Remembering Richard Springs III ’64

Dick was ‘a philosophy major playing football, which always bemused our father enormously. Or maybe a football player

majoring in philosophy ... ’ — Lanny Springs ’64

Welcome to the PAW Memorials podcast, where we celebrate the lives of alumni. For this episode, PAW Memorials editor Nicholas DeVito sat down with Lanny Springs ’67 to discuss his brother Richard Springs III ’64. Dick played football at Princeton and was a cattle rancher.

Listen on Apple Podcasts •Spotify •Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT

Nicholas DeVito: Hello, this is Nicholas DeVito, Class Notes and Memorials editor for Princeton Alumni Weekly. Today we’re talking with Lanny Springs from the great Class of 1967. We’re going to discuss his brother, Dick Springs, from the great Class of 1964. Hi, Lanny. How are you today?

Lanny Springs: Nick, good morning. Thank you very much. This will be a pleasure to do.

ND: I’m really looking forward to discussing Dick here. His memorial stood out to me. Your family came from Princeton, you’re a Princetonian family. I believe your dad, your grandfather, can you just kind of touch upon who in your family has gone to Princeton?

LS: Yeah. Surely. Richard Springs, my brother was Richard Springs III. Richard Springs was a graduate of the Class of 1877. My grandfather, who would at this point would be whatever that makes him, 148. But he was the Class of ’77. He wrote a letter to his father, who was not named Richard, but he wrote a letter to his father that we all cherish having, talking about what he was learning at Princeton, and how much the experience was meaning to him.

My father was Class of 1940. The first experience my brother and I had was going back to, I believe, his reunion in 1954, I think, or possibly a football game in 1954, and then his 15th reunion in 1955. My father said to both of us, fairly, I think with tongue in cheek, but I was never sure, “You can go to any college you want to, but the only one I’m paying for is Princeton.”

Well, as it happened, both my brother and I wound up going to Princeton. I think even though he would every now and then despair and say, “So, this is all I get for $5,000?” Remember, it was the ’60s.

ND: Correct. Correct.

LS: We would all laugh and go, “Yeah, dad. That’s pretty much it.” I think, I don’t know whether it was watching the tailback whose name was Agnew in the Class of ’54, but Dick was a football player for Jake McCandless at Kent, the Kent School, where we both went. And of course, Mr. McCandless became Coach McCandless at Princeton while Dick was there.

Dick’s experience at Princeton was so ... The football experience for him was so formative, all the way from his first Blairstown to his final game. And as I tried to share a little bit in the memorial, the friendships that he made with his fellow football players were just so unbelievably strong.

I remember that part of it was going over to the house of Coach Caldwell’s widow, Lucy Caldwell, which was over by the Springdale golf course. On Sundays, you would meet tons of athletes, not all of them from football, but they would all come over and drop by Mrs. Caldwell’s house, and they’d watch a game on television, and all talk and whatever. There was a real melting pot there.

The friendships that he made among his fellow footballers were so strong, and he worked so hard to keep them alive and current, in all the years after Princeton. He would go see people. I mentioned that he’d organized a trip out to see Jim Rockenbach when he was in the late stages of his life, and he got a number of the other footballers to go out there and see Jim with him.

That was the way he looked at those friendships. They were strong, they were enduring, and they were unbreakable. They were literally for the rest of their lives, and his life, as long as he knew them.

ND: Right. Well, this metaphor might be somewhat overused a lot, but with football, you’re in training, you’re going into battle every week. I think that those bonds are unbreakable. I see that a lot with the sports teams. I think it’s amazing. You go through a lot. And so, they’re your other brothers, you know? So, that’s great that he worked to always keep the connection together, too.

Lanny Springs:

Yeah, I mean, he ate at the Tiger Inn. But I would say to you that his eating club was the football team.

ND: OK.

LS: Because it didn’t matter whether the season was in or out, those were the people and the bonds that he worked the hardest to maintain and keep strong. He succeeded, to a great extent. Because when we would talk, he lived three time zones away, as our lives turned out, I was East Coast, and he was on the West. But so often the conversation would fall back to this gentleman or the other that he had connected with in Florida, or Southern California, or someplace in between.

ND: Right. Yeah. And so, after Princeton, he was teaching in California for a couple years? And then he got into ...

LS: He did. He taught down in La Jolla, but one of the things, Nick, that I remember so vividly, was his going up to, I’m going to say maybe as a 13-year-old, he’s going up to Alaska, and working on one of those, I’m not sure what you call those little shuttles that you hand pump down the railway line, so that you can be fixing track when it gets broken.

