Their season of glory began in tragedy and defeat.

The undefeated 1964 football season might be said to have begun on Nov. 30, 1963, in a heartbreaking 22-21 loss to Dartmouth. That game, postponed a week because of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination, drew a crowd of 35,000 to Palmer Stadium. Princeton clung to a narrow lead until an uncharacteristic fumble by fullback Cosmo Iacavazzi ’65 *68 on his 2-yard line set up the winning Dartmouth touchdown. The Tigers were forced to share the 1963 crown.

But the rising seniors on the team would not taste defeat again.

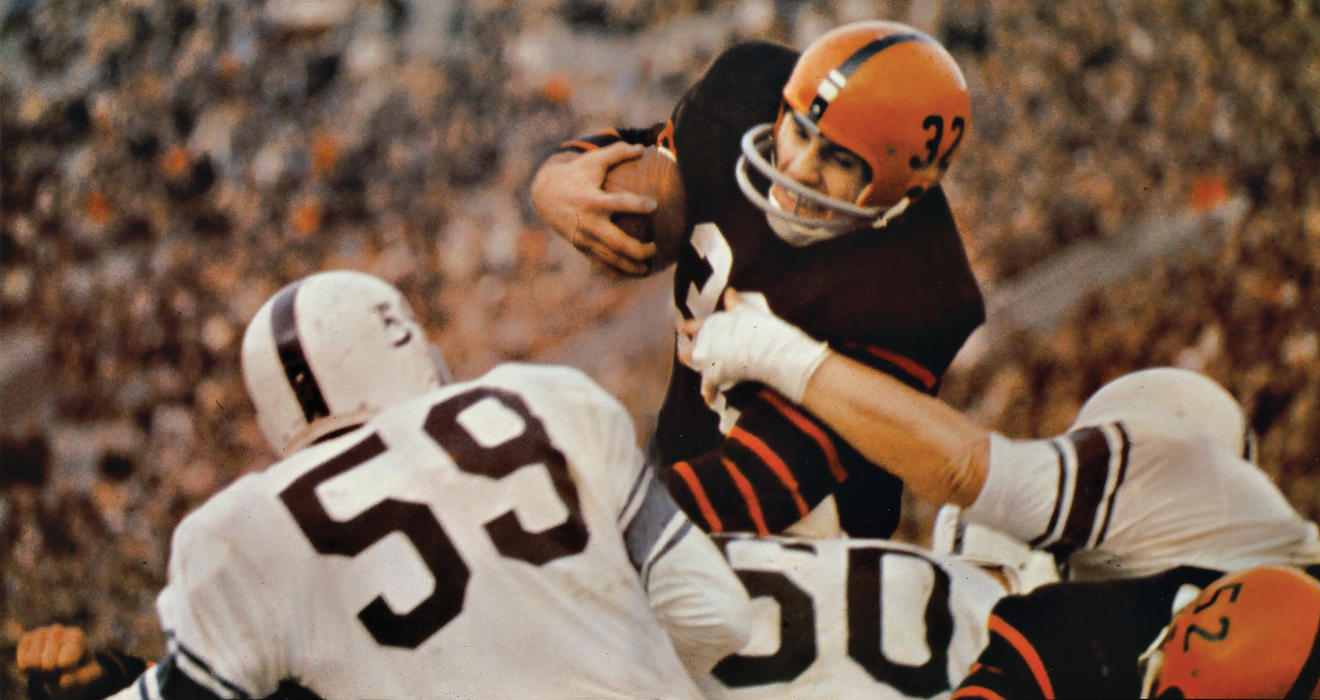

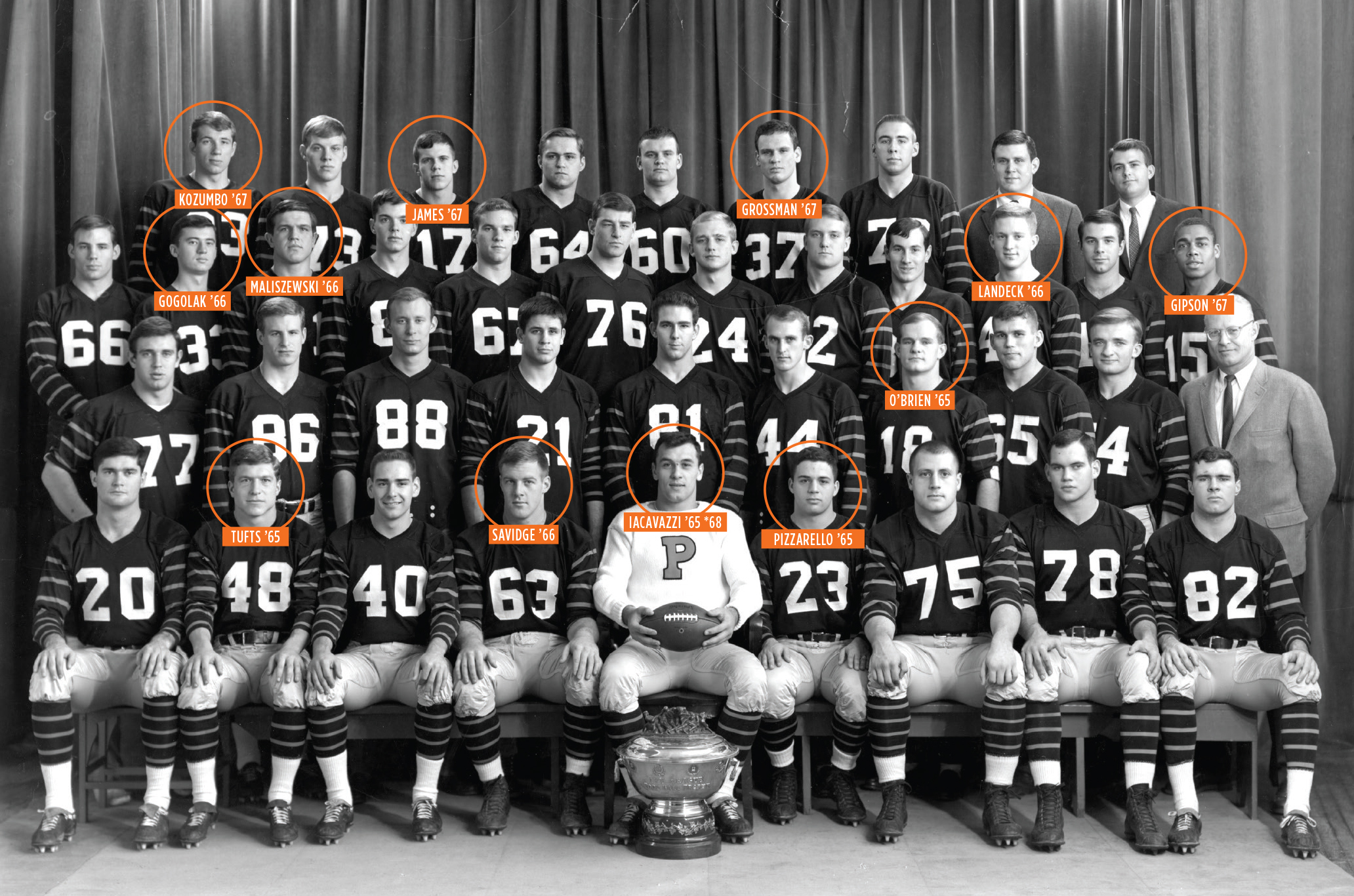

In 1964, the Tigers mowed through their schedule, finishing with a record of 9-0 and outscoring their opponents 216-53. Team honors followed — in addition to the Ivy title, Princeton was runner-up for the Lambert Trophy as best in the East and finished ranked 13th in the UPI coaches’ poll — as well as individual honors. Seven players made first team All-Ivy and Iacavazzi (called “The Roar of the Tiger” by Sports Illustrated) and Stas Maliszewski ’66 were All-Americans.

“Somebody up there must have been looking out for Old Nassau this year,” A. Franklin Burgess Jr. ’65 wrote in PAW.

MEMORIALS PAWCAST: Remembering Ernie T. Pascarella ’65

However, the season also marked the end of an era, or at least the beginning of the end. Vietnam and protests were about to rock the campus and the country. By the end of the decade, Princeton had moved on from its distinctive single-wing offense and would never again achieve the same kind of national prominence on the gridiron.

Now in their 80s, the surviving members of that 1964 team remain close and, when they can, return to watch the current team play. Six decades later, they like to look back on their perfect season, retell some old stories, and share a little of what they have learned about the game and each other.

As the 1964 season began, some used the Dartmouth defeat as a spur, but others tried to put it behind them.

Iacavazzi: I felt I’d let us down. From a personal point of view, I just made it a point that I would never drop the ball again. Never.

