Q&A: Sean Gregory ’98 of Time Magazine on Sports, Beyond the Sidelines

PAW’s Q&A Podcast — January 2018

Are we entering a new era of the activist athlete? Will the FBI sting have a lasting impact on college basketball? And why is Olympic curling so popular? We talk about these questions and more with Sean Gregory ’98, a senior writer at Time magazine, in the January episode of PAW’s Q&A podcast.

This is part of a new monthly series of interviews with alumni, faculty, and students. PAW podcasts are also available on iTunes — click here to subscribe.

TRANSCRIPT

Brett Tomlinson: Welcome to the Princeton Alumni Weekly’s Q&A podcast. I’m Brett Tomlinson, and this month our guest is Sean Gregory, Class of ’98, a senior writer at Time Magazine who focuses largely on the world of sports. He’s had a pair of Time cover stories in the last few months, one in October written with Alex Altman about President Trump’s critique of NFL players and their national anthem protests, and another in September about the remarkable industry that’s grown up around youth sports in the U.S. This is our January edition of the podcast, but we’re recording in December. And it seems like a good time to talk about the major sports headlines of 2017, beyond the field of play. Sean, thank you for joining us.

Sean Gregory: Thanks, Brett, thanks for having me.

BT: And full disclosure, Sean and I were briefly teammates in the Columbia Grad School —

SG: Right.

BT: — Intramural Basketball League. Sean was our go-to offense threat, and I was one of the guys who would come off the bench and launch a couple terrible looking hook shots.

SG: I think we fought hard, but I think we lost to the astronomy department in the semis or something like that.

BT: Yeah.

SG: It was a sad ending for the journalism school.

BT: Hey, we gave it the old J-School try.

SG: Yeah, right.

BT: So the dominant sports story of recent months has been the NFL player protests during the anthem, and the president’s response, and also the public response. For Time’s Person of the Year issue, you’d recently wrote about Colin Kaepernick and sort of his unusual role as both the catalyst for this movement who at the same time is now removed from it a bit —

SG: Right.

BT: — since he has not been signed by an NFL team. I’m curious how you see Kaepernick, and those who followed his lead? Are we entering sort of a new era of the activist athlete?

SG: Yeah, I think so, Brett. I think it started to change around really, when you talked to folks about how kind of this evolved, around kind of when Obama was elected, in 2008. More players, particularly in the NBA, were vocal about their leanings, and a few campaigned for him, or advocated for him, at least.

But then we have the Trayvon Martin incident in 2012, 2013, and the Miami Heat led by LeBron James took a picture, they were all in hoodies and tried to make a statement that, what was happening wasn’t fair. They had a point of view and they expressed it, and this was after years and years of, kind of the Michael Jordan model in the ’90s that, “Republicans buy sneakers too,” don’t offend anybody — even though he might not have said that quote. But that was the general kind of philosophy.

So then you get into the election of Obama. You have these high-profile incidents with an African American president, and then it just kind of snowballed with Michael Brown, and Ferguson, and into the last — to the summer of 2016. And then when Kaepernick takes — he started by sitting and then had some very pointed comments about police brutality and racism and oppression, his point of view, it just kind of, it did kind of balloon and he evolved it to the kneeling after talking to some veterans. He thought it was a sign of respect, but there were millions of people who thought he was just blatantly disrespecting the flag, and first responders, and the military.

And then, it was — going into this year, he’s not in the league anymore, and that — there was activism about that, protests in NFL headquarters that, people supporting him thinking he was being blackballed, but there weren’t — the kneeling, there were a handful of, or maybe, nine or 10 players kneeling going into the weekend of week three in the NFL season, late September. And then once Donald Trump called them sons of bitches for doing what they did, it just — then it became activism against the president as well.

And so then you had that weekend where there was kind of the mass demonstrations, and it’s kind of — it’s gone in ebbs and flows, it’s kind of gone a little bit to the background now as we sit here in mid-December. Still an issue, but the owners have tried to squash it after it seemed like they were backing the players, they kind of backtracked. It’s been this crazy, weird year in the NFL where the business is down, and people are scrambling thinking oh, is it because of protesting players, is it because of the safety issues, is it because there’s too much football over the place? So there’s just a lot of stuff swirling.

So when you speak to folks like Harry Edwards, a sociologist from Cal whose has been — who helped organize the ’68 Olympic protest and has been studying this and helping organizing this kind of things for decades. I mean he’s very — when you ask him that question, he is very clear in his thought that yes, this is — we haven’t seen activism like this since the late ’60s and Colin Kaepernick is the Muhammad Ali of this generation.

