Stephen Lamberton ’99 Is Destigmatizing Suicide by Telling His Story

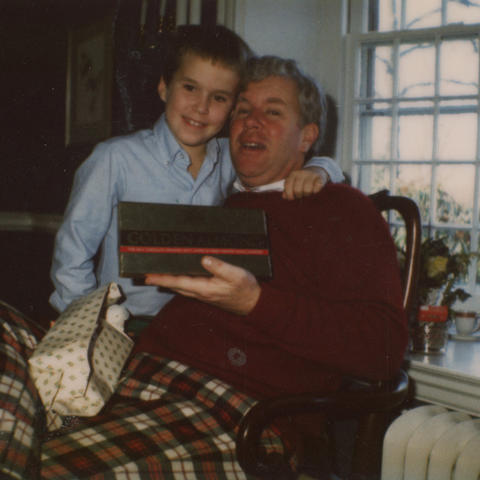

As a volunteer with the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, Lamberton is sharing the story of his father’s death in 1985

As a volunteer with the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, Stephen Lamberton ’99 is sharing the story of his father’s death in 1985 in hopes of destigmatizing suicide and helping others struggling with the loss of a loved one. On this episode of the PAWcast, Lamberton describes his journey toward processing his father’s death and discussing it with his own children, as well as the meaningful experience of attending his 25th Princeton reunion — an experience that his father, who also attended Princeton, didn’t live to see.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT

I’m Liz Daugherty, and this is the Princeton Alumni Weekly’s PAWcast, where we talk with Princetonians about what’s happening on campus and beyond.

Today I have the privilege of speaking with Stephen Lamberton from the Class of ’99 who reached out to PAW with a story he’s trying to share: that of his father’s death by suicide in 1985, and of the long journey Stephen took to realize that talking about it could help him heal and also help others who might be struggling with mental health or with the loss of their own loved ones.

Today Stephen works with the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, and he said that attending his 25th reunion last year at Princeton, where his father, Robert E. Lamberton, graduated with the Class of 1966, was profound.

Stephen, thank you so much for reaching out and for coming here to speak with me today. Before we get started, I’d like to take a moment to mention that listeners of this podcast will be hearing about some difficult topics. If you or anyone else you know needs help, you can reach the Suicide and Crisis Hotline by dialing 988, and you can text the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741.

Stephen, thank you so much for being here today and for making the trip. I really appreciate it.

SL: Thank you. It’s great to be back on campus any opportunity I get.

LD: I’d like to start with your decision to talk about this. So what are you hoping people take away from hearing your story?

SL: Yeah, I think you touched on it a little bit in the intro, just that talking about it is helpful. So I think destigmatizing suicide, sharing with people that this is something that’s happened to people and they can talk about, and also being a little bit vulnerable and showing people that it’s OK to be vulnerable.

The example I like to use is I had the good fortune of going to a summer camp when I was a kid. It was a very boys summer camp, very heavy on sports. But one of the things they did is they had a musical at the end of the summer, an operetta by Gilbert and Sullivan, was the name of the people who wrote a series of operettas. And one thing that I noticed was that there was a very prominent adult counselor there who was a former NFL player, a very-larger-than-life figure, but he always was in the operetta playing a woman. And it never really occurred to me as a kid, but then I really saw that he was basically saying, hey, if I can do this, if I can be vulnerable, if I can get on stage and play a woman, that kind of takes the cover off that no one else has an excuse not to do that. So that’s kind of a framework I use for my own vulnerability, which is, if I can be very vulnerable, then it shows people that they can be vulnerable about things, too. So that’s a big part of the reason sharing this kind of stuff is so important to me.

And then it sort of gets to my story. So what is my story? The beginning of my story, as you said, is my father died by suicide in 1985 when I was 8 years old. The now of my story is I’m almost 48 years old, a father of four, a husband, a professional, a volunteer with AFSP, and someone who’s a suicide loss survivor. But I’ve kind of reckoned through the middle of my story, which we’ll talk a little bit more about, because that’s what I was here.

I’ve reckoned with what that means to be a suicide loss survivor, and noticed that my father’s death by suicide was the impact of a mental health outcome that was not treated. And so in that way, and this has been part of my process, his death by suicide is not that different, at 41, is not that different than my wife’s, and this is something we deal with our kids, my wife’s mother’s death from cancer at 67. They both had a health problem, there was a variety of factors — their health, society, their family, the health-care system, the history of scientific breakthroughs that led to them dying from that cause. And so for us now, at the now part of our life, those things aren’t that different.

