Q&A: Author Jacob Sager Weinstein ’94 on Writing for Young Readers

PAW’s Q&A Podcast — May 2018

It took Jacob Sager Weinstein ’94 about a decade to sell his first book for young readers, Hyacinth and the Secrets Beneath (Random House Books for Young Readers), a fantasy and adventure story about an American girl navigating the magical underground rivers of London. With the second book in the trilogy, Hyacinth and the Stone Thief, coming out this month, we spoke with Weinstein about his persistence in creating the Hyacinth series and the challenges and joys of writing for children — as it turns out, 10-year-olds might have been his natural audience all along. Sager Weinstein also explains how he handles writer’s block and the role that Triangle Club and Quipfire! played in teaching him how to write with a specific audience in mind.

This is part of a monthly series of interviews with alumni, faculty, and students. PAW podcasts are also available on iTunes — click here to subscribe.

TRANSCRIPT

Brett Tomlinson: I’m Brett Tomlinson, and this is the Princeton Alumni Weekly’s Q&A podcast. This is our 11th episode, and so far we’ve featured several authors, alumni who’ve written about immigration, about math, about philosophy and the midlife crisis. Jacob Sager Weinstein is the first in our series who’s written about a giant pig in a bathing suit who lives in the secret underground rivers of London.

Jacob, a 1994 Princeton grad, is an author of children’s books, including Hyacinth and the Secrets Beneath, an adventure story that was released last year, and came to paperback in April. The second book in the series, Hyacinth and the Stone Thief, is due out May 15, and he is on the line with us from London. Jacob, thanks for joining me.

Jacob Sager Weinstein: My pleasure. Great to talk to you.

BT: So to begin, could you tell me a bit about your career path? I know some bits and pieces from your Princeton days, that you were a founding member of Quipfire!, the improv comedy troupe, and you wrote for the Triangle Club as well, majored in English. Did those experiences shape your route after college?

JSW: Yeah, they did. I would say, and I’m going to wade into controversy right off the bat, of those things, the one that was maybe the least practical use in becoming a writer was the English degree, just because the way you approach writing from a critical perspective is, I think, different from the way you approach it when you’re writing the piece. But I found that being in Quipfire!, and writing for Triangle, just the experience of writing something, or improvising something, and seeing how an audience reacts, gives you — it’s just an amazing lesson in what is effective writing, and what is not.

BT: And what did you want to do after college? I mean, did you have a sense of what types of things you wanted to write?

JSW: Well, I did know I wanted to be a writer. Oh, I should also mention that in addition to majoring in English, I got a certificate in the creative writing program, and that, I found, was extremely useful. I studied with Toni Morrison, Mary Morris, Russell Banks, and that sort of, that taught me a huge amount about how to think like a writer. I wasn’t entirely sure what kind of writing I wanted to do, I just knew I wanted to be a writer. So, after I graduated, I tried some different things. I spent a year working for Washingtonian magazine, in Washington, D.C., and concluded from that, that I did not want to be a journalist. It’s just much more fun to make stuff up than to research it. And they tend to frown on making stuff up in journalism.

So then, I thought I would be a TV sitcom writer. I moved to Los Angeles, I wrote a couple of spec scripts for various sitcoms with my fellow Quipfire! and Triangle alum, Rob Kutner, class of ’94. Eventually, I decided I did not want to be a sitcom writer. I did end up being a staff writer on a comedy variety show on HBO called Dennis Miller Live. I thought for a long time that what I wanted to do was screenplays and movies. And did that, and made some headway, and sold some scripts that never got made. And sort of eventually, around the time my kids were born is when I finally decided that children’s writing was what I wanted to pursue. So it’s been sort of a long and roundabout path.

BT: And there is, I imagine, quite a different in tone when you’re writing a joke for Dennis Miller, or writing a screenplay, or writing a chapter book for a 9 or 10-year-old. What was appealing to you about the idea of writing children’s books, and what were sort of the challenges of breaking into it?

JSW: Well, it’s interesting. And it’s certainly, for those who saw the Dennis Miller Show, it was very adult, there was a lot of swear words, there was sexual content, but actually, I was always — that didn’t come naturally to me. And actually, I had to make an effort to sort of write in that more adult voice. So with hindsight, I maybe was destined for children’s books all along. I think that there’s obviously a difference in the kinds of things you can cover.

But you know, I skipped over an important step. Which is, I wrote three books with Matthew David Brozik [’94], who is one of the founders of Quipfire!, that we thought were for adults or maybe very sophisticated college students, and I kept meeting 10-year-olds who liked them. And so I sort of, I sometimes describe myself as an accidental children’s book writer, and what I concluded from that is that I could write at the very top of my intelligence and ability, and it would be just about right for a 10-year-old. And I don’t know if that says something —

BT: Those books were the, uh, I think there was one about a guide for pirates, and one about superheroes or something like that?