BT: And the role that social media plays in all this, you don’t have to be an NFL quarterback, you can be a women’s national team player —

SG: Right.

BT: — you can be, basketball, hockey, baseball, on down the line (although baseball seems not to have had much of this).

SG: Right.

BT: And we’re also seeing coaches get involved in a way — with Gregg Popovich and Steve Kerr — in a way that it’s hard to imagine, a generation ago an NBA coach being so outspoken in the political realm.

SG: Yeah, think it’s a product of the conversation being 24/7, right? We have constant access to points of view and conversation, and it’s hard, for people not to get wrapped up in it and for people like Steve Kerr and Gregg Popovich and, Stan Van Gundy wrote for us an essay about calling the kneeling players patriots because they’re trying to improve their country, and he spouted all these stats about prison reform. He’s kind of studied the issues and kind of took the time to kind of learn what — learn about what his players, professional players around the country are protesting about.

So yeah, I agree, 10 years ago, 12 years ago, the mid-2000s it was a very — for the Iraq war for example, I remember Steve Nash spoke out about it. It was like oh, wow! And if that were to happen — if the Iraq War were to happen now you can just imagine, athletes would be very free to give their opinion. And I think, when the president of the United States is calling out athletes and making them seem like they should just be grateful for you’re making — you’re making millions of dollars, you’re playing a game, stick to sports, right? And that just raises — that just starts a fight, it’s a natural human reaction to say hey, wait a second, I have something to say. You can’t bully us. And so it, I think the divisiveness is coming from the top has really, helped this snowball and it will continue. There’s no reason to think that this new era of activism will stop any time soon.

BT: And the reaction to the anthem protest would not seem to be a net positive for the NFL, but it has perhaps overshadowed some other disturbing news, things on player safety. So this year, we saw the release of another major study of traumatic brain injury. More recently the revelation Aaron Hernandez the former Patriots player who was convicted of murder and who committed suicide and in prison had exceptionally high levels of CTE. What’s next for the NFL as these very scary health concerns continue to pile up?

SG: It’s a huge problem. How is it affecting — and it will be really interesting if the league or some third-party folks can really parse this out — are people starting to feel guilty about watching the NFL? Is that contributing to some of the, ratings, declines that we’ve seen. Now let’s be frank, I mean the NFL is still is very popular, right? I mean in the grand scheme of things, the other sports would kill for some of their ratings and the audience that they draw and the Super Bowl audience and all that. However, the news — I’ve been following this for 10 years now and it just never stops and gets worse and worse, another study, another study, more brains examined, more CTE.

And on the grassroots level, we’ve seen the participation decline, anecdotally and in data. And so what’s the player pool going to be, 10, 20 years from now? It’s a very intuitive thing.

And, when I interviewed Roger Goodell five years ago even he said, like, listen and, he has to be very careful because of all the legal things, but he said something along the lines of it’s pretty intuitive that banging heads all the time probably isn’t the best thing for the brain. And so in that very — you can make all the — you can make every safety rule, they’ve tried, they’ve tried with the safety rules although we still concussion protocols and what happened this Sunday there were — Tom Savage was obviously the quarterback for the Texans, right, he was obviously concussed and wasn’t taken right out of the game. So there’s flaws in that, the rules, you can have every rule on the books about don’t tackle headfirst, but there’s happenstance passes across the middle of the field where heads will collide.

I get pitched and speak to companies that are trying to innovate in helmets and, but that’s — every credible company will say a helmet can’t prevent concussions. Our science has shown that the G-forces will be lowered when you use our helmet, but some of these helmets there’s guys are still getting concussions in them. So, and we still have a lot to learn about repetitive hits with practices being cut a little bit and not as much head contact in theory, in practices on all levels, will we see these — the same level of CTE 20, 30 years down the road? But it’s a very scary thing that’s not going away. And the NFL, if you look at the sports landscape the NFL, if I’m buying stock, the NBA, I think is up right now because they don’t have these issues and they have these players that are, phenomenally talented, visible, marketable — the LeBron, Curry, Durant cohort. And then below that, you have coming up, the Greek Freak, Porzingis in New York, and Joel Embiid in Philadelphia; you have three guys and other guys that you can put in that category that can change the game as well. So they’ve got a plethora of marketable, exciting players without this kind of baggage.

Just looking at where the NFL is right now where it’s been and where it’s going, I could see why there would be a lot of concerns and they’re going to have to — it’s going to be a challenge for them. And these challenges aren’t going away, especially in the brain science stuff. I mean the anthem protests who knows what will happen there. If I’m predicting, I predict the president’s going to keep agitating on athletes because he, as a political strategy it might work because it rallies a lot of his base when he says hey, guys stick to sports. And so that might continue, but definitely, the brain science is going to get more ominous and so that’s — that challenge isn’t going anywhere for the NFL.