Ron Grossman ’67 (linebacker): When we went to training camp at Blairstown, Cosmo handed us all Avis buttons. Avis was the number two rental car company, and they had a slogan: “We try harder.” That was our motivation.

Doug Tufts ’65 (wingback): I wasn’t even thinking about it. I was just thinking: Bring it on. Bring on the new season.

By modern standards, the team’s training regimen was spartan.

Maliszewski (linebacker/guard): There was no weight room.

Tufts: Being a little guy, I did a lot of my own weight training. I had a setup in my backyard with dumbbells and barbells, because a big part of my responsibility was blocking. I had a routine where I would use them to simulate getting underneath a 300-pound tackle and doing what I could.

Paul Savidge ’66 (guard/defensive tackle): During the summers, I would put on my winter coat and these great big insulated boots. The owner of the farm I grew up on had these riding paths through the woods. So, I’d be running with all this weight on thinking, if I survive this, Blairstown will be nothing. I’m lucky I didn’t die of heatstroke.

By 1964, Princeton and Penn were among a handful of programs in the country still running the single-wing offense, which emphasized precision blocking, speed, and elusiveness.

Iacavazzi: The ball would be usually snapped straight to me at fullback or straight to the tailback. The single-wing backfield setup was sort of like today’s shotgun formation, if you will. I’d be standing alongside or behind the tailback. And most times we would get the ball directly and run directly.

Dick Colman was entering his eighth season as head coach after succeeding the legendary Charlie Caldwell 1925 in 1957. An All-American at Williams, where he lettered in six sports and later coached lacrosse, Colman would be inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1990.

Roy Pizzarello ’65 (quarterback): He was a Quaker, which always surprised me — a person sworn to nonviolence who spent his career coaching football! But he was a good strategist. He never cursed. The worst thing he ever said when he got angry was, “Ten thousand fiddle-dee-dees.” Or if you dropped the ball, he might say you should have died as a baby rather than fumble.

Tufts: He had high expectations for us. And when he gave us instructions, I just thought he had faith in us that we could meet his high bar.

Dick Springs ’64 (wingback): In 1963, maybe ’62, we started using this huge mainframe computer to analyze our film. We’d have quarterback meetings with Colman on Friday afternoons and he and the coaches would pull out these computer sheets and tell us, you know, on third and 6, they’ll be in this defense. And these are the plays that might work against that. We knew more about what the other team was doing than they knew about themselves, because we were the only people using a computer at that time. [Springs had graduated before the 1964 season started. He died two months after this interview was conducted.]

Princeton’s leading scorer was Charlie Gogolak ’66, a Hungarian refugee who, with his older brother Pete who attended Cornell, became one of the nation’s first soccer-style kickers. Opposing teams sometimes tried to block Gogolak’s kicks by stacking defensive players on each other’s shoulders. The NCAA outlawed the tactic in 1966.

Gogolak: I have to admit that sometimes they did distract me. And sometimes they didn’t. If I made the kick, they didn’t. I’m sure you’ve seen the photo where there were two defensive linemen standing on the shoulders of two tackles. It hit all the magazines. I remember going up to [assistant coach] Jake McCandless [’51] and saying, “Jake, what do I do?” He said, “Kick just the way you normally do. Don’t worry about hurting anyone. If you hit one of them in the head, that’s his problem, not yours.”

After a narrow victory against Rutgers in the season opener and a win over Columbia, Princeton traveled to Dartmouth. It was the first game Princeton had ever played in Hanover and the first time the team had ever flown to a game. For the juniors and seniors, it was a chance at redemption.

Maliszewski: Any time you lose to somebody, it’s a frickin’ revenge game, OK? I mean, when I think about the seasons I played [1963-65], we only lost three games. The only games that have made a lasting impression on me are those three games. We shouldn’t have lost any of them.

Iacavazzi: I scored one touchdown on a pass across the middle, and the Dartmouth linebackers didn’t know what to do. They were expecting me in the backfield. You can see it in the film. All three linebackers keyed on me. But I wasn’t in the backfield. They literally didn’t know what to do.

Now firing on all cylinders, the Tigers won their next four games — against Colgate, Penn, Brown, and Harvard — by shutouts.

Pizzarello: The Harvard linemen were some of the toughest ones to block. They were very big and very strong. I wasn’t very big. My senior year, believe it or not, I weighed about 160 pounds, and I was blocking guys who were 230, 240. Against Harvard, I remember telling [Iacavazzi], “I can’t block them out, I’ll block them in.” So, whenever we went around end, I’d block them inside and he would run outside. And it worked out pretty well.