But he spent a summer up there doing that. I knew when he came back from that, that he clearly was going to have an outdoors life. And the teaching I think was, I mean, he was a philosophy major, so it was no surprise that he would be interested in teaching. But I think he always had this hankering to be outdoors for a living.

ND: Right.

LS: He taught a couple of years in La Jolla, and then he moved up and started a cattle ranch for breeding cattle up in Oregon, on the west side of Oregon, up fairly near Eugene. And then when he found out how unsuitable the rainfall was for raising cattle, he moved over to the desert on the eastern edge of Oregon, western edge of Idaho. And he found that raising cattle in a desert environment, and it is considered a desert, was far more conducive to the cattle’s health.

It allowed him to be outside all his life. Hunting and fishing were always key pursuits for him and key diversions for him. And again, that was partially something he got from our father, who taught us both a lot about fishing and about hunting. Most importantly, an umbrella or a parenthesis around both of those pursuits, is respecting the outdoors, respecting nature.

ND: Right.

LS: I think this was key to him.

ND: Yeah. It’s interesting, because I grew up hunting with my dad and my brother. The first thing was, it was always respecting the environment and respecting the outdoors, because it provides. And so, you have to take care of it.

But for me, it’s interesting how your brother continued his love for it. And for me, I love being outdoors, but it wasn’t my calling. And so, I wonder how, if, as you got older, did you still have that outdoors calling you? Or was it particularly more just for Dick?

LS: Well, no. It was much more so for him. I’m much more, if he was country, I was definitely city. But that said, some of the best vacations, extended stays that I ever had, were with him and his family out on their ranch, first in Oregon and later on in Idaho.

Getting to hunt and fish with him when we were out there, were great connections and reminders of how much fun we’d had with our father growing up doing the same thing, because those were key pursuits of his. So, again, being three time zones different from each other, puts a little difficulty in getting together frequently.

ND: Right. Right.

LS: But those are some of the best memories I have. I can remember his teaching me, gosh, I was in my 20s at the time. Teaching me how properly to pick up a bale without throwing your back out when you’re dumping it from the truck out for the herd in the middle of, shall we say, cool weather in the middle of winter.

ND: Right, right.

LS: I mean, it really, the connection to the environment and he, later on, as I think I mentioned, he became a real proponent of farm-to-table. He called it locavore, which I think is an old-fashioned phrase at this point, because everybody says farm-to-table.

ND: Right.

LS: But he was a strong proponent of basically using the environment around you to help support you, so that you weren’t relying entirely on Safeway, or Piggly Wiggly, or whoever.

ND: Right. Right.

LS: These were core things for him, and he and his wife had tremendous satisfaction from being among the leaders of farm-to-table in their community.

ND: That’s great. So, did they have a restaurant, or they just worked with restaurants?

LS: No, no. They didn’t have a restaurant. They participated in a community center, where they would help organize the week’s provender, all kinds of contributed vegetables, and fruits, and be able to share them with the community. I think the community center basically sold them at cost to whoever wanted them. It was very, very satisfying for both of them.

ND: Yeah, that’s great. So, his philosophy and his wanting to give back and his outdoorsmanship, it’s all tied together.

LS: It is. It is.

ND: Yeah.

LS: But I need to go back and just tell you that, gosh, a week before his passing, he was sitting in his hospital bed. But one thing that was absolutely important to him, was participating in a Zoom call much like this, where he could contribute to the planning for a huge celebration, I believe it was last November, of the ’64, ’65, ’66 football teams.

I might have a detail in there slightly wrong, but the important thing is that at the age of 81, he couldn’t have been wanting to be any more connected to the Princeton football experience, to the point of making every conceivable effort to be part and parcel of the planning for whatever celebration there was.

I know that when he was recognized as one of the best football players, I think nothing in his life ever pleased him more than getting that recognition. Which he would’ve been the first to say, being the blocking back, it should’ve been somebody else’s, but the fact that he was recognized that way, was an incredibly rewarding satisfaction.

ND: Yeah. I know you had said, too, he was always participating in Princeton football reunions, and always just keeping everyone together. I think in the memorial, you mentioned that they started, it was 100 guys at Blairstown?

LS: They started with 130 guys, and I think they wound up with 13 that made it all the way through. And obviously those 13 shared a portion of brotherhood that really, nothing in the world was ever going to break.

ND: Right.

