Q&A: Singer-Songwriter Anthony D’Amato ’10 on the Touring Life

PAW’s Q&A Podcast — February 2018

Anthony D’Amato ’10 has come a long way since he began writing and recording songs in his Princeton dorm room nine years ago. He’s released three full-length albums and toured across the world, and his indie/folk and Americana-inspired music has been compared to the likes of Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen. In an interview with PAW’s Allie Wenner, D’Amato talks about his Princeton roots, the touring life, and what it’s like to be on the road in the current political climate. The podcast includes performances of “Honey That’s Not All” and “Rain On A Strange Roof.” You can hear more of his music on Spotify and Apple Music, or on his website, anthonydamatomusic.com.

WATCH D’Amato perform “Ballad of the Undecided,” a song he wrote as a Princeton student

This is part of our monthly series of interviews with alumni, faculty, and students. PAW podcasts are also available on iTunes — click here to subscribe.

TRANSCRIPT

Allie Wenner: Anthony D’Amato ’10 has come a long way since he began writing and recording songs in his Princeton dorm room nine years ago. He’s released three full-length albums and toured across the world, and his indie/folk and Americana-inspired music has been compared to the likes of Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen. Most recently, he released a charity EP called “Won’t You Be My Neighbor.” And the proceeds from that are going to the International Rescue Committee, an organization that offers emergency assistance to refugees. I’m Allie Wenner, a writer for the Princeton Alumni Weekly, and I recently sat down with Anthony in the Princeton Broadcast Studios to talk about his songwriting process, his recent performances and travels to a music festival in Mexico, and what it’s really like to be an American artist touring the world in the current political climate.

And by the way, the song you’re hearing right now is called “Ballad of the Undecided,” and if you’d like to see a video of Anthony performing it live for us in the studio, visit paw.princeton.edu.

Allie Wenner: I am here today with Anthony D’Amato, who has taken at least one train down from New York to be here in Princeton today.

Anthony D’Amato: One train, plus a Dinky.

AW: One train, plus the Dinky, so...

AD: Yeah. Don’t forget the Dinky.

AW: So, I just wanted to say, thank you so much, Anthony, for coming all the way down here today.

AD: Thanks. Thanks for inviting me back.

AW: And, I’m sure you’re thrilled to be in the frozen tundra of New Jersey in January after being in Mexico for week.

AD: Yeah, well, you know. It’s not quite the beach in Todos Santos, but I’ll take it.

AW: Yeah, so, speaking of Todos Santos, the festival that you were playing at, it was called Tropic of Cancer?

AD: Yes.

AW: So, tell me about that. I mean, was it right on the beach? Were there tacos?

AD: It’s — it kind of — it kind of takes place over the whole town. Todos Santos is this cool little artist community down there, and there’s a lot of expat, you know, Americans are down there. There’s folks from Europe and all over the world who kind of resettled there because it’s this beautiful area along the beach. Like, lots of mountains and little hidden coves, and then tons of — you know, local and transplants — artists are there. And, they’re — you know, the streets are lined with these galleries of, you know, sculptures, and painters, and weavers, and all sorts of stuff like that. And this festival takes place over about the course of two weeks, and a lot of artists come down and they play, every night there’s, you know, a show at a different kind of space in town, and then there’s an after-show somewhere else, and it kind of just goes from about sundown until, you know, 2:00 in the morning every night.

AW: Cool. So, what was that experience like. I mean, was it a lot different from playing, like, a festival or a show in the United States?

AD: Yeah, it’s rare that I would go somewhere and just be there for a week. When I’m on tour, it’s usually a new city every single day. Even with a festival, it’s usually just, you play there that day. Maybe you stay the weekend if you have the next day off, but generally you’re go, go, go, go, go when you’re on the road. So, this was interesting to just kind of plant myself in one place for that long. And, also, in, you know, in a cool, historic, little town like that in Mexico. It was just a very different vibe. When you fall asleep, you can hear the ocean waves crashing, and there’s stray dogs all over this town that are kind of, like — they seem to have become part of the fabric of the community. People leave them food and stuff, and so, you know, it’s just a — it’s a very different vibe than Brooklyn.

AW: So, 2017, that was a pretty big year for you. I just know you went to Europe twice for two different tours. So, tell me about that. I mean, I assume it was fun, or you wouldn’t have gone back a second time.