Princeton clinched the Ivy League title with a 35-14 victory at Yale, but the game was closer than it appeared.

Savidge: I’ll never forget that walk into the Yale Bowl. The Yale alumni were lined up against the fence as we came through, and they were yelling at us, stuff like, “You freaking this-and-that!” And I said to myself, “My God, these guys are all doctors and lawyers and successful people! What the hell?” If the Yale coach had known what his fans were doing, he would have shot them, because if we weren’t ready when we got there, we were ready after we went through that gauntlet.

Iacavazzi: I thought that was our toughest game. They scored on us first, the first time it happened in the whole season, and we were tied at halftime — the first time that had happened, too. We were tight. You know, it’s a big game. When we got to the locker room, Colman just looked at us and said, “Worse things have happened. Lincoln was assassinated.”

Grossman: I remember him saying Lincoln got shot and thinking to myself, what the hell does that have to do with the game?

Iacavazzi: It was almost laughable. You’re in this macho setting at halftime, and your head coach says something like that. But it loosened us up. We really broke it open in the second half.

Pizzarello: Yale is a very intelligent school, but when they wanted to blitz right, they’d yell, “Roger!” And when they wanted to go left, they’d yell, “Larry!” After about five minutes of that, we figured it out.

Heading into their finale at home against Cornell, the Tigers were playing for their first perfect season since 1951, but the pressure did not affect them. They won the game 17-12.

Maliszewski: Princeton was a different place back then. It wasn’t as big. You’d walk around campus and guys who had nothing to do with football would engage you. Invariably, people would ask, “Are we going to win?” After a short time, I had a standard reply: “You don’t practice to lose. We practiced this week. We expect to win.”

Little commented on at the time, the 1964 season was also significant because Hayward Gipson ’67 became the first Black letter winner in Princeton football history.

Iacavazzi: A few years ago, they honored him with a mural outside the football office in Jadwin Gym. That’s when they said he was the first Black [letter winner]. I didn’t even know that. A lot of us went to the dedication, but I thought Stas had the best line. He looked over at Gip and said, “You’re Black? I always thought you were Polish.”

Ron Landeck ’66 (tailback): Gipson was a great teammate. He was always there for those around him. I mean, always a good sense of humor, upbeat, hardworking.

Gipson (cornerback): I was a javelin thrower in high school, and an older assistant track coach took an interest in me. I had a free weekend with nothing to do, so I decided to go down to Princeton. I was so blown away by how down to earth and open everything was. Princeton became the place where I wanted to go.

The African American population at Princeton at the time was miniscule; I think there were 10 African American students in the entire undergraduate population of about 3,200, though when I was there, it started to grow. But I had grown up in that kind of environment and had always been encouraged by my parents to do what you want to do. Just do your best and keep your nose to the grindstone and go for it.

Princeton would not enjoy another undefeated football season until 2018, by which time the program had moved down from the NCAA’s top tier. Palmer Stadium was razed after the 1996 season, and Princeton Stadium, with a much smaller seating capacity, built on its footprint. Princeton football no longer receives national press attention and occupies a smaller place in the campus athletic consciousness than it did 60 years ago.

Iacavazzi: It’s just as important to the players and coaches as it was to us former players. Personally, I am a little disappointed in the lack of student interest in the games in terms of attendance, but that’s kind of where it’s at today. There are so many competing alternatives.

Gipson: I guess I’m a little disappointed in watching games on TV or when I do get down there. The players just don’t seem as tough. I don’t care what the score is, if I know that they’re really in it to win it, that they’ve worked hard on fundamentals, and they’re playing the game right. And I don’t always feel that. There was a commitment to excellence and fundamentals that I just don’t see as consistently in today’s teams.

Doug James ’67 (safety): Other than the smaller crowds, very little has changed in terms of the devotion of the players themselves. The University has long stood for excellence across the board — academically, athletically, artistically, and otherwise. And I think the quality of play today is absolutely superior.

Gogolak: It doesn’t bother me terribly, except there used to be a certain atmosphere to a game. Palmer Stadium held something like 44,000 people, and you went in there and heard that noise, and it kind of got you fired up.

Landeck: Our game against Dartmouth the following

year, in 1965, was the last time Palmer Stadium was full. Tickets were selling at the Princeton Club in New York for $250 apiece, and there was scalping going on! But I applaud the student-athletes of today who come to Princeton. They make the same choice we did back then, which is that I’m going to a place to get a good education. And football can be a part of that.