LS: Because when you go all the way from ... And again, in that day and time, Blairstown, I’m not even sure, I don’t believe freshmen got to go to Blairstown, because, of course, there was freshman football in those days.

ND: Right.

LS: But in your final three seasons, sophomore, junior, senior, Blairstown was an incredible launch not only to the season, but also to the sense of belonging to a team, that is what makes any good team, and there were some great ones back then, work.

ND: Yeah. Do you remember how long they are at Blairstown? I don’t remember.

LS: I think they’re at Blairstown for 10 days to two weeks.

ND: Yeah. OK. That’s what I was thinking. And that’s, to spend two weeks with a group, 24 hours a day, that’s how you build that team, you know?

LS: Right. Right.

ND: They carry that through their life.

LS: The coaches and the players, I mean, there was a bond there, as I mentioned. Coach Caldwell’s widow, hosting all of the footballers anytime basically they wanted to kind of just drop by her house. I mean, it wasn’t just the players. It really was the whole football ethic that Tiger Football had at that time.

It was utterly palpable to all of us who weren’t involved in football, and I was not a football player. But I was totally well aware through my brother, of how strong it was.

ND: Right. And so were, because you overlapped for one year at Princeton together, so you got to see a little bit of that while you were there with what he was, his friendship and his teammates.

LS: Absolutely. Yeah. I can remember, they lost the final game 22-21 to Dartmouth, which was a bitter pill to swallow, after an otherwise totally successful season. I think they wound up sharing the Ivy Championship because of that. I can remember going up to his suite before, like Thursday, or something like that, and he was going to be taking the bus up on Friday and just wishing him well. I think I said, “Break a leg,” or something theatrical like that.

Then he came back and was just totally deflated, because he knew they shouldn’t have lost the game. They did, and that’s the way life goes. And you might remember that, of course, that was a very strange end of season, because the assassination of President Kennedy had pushed the entire schedule back a week, so the football team had two weeks, to think about and prepare for the games, as did all the other teams in the league, because it got put back a week.

ND: Right. Right.

LS: But, yeah. It was a philosophy major playing football, always bemused our father enormously. Or maybe a football player majoring in philosophy, if you want to go the other way.

ND: Right.

LS: But that was a great source of an ironic grin that I can see on his face now. And then Dick, of course, goes into teaching, prior to winding up going into ranching. But the whole thing is connected. Because even as a rancher, he was always teaching, even later in life when he was doing food-to-table. Again, that’s another form of mentorship, if you will.

ND: Right, right. Yeah. No, that’s, to me, I’ve always, think outside the box a little bit. To me, it makes perfect sense. You want a philosophy person. You want someone to think about it, but, you want a good guy, a guy who’s going to be able to block, too, on the football team. So, I think it makes perfect sense.

LS: Well, and one of the things now, here’s a guy who I think at his peak weight probably weighed 175, 180. But one of the things he always enjoyed doing was hitting other people on hockey, which he played until he was 81. He was a defenseman. And he was still playing defenseman past the age of 80. Again, board checking and all is not not quite so allowed at master’s hockey as it is when you’re playing at the collegiate level.

ND: Right.

LS: But I always, always, admired the fact that here was a guy willing to throw 175 pounds or whatever, at objects that were considerably larger, and frequently meeting with success. His favorite memento was the picture that I think was in one of the sports sections of him blocking the end, so that Don McKay could get around the end and score the only touchdown when they beat Columbia, seven to six.

ND: Right. Which, I mean, seven to six in a football game is unheard of. So, to get that lone TD is...

LS: Right. Right.

ND: Yeah. No, that’s great.

LS: And Columbia, at that time, had an Archie Manning type quarterback, at least in terms of his celebration, named Archie Roberts.

ND: OK.

LS: He was the deal in the Ivy League. And to beat an Archie Roberts team was a pretty strong feather in your cap.

ND: Right, right. You had mentioned hockey. So, did he play hockey growing up, or it was just something ...

LS: He did. We were lucky enough to grow up with a pond available to us. I can remember going down at an early age and trying to learn to skate. My brother could skate forwards and backwards and every which way. And indeed, as I mentioned, was up in Canada a couple of times going to hockey camp.

I can fondly tell you that I’m lucky if I can even stand up on a pair of skates, much less actually move in one direction. Although I will say, having a brother as athletic as he was, was one of the reasons that past the age of 80, I’m still playing competitive squash four mornings a week.

It’s partly because of looking up at an older brother and seeing what he does that turns out to be successful. You try and keep the good stuff and follow up on it.

