Podcaster Milano Buckley ’02 on Parenting and an Unusual Childhood

‘Parenting is the ultimate and the great equalizer. And we all get stuck in these moments where we don’t have maps, we don’t have answers’

On this episode of the PAWcast, Milano Buckley ’02 tells her story of growing up with an extraordinary but troubled mother, and how becoming a mother herself threw into sharp relief how the ways we were raised affect our own parenting. After much reflection and research, she’s now sharing what she learned in a podcast aimed at the wonderful messiness of parenting, called Bare Naked Moms.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT

In an article she published about a year ago, Milano Buckley from Princeton’s Class of 2002, explained that when she was born, her mother, a single schizophrenic mother, was homeless. She was living in her car, and she kept baby Milano in a basket in the backseat. What followed was an exceptionally unusual childhood that remarkably led Milano to the Lawrenceville School, and then later to Princeton. When Milano became a mother herself, she figured parenting would be a cinch compared to what she’d experienced in her own life. It turned out to be much, much harder.

And now she’s telling people. With a friend, Milano has started a podcast called Bare Naked Moms that seeks to tackle the challenges of parenting through honest conversations. Milano agreed to come on the PAWcast and talk about the work that she’s been doing, and the part that Princeton played in her journey.

Liz Daugherty: So Milano, thank you so much for being here today. I think you’re just the most interesting person, and I’m so excited to hear more of your story.

Milano Buckley ’02: Well, thank you for having me, and thank you for those kind words.

LD: So have you always been this open about your experiences growing up? In the last year you published this article and you’re talking about it on the podcast, which actually has an “Ask Milano Anything” segment.

MB: It does.

LD: Which I love.

MB: You do? Because we’re actually thinking about dispensing with that, so that’s good to know that you love it.

LD: I love it.

MB: OK.

LD: Because I think it’s so interesting.

MB: Yeah.

LD: So have you always talked about it like this or is telling your story something that you’ve come around to and why now?

MB: Great question. No. The short answer is I definitely have not always talked about it. And I definitely have come around I would say in the last, not even since becoming a mom. I would say much later, in last four or five years, I have really settled in to the story, and formed a new relationship with it, if that makes sense.

When I was growing up, I would say that I did what I needed to do. I just maneuvered every situation as it came. When I went to school, I definitely didn’t want to talk about my mother or to have anybody know about my situation. I wanted to be as normal as possible. I wanted to fit in. It couldn’t be a secret because she was around, so I had to just handle it as things came. So it definitely wasn’t a secret. But every waking minute I had, I spent trying to participate in trends and fads and social groups, and just try and at least look as normal as possible, even though I knew, of course, that I wasn’t and my circumstances weren’t.

When I went to Lawrenceville, it was all about fitting in and wearing the things that other people were wearing and minimizing the things that separated me, for sure. But again, my mother would show up. And so I had to be really quick on my feet. And I was really facile with crisis control and damage control and spinning and branding and storytelling in a way that this would make sense, and this was digestible to other people as well as to myself.

LD: What do you think changed? You said it was around COVID. COVID changed everything.

MB: I know, COVID changed everything. I think part of it was coincidence. I think it was just the intersection of how old I was and where I was in my mom journey. And COVID was so triggering for me. It was so triggering for so many people. But for me, I had very physiological, visceral reactions to this idea that this thing had happened that we were supposed to be protected from, and we couldn’t trust anyone who was telling us anything about this.

None of the adults in the room were in control. And they were making it seem like they were, but they weren’t. And we couldn’t trust any of the adults, any of the captains who were supposed to have the maps and the GPS and to steer us out of this mess, didn’t have maps. And that was really, really triggering for me that we were supposed to trust these authority figures, who absolutely little by little revealed that they could not be trusted and that actually the emperor had no clothes, that they didn’t really know what was going on. That was very, very uncomfortable for me. It totally brought back so much of my childhood that of course I didn’t know. I didn’t make all those connections in real time. But that’s what was going on.