BT: Yeah, it’s scary stuff for sure.

SG: Yeah.

BT: And you mentioned the — certainly the pipeline issue, parents thinking about which sports to put their kids into —

SG: I mean why do — why risk it, right? I mean there’s plenty of other sports to play, for athletic kids to participate in. I think lacrosse even has kind of benefitted a little bit from football fears, and that sport has an opportunity to go to places where maybe it hasn’t been before.

BT: In college sports, the big headline was really a sensational story for a couple weeks. It’s kind of settled down, but the FBI’s probe into college basketball recruiting — which led to criminal charges and of course, the firing of Rick Pitino, the biggest name who was caught up in that. Will this scandal and the trials to come change anything? Or is this just sort of a momentary blip in the big business of college sports?

SG: Well, it might make people reckon and question why is this a federal crime? Why is a player that’s been determined to be worth $100,000, if he’s given that money — now listen, the way things were gone about were, trusting advisers because they were going to give you the best professional advice when they were really trying to funnel you to different places, it wasn’t — there’s no saints here. But, I think the reaction and it’s evidence of the — the paying-players debate has really changed in the last five years or so. There’s a lot of prominent voices, there’ve been lawsuits, Time magazine, square, old Time magazine wrote a cover in 2013 saying why —making the argument why college players should be paid, which I think kind of, I don’t think we’re — I’m being too immodest by saying that helped advance it or at least gave people a talking point to either agree or disagree with. It’s become, not gospel, but there’s more momentum, and more questioning of why the coaches at these big-time programs — we’re building $25 million locker rooms, but we can’t give a kid $100,000.

So it — I wonder if it’s less like these guys are — they are breaking the rules, I mean, right, the rules are on the book and they did cheat and the technical law stuff about wire fraud and all that, that all might be there but, I just found it interesting that the two scandals that broke that same week were the FBI thing and then the Carolina, their academic fraud deal —

BT: Right.

SG: — they got off, right. I mean they weren’t punished by the NCAA because of some loopholes, meanwhile they were all taking fake classes. So what’s the worse offense, right? Is it giving a kid $100,000 because that’s what the school values for his services, and giving it to him under the table because the rules says it has to be under the table; or being given an academic scholarship without any opportunity for additional compensation, and then being offered phony classes — so not getting the education you were promised.

So that’s kind of how I personally react, and it kind of put that in kind of my own context, having covered and written about these issues in college sports for a long time. So it wasn’t like oh, my gosh, the tragedy of what these guys were doing and again, there’s no saints here. Everyone’s trying to — there’s so much self-interest involved and Rick Pitino bending the rules, he deserved his punishment.

But I wonder if the fact that this is a scandal and is being discussed and there’s tip lines and will it make — will it give further momentum to the question of what are we doing here? It’s the argument for legalization, and of drugs, and other things. Why create an underground market when does it have to be an underground market? And that said the, will there be more programs to be affected by that because at the end of the day, the programs did break the rules, right, so the fans — it’s going to interest fans if the NCAA comes down on Louisville, or Arizona, or whoever else. So, but maybe the tip line — the tip line that the prosecutor said was wide open, maybe people clam up and it’ll be this case going forward, and maybe it’ll peter out. It wouldn’t be shocking if coaches just want to go about their business and not kind of jump in the fray. So it’ll be interesting — for sure. And, college basketball with the one and done, it’s a tough sport; stock being up and down, as much as we all love college basketball, it’s kind of become a little bit of a one-month situation. There are great teams, great players, like Duke this year, they’ve got a lot of good players and when an upset happens like BC beating Duke, it’s shocking and it’s charming.

Is there going to be any change with the one and done rule? Can there be kids, can there be teams that people follow and get attached to? Or is it going to be at the top levels, the one-year NBA training ground, which isn’t the best thing for fans, I don’t think. It’s fun to watch them play, but it doesn’t, you go back to like the Big East, you hate to say in the good old days, but the 80s Big East, which everybody loves. The thing that people loved about it that there were teams that developed and rivalries that developed over time. Now it’s all about the coaches and A, are they breaking the rules and B, what five-star can they recruit can they get for a year. So it becomes a little bit less attractive, I think for a sports consumer. But then once March starts, everyone gets into it so. It’s might be a one-month sport, but gosh, it’s a great month.

