Vocalist Charmaine Lee ’14 Is Taking Her Mind-Bending Music to All 50 States

‘At what point does life become music, become sound, become music, become life?’

Charmaine Lee ’14’s music might be unlike anything you’ve ever heard before. Lee grew up in a musical family and studied jazz at Princeton along with sociology. She also sang with one of Princeton’s a cappella groups, and the experience inspired her to pursue her own auditory art. Right now, she’s on a tour of 60 shows through all 50 states, and she has a new album out, titled “Tulpa” and released by her own label, Kou Records, which she runs with her partner, Randall Dunn. On the PAWcast she discussed how and why she creates her art — and shared some of it as well.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT:

[Clip of “Overlevered” from the album Tulpa]

This is the Princeton Alumni Weekly’s PAWcast, where we talk with Princetonians about what’s happening on campus and beyond.

Right now, you are hearing a track created by Australian vocalist Charmaine Lee, from Princeton’s Class of 2014. And if you’re like me, it’s like nothing you’ve ever heard before. Lee grew up in a musical family and studied jazz at Princeton along with sociology, and she’s carved out an innovative niche in the world of auditory art. Right now, she’s on a tour of 60 shows through all 50 states, and she has a new album out titled Tulpa and released by her own label, Kou Records, which she runs with her partner, Randall Dunn. Lee agreed to come on the PAWcast and discuss how and why she creates her art, and stay tuned, because we’ll also get to hear more of it.

LD: Charmaine, thank you so much for making the time for this, especially during your tour.

CL: Thank you. It was quite a dramatic approach to landing this, but I’m so happy that we can be together and be able to talk through this really epic project that I’m on.

LD: Let’s start this way. Could I ask you to just explain your work in your own words?

CL: I would say sometimes it’s been helpful for me to describe it as, it’s like you’re watching somebody create an abstract live painting in the moment. The other ways I’ve heard it be described is it’s like exorcism meets beatboxing, which is obviously a very, I kind of relate to it on some elemental level.

I would say the process is improvised, and it’s comes out of a discipline that I learned at the New England Conservatory from my master’s when I went there after Princeton, and I studied with the amazing guitarist Joe Morris, who has developed this kind of meta methodology towards what he coins as free music. And it’s music that primarily is improvised, but it has a framework and a discipline behind it that we can talk a little bit more about. So I would describe it as the process first, which is making real-time decisions in that moment based upon a language that I have developed and a vocabulary.

And then the sort of aesthetics of it, kind of at this point, oscillate between what you could loosely define as noise music, wherein you are primarily using textures and timbres and extremities of sound to create your language, and less kind of functional western harmony or other kind of languages. But at the same time, I think there’s a lot of commonality there, and it doesn’t exclude that. Yeah, that’s where I’m at right now, how I would describe it.

LD: So tell me about your journey to what you’re doing now. How did you get here? Where did the concepts start? And I’d love to know what role Princeton played in all of this. I know you did a lot of music here. Did you do a cappella perhaps, just a guess?

CL: Yes. So I first learned how to create with my voice unaccompanied through the glorious culture of a cappella at Princeton University. I was recruited by Shere Khan. It is a group that started in the ’90s, but I had prior to that zero idea of what a cappella even was. And actually it started when I had opted in for Outdoor Action as a freshman. And somehow, I mean, prior to that I had been singing, I’d loved to sing, and I grew up in a really musical household, and especially jazz and classical music. My dad’s a great, great jazz guitarist, and my mom’s an amazing multi-instrumentalist, pianist.

Somehow, I think night two or three into Outdoor Action, I started to serenade everybody to sleep. It was like a ritual for everyone at night was that I would sing some lullaby or jazz standard or something. And it became this thing where I was singing to these basically complete strangers every night for the whole duration of Outdoor Action, which was totally wild. At the end of it, the upperclassman who was leading us on this program pulled me aside, and she was like, you should really try out for a cappella. And I was like, “What is that?”