But I don’t think that’s the only reason. I think that it’s so much more exhausting to not talk about it. And I think I was just tired. And I always thought that the actual stuff made me tired. Like, oh my gosh. By the time I was in my 20s, I remember feeling like I’m so exhausted by everything that’s happened up until now, I don’t know how I’m going to do things like survive anything else. Please Lord, let me have my health until I die, because I don’t know how I’m going to survive anything else. I’m just so exhausted. But the exhaustion actually isn’t from the survival, I think it’s from not processing the trauma and holding it and not owning it. Holding it, but not owning it, if that makes any sense.

So I think the real thing that made talking about it appealing in the end was these things that kept popping up in my parenting. These triggers that I kept tripping over. It wasn’t sustainable. I didn’t like it. I could tell that these were really big things that needed to be addressed. And if they weren’t addressed, it was just going to be worse for everybody. So it was unavoidable. So I think that’s what it made me start talking about it. And I feel like once I did, it was a relief and very freeing and healing. I kept doing it and here we are.

LD: Now you’ve touched on a few bits of your story, but for anyone who doesn’t know it or hasn’t read the article, do you want to give the CliffsNotes version?

MB: Yeah. Sure.

LD: I hate to say just sum up your whole incredibly dramatic-

MB: 45 years.

LD: Just give me a minute. Can you just sum the whole thing up?

MB: Absolutely. I’ll do my best. So I was born in 1979 in Brunswick, Maine. And my mother was, we now know of course, but when I was 12, she was officially diagnosed as bipolar with schizophrenic tendencies. But up until the age of 12 and long after, but up until the age of 12 there was so much craziness that filled my childhood. And when I was actually born, she didn’t have a home. She was living in her car. We were homeless.

And she found her way or our way down to New York City from Maine. And she got a job at Barnard College. She was an administrative assistant in the dean’s office. She worked for the dean of studies, and that got us an apartment. Like a staff apartment. A Columbia housing staff, apartment. Faculty apartment. And so we lived in that apartment and she actually rented rooms out to students at the theological seminary, for example, or Manhattan School of Music. It was a grand central station of lots of young people and transient students passing through from year to year.

When I was a baby, this kicked off this pattern of other people taking care of me and taking me into their homes. But when I was a baby, she put up a flyer in some community center on campus. And somebody around the corner, Asay DeMaio, who is from Ghana, she was a teenager, and she responded. So I was a little baby and she took me home and her mother, Dorcas, came home and she had four siblings, one sister and three brothers. And her mother came home and Asay had this little white baby with her. And her mom said, “What are you doing? Who is this?” And she said, “Oh, I responded to an ad.” So Dorcas investigated and met my mother, whose name was Cat.

And she determined that it was God’s will that this baby entered their lives, and that it was her purpose per God and his suggestion that she accept this baby into her life and care for it. So the first seven years of my life, I have photos from both universes. Me with my mother, me with Dorcas as my mother, in both homes. They were around the corner from each other. And I looked completely different. I had completely different facial expressions, completely different auras and energies about me within these photos of that my mother took in her world and then the photos of my African family. It’s wild.

Anyway, so she took me back. There was a big dramatic moment where after giving them power almost power of attorney. Custody, I guess. She reversed that and said, “I want my daughter back.” And it was very dramatic. I didn’t see them again. I think it was like the summer going into second grade. Didn’t see them again for 30 years. Facebook brought us back together.

So then I lived with my mother for a couple of years, and then I lived with my third grade teacher for many years, who’s now my mother. My biological mother Kat passed away. But Kitty, if you can stand it. Her name is Kitty. Kat and Kitty. My third grade teacher, Kitty Graves remained in my life this whole time. And she’s now Grandma Kitty to my kids. She lives down the street from us in Westchester. She was the next person who took care of me. And then my aunt and uncle took care of me. And then before I went to Lawrenceville, I went to a private school in the city and the principal, the head of school there, and her husband stepped in as other caretakers. He went to Lawrenceville and he went to Princeton, Larry, and so he was really instrumental in that path for me.

That was a pretty good job of a wrap up. Don’t you think? It wasn’t a minute.

