Raphaela Gold ’26 Reported on Student Mental Health for the ‘Prince’

‘I hope that students take away kind of an ethos of care towards each other’

Student journalist Raphaela Gold ’26 spent more than a year researching mental health care on Princeton’s campus, and particularly what happens when students experience the most severe crises — the kind that might require a leave of absence. This summer she published the story on The Daily Princeton’s website, adding significant insight to the ongoing campus discussion of student mental health at Princeton. On the PAWcast, Gold discussed how she got at this story, which included sensitive interviews with students, as well as where her reporting led.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT:

This is the Princeton Alumni Weekly’s PAWcast, where we talk with Princetonians about what’s happening on campus and beyond.

At the end of July, a pretty big story appeared on The Daily Princetonian’s website, one that took Raphaela Gold, from the Class of 2026, about a year and a half to report. It was a deep dive into mental health care on Princeton’s campus, and in particular into what happens to students who experience the most severe crises, the kind that might require hospitalization or a leave of absence. Gold centered the article on students who shared their own stories, and the result, as she wrote, “provides a window into the difficult decisions at the heart of that balancing act, one where each student’s case may be different and challenge the system in new ways.”

LD: So Raphaela, thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me about this.

RG: Thank you for having me.

LD: Where did the idea for this story come from? Was it from you? Was it from the Prince? You’re a features editor, and I think you were last year as well. Did anything in particular prompt this?

RG: Yeah, sure. So, it was kind of one of those pieces that arises out of a general instinct that you kind of want to follow through and see if there’s any there there. So I was approached by a couple other editors who had this idea swishing around in their brains that perhaps there was some kind of difference between how students see mental health and how the administration sees mental health, and this was prompted by a conversation that was happening on campus almost two years ago now about academic rigor and how that influences mental health.

So there was a statement made by President Eisgruber that academic rigor doesn’t have any negative impacts on mental health, and some students reacted to that, saying that they strongly disagreed with that statement, and that they did not see academic rigor as necessarily contributing super negatively to mental health, but that it can. And so we had this sense that maybe administrators and students didn’t necessarily see eye to eye when it came to mental health, and we wanted to understand, how do administrators see this issue and how do students see this issue? And is there something deeper here that we can get at?

So that’s where it started, and really we began by just seeking out students who had gone through some kind of mental health crisis at Princeton. And that’s where the more serious valence of the article came about, where we started hearing these really severe stories and we thought, “OK, let’s dig more into this and try to actually map out the entire ecosystem of mental health resources here on campus, and what’s there for students and what isn’t.”

LD: Was it difficult to get people to talk to you about this, both from the student side and from the University side? Because you also talked to a lot of the people who work in mental health at Princeton. How did it go?

RG: Yeah, it was a little bit difficult. Obviously this requires a lot of vulnerability from students to talk about, and it’s not always a comfortable issue for administrators to talk about either, so on both sides it involved gaining a lot of trust and having really long and serious conversations.

In terms of finding students who were willing to share their stories, that actually wasn’t as difficult as expected. This is a story that students know. A lot of students contend with mental health difficulties while on campus, and some of those escalate into more severe emergencies. And people who have been through that, or at least the people I spoke with, were really open with me and really willing to share what had happened to them and what they had gone through, and so I really appreciated that.

And then the administration too, gaining access to high-level administrators, the head of CPS and the assistant dean of student life. Both of those interviews were really kind of unexpected, but I was very glad to get those, because I think they really enhance the piece. I think often you just get a comment, and it was really great to get real conversations with these people so that they could explain how, on the administration’s end, people are actually thinking about these issues.

LD: So, could you describe, if you can — this is so much. If you could just describe what it is that you found as you went through this reporting, and also I’m curious: Did anything surprise you?

RG: I would say some things surprised me and some things did not. What didn’t surprise me was that there are a lot of resources for mental health for students on campus, and that students know about them. The University does a really good job of advertising these resources during orientation for freshmen. First-years all know what CPS is. And another thing that didn’t surprise me was that the adjustment to Princeton is really hard for first-years, and so a lot of students who are having more difficult times on campus tend to be first-years.

But I guess a few surprising things were both that mental health concerns surpass first year and go on into all other years of Princeton, and I guess also that I had not known about Princeton House, the mental health and behavioral health center that is run by Penn Medicine, before reporting this out. I hadn’t known that that was a place that students went. I hadn’t known that around 30 students are hospitalized every year at Princeton due to mental health issues and that it was just so much more common than I expected, and so that was a real surprise.

