Remembering Victor Brombert

“Brombert was very concerned that I talk about his love of teaching. He said, ‘My love isn’t war, it’s teaching and I hope you’ll find a place to mention that,’ which was a worthwhile admonition,” said Elyse Graham ’07

Welcome to the PAW Memorials podcast, where we celebrate the lives of alumni. For this episode, PAW Memorials editor Nicholas DeVito sat down with Elyse Graham ’07 to discuss Victor Brombert. He was a professor at Princeton. During World War II he trained with other young refugees from Europe at Camp Ritchie, a military training facility in Maryland, to learn methods of combat, interrogation, and lie detection.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT

Hello, I’m Nicholas DeVito, Class Notes and Memorials editor for Princeton Alumni Weekly. Today we’re talking with Elyse Graham from the Class of 2007, and we’re discussing Victor Brombert. Professor Brombert was a professor in the comparative literature department. He was beloved by many, and he died Nov. 26, 2024. The Princeton flag over East Pine flew at half staff in his memory.

Hello. Today we’re talking with Elyse Graham from the Class of 2007, and we’re talking about Professor Victor Brombert, who was a professor in the comparative literature department. And I’d like to welcome Elyse, and if you could introduce yourself.

Elyse Graham: Hi. I’m Elyse Graham. I’m a professor at Stony Brook University and as Nicholas said, a member of the great Class of ’07.

ND: Yes. And so back in October 2021, Elyse wrote a great PAW feature. Was it in 2021?

EG: It was 2021. I just forgot that 2021 wasn’t 2001. Don’t worry. I was like, that can’t be right. I was in high school. Go ahead.

ND: She wrote a great PAW feature about Victor Brombert and his life. And so he passed away Nov. 26, 2024. And so we thought he would be a great person for this podcast because he touched so many Princetonians. And so we thought what a great way to do a little tribute to him. So Elyse, can you tell us about the first time you connected with Professor Brombert?

EG: I was asked to write a piece about him for the Alumni Weekly because not only was he someone who was known for having a great career at Princeton, Princeton has a tradition of charismatic lecturers, and Brombert is certainly at the front of that field. But also, he had this other career before he came to Princeton that nobody had known about. His students hadn’t known about. Which is that he was one of the Richie Boys. He was part of this extraordinary group of largely Jewish refugees who worked in an espionage role during World War II and played an outsized part in helping to win the war. And he was featured in several documentaries on the subject and PAW thought that it was time to tell his story in its pages.

So, I had the pleasure of visiting his home. This was while ... Sorry, my dog is about to bark. All right. I had the pleasure of visiting his home. This was right after everybody got their first immunizations at the end of the pandemic. So, it was a pleasure to be able to visit him in person. And everybody was very fresh with the experience of seeing other people in person. Again, this is also the time the cicadas were out. Anyway, naturally, he was a wonderful interlocutor, and I wound up writing the piece.

ND: Yeah. It’s great. The Richie Boys, 60 Minutes did a documentary on them, correct?

EG: Yes.

ND: And that was before the PAW feature?

EG: Yes.

ND: But it wasn’t something he really discussed with his students.

EG: No. So his career in the war came as a surprise to his students. They were shocked to learn that the person who had been standing on the lecture stage talking to them about Victor Hugo and Flaubert and these other French authors also knew how to silently garrote a century from behind that he was trained in all of the dark arts of murder and deception and had applied them during the war.

ND: Yeah. So can you tell us a little bit about ... So, he was born overseas.

EG: That’s right. He grew up in Paris. His parents were Russian Jews who fled to Berlin to escape the Russian Revolution. And then when Berlin became hostile to Jews, they fled again to France. And things continued to heat up in Europe. His family went from one city to another in France trying to find a way out and ultimately made their way through Spain. At the time, this is around 1940, it was exceedingly difficult to get out of occupied Europe as a refugee. Partly because the Nazis were playing off of everybody’s expectations about what it means to have legal papers. You had to, in order to leave the country, have exit visas and travel visas and entry visas and other hard to get documentation that all had to be unexpired at the same time. But also the bureaucracy was extremely good at saying, “Oh, we’ll just process your papers if you wait here in Marseilles or whatever. And then once you have the papers, you can leave.” And they would just never process the papers.

So, the refugees who were waiting to get out would be kept from panicking. Even though they were headed to the death camps. The people who weren’t in any danger from the government could say, “Oh, well everything is happening perfectly legally. These guys will get their papers. The government has said so.” They didn’t need to ask hard questions about the regime that they were living under because there was a pretense of legality.