LD: It’s just wild. It’s just so wild. And I can’t even imagine what was happening in between all of those bigger picture things, like the moments in the day to day.

So you went to the Lawrenceville School, amazing. I live close to it. It’s an amazing place. I’d like to ask, how did you end up at Princeton? And what was your experience here like? Because, and I’m going to preface this by saying that I’m particularly curious about this because we hear so often from alumni who say they feel like they didn’t belong at Princeton because they felt different, or they had what they think was an unusual background. And this imposter syndrome actually strikes me as so universal. If everyone has imposter syndrome, no one has imposter syndrome.

MB: No one is an imposter.

LD: Right, no one is an imposter. So I’m very curious. You had this crazy childhood, what was it like to arrive at Princeton and then to be a Princeton student?

MB: I was just all about faking it until, faking it until you make it. And so I definitely felt like an imposter. But I think I felt like an imposter. And fairness to Princeton, I think I felt like an imposter in most scenarios.

How I got to Princeton, Larry Leighton, who was the husband of the Calhoun head of school, Mariana Leighton, is one of many people who, who saw me, met me, talked to me, knew my story, and thought, this is a really great story. I sang for my supper. I had a spark and a sparkle, and I knew how to use my story. And I don’t mean in a bad way, but in a hustling way. I was a hustler. “Yes, this is my story. You can help me. You can help me. You can help me. Who can help me? You can help me. OK. Let’s do it. Help me.” That was the survivor, that was the inner survivor of me or outer all survivor, all survivor. So I really had that.

And he said, “I think that you would be really great at Lawrenceville and I’ll do whatever I can to help you.” And so he was just a real connector. That’s who he was. He just was a real networker and said, “I think you should talk to this person, you should talk to this person.” I was a public speaker at Lawrenceville. I won awards for public speaking. And I thought, you know what? Well, other people, athletes, they take footage of their plays in a football game or a lacrosse game. They have someone video them. I’m going to have someone video me do public speaking. And so I did. And so I sent my tapes around.

But he did introduce me. He introduced me to Fred Hargadon, who was the dean of admissions. I don’t know how he knew Fred Hargadon, but he did. And Fred took the meeting and he said, “Well, tell me about you.” I said, “Oh,” And by the way, I just didn’t have any dream of coming here. It’s not like I was a bad, bad student at all. I was a perfectly good student, but you know what it is to get into Princeton. Even back then.

So I had this meeting with Fred Hargadon before my senior year, and I said, “Well, this is this and that is that, and this is,” basically what I’ve told you and maybe some more. And he said, “Well, listen, here’s the Princeton application. Why don’t you look it over? Tell me what you think.” And I said, “Please. I can’t get into this place.” And he was like, “Well, yeah, maybe not. Maybe, you know.” And so I told Larry what had happened in the meeting. He said, “Well, I think that you should definitely apply.” And so I did. I applied. I’m a writer, I can write. And I’m a speaker, I can speak. And so here we are. Here we are.

I got in. And so I definitely felt like an imposter. And I think about this a lot with regard to the DEI discussions and affirmative action. I think about what someone feels like when a door has been opened for them, but not in a traditional way.

LD: Let’s fast-forward to parenting, because this is the subject of your podcast. This was a big part of your journey. What was it like for you when you started parenting? I know I came to it with baggage that I didn’t even know I had, so I can’t even imagine what this happened for you. What was it like? What was it like becoming a parent?

MB: So I always wanted to become a parent because, it was just never a question. That was always just the end goal. And everything else that happened was on the way to that. I just thought, I just need to get to that. It was like the finish line and also the entrance into Shangri-La. When I get to be that, then I can hang my gloves up and really settle into this life and get comfortable.

And it’s so ironic because it wasn’t immediately uncomfortable at all. I was pretty good at that beginning stuff. The perfunctory diaper changes. As long as there was a system and you could map it out. I think all the mappable stuff was, it took a little bit to map it out but once you did that, there was enough resources online and with outsourcing to baby nurses and arming up with expert books and workshops and coaches and all these things. So you can pretty much find any friend to phone, whether it’s about lactation or diapers or feeding or sleeping or why your baby’s crying. So that was navigable, fairly.

