micro-level suggestions in terms of structure and analysis. So that’s been a really important part of my Princeton experience.

LD: And you were opinions editor for The Daily Princetonian, which caught my attention. I have seen many opinions inThe Daily Princetonian. What was that like?

GC: It was an interesting job because I had to shuffle both highlighting the columnist’s voice, which was personally very important to me as head opinion editor, but then also ensuring that each piece fit our editorial standards and was supported with ample evidence and had a good combination of both the writer’s opinions, but also a factual basis to support them. And I think working with writing in general can be very challenging and that people get very emotionally attached to their writing. And I think that’s especially true when people are writing about opinions that are very important to them. So it was always an interesting line to walk, making sure to give the writer full control over their piece while still reining in whatever writing-related issues that I wanted to address.

LD: Did you study abroad?

GC: I did not study abroad. I had several summer experiences abroad, but I did not do a semester abroad.

LD: And I was curious about this, so tell me what you think. You were a Russian-American student here on this campus when the war broke out over in Ukraine. I was wondering if you could tell us a little bit about what that was like.

GC: I think it was, at least for me personally first and foremost, deeply shocking, and since then has involved a lot of finding community. And I think that looks different for people from different Eastern European countries and people from different Eastern European communities. But for me, I think that the Society of Russian Language and Culture, which I’ve been president for the past two years, has been a great outlet for finding support through these times.

LD: Would other people here who are Russian say something similar, do you think?

GC: I think it really depends on the individual. I think some individuals have found solace in other community spaces on campus or more clubs that are more directly involved with political activism. We’ve made the strategic choice to keep the Society of Russian Language and Culture more politically neutral. So that hasn’t been, I guess, every student’s go-to in terms of processing these times. But I think for the students that kind of prefer that route, that more neutral space, it has been a good space, a supportive space.

LD: So what’s next for you? What are you going to be doing after you graduate?

GC: I’ll be pursuing a master’s degree next year in global affairs at Tsinghua in Beijing.

LD: Oh, very good. So why did you decide to do that?

GC: So before attending Princeton, I took a gap year during which I was studying Mandarin in Beijing through a different program. And that got cut short because it was the 2019 to 2020 school year. So I was in Beijing when COVID broke out. So obviously, I had to leave before the academic year was up. And I’ve just been really excited looking for opportunities to get back to China since then. And that was kind of what sparked my interest or even gave me the idea to search for such a master’s fellowship.

LD: I can’t let that one go. You were in Beijing when COVID broke out. What was that like?

GC: We kind of went from zero to 100 in the sense that I remember watching the news in Beijing and newscasters were encouraging the Chinese people to stand with Wuhan. But at the time, at least the sense I got is that no one in Beijing was concerned that the pandemic would spread to Beijing. So when people started masking and businesses started shutting down, it was kind of a little bit of a surprise to me. And I was actually on a State Department program, so kind of around that time, late January, we got an email saying, “Oh, don’t worry, it’ll be over soon.” Essentially lock down for a while, but then you’ll get back to life as usual. And then about maybe 48 hours later, we received another email from the State Department saying, “You’re evacuating,” and they had booked us tickets maybe 36 hours after the time that they had sent us the email. So we had 36 hours to get our stuff together and evacuate. So it really went from almost feeling as though the pandemic was irrelevant to Beijing, much less the entire world, to having to evacuate the country.

LD: Wow. Well, and then you started Princeton virtually?

GC: I did.

LD: Wow. What was that like?

GC: I think it was definitely unfortunate that we didn’t get to start our Princeton experience in the community of Princetonians, but I think there were also pros to having that kind of transition to Princeton because, at least for me, I was able to transition to the academics of Princeton before really getting involved in student groups and student life on campus. So it was honestly a process of easing into Princeton that I think historically other classes haven’t necessarily had.

LD: Now you’re going to go back to Beijing for your master’s program. That’s coming full circle, going back to finish what you started. Oh, that’s great. What do you plan to study there? You have, you said, master’s, public policy?