JSW: That is exactly right. It was The Government Manual for New Wizards, The Government Manual for New Pirates, and The Government Manual for New Superheroes. And the fact that I thought those were grownup books, again, may tell you something about how I think and how my interests are.

BT: So, you had the, kind of the sense of the audience maybe inadvertently, you had some experience writing, but it’s not the type of thing that you can just kind of break into easily. I gather it’s a difficult process to find a publisher, and to kind of get that first break. What was it like for you? I gather it took some time.

JSW: Yeah, it was a very hard process. And I have to admit, I was rather arrogant, as I think a lot of writers are when they first contemplate children’s books. So the books that I wrote with Matthew, I think, were on the order of 20,000 words. You know, a picture book is on the order of 500 words. So I sort of figured, “Oh I could write a picture book a week!” But it turned out, especially with picture books, but also with middle grade novels, which Hyacinth is, that the fewer words you have to work with, the more each word counts.

So, I started writing — I decided I’d start seriously pursuing children’s books around 2008, 2007. And my first children’s book just came out last year. So it was sort of, almost a decade really, of writing and rewriting, and I was working on Hyacinth sort of simultaneously with various picture books. And I’d work on a picture book for a while, I’d put it aside, I’d work on Hyacinth, I’d put that aside. I’d come back. I did, just constantly had to rewrite Hyacinth. And would send it off, and get rejected, and try to learn from the rejection, and rewrite it again. It was a very long and frequently discouraging process.

BT: And what kept you going through all that rejection and rewriting, and that process?

JSW: Gosh, I think at the beginning, it was the arrogant belief that it was going to be a fairly easy and brief process. And then as it kept going, I had just become so attached to this world I had created. I should maybe explain that Hyacinth, and I think you mentioned this, it’s set in sort of a magical version of London, the conceit of it is that the — everything that the history books tell you about London’s history is a cover story for this secret magical history that has existed. And I had worked out an extensive backstory, and the rules of this world, and centuries of history, and I just, it was I guess the Vietnam syndrome, in literary form, where you just get committed to something, you’ve put so much effort into it, you really, it just drives you forward to keep going.

But I will be honest that towards the end, I had really come to feel that I probably was not going to get published. And that all this effort was going to be for naught, and I was trying to figure out what else I could do with my life, and I literally couldn’t think of anything else I was especially qualified for. And it was, I’d say about two or three months into that real despair, that I got an agent for the book, and very quickly sold it. So, if I figured out something I was qualified for, I might have switched over to it sooner.

BT: In the current landscape for authors, is there pressure to write within certain boundaries, certain genres, or is it a space that rewards originality, in your experience?

JSW: I think whether you get that pressure — I think that pressure is often self-inflicted. And I would encourage anybody who’s listening to this, who’s interested in writing, to resist putting that pressure on themselves as much as possible.

You know, thinking about it, something else that kept me going on this book was the feeling that this was a book that only I could write. I’ve always been fascinated by quirky bits of history, I’ve always been fascinated by fantasy stories, and by conspiracy theories, and I’ve really loved the city of London. And so I feel like this book came out of a combination of things — obviously lots of people feel each of those individual things, but the specific recipe of that combination of things in that proportion was really me, and an expression of me. And I think had I been trying to write another Harry Potter, or another Percy Jackson, I don’t think it ever would have worked. I think, not only would I not have sold it, I’m not sure I would have had sort of the passion and the cussedness to keep going with it over the years that it took.

BT: And as I said at the top, you’re based in London, and it is a huge part of the first book, I’m not sure, is it — is the second one also set in London?

JSW: That’s right, absolutely. All three books in the trilogy are very London-centric.

BT: And what is it about London, the kind of quirks of it, that appeal to you? And do you think, you know, an English native would have had the same perception of the city, or well, not perception, but the same ability to kind of reimagine it as an American would?

JSW: I think you’ve put your finger on something, and I think that definitely the answer to that second question is no. That obviously, you can hear from my voice and my accent I am not a native Briton. My wife and I moved here just about 15 years ago. And I do think that if you grow up someplace, if you live there all your life, you take its oddities and quirks for granted. So there were a lot of things that I started noticing when I moved here, from little things like the way the faucets work here, to bigger things like just the extent of the history here.

I still remember shortly after we arrived, we went to a concert in a church, and they were doing renovations to the church, and there was just a big piece of lumber from somewhere in the church lying in the lobby of the church. And on it was a date that was 1725, I think. And I just remember thinking, this piece of wood is older than my country, and nobody is paying any attention to it. It’s just practically scrap. I mean I’m sure they were going to put it back, but there was no — nobody seemed impressed at this ancient piece of wood just sitting in the middle of the lobby. And as somebody who, I grew up in Washington, D.C., which is relatively historic. But you know, I spent seven years of my life in Los Angeles, where a historic building dates back to 1955. So, the vastness of the history here ends up being just this fantastic playing field, this fantastic thing to toy with, if you are making up a secret magical history.