BT: It is a great month. Looking ahead — 2018, you’ll be traveling to the winter Olympics in South Korea.

SG: Yeah.

BT: Obviously, it’s a great event, but it’s also a time of real tension in on the Korean peninsula. What are some of the story lines you’ll be following as you ramp up for it?

SG: Yeah, I think, once the Olympics begin, it’s always about the athletes. I think that’s the one thing I’ve learned doing this a while. It becomes, what did Mikaela Shiffrin do during her slalom, what did Sean White do today, what did Lindsey Vonn, what do the big star names do in their events? They become stars for a very finite amount of time, but during that time they become, arguably the most famous athletes in America during this two-week window. So there’s intense interest in sports like figure skating; Nathan Chen — the American strength this time around is on the men’s side and he’s a phenom, a young phenom, so he’ll be a big name.

And so, there’s the athletes and, going in yeah, there’ll be plenty of stories, looking at what safety precautions folks are taking and, I think it’s going to be fine. I don’t think there’ll be nuclear war while the Olympics are going on, I think there was some chatter coming out of political circles last week, early December about the United States — people shouldn’t be going — traveling to South KoreaThe Olympic team might not go, and that was just miscommunication and political posturing, I think. There’s no way the United States isn’t sending a team, minus a severe escalation of what’s going on on that peninsula in that part of the world.

The Russians not being there is a huge story, or some of them being there, under the Olympic flag competing as quote unquote neutral — I mean the ultimate triangulation, right, I mean. All right, so the Russians cheated. We know the Russians cheated. And but I understand it’s a little bit of what the IOC comes from, maybe not all the Russians cheated. So we can’t punish everybody, but we’ll — so the clean athletes will have to go for all these tests. But they can’t compete under the Russians flag, but they will be identified as coming from Russia.

So it’s — listen, the bottom line is in the medal count the geopolitical battles that go to the sporting field, the U.S.-Russia rivalry, especially when stuff is tense between the countries is always dramatic. And so from a sports fan point of view, it’s a two part problem: The Russians cheated and they used their home country in Sochi, their home lab to cook urine samples and escalate to the medal tables as the ultimate home cooking, and then so not only that and now because of their bad acting, these — some of these Olympic rivalries, U.S.-Russia matchups are, they cheated so they’re not going to be there and that’s fine but from a sports-fan point of view you kind of want to see that so. So that’ll be a big story.

And, in every Olympics, there’ll always be something that happens that you don’t know about, a Ryan Lochte situation or, or, a nice story like Gus Kenworthy and he’s a freestyle skier who, assuming he makes a team, will be the first openly gay man to compete in the winter Olympics. He, came out after the Sochi Olympics, but during the Sochi Olympics he adopted a bunch of stray dogs, and that became a kind of feel-good story, Sochi had all these dogs wandering around, and he brought them from Russia back to the U.S. So there’s always these, like, these scandals and these nice, feel good stories that happen that you can’t predict, and that you just kind of go in ready to scrap every plan that you have.

BT: And I’m just looking for the relaxing experience of watching curling.

SG: Well, as soon as you started to say that, I knew you were going to go to curling, and you’re absolutely right. And, I think, we well — we’re planning on doing and it’s going to be up hopefully by the time this podcast is out, if it’s not look for it on Time.com a video animation explaining how curling is scored and how you should watch it so. We were trying to serve the customers their curling obsession. I believe CNBC — I might be wrong about this, but NBC goes big on curling, and CNBC might be all curling, all the time. Maybe it’s not CNBC, it’s one of their networks is like just dedicated to curling.

BT: Will there be funny looking pants again?

SG: I’ve got to get on that. I’ve got to start scoping that out. I should get the scoop on, like, the Norwegian pants design. Yeah, it’s — and it’s actually not a hard sport to follow once you kind of — I can see the appeal from a TV point of view. The sheet of ice is there, it’s like darts, once you figure out the scoring system it’s actually pretty intuitive and interesting. So I hope to be spending some time on the sheet, Brett, I think they call it the sheet.

BT: On the sheet.

SG: On the sheet, yes, with the rocks and the — in the house is like the dartboard looking thingy. So bring it to the house, we won’t be in the house for the curling in South Korea.

BT: I’ll get you out of here on this one. You were a Wilson School Major at Princeton?

SG: Yes.

BT: A varsity basketball player. Now you’re covering sports and the myriad real world issues that intersect with sports. How did Princeton prepare you for the work that you do?