But then my baby boy, I have three now. So my firstborn, Buzz just started to not do things according to my plan. He had a personality and he was stubborn. I look back and I just didn’t know anything about what I was doing as a parent. I didn’t know anything about humans and development and what was quote-unquote normal, what wasn’t. I didn’t have any siblings. I didn’t have any modeling in my own childhood. I was just bouncing around from one place to one place. I guess the best modeling I had was with my aunt and uncle, my mother’s sister and her husband. And they had kids and they were great parents. It was a real home, two parents, three meals a day, a lot of structure and a lot of warmth and nurturing and care. Dependability. So I had a little bit of modeling there, but beyond that, I just didn’t know, oh, it’s totally normal when your toddler throws a temper tantrum. Or kids get really tired around this time, so not a good idea to schedule a haircut at that time. All that anticipation and just the natural feeling. Anyway, I didn’t have any of that.

And I think that when you have trauma in your childhood or when you’re trying to use parenting, unwittingly use it as a balm for that imperfection, I think that you set up some real rigid expectations. And when the reality goes beyond those boundaries and is messier, I think that it’s really triggering of the trauma. It’s like, “No, no, no, no, no, no, no. That’s not supposed to be happening. No. Go back in your box. Go back, go back. This isn’t my perfect vision.” And that’s all the more upsetting, because not only is there is some mess that’s happening, but it’s mess that shouldn’t and can’t happen. It can’t happen because, no. Because this is supposed to be everything that that wasn’t.

And so, yeah, when that started happening, oh my gosh. I would have these moments where I would just be tripping into another dimension, which I now can recognize as PTSD, where I’m like, “You’re not listening to me. Why aren’t you listening to me? We just had this conversation about you putting your” — I’m just making this up — “you putting your clothes on because we have to get out because we have to be there because we’re going to be late if we’re not.” There was just such an emphasis on doing everything the exact right way. And when people weren’t listening to me, which by the way is no one, no kid listens to their parents, was like I turned into that little girl who wasn’t being listened to when she said, “I’m really tired. I just want to go to bed. I don’t want to go to that art show. No. I don’t want to see Tibetan bowl ringing. I have homework to do. No, I’m really hungry. It’s like 9:00 and I haven’t had dinner.” Like, “Where did you go? Where did you go? Are you here? Where are you? I see you, but where are you?”

So it brought all of that stuff back. I would be out of control. And I thought, oh my gosh, why are these kids pushing my buttons? Why are these kids pushing my buttons? And I just really recently happened upon this wisdom that people can’t push your buttons if you don’t have buttons. Isn’t that wild? It’s like so simple and so amazing.

LD: Who doesn’t have buttons, though?

MB: I know. Who doesn’t have buttons? We all have to when we’re like, it’s like, “You’re not doing this or you’re not doing that, or oh, my God, you are really going to get it.” It’s like, what is that? That’s not about them, that’s about you. So I guess I started to really say, OK, I’ve got to figure out, I’m looking at this all the wrong way. It’s not about them. They’re being who they should be. This is about me. And then I started doing all this really intensive work about the past and what were these triggers and why were they there.

LD: I think that’s an extreme version of something that a lot of people go through.

MB: I think so. Right.

LD: You know what I mean? It’s interesting to hear you say it because I think a lot of people will connect with that sentiment. A lot.

MB: That’s really funny you say, because for the past five years, I’ve been in and out of trauma therapy, and I recently revisited my therapist and she said, “You know what?” Because I often do this. I’m like, “Well, this is what happened and this is how I responded.” And I’ll be like, “What would someone without my triggers, what would they do in that situation?” And she finally said, “You know what, Milano, I want to tell you something. You’ve graduated. You are now just a normal, messy human with messy scenarios and messy relationships. All of this is something that normal people would have a hard time with, so you’ve graduated to normal.”

LD: Oh, no. And you said, “I thought it would be better than this.”