And one of the biggest findings of the piece was that it’s not abnormal for students to be hospitalized when they have a severe mental health crisis while on campus, for several days, at a facility that’s separate from Princeton University’s facility. So that was news to me, and really interesting to hear about that process and how Penn Medicine is actually able to really help students. And this is not the only place, also. Princeton House is not the only place that students experiencing these mental health crises go.

LD: I would imagine a student going through a crisis might feel like they’re the only one if they’re not aware that this happens. You know what I mean? What do you think?

RG: Yeah, absolutely. And to clarify, the 30 students includes both graduates and undergraduate students, so this is not to say that this is happening right and left all the time on campus.

And it’s been really interesting to hear from students the responses that I’ve gotten to this investigation. Some people come up to me and say, “I had no idea about any of that, wow,” and then there is a whole other subset that comes up and says, “Oh my God, this exact same thing happened to my friend, or to my friend or to my friend.” So for some, this is a story that they really know intimately, and maybe it’s one of those things where if you know, you know, but I think that now, at least, there is a general awareness.

And also, for the students who went through this themselves, at least after the fact, I think they came to an understanding that they are not alone in this, either through meeting other students who had gone through the same thing or, after their experiences, beginning to work on making mental health easier for other students at Princeton. They kind of tapped into this community of students who had gone through similar things, so a lot of the students I interviewed knew other people to whom the same thing had happened.

LD: I would imagine that that’s pretty important, just normalizing it. People feel that they can ask for help. You know what I mean? It goes to reducing the stigma.

RG: Definitely. I think that especially when it comes to also even the conversation around leaves of absences, and that on the other end, when a student maybe comes back from a mental health emergency, being hospitalized, or when a student is just experiencing some kind of mental health crisis on campus, that it’s normal to think about taking a leave of absence, that it’s also normal to experience a mental health crisis while on campus. I think that that was a really big, important thing that this piece brought to light, but also something that students kind of knew beforehand too.

LD: You talked about the resources for mental health care. And I’ve been watching this, and I’ve done some pieces for PAW in various ways on mental health, and so I know, and I’ve heard this before, that the resources here really are a lot. The University has increased them a lot. Your story got to that really well, how coming out of the pandemic really prompted a huge increase, which is amazing and wonderful, but your story also showed that it doesn’t seem like resources are enough. Not that the resources aren’t enough; it’s more like there’s more going on, there’s some intangibles, there’s other things going on. Can you talk about that a little bit?

RG: Yeah. I think the word “intangibles” is really critical here, because each individual case is different. Princeton, and really any institution trying to create a system that works for everyone when each individual case is different, will; there will always be a few holes. There will always be some ways in which a particular case might challenge a system, even when that system has been well thought through or a lot of money has been thrown at it.

Another really important thing to note, I think, is just that students at Princeton are not alone in their mental health experiences. Princeton as a university is not alone among U.S. universities and colleges when it comes to mental health issues. So this is really a nationwide crisis for youth, and it definitely got worse for everyone during the pandemic.

And so Princeton is really uniquely situated as an institution that has a lot of money and a lot of staff to think about this issue and how to go about it in a constructive way, so that’s meant a lot of advances in recent years, from smaller things like revamping websites to make them really easy to navigate, which can actually make a big difference for a student who needs to find a resource fast and who maybe doesn’t want to spend a ton of time on it, and also more significant things like reducing co-pays for outside practitioners from $20 to $10 last year, and also making it easier to take a leave of absence and to come back from one.

So these kinds of changes really do change the game for students, and at the same time, what a student experiences when they’re in that state of difficulty is not necessarily — you’re not necessarily going to feel helped, even if the resources are technically there. There might be a case where the University gives a plan for a student to do when they go back home, but those kind of resources don’t exist around where they live, or their parents don’t have time to do XYZ with them that’s part of their treatment plan during their leave of absence, or that kind of thing. Or perhaps even, for some students, $10 co-pay is still a strain on their budget.

That’s also really important to think about, that individual cases might still challenge the system, and that when these cases become a pattern, there might still be things to reassess within the system.

LD: Sure. The financial part of it, which the story got into really well, and you had students who illustrated that ... That surprised me, which probably tells everyone something about the position of privilege that I’m in that I hadn’t even really thought about it, that there could be students who, if they have a crisis, it creates a financial problem for their families, and that made me wonder if it could be a deterrent. And there are a lot of resources here to help, but as usual, whenever you’re navigating through a health care system, any health care system — we’re in America — can be really difficult, and that surprised me.