AD: That — yeah. That was great. The first time I went over with this band, The Mastersons, who — they play as Steve Earle’s backing band. They’re a husband and wife duo — they’re fantastic. And, I did about a month of shows with them last January into February. And then, in the fall, I got invited to go do about a month of shows with this artist, Ricky Ross, who — he’s from a band called Deacon Blue, which is kind of — I was just trying to think of an equivalent — it’s kind of like a Springsteen of Scotland, you know — it’s kind of like working class, blue collar, rock and roll, and, you know, they had number ones over there in the ’80s and ’90s, and play arenas, and that kind of stuff. But, Ricky put out a solo record, and he’s a host on the BBC now, which is how I met him — I got interviewed on his show a couple of times. And, when he put out this solo record, you know — again, the sort of thing where I, you know, reached out, and was just kind of, like, “If you’re looking for support for that tour, you know, let me know, I’d be — I’d love to come and play with you.” And, they were totally into it, so they invited me to come over and do the whole tour. So, that was just Ricky on piano, and me on guitar for the night. And then we added a bunch of shows around that, so yeah — the second run in Europe ended up being a full two months over there.

AW: So, what was it like touring in Europe, as an American, I guess, given the current political climate?

AD: You know, the first Europe run last year in January, it started on inauguration day.

AW: Oh, wow.

AD: Yeah. And, in my mind, I was psyched to get out of America for that. I thought, great, you know — this will be a nice break from the ugliness that’s going on. But, you know, it — the thing I feel like I learned is that American politics really are world politics. Like, everywhere you go over there, everybody knows what’s going on. Like, you go into the corner store, and they want to talk to you — they see you’re American, and they want to talk to you about, you know, what’s going on. Like, why did you elect this guy, and... And, they know — you know, they know a lot more about American politics than, I feel like, Americans know about any other country. You know, they’ll — if you’re talking about Trump and say, “Well, you know, we’ll see how long he lasts.” And, the guy in the shop will just be like, “Well, then you got Mike Pence, and I don’t know that he’s much better.” And, I’m, like, “Man, I don’t know who the vice president of your country is.” Like, that makes me feel like I’m in this, you know — in this, you know, very American-centric bubble that we all kind of live in. But, American politics really matter to the rest of the world. So, I was not able to escape it. Everywhere I went, people wanted to talk about it, and ask about it. And, you know, when I’m over there, also, my phone doesn’t work. I can only, you know, just when I’m on the wi-fi. So, I’d kind of, like, go a whole day being blissfully unaware of what was happening, and then I’d get to the hotel at night, and turn on my phone, and it would just be like: travel ban, protest, this, and that. And I was like, “Oh, God.” You know, everyday it was kind of — you’d start to dread when you got back on the internet, because what crazy thing happened?

AW: And this leads in nicely — I wanted to ask you about — I know you’ve released some politically charged music —

AD: Oh, yeah, yeah. The —

AW: — this year.

AD: — the charity EP.

AW: Yeah, Won’t You Be My Neighbor? — the EP.

AD: Yeah, so that was — that kind of started in that winter tour in Europe. I was feeling kind of helpless being so far away from home. You know, watching my friends go to these protests, and, you know, I wanted to make my voice heard, or — even more than that, I think, I wanted to channel the anxiety of being so far away during a tumultuous time like that into something positive. So, I decided when I got home, I was just in my bedroom, with just an acoustic guitar, going to record a handful of songs. Some of them were ones I’d written, and some were covers of songs that people wouldn’t normally think of [00:10:00] as political, but have become political in this time, where it feels like, just kind of being like a compassionate person is a political statement in its own weird way. So, that was where I got the idea of taking the Mister Rogers theme song, “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?”, and turning that into this folky protest anthem. Because, I can imagine Mister Rogers getting drummed out of town, you know, by certain politicians now for, you know, inviting illegals and terrorists, and whatever, into the neighbor— you know, like, that was kind of the message of that show was, you know, everybody’s welcome, and there’s a place for everybody in the fabric of this neighborhood. And, that’s not the way a lot of people feel right now. So, I wanted to — you know, I took that song, and a handful of others. I’d toured the year before with Ziggy Marley, Bob Marley’s son. And, he used to play “One Love” every night, and I’d never really paid that much attention to the song beyond just the chorus. And, when I was hearing that song every night, it struck me — the lyrics are — the versus are really beautiful. A lot of them are pulled straight from the Bible, and none of them rhyme, which is totally bizarre for a song, to have none of the versus rhyme. So, I took that, and I just slowed it way down into, like, a Leonard Cohen, kind of, finger-pick, spacey kind of thing. So, anyway, the idea was to just kind of reimagine some of these songs. And, it was going to be a benefit for the International Rescue Committee, which helps refugees around the world. And, yeah, once I recorded them, I was, you know, realizing there are a lot of other artists that felt the same way. So, I started sending the songs out to friends, and Josh Ritter sang on one of the songs, Sean Watkins from Nickel Creek, the Mastersons who I toured with — a whole bunch of friends.