Anyway, at the last possible minute, Brombert’s family managed to assemble the necessary papers to go to America. In his memoir, Brombert says that his father did some illegal work, although he never figured out exactly what it was in order to get the papers and in order to get the money necessary at I think $10,000 a head in today’s money to board a ship that normally held 15 people along with a cargo of bananas. And held 12,000 people, 12,000 refugees when it crossed the ocean. So, the person who was running this ship made a profit of $12 million in today’s money by taking these refugees across at this exorbitant price.

But anyway, it was called the floating concentration camp when it arrived in New York because of the horrible living conditions and the onboard deaths from typhus and starvation. But his family did make it across. They were welcomed by some family friends, one of whom took them ... One of their first sightseeing excursions in the new country, he took them to Princeton. He thought this place was ... This is America. This sunny place with these charming shops, people walking around, carrying books, looking at every age distinctly youthful. This is America. The person who took them there pointed at Nassau Hall and said, “That’s where Einstein teaches.” Now, Einstein did give lectures at the University. He was at the Institute for Advanced Study, not the University itself, but Princeton has always been very pleased to claim Einstein as one of its own. So, we’ll pass over. That’s perfectly fine and well.

But he said afterwards ... And I want to pull something up. “Regardless of the misinformation, the brief stopover in front of Nassau Hall made a lasting impression on me. So, this was an American university. This was what I had heard about during the slow crossing on the ship. I took it all in. The ivy-covered stone building, the tall trees, the expanse of green, the carefree young people who seemed to be ambling in a vacation atmosphere. Students and teachers such as I had never encountered in the gray environment to French academe. These fleeting autumnal impressions later accompanied me during my Army training and then occasionally re-emerged during the campaigns in France and Germany until one late summer day of 1945 in devastated Berlin, they came back to me in a flash. Only this time the image included me.” At the end of the war, he suddenly remembered Princeton and he thought, “You know what? I want to be a student, and I want to be a professor. I want that to be my life.” And he achieved it. He eventually came back to Princeton himself, and he used to call it his fate of Princeton. The idea that one way or another, he was always going to return if he survived the war.

ND: Right. So, before he was at Princeton, he was at a different school.

EG: University of a kind. Yes. So, the United States entered the war. He joined the military right away. He had been hoping ... When I say he had been hoping, he had been hoping for an opportunity to go back to Europe with an army behind him. He had been raised by pacifists, but by the time the United States entered the war, his parents understood as he said, that this was a war that had to be fought even though it had to be fought and won by people who hated war. He joins the military. He trained for the Medical Corps, but he was a refugee. He could speak multiple languages, German, French. And someone in the Pentagon ... This is his writing again. Had the bright idea that these foreign types in American uniform could be put to a different use. They spoke other languages. They had lived in other countries; therefore, they must have insights into the mentalities of those we fought or liberated. And so quite a few of us were sent to Camp Ritchie for training in military intelligence.

So Camp Ritchie was in western Maryland. The English had these spy training schools that were incredibly posh. They had been doing this for a while. So, their schools were in country manors that had housemasters and servants and that sort of thing. The Americans had camps with tents in national parks. So, it was a bit of a different experience, but that was terrain that could support combat exercises as well as enough seclusion to keep the goings on secret. The English also sent over their fighting instructors to teach the American spies how to fight. So you as a fresh-faced recruit, as a spy in training, would be learning how to do the close combat that leaves the other person, not injured, but dead. So Camp Ritchie ... Hold on a second. There have been a few wonderful books written on Camp Ritchie. One of them is by Beverly Driver Eddy, another is by Bruce Henderson. And Henderson says that the largest group of graduates from Camp Ritchie that is training these speakers of foreign languages how to do espionage in the war, the largest group of graduates was 1,985 German-born Jews trained to interrogate German POWs. So, this is very much a body of the people Hitler despised and tried to destroy coming back and hitting him very hard.

ND: Yeah.

EG: So Camp Ritchie trained people in what’s called combat intelligence. This is tactical, not strategic, meaning this is about what we do next, not what we do a month from now. It’s of immense importance. These speakers of French and German and other European languages we’re going to travel with the front lines and interrogate civilians or prisoners of war about the combat zone ahead. Do we turn right or left? Are there German soldiers ahead? If so, what are they armed with? That sort of thing. And they were also trained to do reconnaissance work ahead of the front lines. Their training involved a lot more than interrogation.