MB: Yeah. Totally.

LD: Oh, dear. So let’s talk about the podcast. So out of all of this parenting, you’ve decided to do a whole podcast about parenting. About which obviously you’ve learned quite a bit. The first season is out, it premiered in the fall, and that name Bare Naked Moms, so funny. Is a reference to being real. About parenting, which reveals so much of who we are. How did that come about and how did your own experiences, all of this being parented and parenting play a role in that?

MB: Because I obviously feel so vulnerable in the parenting space, having not had the modeling, having had so much trauma, I spent so much time looking outward for counsel. Whether it was baby nurses or books or listening to podcasts. And so I ended up in a workshop that my kid’s preschool was, and it was moderated by a woman, and it was a real program. What we did was we went into that book, How to Talk So Kids Will Listen & How to Listen, So Kids Will Talk, it’s the best. It’s the bible of modern parenting. Even though it’s 40 years old, it’s so on point still.

So I went into this workshop. There were about eight other women. And what’s so cool about a workshop like that and having it be so small — we met once a week, we did one chapter at a time, we did homework, we shared — is that everyone who goes into that room is vulnerable and they’re owning it. They’re like, “Yeah. This whole thing, being a mom that’s supposed to come so naturally, well, it doesn’t for me and I’m kind of lost.” And when you have nine women who are in that space of vulnerability and not trying to one-up each other and not trying to compete and just saying, “Can you help me? Can you help me? What are you doing about this?” It’s really like special and powerful. And so I went into that and my co-host, Alanna, was also in that group. We did this, and then it was so powerful and soothing and comforting and empowering for us that we continued it with the sequel book. And then we’re like, “Well, we can’t stop now.” And so then we would do month by month, just refreshers.

Anyway, so that was 2019. And then during COVID, I was just devouring podcasts. And I had so many ideas about what I was telling you about the authorities who basically were totally asleep at the switch and just trying to make everyone think that they knew what was going on but didn’t. Anyway, so I’m mouthing off all the time and people are like, “Milano, you should do a podcast.” I’m like, “I don’t want to do a podcast. Oh God, no. I don’t want to do that.” It’s scary and it’s alone and I have to get equipment and digital. No. It’s all daunting. And so my friend Alanna, who was also in that workshop and now the co-host of Bare Naked Moms had a background in news production. She worked at Inside Edition. I said, “What if we did this?”

And so that was how it was born. The idea is that look like Alanna was also a single child, an only child, grew up in New York City, but had a completely different background than I did. She had two doting parents. They lived on Park Avenue, she went to Sacred Heart for 13 years. Just totally structured. So full of dependability and security and resources that we thought, this is wild. This is so fascinating that two people can have such wildly different backgrounds and still be so insecure in themselves as parents.

That’s where the idea came from. Is that whether you’re poor, you’re rich, you’re educated, you’re not educated, you’re a superstar with bodyguards or soccer carpoolers like us, parenting is the ultimate and the great equalizer. And we all get stuck in these moments where we don’t have maps, we don’t have answers. No matter how much guidance or no guidance we had, we’re vulnerable, we’re bare, and we’re naked and we’re caught off guard like deer in headlights. And then the balm, the antidote to feeling like a deer in headlights is to know that other people feel the same and to connect through the confusion.

LD: Do you have any advice for your classmates who are parenting their tiger cubs out there in the trenches trying to figure this whole thing out?

MB: Kind of. And it feels weird for me to be the one giving advice, so I don’t know if I would frame it that way. But I do have some insights and observations.

I’m trying to ask myself about big things and small things every single day. How much does this matter? And I try and follow it to the end point of like, OK. The decision tree of like, OK, so this will happen, so this will happen. OK. If that happens, then that’ll happen. And I just sit with it. Everyone says be calm, be calm, be calm. And that’s so true. But I think what being calm really means is reflect and respond. Don’t react. Stop the whack-a-mole and just sit still for a second. And nothing crazy is going to happen if you sit still.