So I went to the open houses, and I remember meeting, I was very intimidated by these upperclassmen and the folks, they seemed so cool and interesting. But I auditioned for a couple that I just happened to randomly walk into, and one of them was Shere Khan. I believe that year that they accepted me was the only one that they had accepted out of hundreds of candidates, and The Daily Princetonian wrote an article about it because I guess across the board there were very few admittances of freshmen in a cappella that year. So it was some crazy super competitive process that I was kind of blindly ignorant to in many ways. That changed the course of a lot of things for me and socially, intellectually, emotionally at Princeton. That became my foundation for a lot of reasons.

And creatively, it became this playground for me to use my voice all the time. I mean, we were rehearsing three times a week, three-hour sessions outside of that. We were constantly singing, and I was really passionate about that group. And I became music director pretty early on in my time there. And so a lot of my efforts and energy were put towards this a cappella and arranging, directing. I also was the beatboxing percussionist too, and I think that’s where I developed a lot of my comfortability with percussion and creating sounds that aren’t necessarily conventionally singing per se.

And then that was really a formative time for me in many ways. But I simultaneously was a part of the jazz program too. And in one specific class, they had invited a guest, a percussionist by the name of Adam Cruz to run a session one day. And I will never forget this because it was the first time in which I had an instructor walk into the room and say, “Today’s agenda is no agenda. Today, we’re just going to make music from nothing. There’s no score, there’s no lead sheet. There’s simply just create.”

And I found that experience so both terrifying and so exhilarating, and life-affirming. And it planted this very deep seed in me because it was the first time that I’d been in a situation where I was asked to create, but not to adhere to preconceived rules or aesthetics or language, but rather something from within and that was not going to be judged from an outside alternate framework. And it ignited something really deep in me, and that is a feeling, I mean, I was a sophomore at that time, and I never let it go. It was sort of this thing where I always was pursuing somehow trying to chase that feeling again. And it wasn’t until I was a senior, and I was basically crossroads of deciding what I was going to do after graduating.

The summer before my junior summer, I’d worked at a advertising company, a large advertising company in their strategy, and I had received a job offer for that. And at the same time, I was also still, this little tiny nugget was inside saying, “I think you should explore music just deeper because you haven’t formally really done that in a concentrated environment,” and there’s that feeling. And I kind of had this classic situation where I was like, “Do I want to spend the rest of my days thinking about how to sell Dannon Yogurt forever, or do I want to chase this annoying thing that will persist?”

And I had decided to look into a couple of conservatories, and I had heard a lot of cool things about NEC, New England Conservatory. It was a small program in Boston, and I auditioned, and I ended up getting in, and it was a tiny program. I mean, amongst my vocalists, it was two other people. And I remember the first week of classes they had you sign into, there was a pamphlet you could look into, and you could sign up for various ensembles. And there was an ensemble called the Free Music Ensemble. And in the description it was, “We will play through the music of Ornette Coleman, Anthony Braxton, Steve Lacy, Eric Dolphy,” and all of these names I kind of knew, but I wasn’t really familiar with their music.

And it was led by Joe Morris. I signed up. And in that ensemble, I learned the music of the folks I mentioned, but also Joe’s method. It was the key. It was the context and the framework and the history and the environment that just unlocked this, now what is a 12-year journey.

When you are improvising with another person, you’re basically adopting one of five different states. You’re either soloing, juxtaposing, complementing, in unison, or you’re silent. And those modes, as you can imagine, they’re very conversational in their nature. And it creates this very high degree of intentionality every time that you are creating something with someone. The frameworks are broad enough that you can connect with someone who comes from a conservatory training or someone who plays whatever God tells them to play. There is this broad enough approach where you can really relate to people who come from lots of different backgrounds and practices. At the same time, it’s very focused, and it allows you to create a constant sense of relationality to the music and regardless of preconceived skills or motivation.