In his classes Brombert learned at Camp Richie, which he later called his first university, he learned the specifics of how to interrogate civilians, how to interrogate prisoners of war, how to liaise with members of La Résistance. But he also memorized the hierarchy of the German and Italian armies. He the insignia on their uniforms, the look and capabilities of their cars and tanks and guns. He learned how to read aerial photographs, how to do reconnaissance in the field, how to make sense of documents that have been captured from the front. He learned Morse Code. He learned how to find his way around at night in unfamiliar terrain. He learned how to kill someone silently by using a stick to garrotte them from behind. And during that 60 Minutes documentary, he very casually explains how to silently garrotte a sentry.

Camp Richie was one of the most important of dozens of secret training facilities across the United States during the war. He says later on, it was his first university, not just because of the things that he learned there as a spy, but because many of his fellow trainees who were lawyers, professors, musicians, had advanced degrees. And so during downtime, he would listen to them chat about Mozart and about architecture and this sort of thing. He later said, “It’s important that we have peace and food, however, the ultimate question is what we do when we have peace and fill bellies.” He says, “The humanities are not so concerned with physical survival as with the very notion of survival.” So, there’s something else that he’s getting at Camp Richie. He’s learning how to survive in a very-

ND: That’s beautiful. Yeah.

EG: Yeah. But also why we survive, what we survive for, what we’re trying to keep alive. So, all right. Let’s see. And the other thing to mention is this. He says, “The training. The training for interrogation, but above all, the actual interrogation of prisoners required interpretation because you had to evaluate what they were saying. You had to learn how to read between the lines. You had to learn how to listen between the lines.” So this was also his first training in rhetoric because basically all of the Camp Richie experience and interrogation is based on words. “So you had to be keenly sensitive,” he said, “not only to what people said, but how they said it.” Now, bear in mind that he comes back after the war and becomes a professor of comparative literature. That is, he takes his training in reading between the lines, his training in hearing between the words and this becomes the basis of his post-war career. Let’s see. So almost as an aside, I want to say that his career demonstrates the importance of the humanities, not just-

ND: Right.

EG: Also because he was working in tactical combat intelligence. The people a generation older than him, professors, including professors from Princeton, were working in intelligence in a field called research and analysis. So, they were sitting in the New York Public Library or in the basement of the Library of Congress, and they’re going over documents that have been sent home from Europe and coming up with strategic intelligence, that is what we do next month instead of what we do right now. And they were trained in the humanities and social sciences. That’s precisely why they were recruited to work as intelligence analysts. What gave those fields of study value for intelligence is that they specialize in examining evidence and making informed judgments in cases where data is poor and evidence is ambiguous. A war isn’t a controlled experiment. So these professors who had training in the humanities were very good at working with the kinds of ambiguous data that come up in a war making strategic intelligence estimates that were unprovable, but still very smart. You can cut that part out if you like, but I’m very passionate about the value of the humanities.

ND: No. Me too.

EG: Particularly because Princeton is going to be one of the last schools to continue teaching it. All right. Brombert became a citizen Sept. 9, 1943. Shortly afterwards, he was put on a ship to England. Now he was a young man. He later said, when I was talking with him, “Almost petulantly, I wanted to liberate France.” This is a young man’s dreams.

ND: Right. Right.

EG: And that’s not not admirable know, although there’s an element of naivete to it that he-

ND: 100%. It propelled him to keep going forward.

EG: Exactly. So, he says in his memoir, on that ship, standing on the deck near the railing, looking out at the other ships and at the angry winter sea, I indulged in silly talk about fighting, liberating, heroic action, and the noble side of military servitude. And the older officer who was listening to him gave him a chilly look and said, [foreign language] which means you have the virus.

Brombert is part of the Normandy invasion. He lands two days after D-Day. It was shortly after that that he was cured of [foreign language]. Although he wasn’t sure whether it was shortly after D-Day when he lay all night on the bluff above Omaha Beach too tired to dig a foxhole with bullets screaming overhead at him imagining at every moment that one of them would hit him, whether he was later on pushing through a German forest in an extremely dangerous operation, where a lot of people died for no good reason, but he lost it one way or another. He survived. And the lesson that he took from that was this. He said, “From that point on, I kept telling myself, let’s win the war but without loving it.” He keeps going. He hauls himself through the work of pushing back enemy forces and interrogating civilians. The purpose of interrogation, as I said, was to gather simple, concrete, tactical details. How many men were ahead and where and with what kinds of weapons. Witnesses could be misleading either accidentally or on purpose. So he remembered one French woman who said, “Don’t go to the right. There’s danger on the right.” And she points to the left and he had to figure out, “All right. Is she lying to me?”