RG: Yeah, me too a bit. Some students get to Princeton from low-income backgrounds, or not, and have never engaged with therapy before, and think, “This is my chance. I’m going to go and take advantage of this free resource and try out therapy, see what it’s like.” And then maybe things come up from when they were in high school that they weren’t expecting, and they need to work through those while they’re on campus. That’s one thing.

And then also, even those who have been in therapy before and have pre-existing mental health issues on top of, perhaps, academic strains, and may be coming from a school that didn’t prepare them so well for Princeton’s academics, those things can exacerbate each other and become a bigger problem for a student. So that’s kind of on the front end of things when someone is just kind of encountering these difficulties or trying to work through them while being a full-time student, making friends, adjusting to Princeton, or even having been here for a while and just going through a regular semester at the same time.

And then on the other end of things, when somebody gets a big bill from a hospital and wasn’t expecting to go to the hospital in the first place, wasn’t expecting to need to pay the bill from the hospital and can’t get all of that covered by Princeton’s funds ... Maybe they get half of it. That was what one student experienced. She got about a third of it covered by the university, but the rest of it is a really big financial burden on the family.

And so yes, that can be a deterrent, maybe for someone going to an inpatient facility could actually really benefit them. The students who went found that it did benefit them. One can really push back against that when somebody’s thinking, “I’m going to have to pay for this,” and so that can prevent somebody from getting the care that they need.

LD: I’m sort of eternally interested in the question of Princeton’s student culture, which is — culture kind of just materializes. There are various factors that go into it. And that question that you mentioned that prompted all of this, of academic rigor and mental health and how they interact: What did you find out about Princeton’s student culture as you were going through this, and where did you land on the question of academic rigor?

RG: Student culture is hard to put a finger on. I think there are many different student cultures at Princeton, plural. There are lots of little bubbles. Everyone kind of goes through life a little bit differently here and picks their own pathway and challenges through Princeton. I don’t think that there really is any one way that students overall think about mental health and academic rigor.

There are differences of opinion about it within the student body, which we got in the Prince after that statement was made a couple of years ago. And based on this piece, I think the most common thing that one sees is somebody already dealing with something or other with their mental health, and academic rigor on top of that being something very difficult to contend with.

Often administrators in those cases think, “OK, well, great. This is the perfect candidate for a leave of absence.” They want students to be able to really fully take advantage of Princeton and everything it has to offer academically, extracurricularly, socially while here, and if they think somebody is being prevented from doing that, that’s a moment when they would encourage somebody to take a leave of absence. Very, very, very rarely is it required that anybody take a leave of absence, especially for mental health. It’s very rare.

Students in those situations don’t always see that as helping them. They might see it as, “I want to either just plug away at it and get through it and prove myself as a Princeton student.” That was one of the most striking things that the source that I opened the story with said to me. She said, “I felt like I failed to become this version of a Princeton student.” And so, I think people have this image in their heads. You’re supposed to be academically perfect, doing all these extracurriculars, and just kind of floating through it, and when that really is impossible, as it is for so many humans, people feel like they’re failing even if they actually aren’t.

So I think that that is a really difficult tension that feels really, really hard to resolve. And I don’t think that this piece got at a resolution. I think it more just laid out these two not-conflicting visions of academic rigor and mental health exactly, but just like, there is a tension there that maybe will be eternally worked through.

LD: I can really imagine it from the administrator’s point of view too, working with a student who feels like that. How do you even make that student stop and take care of themselves? It really does. I think it illustrates so much, like you said, just how difficult these cases could be when you get into individual situations and how different they are, and how carefully they need to be handled, and just how complicated.

RG: Yeah, it puts people in a tough bind. And it’s kind of this nationwide, universal issue that boils down to how individuals are feeling in a particular moment in a particular place, and those kinds of problems, I think, are always the hardest ones. So, this is a hard problem.

LD: You talked a little bit about the reaction from students. Did you get much of a reaction from the University or from the mental health staff here? Did anybody say anything to you?

RG: Not so much on that side of things. I would say we had been talking a lot throughout the piece. Administration, University Media Relations were really helpful to me, actually, in securing these higher-level administrative interviews. So everyone on the administration’s end kind of knew it was coming, and we had been chatting about it, so I think they were glad to see it go out. Yeah, I think that’s the most that I got from administration.