So it completely opened my mind. I began to pursue lessons with him, Joe, independently, and together we created this. At the time I was listening to a lot of music and seemingly disparate music. And through Joe, I was able to synthesize a lot of those practices into this very personal language that I use today.

LD: Now I want to ask you more about how you do this, but before we do that, let’s listen to just a little bit more of what you do to give people an even better idea of what we’re talking about.

[Clip of “The Loading Zone” from the album Tulpa]

LD: So tell me, so what are the mechanics of how you create these sounds? I know you have, I’ve seen videos, you have a microphone in front of you, maybe one on your throat, and are you using your vocal cords in some way that I didn’t know was possible? How are you doing this?

CL: A whole bunch of smoke and mirrors and trickery. I am using four or five microphones at the same time. So my obsession conceptually is, in general, and in life, is how do I achieve the illusion of a thing without necessarily doing the thing in and of itself? And sometimes, most times for me, that thing ends up being more interesting than the literal doing of that initial idea. So with the microphones, basically I have them placed, I have a standard dynamic microphone that I have, and then I have a contact microphone on my throat. And then I use a collection of lower fidelity microphones, like a cassette tape player that I got from GE on eBay that has a tiny little component in it that’s super crunched. And what I do is I suck on that, and I actually live, I take the little headphone jack, and I put it into my mixer, and then I’m live monitoring basically that microphone.

And then I have a couple of others including a small skinny microphone that I got from another RadioShack tape player. And then I actually also have another RadioShack — RadioShack should have sponsored me at this point — but I also use a RadioShack radio so that I can really kind take AM-FM signals from exactly where I am in that moment. And it’s this really great surprise constantly, especially I’ve traveled the world with that radio, and so you never know what is on the stations in that moment. And so when you put it in the music, it’s really fun.

But basically my goal with using all of these different microphones is to create a sense of polyphony from basically what is a single sound source. There’s so much information actually that can come from just basic placement on our bodies, on our throat, using microphones that are actually so rich and complex with information and texture and orchestration. And I’m really interested in creating, not only trying to push the boundaries of the complexity of what that could be, but also creating this almost internal-external dialogue with my body. By having the contact microphone on my throat, I’m accentuating sounds inside that you really wouldn’t be able to hear any other way. Even the sound of swallowing, you’d be so surprised how much is there actually.

And I do other fun kind of things like that in my language. I gargle water. I do what they call an ingressive vocal fry, where when people talk like this, and that’s considered what they would call vocal fry technically, but the ingressive version is if you’re doing it breathing in. So this sort of breathing in actually creates an incredible level of rich overtone texture. It has its own little internal rhythm because of how your construction of your throat is. And when you put a contact microphone on that area, it’s incredible. I mean, you have an entire 60-piece orchestra that lives there. So I’m really fascinated with how far can that go in what is deceptively a simple kind of approach.

And recently, I mean, in the past five years, when I first started, I would just have those microphones running through a mixer, and then I would use the mixer’s EQ, equalization bands, to adjust certain lows being up or treble notes being up, and how that would inspire me to create language around that. And was basically using that for quite a while and building in language around that setup. And then in the past six years or so, I’ve started to really think about how I can use other technologies to further accentuate and augment and distort that language.

So during COVID, I started getting interested in modular synthesis, and in Eurorack specifically. I have built this system that essentially allows me to then do more with what I have existing. So whether that’s stereo, panning, there’s some spatialization there, or reverb, like massive amounts of reverb to a really, really dry signal, taking some elements of the language, and then cutting it up and sampling that and resampling that. So that’s kind of where I’m at right now with how I’m relating to additional electronics. But the core of the language still very much lives inside the body, and I’m always interested in that and the ways that we can get to the effect of something without necessarily running it through a bunch of keyboards and electronics, etc.