BT: You mentioned you’re also a parent. Did your kids inspire the work that you’ve done?

JSW: They did, indirectly. I started really getting serious about it just at the time my daughter, my first child, was born. And you know, a lot of people gave us books as gifts for her, both picture books and kids books. And of course, when she was born, she wasn’t old enough to read those. But I would read them and I would remember just how much I loved all the books I read as a kid. And I was sort of struck anew by how incredibly well written and creative so many of them were. So, that was a huge inspiration in getting me to really focus on intentional children’s books.

In terms of them more directly inspiring me, I try to pay attention to the things that they like, and that are important to them in books they read. And that, I think, helps me keep my focus on what kids are passionate about reading. But an equal part of that, I think, is also my own memories of how I felt when I was a kid, and what I loved to read and hear about.

BT: Well, tell me a bit about that. I mean what was your reading story like? What authors did you like, what books did you reread, and what things made an impression on you, when you were a young reader?

JSW: Well the Narnia books were a huge favorite of mine. And actually, the Narnia books are responsible for me actually learning how to read. My mom used to read to me at bedtime, but one night, I don’t know if she was out, or sick, so my dad took over, and he thought it would be funny to put in like, my name instead of Aslan, and my brother’s name instead of Peter, and I had no idea what was happening in the book, because all the character names were wrong. And I realized you cannot depend on grownups to read to you, you have to do it for yourself. So that, I like, that sort of is what actually got me to buckle down and learn to read.

But, so yeah, so I loved the Narnia books. I mostly loved escapism. So the Narnia books, a fantasy author, Lloyd Alexander, who is not quite as appreciated as much as he should be, but he’s amazing. I loved Beverly Cleary, she was sort of the one realistic author I liked. I’m just blanking, there’s a wonderful, funny author who wrote Westerns a lot. Sid Fleischman. Sid Fleischman — Mr. Magic and Company, Me and the Man on the Moon-Eyed Horse — he was one of my favorites growing up.

BT: I’ve read a little bit about your method of writing, in which you mentioned creating a playlist for each project. Do you still do that?

JSW: I do, absolutely. And actually, one of the ways, when I was trying to figure out when I — so, when I sold Hyacinth, and the publisher would sort of send me a sheet for publicity purposes, asking me these same, when I started working on the book, various things, one of the ways I was able to track when I started on it was to look in iTunes and see when I added the first song to the playlist for this novel. And I should explain that the idea behind that is that for each project I work on, I create a specific playlist of songs that are either explicitly or thematically, or in some way related to the book. I listen to the same song each time I sit down for a writing session, and after that, it’s a randomized list. And it becomes this Pavlovian thing where as soon as I hear that song, I am immediately in the right frame of mind to start working on the book. The downside, of course, is that it then ruins that song for me forever, that I can never listen to it without feeling guilty that I’m not working on the book.

BT: Well you can always turn to the hardcover copy and say, “OK, that one’s done, I can re-listen to that song.”

JSW: Yes. Absolutely.

BT: What’s on your playlist now, and what’s the corresponding project?

JSW: I just finished working on a book for younger children, and I’m going to be a bit vague about it, because I just sent it off to my agent, and I don’t know if anything will happen with it. But it’s sort of a science fiction-y, sort of a goofy science fiction-y story. So, The Incredibles soundtrack is on there, because that’s great sort of action-y, science fiction-y music. There are — it’s about a robot, so there’s a bunch of robot theme songs, there’s a great They Might Be Giants song, “The Robot Parade,” that’s on there. And for Hyacinth and the Secrets Beneath, that one was a huge amount of mostly London themes, music, as you’d expect.

BT: And when you’re writing, do you have any tricks or tips, or things that kind of help you break through when you hit a rough patch, or kind of, I don’t want to use the B-word, but when you’re not quite feeling the flow of the piece?

JSW: So, I would say there are two things. And one of them is sort of ironic, given that I stopped doing journalism because I didn’t want to do research. But it turns out that research is really useful in fiction as well. So for something like Hyacinth, because it was so much based on this idea of a secret magical history, I was able to just take a lot of London’s actual history, and just give it these little twists to make it more magical. So, I have, God knows how many megabytes of stored research. I read huge — I’m sitting in my office right now, and I’m looking over at my shelf of London history books, and I’ve got multiple shelves sort of bulging with books about London history. And as I’d read them, anything that struck me as weird or contradictory, or mysterious, I would make a note of, and eventually try to work that into the story. So clearly, that’s less useful if you aren’t writing this specific kind of book. But I would say almost anything you are writing, you probably can deepen the book, and inspire yourself, by researching the reality behind that. So if you’re writing a real-world book about a certain time and place, you can research that time and place. If it’s a fantasy book, and you can think of some sort of model or analog to your work, then research from that can be immensely useful. So that’s the one thing.