AW: Yeah, speaking of Josh Ritter, I think my favorite song on that album is “This Land Is Your Land” —

AD: Oh, yeah.

AW: — Which he did the background vocals on.

AD: Yeah, that was really cool.

AW: Yeah, I loved how you kind of put in some clips of Donald Trump, and people speaking about things that had happened last year. That was really cool.

AD: Yeah, that was — you know, I feel like I waffled about recording “This Land Is Your Land” because that’s been covered a fair amount, but, you know, I wanted to do it using the original lyrics that Woody Guthrie had because there are verses in there about, you know, private property, and walls, that felt particularly relevant. And, I also figured if I was going to do it, I needed some kind of a new, current spin on it, so — yeah, that was my idea was to take some kind of audio clips of, you know, elected American officials, giving public addresses in which, you know — we can look back at them now, and say: wow, that’s incredibly racist; or, that’s incredibly sexist or incredibly discriminatory. And then, you know, things from the ’50s and the ’60s, whatever, and then put them along side comments from, you know, people like Donald Trump, or Mitch McConnell, now, where, you know, I think in a few decades, people are going to look back on those the same way we look back on some of these really, you know, ugly periods from the Civil Rights Movement, and, you know... I think, we’re going to scratch our heads a little bit at how we kind of accepted some of this as the level of public discourse.

AW: Sure, and, as you mentioned before, there are — it’s not all covers. There are a few originals on here. So, I’m wondering, you know, do you feel a sense of responsibility as an artist, and maybe somebody whose voice carries a little further than others, to speak out on social and political issues that are important to you?

AD: You know, I’m never really sure how far my voice carries, or, you know, on any particular project, you know, what kind of an audience is this going to reach. So, the thing that kind of guides me when I’m writing is just, you know, what’s on my mind, and what am I trying to work through and make sense of. So, that’s why I think, you know, my songs will be a mix of, you know, personal, inward-looking things, and then outward, more social, political-geared things because, you know, I think like any human being that my thought process at any given time is a weird blend of both of those things. So, you know, it’s not necessarily that I sit down, and I say, you know, “My opinion is going to change someone’s mind, and it’s time for me to write a song about how I feel about X, Y, and Z.” It’s more like, the way I write songs is often, you know — I’ll come up with some music first, and then I’ll just start it — kind of start singing gibberish over it until some words start to make sense and a song takes shape. And, in that way, I think whatever is kind of bubbling under in my self-consc— or, in my subconscious — is what tends to come out.

AW: Cool. And, let’s talk about Princeton for one minute — we are here. So, I mean, this is kind of where it all began, or at least some of it began. Right? Is it true that you recorded one of your first albums in a dorm room —

AD: Yeah —

AW: — on campus?

AD: I’ve recorded a couple of things in dorm rooms, and that was how I kind of learned how to start recording, and mixing, and producing, in the rudimentary way that I can. You know, when I get to make studio albums now, I work with professionals who know what the heck they’re actually doing. But, I, you know, I’ve learned enough from doing it in my dorm room, that the charity EP, I did that in my apartment in New York the exact same way that I did everything here in my dorm at Princeton. You know, all the stuff I learned making my own records here, is what I use to make that charity EP.

AW: So what was the setup like in your dorm — which residential college did you live in, and what was the — paint a picture of what it (overlapping dialogue; inaudible).