But look, Normandy was the turning point. The Allies were really gaining traction in the war. He actually snuck into Paris during the liberation of that city. He felt he deserved it by then, which he did. The Germans had retreated and for the sake of French pride, French military units were supposed to liberate Paris. Brombert was wearing an American uniform, but he snuck in. And he was particularly eager to see his old girlfriend who had lived in Paris, Dany Wolf. And so he thought he would show up at her door wearing an American uniform. It would be this moment. He finds her apartment, he knocks at the door and a woman he doesn’t recognize opens it. And he asks about where Dany is. And it’s just a single word that comes back. [foreign language]. And he understood what that meant, which was that she had been sent to one of the camps, although he did not understand fully, very few people understood fully what was happening in the camps, but he knew that it was a death sentence. And in fact, Dany Wolf was murdered in Auschwitz.

The war ends. He winds up for a while, I think in Berlin, and he is assigned to ... Give me a second. The war finally ends. He winds up working with a denazification task force in Germany. So he’s reading and annotating everything he can find about the Nazis’ rise to power. He’s also interrogating prisoners of war. And there’s one instance that he describes in his memoir with more shame than I think is actually warranted, which is he lost his temper while he was interrogating a Nazi official and started yanking him around by his beard and shouting at him, did you know about the camps? Did you know about the camps? And Brombert thought that that was a poor moment for him. I think it was ok.

ND: Yeah. Like you said, no one really knew what was fully going on. And then I’m sure once he found out it was the devastation.

EG: Yes. Yeah. Very much.

ND: I think that’s warranted.

EG: But he was very tired by then. He was exhausted with everything that he had learned during the war about politics and about human character, the way that French civilians would condemn their neighbors as collaborators, but excuse themselves. The way German civilians would refuse to condemn anybody or talk at all about what had happened. The way the Americans often left Nazi officials in place in the name of keeping the engines of the German state running. So this is the time when he remembers Princeton and he thinks, I’m going to be a student. I’m going to be a professor. So, he returns to the United States. He does enroll as an undergraduate at Yale University, although in his defense, he just happened to be on a train and got off on an impulse in New Haven. So that was accidental. If he’d had time to really think it over naturally, then-

ND: If he stayed on the train another hour or so, he would’ve.

EG: Exactly. Exactly. So, he did something that happens at Yale, which is he studied at Yale as an undergraduate and then I think as a graduate student and then remains there on the faculty. And then 20 years later he thinks better of it. And he leaves Yale’s faculty to teach at Princeton. And I have heard from insiders at Yale that it was a scandal. A bit of a scandal when he left Yale to go to Princeton because he was, I think in Yale’s French department, which was very famous, very prominent. It was supposed to be the very best place that you could study French literature. And for him to leave and to go to Princeton, they couldn’t figure out what he was thinking. But I think you and I understand.

ND: I think we understand. I think our listeners understand as well. Yes.