LD: Now I’m thinking about your listeners because you’ve got the album, so people will listen to the song their own, but they also come to these performances. What are you trying to convey or say to people who are listening to your work? Obviously, I mean, it’s not a typical concert. They’re not going to be dancing or singing your songs—

CL: Oh, you’d be surprised.

LD: Really?

CL: You’d be surprised. I performed at a rave in rural New Jersey about two months ago in Sparta, and it was totally awesome. It’s called Dripping Festival. And it was so fun because I started the set, someone stood up, and then by the end of the entire show, the entire festival was writhing around. It was the most incredible experience being able to have just hundreds and hundreds of bodies just moving, moving, moving, moving while I was playing. And so then I really dug into it, and I think the set was super rhythmic and funky. It’s awesome. You’d be surprised how many people are compelled to move when they hear music like this.

LD: Amazing. That is so awesome. All right, so I stand corrected.

CL: No, but I will say, no. I mean, the intention is as a vocalist, it’s very tempting to make things literal. I mean, when you’re using such a universal instrument, it’s very hard not to separate association with abstraction. And when I was first starting, I was kind of treating performances almost like a theatrical monologue and sort of guiding the listener through certain emotional pathways that I was feeling connected to at that time, somewhat subconsciously. I kind of got bored of that pretty quickly because I think I am more interested in allowing for a listener to interpret it their own way, because I know for a fact that by using the voice, there will already be hundreds of associations with every sound I make. And allowing for a listener to then create those associations for themselves, I have found to be a more powerful way to connect with people.

That isn’t to say I’m not thinking about narrative and storytelling in doing this. When you’re creating music, it is a linear experience, but it is also not. It’s this incredible, probably the only art form I know that exists that is so abstract in how we experience it, because at one end we remember what happened 30 seconds before, and on the other end, we are completely, the only way we can know what is happening in this moment is because of the context it came before.

And I find that so incredible and fascinating. It’s a real purpose, I think of mine in doing this is to create these almost cinematic narratives that happen when I play, but it comes from a very subconscious place. It comes from the place that prioritizes what exactly is needed in that moment. It doesn’t come from a preconceived intention, outside of the intention of presence and of risk taking. And so when I mean that when I’m performing, I like to try to bring myself almost to the edge of nowhere, is how I would describe it, in which at any one point if I were to lapse in focus or concentration and intention, the whole thing I just built could collapse. And that feeling, that is very thrilling to me. That’s what I refer to when I refer to risk taking is that sensation of bringing yourself just to that point where you almost don’t know what’s happening. And it’s built upon though, like a practice, a language, a toolbox that I kind of refer to.

When I’m practicing, I’m basically going through hundreds of different combinations of this language. So whether it’s the dynamic mic to the contact mic, doing something in the contact mic, synthesize with the cassette tape player, and how do I shift through these things? What kind of language can I build through the combination of these microphones together, etc., such that when I sit down and actually perform, that comes out ad hoc and I’m able to pull out from this toolbox, depending on what I feel is needed in that moment. And what drives those decisions is basically some combination of the physical space and the sound system and the acoustic properties of that space in combination with the audience and their energy, what I sense from their level of openness and whether or not they can kind of go on a more nuanced journey with me or something that’s more kind of brute and dramatic in that way.

I can kind of intuit what the sort of vibe is, and then I kind of create a relationship to that that both invites people to participate and be present with me. And at the same time, it doesn’t beat them over the head with that. At the end of the day, I’m not really interested in coercing people to listen. But at the same time, I’m not going to necessarily compromise beyond a certain point that compromises the intention.

For me, a successful performance is not necessarily one where I nailed it. It’s not really about the execution of a preconceived idea. It’s actually about presence and commitment. So did I make those decisions, and did I back myself a hundred percent behind those decisions that I made in that moment? And did I commit to presence? And those things are kind of a slightly different parameter, I think, than when we think about a successful classical music performance or something like that. But I find that that is incredibly life affirming and increasingly becoming a more rare opportunity, both as an audience member and as a performer to be present, to truly be present. And so that’s really the intentions, I think, for me at this point.