AD: Well, I was in Rocky. I think the recording that I actually released, that I made in my dorm, was when I was living in Little Hall. And, the setup — it was my laptop on my desk, and then I had a little preamp and a little microphone that I would just set up when my roommates weren’t around. And, you know, I’d get the guitar and the vocals down while they were gone. And then, after that, like a lot of the keyboard kind of stuff, that would just come from like a direct line in. So, I could, you know, my roommates could be around watching TV, and I just have my headphones on, the keyboard, and... And then, some of the songs that have like drums and stuff, I would get on the train to New York, and I’d — you know, friends who are musicians in the city, who had rehearsal spaces, and we’d go set up in their rehearsal space and record some drums or I’d go set up in somebody’s apartment and record them playing some electric guitar, and bring it back to Princeton and mix it. And, that was how I made the first kind of homemade stuff that I did.

AW: And was that Down Wires — was that the album that this was —

AD: Yeah. Kind of, have sort of let that drift out of print over the years, just because that never even got mastered or anything. It was, you know, as kind of barebones as it gets. But, some of the songs have kind of reappeared on proper studio albums over the years, too. So, it’s been harvested for parts, here and there. But, it exists. People still have copies of it out there.

AW: And I’m curious. I mean, how Princeton-inspired is Down Wires? I mean, I’m sure you wrote at least some of the songs while you were studying here.

AD: I wrote all of them while I was here. You know, I think the thing that had the biggest impact on me while I was here was working with Paul Muldoon. And, that was like this, kind of independent study that I worked up, where basically, you know, every so often, I would send him a batch of songs that I’d written, and he’d go through the lyrics, and we’d get together, and we’d just talk about them. You know, he would’ve marked up the sheet, and... And, it made me think about lyric writing in a different way. You know, it made me really conscious of, you know, imagery, and the threads that you tie, you know, through a song. You know, I think before that, I thought of songs as things that just come out of you, and that’s the song. And, I think after working with Professor Muldoon, I realized how much — or, just how important the sculpting part of it is. Like, once it’s out of you, sure that’s great. But, let’s actually sit down now with just a sheet of paper, and no music, and think critically about, you know, how these words all work together, and how you can tighten it up, and make it more impactful.

AW: That’s interesting. And, so do you still — I know you said, at least when you were a student here, that you would kind of write the music the first and then the lyrics would come later. Is that still — even after studying with Paul Muldoon, is that still how it generally works for you?

AD: Yeah. You know, on rare instances, sometimes like a lyrical phrase will stick in my head, or a song title will come first, and I’ll try to write from that. But, for the most part, usually I have some kind of a chord progression, or some kind of a riff or a melody or something. And, like I said, it starts off with just kind of singing gibberish, just until sounds start to make sense, or you start to get like a feeling, like this song makes me feel happy; or, this song makes me feel sad. And then, you know, you try to dig more into it. And, like, what kind of happy does this make you feel; or what kind of — you know... And, once you start to kind of narrow down that sort of stuff, you can start to figure out what a song is about. But, yeah, I tend not to — I don’t have an idea of what I want to write a song about, and then write a song about. I generally have an idea for what a song sounds like. And then, I figure out what it’s about after that.

AW: Very cool. So, what does it feel like for you to come back here? You’ve accomplished a lot in the eight years since you graduated.

AD: Oh, God, it’s been eight years.

AW: It’s been eight years. So, what is it like to be back, you know, where at least some of the groundwork was laid for your career?

AD: You know, I love coming back to Princeton. I don’t get back all that often now, you know. I try to come back for reunions if I’m not on tour. But, I don’t know, it’s a — I have fond memories of being here. I didn’t realize it had been eight years. That’s a —

AW: Sorry to drop that bomb.

AD: That’s a blow. But, no, I don’t know. It’s funny; I walk around and it’s — even just today, like, walking across campus from the train station over here, I walked past my old dorm room, all the way to my eating club, and turned, and, you know, that’s a trip I made twice a day — because I never got up in time for breakfast, but... So, yeah, that’s — you know, you kind of fall back immediately into — I don’t know if it’s like this for you, but for me it, like — memories are tied very strongly to like places, you know. So, I can be walking through Prospect Garden, and immediately flash back to, you know, that feeling of walking through Prospect Garden at, you know, 2:30 in the morning on a Thursday night or something, and... It’s, you know — it’s fun to be kind of transported back to a different time.

AW: And what can we expect from Anthony D’Amato in 2018?