LD: What would you like people who read this and are thinking about this topic to maybe take away from it or be thinking about?

RG: I think what you got at a little bit earlier with normalization and destigmatization of this issue is really important. The students who are thanking me for this piece were the ones who said, “Oh, my friend went through something really similar,” and kind of just ... I hope that some students feel seen in this piece. I hope students who don’t at least learn about students who are going through more severe things mental health wise.

I think sometimes even students push it aside, don’t want to think about this, even when other students are dealing with really difficult things. So I hope that, yeah, students take away kind of an ethos of care towards each other.

And yeah, I think in terms of what can be done going forward, I think Princeton’s administration can look back on the progress that it’s made in the past few years and be pretty proud of itself and keep going. Hopefully what this lays out and what people can take away is just the many different factors and complications that come into mental health, and that it’s not just one thing, and that professors are thinking about it, students are thinking about it, administrators are thinking about it, everyone from a different angle.

Professors are another really key part of this puzzle, I think. You often don’t see the full student. You’re just seeing them in an academic setting. But professors at Princeton tend to really want to help their students and see them thrive, so knowing what a student might be going through other than classes is something important to think about and a lot of professors are seeking — one professor I spoke with said that what he was seeking was a human response, not just, “Give me a policy, give me a place to send my student,” but also, “What am I supposed to say to them in the moment when they’re going through something?” and that kind of thing. So professors are also looking for guidance is one thing to take away. Yeah, just that this is really complicated. So, I hope that it at least makes people think.

LD: It feels like the path is there and it seems like the University and everyone involved is sort of on the right path here. That was a takeaway that I got. Not there yet, maybe, but definitely working on it.

RG: Yeah, definitely working on it. I think something really challenging in the piece is the background of student deaths that Princeton has contended with. Most students on campus now have been on campus in a time when there was a student death due to some mental health related cause. I think that’s something that often just makes everyone stop for a moment and reflect, but then things continue business as usual a little bit directly after. And so that’s something that also came up with the students that I spoke with, was this idea that that is one piece of the puzzle that has been really, really difficult and a strain on students and on the administration. Yeah, something that the University is definitely still figuring out.

But I do think that you’re right to say that there is this overall sense of being on the right path and moving in a direction towards something better.

LD: Well, thank you so much. I thought it was a really important piece and I’m really happy that we were able to bring this conversation to alumni.

RG: Thank you so much. I really appreciate it, and have a great day.

LD: Thanks.

PAWcast is a monthly interview podcast produced by the Princeton Alumni Weekly. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and SoundCloud. You can read transcripts of every episode on our website, paw.princeton.edu. Music for this podcast is licensed from Universal Production Music.

Paw in print

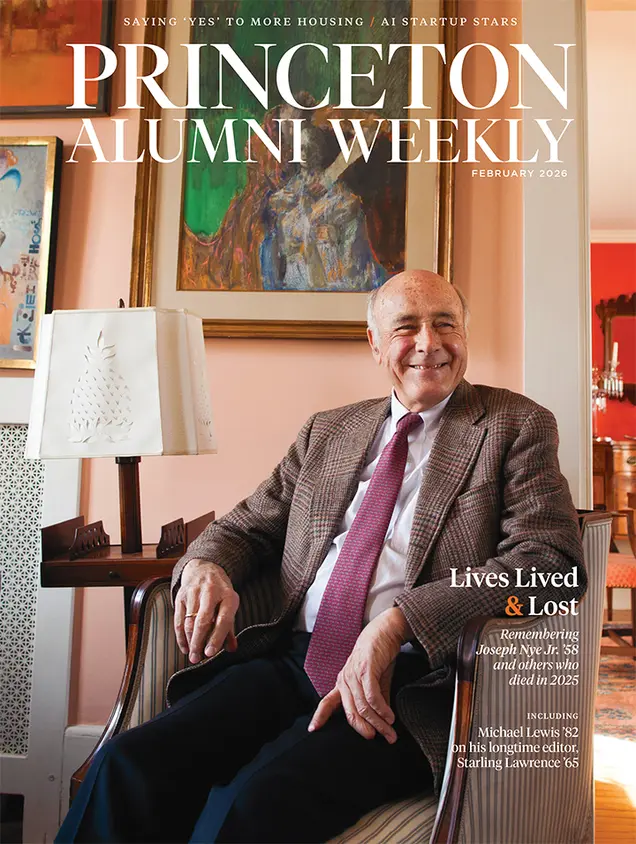

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

No responses yet