ND: Right. Right.

LS: But anyway, he was a very good skater. Loved playing defense. Loved checking people into the boards. That was a satisfaction that he got to pursue a lot longer than football.

ND: OK.

LS: Yeah. So, master’s hockey was another outlet that he greatly, greatly enjoyed. Again, here’s a surprise, played outdoors.

ND: Right.

LS: I just want to say, one vignette which has absolutely nothing to do with Princeton but gives you an idea of the kind of man he was. At the age of 5, maybe 6, I catch my finger in the car door. Now, I am soaking that finger all afternoon in Epsom salts or whatever.

It’s 1951. My 8-year-old hero brother sits down with me, a 5-year-old, and explains, watching a black and white Philco television, the intricacies of New York Giants baseball on television. OK? Now, to this day, it’s 75 years later, and I don’t know to this day, whether the fact that baseball is an absolute passion for me, and will be till the day I die, has more to do with how much he made me love baseball, or just the fact that my hero would spend three hours on a summer afternoon, inside, explaining it to his 5-year-old brother. OK?

ND: Right. The guy who ...

LS: You just sort of go, “Yep, the guy was teaching from an early age.”

ND: Yeah. No, that’s a great story. The guy who wanted to be outdoors the whole time, but he was taking care of his younger brother.

LS: Right. Lessons like that don’t need to be taught twice.

ND: Right. Right.

LS: I have shared that story with as many people as I can, and did at his memorial a few months back, because I would say that was one of the two or three most formative things that we shared in our entire lives.

ND: That’s great. I think that’s a great place to end it, unless there’s anything else you think we should share.

LS: There’s probably tons else, if I reach back into the recesses of memory and work hard on it. But I love leaving it with that, because that says a lot about how wonderful a man he was, even as a boy.

ND: It truly does. Lanny-

LS: Thanks for the opportunity, Nick.

ND: No, thank you for taking the time to talk about Dick. This was great. Thank you.

LS: Oh, you’re welcome. Take care.

ND: The PAW Memorials podcast is produced by Nicholas DeVito and Princeton Alumni Weekly. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and SoundCloud. You can read transcripts of every episode at paw.princeton.edu. Music for this podcast is licensed from Universal Production Music.

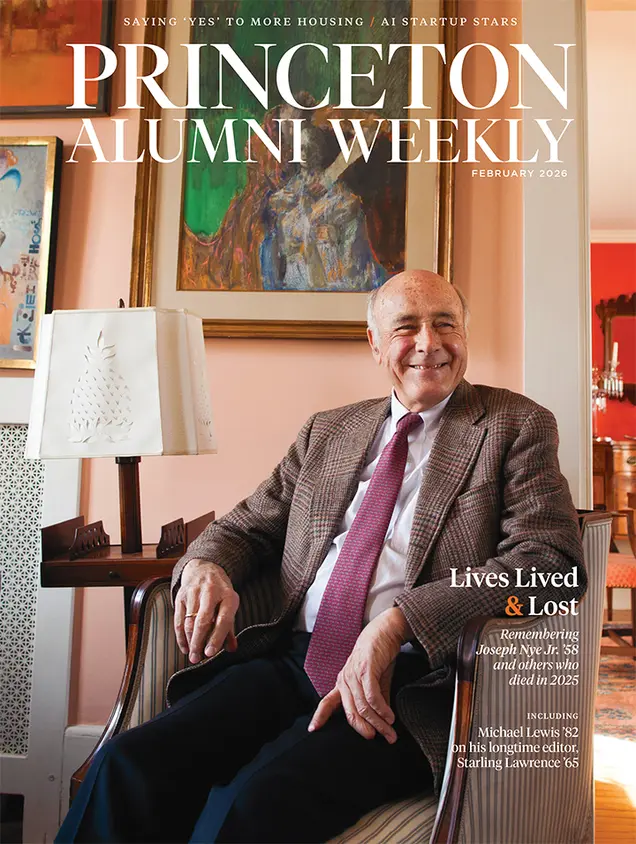

Paw in print

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

1 Response

Johnny O’Brien ’65

3 Months AgoThanks for Memorializing a Beloved Teammate and Brother

Thank you so much for unearthing unknown gems about your brother ... and our “brother,” Dick Springs. We were lucky to be teammates of his and loved him to death! You deeply captured that visceral, soul-centered bond that athletes (especially in contact sports) are prone to develop. But it went even deeper with Dick because of his constant, full-throated love of life, the sport, the environment … and us. Thanks for this gift.