LD: Well, and we all struggle to be present, fully present these days. That’s well documented. What is the reaction like from the people who hear you? What do they say? It strikes me that as different as each of your audiences are and each of your performances are, because of all this improvisation, probably everyone reacts a little differently as well and kind of brings their own experience to it. What has the reaction been like?

CL: I’ve had the full gamut. I’ve had people throw things at me, scream like, “Why are you doing this?” And in some way it’s like, I think because we’ve been so conditioned, especially when we hear music now, we’ve been so conditioned to hearing it passively. Usually now it serves an alternate activity like studying or cooking or cleaning, and there’s music that lives for that purpose. But music that simply lives as music to be listened to, deeply, it’s becoming more of a rarity in our daily life. It’s becoming increasingly harder too. I’m a millennial, but the generations under me, it’s really hard to focus more than 15 seconds, quite literally. It’s challenging to do that. And I think that it’s affected all of us, I mean, not just the younger generations.

I’ve had the gamut of really adverse reactions, not only because of that, but because the voice is so direct as an instrument that you’re like, “Ah, this isn’t the thing that you should be doing with your voice.” But ironically, if they were to kind of dig a little bit below the surface, there’s an entire, cultures and practices and histories of people that have been using their voice like this for a long time.

But more often than not, most people who hear my music, especially live for the first time are like, “You were doing the thing, the sounds that I hear inside my brain all the time.” I’ve heard that many, many times that there’s some sort of connective thing that happens internally. It’s sort of just speaking to what I was saying about the internal-external dialogue. I’ve had a lot of people say, “That is literally the sound of my brain. That is literally my most elemental sound that I hear,” which I find really fascinating.

What I really love is when I perform for kids, I’ve done a bunch of more educational settings where I once did a workshop for 9-year-olds, and it’s so fun and fascinating the ways that young kids relate to this music because they’re not really hearing it necessarily as music. They’re hearing it as the sounds of their life. I’ll have the kids be like, “That’s the sound my dad makes in the bathroom in the morning,” which is so awesome. It’s the best thing about it, where it’s like, at what point does life become music, become sound, become music, become life? And I love to ride that line a lot in being able to use my voice.

But fundamentally, for me, it is music. And I’m very much using, ironically, pretty traditional methods of, or characteristics, that make music music. I mean, harmony, rhythm, tonality, melody, all of these things are what we characterize as music. So I am very much still driven by those principles, but the aesthetics of that and my approach to how I get there is maybe a little more unusual than others.

LD: This has been so interesting. Is there anything else that you wanted to touch on or anything you’d like people to know?

CL: Yeah, I would love to talk a little bit about the tour, and there’s some philosophy around it that is really important to me, which internally this tour is, it’s a hundred days, it’s 60 shows. It’s over 20,000 miles of the road. And what motivates this is both something really personal, which comes out of actually an incredible piece of history in my family, which I think could be interesting to mention.

My father’s mother, her side of the family, her grandfather migrated to Mendocino, California, in the 1800s. Like many, he was working on the railroads, and he eventually ended up running the general store in Mendocino. He actually went on in that time period to found what now is the oldest Daoist temple in America, which is crazy. And it’s called the Temple of Kwan Tai, which is named after the sort of god of war. It’s still there.

His son, who was born in Mendocino, when he was 14, he left to China to his ancestral village to learn about the language and learn about his culture. And when he tried to return, he was not let in. He was banned from entering. They had just mandated the Chinese Exclusionary Act of 1882. And so he consequently sued the San Francisco courts, and he won. And that became one of the landmark cases that they cited in the Wong Kim Ark case that created the whole precedence for birthright citizenship.