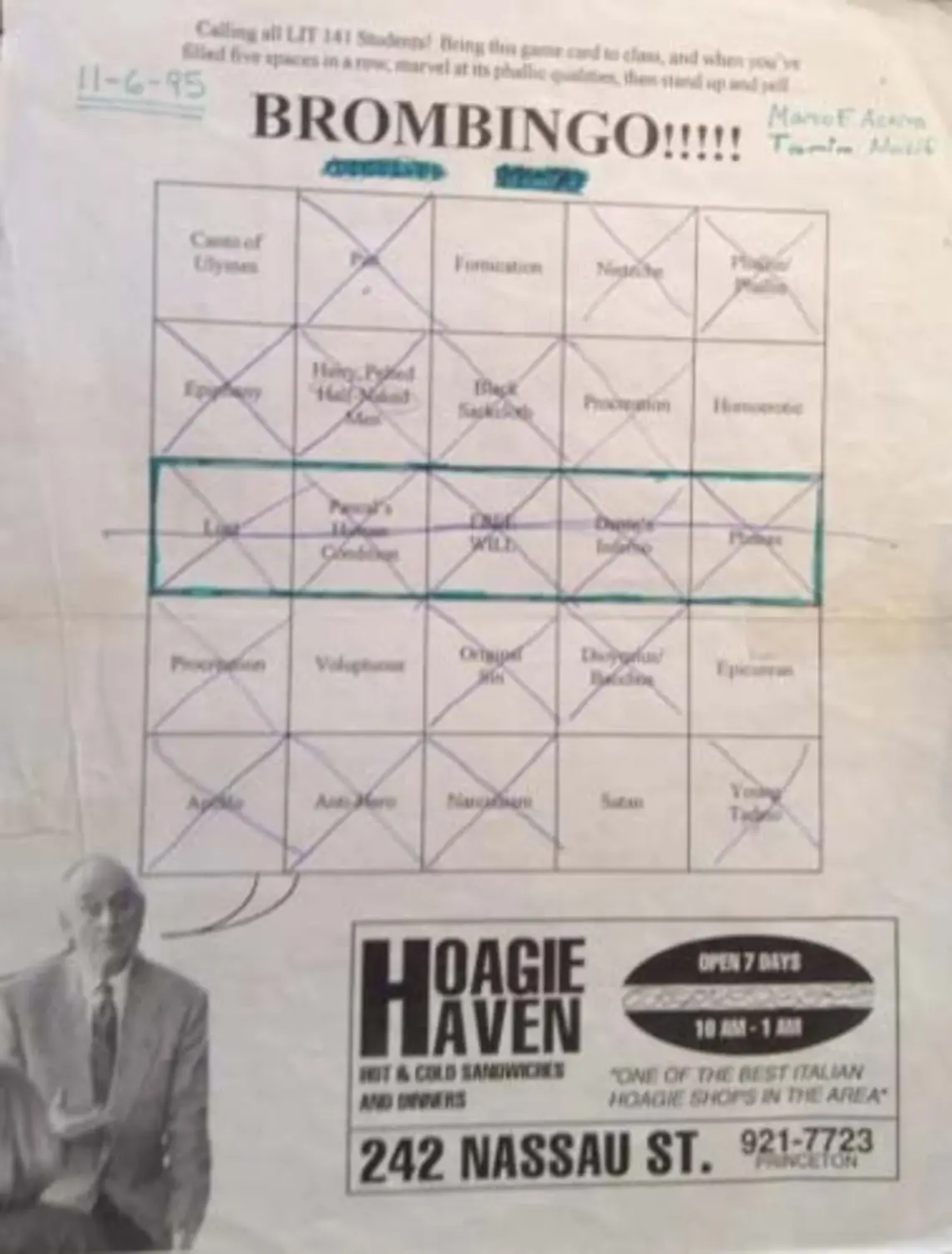

EG: That’s right. So look, Princeton isn’t the historical teaching home of Albert Einstein, but it is the historical teaching home of Victor Brombert. He becomes a beloved professor of romance and comparative literature, and he lends a tone and a sensibility to the department that can be felt to this day. He becomes a very beloved teacher. He said, “I loved every moment of my teaching profession. I liked the small seminars, I liked the discussion classes, I liked the large lectures. But what I liked most of all, I think what gave me the greatest satisfactions also of a histrionic nature, is the large lecture course I had for a freshman class in European literature. I had between 300 and 400 students every year.” He was very famous among the students. Once in 1994 while he was giving a lecture on Virginia Woolf in this class, A student stands up in the balcony seat and shouts “BromBingo” because the campus humor magazine has put out a bingo card that lists all of Victor Brombert’s pet topics and students were crossing them off. He was very moved by this. He said, “This kind of teaching is a sign of playfulness, the ludic element, which should always be at the heart of learning and teaching, because playing with ideas is never a frivolous activity. It’s when we’re at our best.” Yeah. He really enjoyed himself at Princeton and he left something to Princeton, which is marvelous.

ND: Yeah. I find that so amazing that he had such an impact on the department, that they’re still referencing him and how he was and how he taught to this day.