I would say that. I would say the other thing is, in anything that I’ve ever read, and I’ve read a lot now. Anyone I’ve ever talked to you, whether you’re talking about resilience, which we are talking about this season with a wonderful woman. Whether you’re talking about resilience, whether you’re talking about success as a human, resilience, self-esteem, puberty, the number one thing is to stay connected with your kid. Is just stay connected. It doesn’t mean that there aren’t going to be arguments. It doesn’t mean that they’re not going to be totally pissed off with you. It doesn’t mean any of that. It doesn’t mean there’s not going to be a mess. But it’s like when there is, find your way back and repair. Make repairs.

You have a hose, right? It doesn’t mean that there’s not going to be cracks in the hose and that water’s not going to spout out that way and that way and all the way through. But duct tape it. And when it happens, duct tape, duct tape. And just maintain that connection because that is the thing that is going to keep them talking to you and keep them trusting you. In the bad. It’s not going to prevent the bad. It’s just when there is bad, when there is scary, when there is uncertain, them knowing that they’re connected to you is the most foundational, the most important thing that will lead to how they feel about themselves and how they walk through this world. Isn’t that wild?

LD: I think that’s great advice.

MB: It’s so simple. It’s so simple. And yet pretty hard. It’s pretty hard to constantly remember that. It doesn’t have to do with what travel club they get on. It doesn’t have to do with what school they’re accepted to, what grades they get, what homework they did or didn’t do. It’s that.

LD: That’s incredibly helpful because you can get so in the weeds of every little thing that’s going on. Am I doing this right? Are they going to turn out to be a good person? Am I making a mistake? That’s like a north star.

MB: It’s a north star.

LD: It is.

MB: For sure.

LD: So we’ve actually hit the end of my questions. Is there anything else you’d like to talk about or anything you wanted to bring up?

MB: Well, I don’t know how relevant this is to the pod, but being here makes me think about my time here with this crazy set of circumstances that I inherited. And my mother, if you’re wondering and you want a visual, she very much looked like a bag lady that you might pass in a public park in the city, or anywhere in public transportation. She looked like a bag lady. She literally had many, many, many, many bags with her at all times of her belongings and everything. She would come to these places, she would come to Lawrenceville, she would come to Princeton, which was so like trespassing for me because I was trying to build this new, I don’t know. These new environments for myself. These new communities for myself that felt good. I was trying to thrive and so much of my thriving and surviving had to do with not talking about that and not wearing it.

And so Lawrenceville was so amazing to me in that they said, “Whatever you want to do is what we’ll do.” And so she wasn’t allowed on the campus, but she would like go to the pizzeria across the street and she would talk to people and say, “Do you know Milano? Here, will you give this to her? I’m her mother.” And I’d be like, “Oh, man. Damn.” I would roll this ball up the hill and it’d roll back down. No. But it was like, it just felt so defeating.

So when I went to Princeton, she did the same thing. She actually didn’t know I was going to Princeton. And it was my birthday. Our birthdays are two days apart, Oct. 9 and Oct. 11. And I had told her I was going to Southern Methodist University. That’s where I was going. Because if she was going to get ahold of me that she would go to Texas and not where I actually was.

And then she went into a depression and I didn’t hear from her for a really long time. Around my graduation and then over the summer and then into fall I just really didn’t hear from her. Even, I was worried because she would always find me. And it was my birthday and Kitty had come to take me out and we were just turning the corner where Winberries is, and I hear from the car — she had this very, very husky mythical voice — she goes, “Happy birthday.” And I looked down and it’s her. And she had just come out of the hospital with her boyfriend, Fred, and he was in the post office and she was totally medicated and so very lucid and sober.

And it was like the most amazing meeting because I was a freshman at the time. And she looked at me and she said, “You go here, don’t you?” And I just was literally just in tears, almost. I’m surprised I could even stand up. I don’t think I stood for very long because I knelt to be with her. She was in the car and the window was open. And I said, “I do.” And she’s like, “I’m so proud of you.” And we talked and she’s like, “I’d really like to see you.” And I was like, “OK. Well, let’s see. Whatever. Let’s keep talking.” And it was very beautiful. I feel like that’s the last time that I really had like a lucid connecting conversation with her where I recognized her and we were really communicating on the same wavelength.