The other thing, which is maybe more broadly applicable, is I think a lot of times — I will say the B-word — a lot of times, writer’s block comes from perfectionism. And it comes from the fact that when an idea is in your head, it’s beautiful and pristine, and as soon as it’s on paper, you see its limitations, you realize how obvious or unoriginal, or you convince yourself that it’s obvious or unoriginal. So I have learned to just embrace the crappiness of my first drafts. I just know from experience that the first draft of anything is probably going to be horrible. And that you can always revise a bad first draft, but you can’t revise a blank page. So I found that just forcing myself to get something on the page, even if I write 1,000 words and it results in one sentence that I can eventually keep, that’s one sentence more than I would have if I just didn’t write anything down.

BT: That’s — I think that’s very sound advice. Some of our listeners are younger alums who are, you know, trying to figure out their career path, trying to figure out what work suits them. What advice would you have for them on kind of finding your way as a writer, not just of children’s books, but overall?

JSW: Well I would say a few things. I would say one thing that is maybe advice I would give in particular to Princeton graduates, or graduates of other elite universities, is that you will see, just in your classmates’ Facebook pages, and the class-notes section, and also in conversation, you will see a lot about your classmates’ successes, and you will — you won’t see things about their failures, because people, understandably, are reluctant to talk about that publicly. But you will know all of your own failures intimately. And by the way, if I sounded a bit negative in the first half of this podcast, because I was talking about some of the failures and the frustrations along the way, it’s very deliberate, because I feel like people are not open enough about that, and it becomes easy to feel that you are the only one who’s struggling, or not where you want to be. So, I would just say that whatever path you choose, whether you’re being a writer, or an investment banker, whatever it is, you should be kind to yourself, and you should recognize that failing at things is not a sign of failure, it’s a sign of taking risks. And that is ultimately much more worthwhile, I think, than playing it safe.

The other advice I’d give is that I feel like I’ve always chosen to do the things that I love and am most passionate about. And that is a very risky thing, and has led to failures and frustrations, but it has been tremendously worth it. And I have absolutely no regrets about that. And so I would say that as big a risk as it might seem to follow your passions, I would just encourage you to do that, whatever that passion is. Whether it’s fiction writing, or nonfiction, or something entirely different.

BT: Jacob, thank you so much for joining me, this has been great.

JSW: Oh my pleasure, thank you so much for talking.

BT: Jacob Sager Weinstein is the author of, most recently, Hyacinth and the Stone Thief, which is due out May 15.

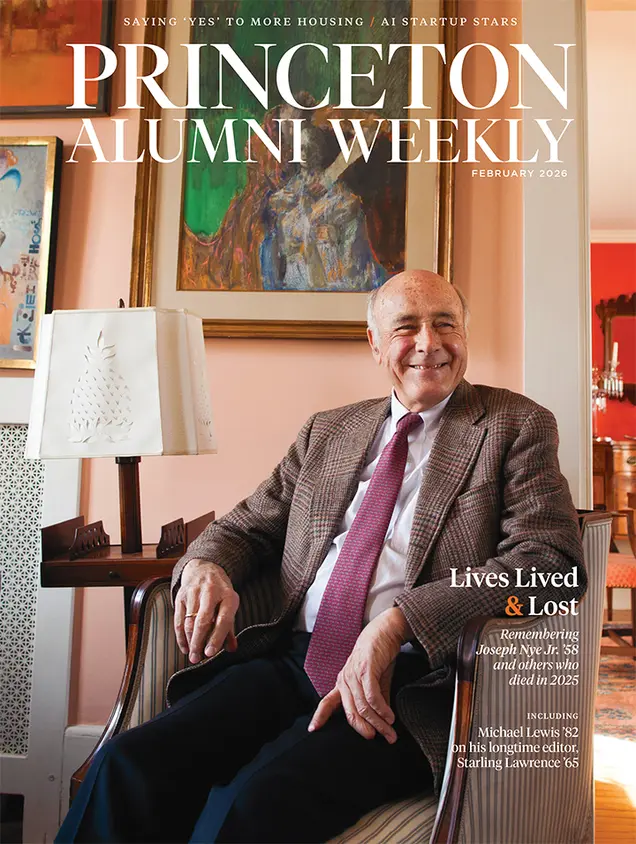

Paw in print

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

No responses yet