SG: It’s funny you mention the Woodrow Wilson School, and I’m so glad I found the Wilson School and studied urban policy and urban planning. And then I joke, when I was at Time one of the early — we started doing videos, and one of the early videos I did was with the Nathan’s Hotdog – what’s that guy’s name? Joey Chestnut. Joey Chestnut — and I went in and I made a hot dog with him, and I almost barfed on camera and it was ridiculous. And the joke was, like, well, this is why I went to the Wilson School to eat hot dogs on camera and almost puke. There’s that end of it.

It wasn’t — what I’m doing now isn’t directly related to the urban planning, urban policy stuff that I did study; however, covering sports now and especially at Time, you just have to have a sense of politics, economics, science, how things work, and the Wilson School’s actually a great education because, you don’t major in one thing — you take some economics classes, you take some politics classes, you can take science, you can kind of experiment on different things, and not be an expert at one thing but be familiar with a bunch of different areas and that’s what I do now. It’s like I get to, study psychology in sports, and economics in sports, and health in sports, and just like at the Wilson School, there’s public health, there’s public policy, public economics. It’s a good blend of everything. There wasn’t a sports component at Woodrow Wilson, but I basically took a lot of what I learned there and the interdisciplinary curiosity that it sparks and kind of applied it to my job. That’s really been helpful. And, basically, with Princeton, the connections I made — it’ll take 20 minutes to explain, I won’t bore everybody — playing basketball, and being at the school I just made a ton of fortuitous connections that just helped set me on my way, or opened the door, or sparked an interest. And so I look back now and being at Time for 15 years, I just know piecing it together, it never would have happened. I’m not saying that because it’s the Alumni Weekly podcast, and I’m not shilling for the school at all. In my case, it’s just a fact that if I wasn’t there at the time and didn’t meet the people I met … I’d be married to somebody different, for example. I met my wife through the school, through the town, and definitely got to where I am through that. So I’m very, very lucky.

BT: Well Sean, thanks so much for taking some time to talk. I really appreciate it.

SG: Always fun talking Brett, anytime. Thanks a lot man.

BT: You can read Sean Gregory’s coverage of the Winter Olympics and other sports topics at Time.com. If you’ve enjoyed this podcast, please subscribe and leave a review on iTunes. We’ll be posting more interviews with Princetonians throughout the year. We also have an oral-history podcast called PAW Tracks that features stories from alumni, in their own words.

Paw in print

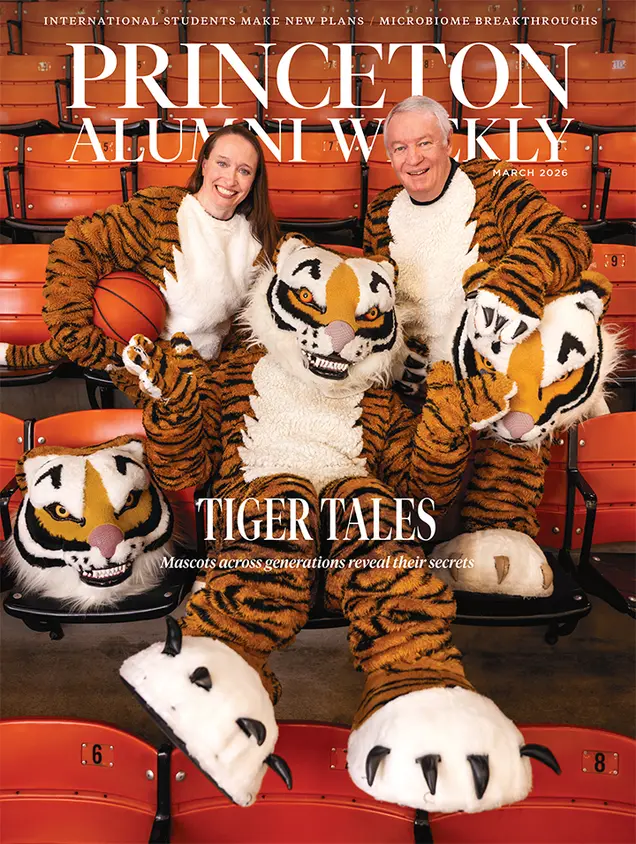

March 2026

Mascots across generations; biome breakthroughs; international students make new plans.

1 Response

Norman Ravitch *62

8 Years AgoUniversities in most...

Universities in most countries other than in ours do not have sports on the menu. Our practice comes from English schools and universities where sports were supposed to train men in manliness; I suspect that the real reason was to discourage sexual encounters with women. In any case, sports is one of the most important means for men to avoid personal meaningful contact with other men. You can always talk about sports, statistics, players, and all the rest -- a wonderful way of avoiding talk about anything truly important like politics, religion, and sex.