My father’s death was the result of a health outcome, but being able to have that perspective on it has been very helpful for me and it’s taken a while. Now at the time when they died, his death at 41 was different than my mother-in-law’s death at 67. She was younger, her children were younger, or rather, my father was younger, his children were younger, his parents were still alive. So that’s very different. But now, looking back on it, it doesn’t have to be thought of as different. And a bunch of the stigma that attaches to death by suicide doesn’t need to be there, sitting here now at the presence of my story.

So sharing that — first of all, it’s very helpful for me to share the story, but I hope that people will start to have a realization and an understanding for suicide, and that destigmatizes it, and makes it easier to understand and talk about.

LD: So you were 8 years old when your father died. I think very fortunately for all of us, the national conversation about suicide has changed a lot. Did you work with a therapist when you were a kid? Did you later? Was that part of your kind of journey working through all of this?

SL: Yeah, I think you’re right, the national conversation has changed, but I think you actually have to start a level higher. I think if you think about grief as a topic, I think the national conversation around grief has changed a lot.

One of the things I do, I work as a facilitator at a bereavement center that has a support group for teens who’ve lost a parent or a sibling through any kind of death. And so I think there’s a lot more organizations like that, and there’s a lot more awareness that grief is a thing that needs to be nurtured and people need help with it. The organization I volunteer with in Westchester County, New York, where I live, it was started in 1995. So by definition, it would not have been available to me when I was age-eligible for it. I graduated from high school in 1995.

So I think you’re right, and I think we need to start a level higher, that the conversation around grief has changed a lot in our lifetimes, and then also suicide. So the AFSP where I volunteer, that was founded in 1987, so that was two years after my father died. So there was no organization like that in 1985 when my father died, and there wouldn’t be for two more years. And they’re doing a bunch on research, education, advocacy, to really change the conversation. And one example I’ll give is you’ve heard me say, and you’ve used, death by suicide or die by suicide as opposed to committed suicide, and that’s a small thing. But the point of that is kind of take the culpability out of it and just have it be the way that the person died.

And I learned about that recently in my training with the bereavement center, and I wasn’t that sure about it, because I was still in the middle of my story where I was like, well, no, my father did this. I still had those feelings, but I was sitting in training, so I couldn’t very well not use the language they were telling me to use. And it was really the practice of using the language that kind of helped me on this path to seeing, it’s not something he did, it’s not certainly something he did to us, it was the way he died and it was the result of a health outcome. So I think that was very important.

In terms of my own journey and therapy, I have a memory of being in therapists’ offices as a kid, I can picture three distinct offices I think I was in as a child, but there was no continuity of that. And really the first memory I have of speaking to someone about this was when I got engaged. I was fortunate enough to meet my now-wife who was also a member of the Class of 1999, Heather Daley, now Heather Daley Lamberton, shout out. And so when we got engaged, we decided to have the officiant of our wedding be the reverend and the head of the religion department at her high school. So we had kind of a Pre-Cana, very light, to where we went in and met with him.

And he asked about my parents, I shared how my father had died. And from my perspective, this is where I was at that point in the middle of my story, I felt like he just then was on me. And I experienced what was obviously very good-natured and probably very appropriate asking me about that as very accusatorial, and really I viewed it as like, “OK, this guy knows Heather, he’s meeting me and he’s pointing out all the things that are wrong with me.” And so my stance to therapy at that part of my life was, I viewed any questions or kind of engagement with how my father died as really accusatorial, and so it was very hard for me. So I did not have therapy. I’ve had more therapy in the last three years than I had in the 37 years following my father’s death until then. So it’s been a big part of my process what’s gotten me to kind of the now of my story. But in the middle of my story, in the time I was here, I had not really had any therapy.

LD: So what was the most important thing for you in terms of your growth and your kind of coming to grips with this, and your healing from what happened? What made the difference for you?

SL: Yeah. So you and I talked a little bit about an essay that I wrote for the AFSP. And really the reason I chose to write that essay, I wrote the essay about the process and the decision to tell my children how their grandfather died. And really the reason I chose that thing to write about was that was kind of the inflection point for me in my process. And I think about that, of going from the middle of my story to the now of my story, we’re in now now.