So it’s a totally nuts, crazy story, and it’s something that I have only really learned in the past three years about my life, and has opened my relationship to an understanding of Daoism, which has kind of waxed and waned over the course of the generation since then. This tour is a kind of Daoist love letter to myself to sort of understand the experience of letting go, of being present and for allowing for things to happen as they will. Not to try to control things so much, which I kind of learned very intensely in my corporate day job life.

And to be present and to learn how to be one with what’s happening in this world. Externally, I think the way that we’re mapping this tour and with my partner Randall, who is an incredible producer and engineer and has been touring for a long time and is very experienced with this. But our goal, I think, is really not to just go to major cities in this country, but to small towns. I played in Laramie, Wyoming, and I had two comedians opening for me. We played at, what is the highlight of this tour for me so far, we played at a Lakota skate park in Pine Ridge, and we hung out with the native community and spent a couple of days with them, which was totally life changing.

It really is about bringing this music to far off places and reminding people of what music can do outside of the news cycle and the information cycle that we’re in. So it’s a really important life project that I’ve embarked on, and we’re a month in, and I’m learning so much about myself and about the world and about this country as a result of that.

LD: Thank you so much for taking the time for this. This has been really cool. And good luck with the rest of your tour.

CL: Thank you. I will hopefully make it out alive.

LD: Next tour, next tour, you’re going to stop at Princeton? Yeah?

CL: I will come to Princeton at a different time. I’m already in touch with a couple of awesome people that run the live music opportunities there and have known a couple of them for a long time. So actually I know I will be there around March. Jeff Snyder, who’s an awesome electronics professor, the head of electronics music, I think there at Princeton, is organizing a mini festival for voice and electronics, so I’ll definitely be there.

LD: Oh, amazing. All right, well, we’re going to look forward to that.

CL: Thank you so much, Liz.

LD: Yeah, thank you.

[Clip of “Moebius” from the album Tulpa]

PAWcast is an interview podcast produced by the Princeton Alumni Weekly. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Soundcloud. You can listen and read transcripts of every episode at paw.princeton.edu. The music in this podcast is used with permission from Charmaine Lee, with tracks from her album Tulpa, titled, in order, Overlevered, The Loading Zone, and Moebius.

Paw in print

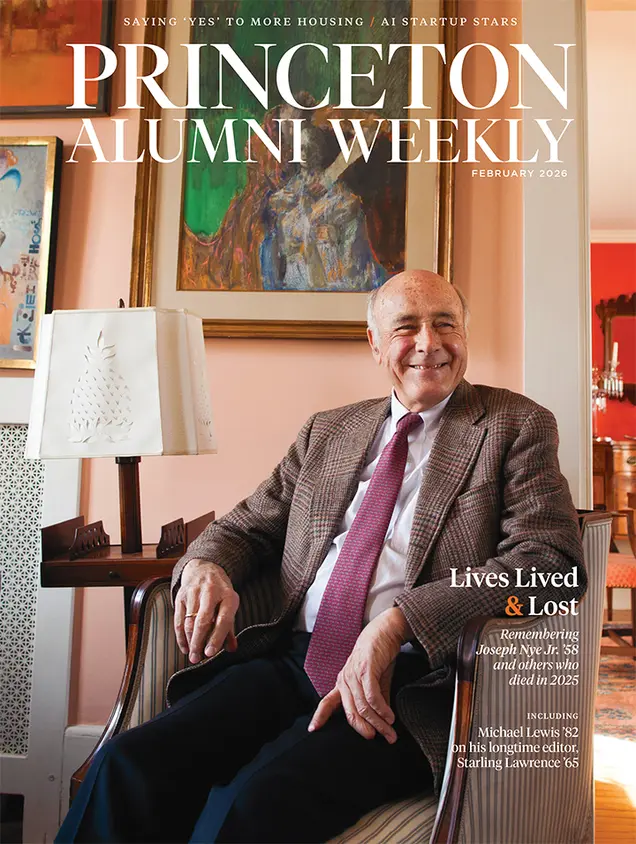

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

No responses yet