EG: Absolutely. And one of the things that remained ... Look, he retired before I studied at Princeton, but I took classes in the department of comparative literature, and it has a philosophy that involves a sense of irony. A philosophy that involves teaching and writing and thinking about irony as a way to embrace cultural multiplicity and avoid the dangers or resist the dangers of ideological absolutes. A irony that doesn’t put people down or cut, but that’s very generous, very kind. I took classes in the department of comparative literature when I was at Princeton, and this is after Victor Brombert retired. But one of the characteristic elements of the department of comparative literature is a philosophy that takes irony very seriously as a way to embrace cultural multiplicity, to resist the dangers of ideological absolutes, to think something through from multiple angles at the same time. A irony that’s very, very generous. That doesn’t cut or put people down. That’s very kind. And professors in the comparative literature department, when I spoke to them, attributed this to Victor Brombert. They said this is part of the tone, part of the style that he left to the department. And he was delighted when I mentioned this to him. He says, “This is one reason I like not the irony of a Voltaire, which is very cutting, but the irony of a Stendhal. It’s marvelous. It’s marvelous. And it is an irony that goes together with tenderness. Mozart is that way. The operas of Mozart, the marriage of Figaro. I’m very moved by what Maria Di Battista has said.” When students are tired of studying the text, they will occupy themselves with studying the professor. And this is one of the things that he gave to the University. This philosophy, this posture, this way of being in the world that I think resides as part of the tone of the University to this day.

ND: Yeah. That’s so profound. It’s true. Yeah. Wow. Is there anything else that you had learned while researching him or writing about him that did not get into the article or that we haven’t discussed that you want to share?

EG: I can give maybe another line about his philosophy of teaching, which he says, “I don’t believe in teaching ex cathedra, in being doctrinaire, in lecturing at people. The hours of teaching are confrontation, a time to make discoveries.” I told you that Princeton has a tradition of charismatic lecturers, and this is true, but one of the things that made a lecturer like Victor Brombert so beloved by his students is that he wasn’t reading from the proverbial yellowing lecture notes. He was always, even at ... I say even at his age, as though we’re not both rapidly hurtling in direction.

ND: Yeah. Yeah.

EG: But still discovering new things. Still taking pleasure in discoveries and sharing that sense of discovery with his students.

ND: Right. Forever the student.

EG: Yeah. That’s exactly right.

ND: Yeah. Yeah.

EG: So look, one other thing that’s not quite Brombert, but let me ... Hold on a second. Just for your amusement.

ND: Yes.

EG: All right. As an aside, I said he trained at Camp Richie. Irving Press, the son of the founder of J. Press, and later the head of that company worked at Camp Richie, which actually wound up influencing the direction of J. Press after the war. And the war is also the reason that Princeton is a Brooks Brothers school instead of a J. Press school. All which is more or less irrelevant, but the war thoroughly influenced post-war Ivy League schools from the clothes to the teaching since all of the older teachers were spies in the war. And then the younger teachers had fought in the war. And then people like Victor Brombert had done both.

Post-war universities were not just concerned with how to survive in a material sense, but what we’re surviving for. And I think the impulse for that certainly came from the wartime experiences of those generations of professors. This year is the 80th anniversary of their victory in World War II. And it’s a good year to consider the legacy that was left to us by people like Victor Brombert and to think about how to keep the things that he loved alive, even as new kinds of crises overtake us.

ND: And why do we fight the good fight? What are we fighting for if we’re not fighting just to fight? We’re fighting for things that matter.

EG: Right. Supposing that a war we’re fighting is a war worth fighting and being won by people who detest war. If they detest war, what is it that they love?

ND: And that’s the key piece right there, is that the war was fought by people who didn’t like war, but they knew what they were fighting for. They were fighting for the bigger issue. And yeah. 80 years.

EG: When I went to interview him, he was very concerned that I talk about his love of teaching. He said, my love isn’t war, it’s teaching and I hope you’ll find a place to mention that, which was what a worthwhile admonition. One falls so easily into stories about wartime heroics.

ND: Right. And that was just a small part of his life, which-

EG: That’s right.

ND: Pushed him to this great teaching career. Yeah. But you’re right. We want to focus on the war and how they got through it, but it was a few years at the end of the day where he taught much longer and influenced so many more people.

EG: War puts us in stories that are outside of our control. Before the war, he thought he might be an opera singer and he was kicked out of that. I think you can’t train to be an opera singer any more by the time you’ve ... I think he was a little too old for it by the time the war finished. But he did sing opera as he walked across campus. He was somewhat famous for it just to himself. And the life that he did choose for himself when he was able to choose a life for himself was a life of teaching. He was one of Princeton’s great teachers, and he’ll be remembered for that.

ND: That’s great. Elyse, I think we should end it right there on his wonderful teaching career. I want to thank you for taking the time to speak with us about Professor Victor Brombert. Thank you.

EG: Thank you.

ND: The PAW Memorials podcast is produced by Princeton Alumni Weekly. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and SoundCloud. You can read transcripts of every episode at paw.princeton.edu. Music for this podcast is licensed from Universal Production Music.

Paw in print

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

No responses yet