So I had a perspective, when I first had children, that I wasn’t going to tell them about how their grandfather died. And really because, first of all, I didn’t like talking about it with anyone, and I had a fear, I didn’t kind of know the word ideation or something like that, but I felt like if they knew someone in their family had died by suicide, that they’d somehow be more likely to die by suicide. And so much like I did in other parts of my life, I avoided talking about it with them.

Now, that didn’t mean that it didn’t come up and wasn’t a factor, because it very much was. It sort of impacted the way I interacted with them. And it wasn’t until my son, so I have two older daughters and I have two younger sons, I have four children. Until my older son was 8, which was like three years ago, which was the age I was when my father died, that I was like, whoa, OK, that was the age I was when my father died, that is very young. And so I started having a lot more feelings about that, feelings both of pride, but of less things, I was sort of proud that I was a father to them that I hadn’t had, and that made me feel good about myself, but it also at times made me resent them, because they would do perfectly normal things and I would react to it with a little bit of “how dare you not be more grateful because you have a father and I didn’t.”

So one kind of example I give is I like making breakfast for my children. It’s kind of a very easy manifestation of caring for them. And so oftentimes on the weekends I’ll make pancakes for them. And I call this kind of a pancake paradox. It would happen frequently that I would make them breakfast, they didn’t ask for it, it was something I felt I was happy to do, but then they wouldn’t get to the table in time, or they wouldn’t clean up in time, or they wouldn’t set the table, and I would get mad at them because I was kind of resentful, because in the back of my head I was saying, “how dare you not be more grateful for this when you have a father doing this for you and I didn’t have a father,” which is, like, a lot. They didn’t ask me to do this, and their behavior was not ... It could have been better, but it was well within the realm of normal and acceptable, and my behavior was not.

And so it was really examining that that I came to the realization that I thought I was shielding them from something by not sharing about my father, but really it just was building up this resentment, and so that led to the process of telling them. And that really was the inflection point of my coming to grips with this more. I obviously worked with a therapist on this, but that was a big part of my sort of the change and has gotten me where I am now, where I feel like is the now part of my story as opposed to the middle kind of unprocessed, unresolved part of my story.

LD: So now you attended Princeton just like your dad. Was that what made you want to come here?

SL: Yeah. So first I’ll say, anyone who has a college decision still in front of them and you have the opportunity to go to Princeton, this is not a nuanced or hard decision, go to Princeton. As the saying goes, it is the best damn place of all, come here. So there doesn’t need to be a lot of nuance to that. But again, I was in the middle of my story at that time in high school when I made that decision, and my father’s death was just completely unprocessed. I have a memory of someone telling me that I shouldn’t let my father’s death define me. And the way that I interpreted that, I now realize, was I should tie it in a bow and either pretend like it never happened or pretend like it happened in the past and was irrelevant.

And the example I now give, as I’ve thought through this, it’s as if I lived in a house and in some corner of the house there was a lava pit of doom, that if you stepped on it, you would die, and someone said, don’t let the lava pit of doom define you. And so there’s two interpretations of that. You could never go in the room with the lava pit, eventually avoid the whole section of the house, never invite anyone over to your house, and eventually move out of the house, and you have not let the lava pit of doom define you, because they’ve not killed you. Or you could study the lava pit of doom, learn everything you could about it, so that you can interact with it with ease, and know exactly what it was going to do and be safe from it. And it wouldn’t have defined you then, you would’ve processed it and you could manage it. And so that’s what my father’s death was to me: It was completely unprocessed, and I just sort of avoided it and tied it in a bow.

One of the things about losing a loved one that young, I don’t know if I remember that my father went to Princeton, or I remember remembering. I have a vague recollection of maybe going to a football game. He was in Colonial and sort of walking from Colonial down Roper Lane to the football stadium. But I’ve now done that so many times that I don’t know if I’m remembering remembering, but I sort of knew that he went here. We got the PAW, as I said, in my house my whole life. So that was kind of like a tether and a connection. I can remember his 25th reunion book, which is a book that comes with bios of everyone, and we did it now for our 25th online. And I also grew up in Philadelphia, so there was Princeton people around, so I sort of remember remembering.