AD: I am working on a new record. I did about half of it before I went over to Europe this fall. And, I’m hoping in the next month or so to get back out — I was recording out in Utah with this artist Joshua James who is a favorite songwriter of mine, and we met on a different tour in Europe, and kind of hit it off, and... So, I was working with him and his band out in Utah back in the fall, and I’m headed back out there again soon, hopefully, to do another handful of songs. And then, just working on a few other different things on the recording side. And, I don’t know exactly how it’s all going to turn out. It could be an album, it could be a couple of EPs. You know, it’s an interesting thing about the shape of the music industry right now, that — you know, I’m interested in experimenting with the idea of, you know, steadier releases of smaller amounts of music, rather than, you know, two years, and then a big album; and then two years and — you know, all the songs in one batch. You know, I think people’s listening habits keep evolving. I know mine do, anyway. And, I’m interested to mess around with the idea of kind of keeping a steady stream going, and something — you know, building up a quantity of recordings, and then being able to put that out as a steady stream so I could just keep on the road, too. That’s the other thing is, you know, you have to take a lot of time off the road to write and record, and all that sort of stuff. And, my favorite thing is touring. I just love to be traveling and playing shows, so... You know, if I can build up a year’s worth of recordings, and then just go out and hit the road, and then just — you know, every couple of months, put out a couple of songs, that would kind of suit me ideally.

AW: Cool. Well, I look forward to maybe seeing some new stuff from you on Spotify in the coming months.

AD: Yeah, stay tuned.

AW: Awesome. All right, well should we do this music thing?

AD: Yeah, let’s do it.

AW: Would you like to play a couple songs for us?

AD: Absolutely. This is a song called “Honey That’s Not All,” which I wrote on one of my first trips over to Europe on tour a few years ago. But, it’s — finally recorded it on the new album Cold Snap, which I made out in Omaha, Nebraska with some of the guys from Bright Eyes. [Music]

AD: This is a song called “Rain On A Strange Roof,” which is — we talked before about the idea of how songs come to me normally, and this was one of the rare ones that actually — I had the title before I had any music or lyrics. It was a line that I’d pulled from Faulkner. There’s a bit where he talks about the sound of rain on a strange roof, and I just thought that was such an evocative line that it needed to be a song, so I went home and wrote this. [Music]

AW: You can hear more from Anthony on Spotify or Apple Music, or you can visit his website at anthonydamatomusic.com.

And if you’ve enjoyed this podcast, we invite you to subscribe in iTunes. We’ll be publishing more interviews, along with our PAW Tracks oral history podcast, all year long.

Paw in print

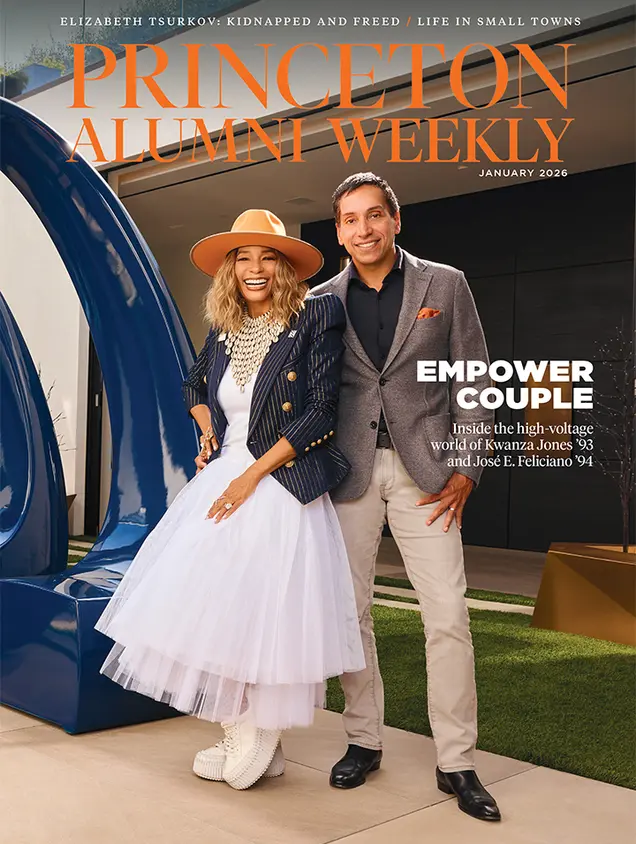

January 2026

Giving big with Kwanza Jones ’93 and José E. Feliciano ’94; Elizabeth Tsurkov freed; small town wonderers.

No responses yet