Anyway, after that, she soon became manic. And the University was so amazing to me. When she became manic, she would leave these wild voicemails and do her old things and she would, anyway. She would go to all the stores in town and have them call me. I had to get a restraining order from her. First temporary and then permanent. And the University was so amazing. I went to Dean Hargadon who connected me to the dean of students, and then I said, “I need her to not be allowed on campus.” They did that. I said, “Next year I really need to live not in the perimeter. I want to live farther down.” They said, “No problem.” All of the security, the campus patrol were so kind and gracious and compassionate to everyone. Every time they spoke to her and said, “Now, you know Ms. Miodini, you can’t come on the campus. You know that.” They were just so gentle and compassionate to all the players involved.

And every time I saw them, they would wave to me and go, “How are you doing?” And every time she came, I would call them and I would say, “I saw her.” They were like, “We’re on it. Don’t worry about it. We’ve got this. We’ve got you.” It felt like a really safe place and they made great efforts to make me feel safe here. And so I’ve always been incredibly grateful and just aware of that.

LD: That’s really nice to hear. Tough to hear that you went through that, but nice to hear that it worked and that you were able to feel safe and secure and stable and at home when you were here.

MB: There were so many people throughout my life who provided that, which is why I think I’m reasonably OK as a 45-year-old woman with three children and a husband and a house. I think that they are definitely some of those people.

LD: This is what I’m saying. You dig a little bit and you find the Princeton alumni have these stories. So it’s a privilege to hear yours.

MB: Thank you. It’s a privilege to tell you.

LD: Thank you so much for coming on. I really appreciate it.

MB: Thanks for having me. It’s so great to be here.

LD: OK. And if you’re just listening to this, make sure that you go to paw.princeton.edu. In the transcript for this we’re going to link to the story, the article that Milano wrote and to her podcast, so you can go check that out as well.

PAWcast is a monthly interview podcast produced by the Princeton Alumni Weekly. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and SoundCloud. You can read transcripts of every episode on our website, paw.princeton.edu. Music for this podcast is licensed from Universal Production Music.

Paw in print

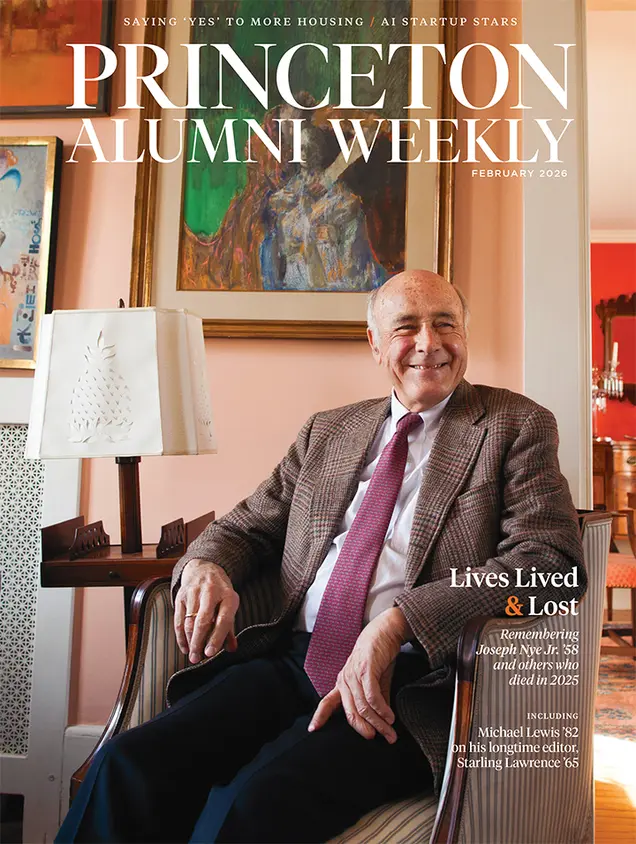

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

No responses yet