GC: Yes. Master’s in global affairs and it’s also a leadership — so I’m not sure how to the extent to which I clarified this earlier, but it’s through the Schwarzman Scholars program, which is also a leadership-focused program. So part of my coursework will be in various China-related studies, and part of it will also be in various leadership-related courses.

LD: So you don’t have to have an answer to this by the way, but do you know where you want to go from there? Feel free to say no. You’re young, you have time.

GC: I’m considering different options right now. I’m definitely interested in academia, but I’m also interested in law, so I’m not sure where I’ll land yet, but those are some of my interests at least.

LD: What advice would you give to students who are heading here next year? Just about how to start at Princeton, how to have their Princeton experience. You got any words of wisdom as someone who clearly did it very successfully?

GC: I think don’t be afraid to pursue what you love while you’re here because it really is a unique four years of your life where you can really explore topics that you’re passionate about and that are deeply interesting to you. And given my family background, my parents, especially my dad wasn’t necessarily thrilled that I became an anthropology major. He wanted me to be pre-med, something that I think a lot of students can relate to, but I decided to go for it and keep studying anthropology. And now, he’s very supportive and happy. So I think that just giving yourself the luxury, if you can, of studying what you love and what you’re truly interested in while you’re here is really important.

LD: Nice. And is there anything else you’d like to say? That goes through about all of my questions. Is there anything you’d like to say or anything you’d like people to know?

GC: I don’t think there’s anything else. If anything, it’s just that I’ve really enjoyed my time at Princeton, and I’m really deeply thankful to the University and to everyone who’s made this experience possible.

LD: Well, thank you so much for taking the time to talk to me today. I really appreciate it, and good luck with everything.

GC: Thank you very much.

PAWcast is a monthly interview podcast produced by the Princeton Alumni Weekly. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, and SoundCloud. You can read transcripts of every episode on our website, paw.princeton.edu. Music for this podcast is licensed from Universal Production Music.

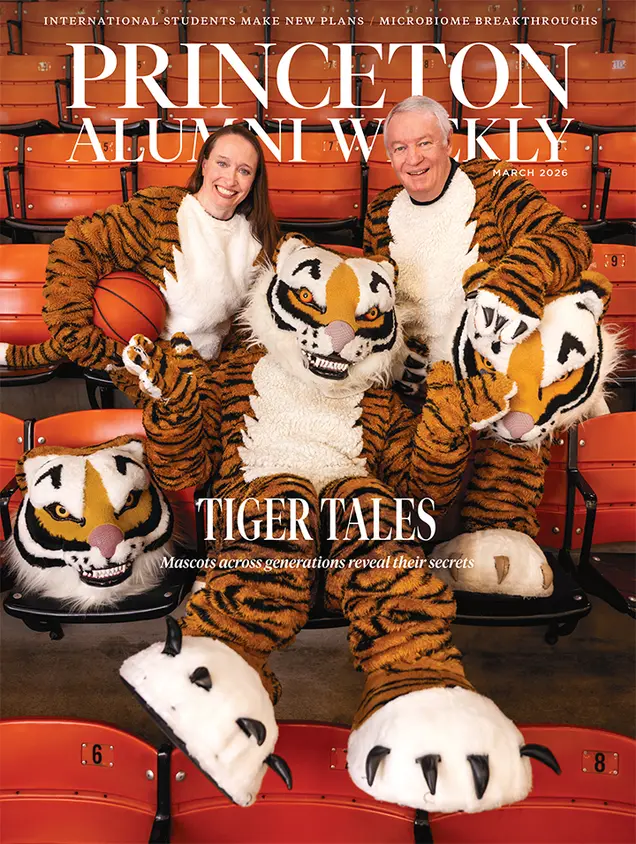

Paw in print

March 2026

Mascots across generations; biome breakthroughs; international students make new plans.

No responses yet