But again, it was totally unprocessed, his death. So it’s not like I was able to say, “oh, my father went here, I know what that means to me, I have a clear understanding of what he is to me, and he went to Princeton, and so that’s important to me and I’m going to do that.” It was all very clouded and unprocessed. So yeah, I’d love to be able to say I had a clear recollection of it, but it was just all part of this middle of my story where everything was unprocessed and unresolved.

LD: So once you were here, what was your Princeton experience like?

SL: Yeah, again, similar again, we’re in the middle of the story. And so relative to my father, it’s interesting to me that I have no recollection ever of being like, oh, I’m here on campus, I wonder if my father walked on this same walk or had a class in this room, or anything like that. It was as if I was inhabiting a space that he had never inhabited. I had no ability to draw on that.

I would say that the other thing in my college life, I think not dissimilar to a lot of people at Princeton, I had a real what I’d call imposter syndrome, which is I know not rare here, because there are so many accomplished students and people feel imposter syndrome, but mine was specific to me.

So one of the things I’ve learned that I’ve dealt with in this kind of middle part of my life, and still deal with, is this sense that I’m flawed in some way. And this is because I must have done something wrong for my father to have died by suicide. And that’s kind of a way that parental suicide survivors have some agency in it, because it’s too scary to think that this just happened to me by chance. So I must have done something to make it happen, so I must therefore be flawed in some way for my father to have done this. So that’s a lot. And I’ve realized I’ve kind of carried that with me a long time, but I wasn’t aware of that, but now looking back on it, it was very much a part of I just sort of felt flawed, and therefore I had to hide some part of myself and not be available.

And I also felt like I was missing something by not having a father. And especially when you get to college and it’s kind of new experiences, and new people, and new anxieties. I came from a high school situation where everyone kind of knew my story and knew what was going on, to here where everything’s new. And I really carried this imposter syndrome through a lot of situations and assumed I was missing something because I hadn’t had a father. So I played football here, and I assumed that everyone else had been much more into weightlifting and things like that that they’d done with their father, because they had a father, and I sort of wore that as a badge of shame.

Also, just meeting new guys was uncomfortable, because I assumed that all these people had learned stuff from their fathers that I hadn’t learned, like silly stuff. Like people like playing poker, I had never learned how to play poker. I assumed people just were playing poker with their fathers all day long and all night. Now it turns out I still have never played poker, I don’t know how to play poker, that’s not a key life skill. I never had Buffalo wings or anything like that, and I assume people were just eating Buffalo wings with their fathers all the time. I since have had Buffalo wings, that is probably a life skill. I’ve taught my children, my sons, how to eat Buffalo wings.

So that really colored my experience here. And really the result was, I had an extremely thick protective shell of sarcasm that kind of was my operating model to protect myself. And I used humor, which was probably 70% good-natured, 30% not good-natured humor, as a way to make friends and get people to like me, but also simultaneously hold people at bay, because I didn’t want people to know me that well, because then they would learn that I was flawed, because I must have been flawed, otherwise my father wouldn’t have done that.

So there’s been a lot to unpack. That being said, the single most important thing that could have happened to me in college did happen to me, which like a lot of Princetonians, I met my wife. So that was a great outcome. But yeah, I’d love to say that, again, I had access to my father and I was able to experience Princeton as his son, as the son of an alumnus, but it wasn’t available to me at the time.

LD: Now you had mentioned that it was poignant for you when you had your 25th reunion. I see you’re wearing your class jacket. It’s great. So exciting. I see the 1999 buttons on—

SL: Yeah, there’s lots, there’s these things, there’s this, people wore it inside out. There’s a lot going on. As you know, these things are very well considered. So there was a lot of effort by a lot of our classmates putting this together.

LD: So now you have been involved with, you called it the AFSP, that’s the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. How did you get involved and what kind of work have you been doing for them? Volunteer work, I know it’s not your day job. And what kind of reaction have you received for telling your story?

SL: Yeah, so now that we’re in the now now of my story, I kind of had an awareness of the impact that this trauma, first of all, I had an awareness that it was a trauma, that I went through a trauma, and the impact that the trauma, both my father’s death, but then also the middle of my story had had on me, and so was wanting to figure out a way to help people not go through that. And I listened to an interview with someone and they made a claim that they had done more to protect the environment than anyone in the history of the world. And without getting into the details of whether that was accurate, it really just kind of struck a chord with me of like, oh, it’s possible to pick a cause and to have an amazing amount of impact on that. If everyone’s doing it, that’s a lot of people doing it, someone has to be the best. Could you have the most impact on a given cause as anyone?

And so that really sort of is like, OK, I could try to have a major impact on suicide awareness, suicide prevention, bringing comfort to those impacted by suicide. So I did research and realized that the AFSP was the largest organization. And so from my perspective, the way to have impact is to help someone that’s already having a great impact to have a multiplier effect. And then I thought through, OK, I’m probably 47 at the time, I’m not a health-care professional, I’m not a mental health professional, I’m not a social worker, so what resources and skills do I have to have impact? And so really was, I have my story, which I can figure out a way to tell people, and share with them, and destigmatize suicide, and try to be vulnerable and show them that that’s OK. And then my professional experience. The other thing I do is work with the revenue team at the AFSP to try to generate revenue through development, through corporate partnerships and things like that. And so those are the two areas that I’ve been working with them.

And in terms of the essay I wrote, so far, I think the feedback has been twofold. There was a lot of people that are just grateful. You know, thank you for writing this. Some people had a particular person they wanted to share it with that they thought it would’ve been impactful, but just grateful.

The other one that’s been interesting is that people have said, oh, this must’ve been so hard to write, which was interesting to me, because my perspective is, nothing in the now of my story is hard. It was the middle of the story that was hard, when I was kind of tying myself in a knot in order to reconcile what was going on without dealing with it. It’s the example of a lava pit. Now that I’ve processed the lava pit, living in the house is easy. It was when I avoided the whole side of the house that had the lava pit in it that it was hard. So it’s been interesting to me people say, that must’ve been so hard to write, I’m like, no, it wasn’t hard at all. Everything now is very easy compared to what it was like before I processed this.

LD: So what was it like going to your 25th reunion and receiving this class jacket?

SL: Yeah, so again, I talked about how both in the application process and being the student process at Princeton, and really frankly in being an alumnus process — for the last 20 some odd years, my father wasn’t available to me, because I hadn’t really processed what it was. It was sort of still living as this thing that I thought had happened in the past. And it was only being back for our 25th reunion, and by the way, we did our 25th reunion the same as we did our 20th reunion. It wasn’t like we had experienced a different, my wife and I both came, we were fortunate to have our children come for a very finite period of time through the P-rade. But it was because I had really processed what my father’s death was in my life, that his memory was now available to me, and I was able to be aware of the fact that I’m back at Princeton for our 25th reunion, which is something my father didn’t do. He died before his 20th reunion.

And I was aware of, OK, I have ... And I am getting to that stage in a number of parts of my life. I’m now seven years older than he was, and I have children that are older than his oldest child was when he died, and my youngest child is almost as old as I was. I was the youngest child. And so it was really being here and being able to be aware of and have access to the fact that we had both gone here, and I had now lived and accomplished something that he hadn’t in Princeton, that was very impactful for me. And just having access to that, and the jacket was kind of a manifestation of, OK, he literally never got this jacket. I know classmates of his, I know what the jacket looks like, I know that he doesn’t have one, and I know that my wife and I have ours. And so that was really impactful to me, which is why, as I said, I’m never going to not wear this jacket when I have occasion to wear it, which aren’t that many. It’s kind of the most expensive jacket I have in some ways, but also the most valuable. So when I have a chance to wear it, I will wear it.

LD: So Stephen, thank you so much for coming here and taking the time to talk to me today about this. This has been really interesting. I’m hoping that it helps people, just like what you’re finding out there.

I want to put in one more plug. The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention has great resources on its website. And one more time, I just want to say that if you or anyone needs help, you can reach the suicide and crisis hotline by dialing 988 and you can text the crisis text line by texting talk, that’s T-A-L-K, to 741741. Thank you so much, Stephen.

SL: Thank you very much for having me.

PAWcast is a monthly interview podcast produced by the Princeton Alumni Weekly. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and SoundCloud. You can read transcripts of every episode on our website, paw.princeton.edu. Music for this podcast is licensed from Universal Production Music.

Paw in print

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

No responses yet