Maliszewski: I never considered myself a student-athlete. I was a student — period — who happened to play football. We didn’t have student-musicians or student-actors. We were all just students.

Besides the stories they still love to tell, the surviving members of the 1964 team learned some lessons they would like to share with the current team.

John O’Brien ’65 (tailback): I would just say, think and act like one team every minute. And think like champions.

Tufts: Show up, risk it all, go out and see what you can do. When you see a bunch of guys around you giving their best, you develop a faith that they are going to do what they need to do for the team. And so, you’ve got to do what you can do for the team.

Gogolak: They had a thick paper sign in the locker room. There was a big capital “DE” and then a picture of a tiger tail. De-tail — you see? So, the idea was, Tigers, know your detail. That’s what you saw sitting by your locker, that sign. Everybody knew that if they performed their details, good things were going to happen.

Walt Kozumbo ’67 (defensive end): Our team was not a power team; our team was a guts and gore team. We stuck together. And we really benefited from those older guys. They were our role models. They passed on to us the idea of winning, that you had to really want it.

Landeck: I think about teamwork and really, just the brotherhood. You wanted to get out on the field and give it your all. That’s what I wish for today’s teams, to feel that brotherhood just as strongly, and learning those life lessons out there on the football field.

For fans, at least, one question lingers. How would the undefeated 1964 squad fare against today’s Princeton football teams?

Iacavazzi: They’re much bigger, much faster than we were. Our biggest guy was Ernie Pascarella [’65]. I think he weighed 235 pounds. Now you have quarterbacks who weigh more than that. But our mindset was, we will beat anybody, anywhere, anytime.

Maliszewski: It’s a different world. I mean, you almost can’t relate to it. The weights, et cetera. Just a different ballgame.

Grossman: I think we could give them a good game if we weren’t as old as we are. I think they would be surprised at the quality of football that was played back then. They certainly are bigger and stronger than we were. But I think we could hold our own.

Pizzarello: We’d kick their ass.

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.

8 Responses

Ernest Dreher ’63 *65

1 Year AgoRemembering That Wonderful Season

Regarding your November article on the 1964 football season, of which I have fond memories: I attended all the home games and went to New Haven, where I marched behind our band into the Yale Bowl while they played “crash through the line of blue,” which we did to the tune of 35-14. I went to the celebration after the season and took a six-inch-long white rubber football that I had the following sign: Bob Bedell ’66, Wendall Cady ’65, Charlie Gogolak ’66, Fred Gouldin ’65 *70, Jim Hackett ’65, Cosmo Iacavazzi ’65 *68, Dick Jones ’65, Bert Kerstetter ’66, Ron Landeck ’66, Don McKay ’65, Chuck Merlini ’66, John O’Brien ’65, Ernie Pascarella ’65, Roy Pizzarello ’65, Pete Riley ’65, Ned Porter ’65, Dick Reinis ’66, Don Roth ’65, Paul Savage ’66, Lynn Sutcliffe ’65, Doug Tufts ’65, and Ron (whose last name I cannot read). I would send a picture of the football, but it is totally deflated and out of shape, much like most of us who graduated 60 years ago!

I took 24 slides that fall. Three at Palmer Stadium at an unknown game, one of our band marching along Cannon Green, two of Cosmo scoring a touchdown at Yale, three of the wood being piled up for the bonfire, and 14 of the bonfire as it grew in intensity. A study of orange flames against the black sky!

For those who have recently stated that the bonfire should be eliminated I say Rah Rah Rah, Tiger Tiger Tiger, Sis Sis Sis, Boom Boom Bah Humbug!

Editor’s note: While PAW contributor Henry Von Kohorn ’66 did suggest modifying the Big Three bonfire tradition, the idea of eliminating it entirely was not a commonly expressed view among readers.

Don Joye ’67

1 Year AgoReminiscing About Princeton Football

What a wonderful article you ran in November, “The Boys of Fall in Winter” by Mark F. Bernstein ’83, about the undefeated football team of 1964. I was on the JV team that season, and I have a few memories that were beautifully stimulated by this article, particularly of Cosmo Iacavazzi ’65. Once a week the team had contact practice. In order not to risk damaging the backfield runners, the defense had portable air bags that we’d use for contact. Well, there I was playing linebacker one day, and Cosmo came charging up the middle. So I used my air bag when he came at me, but oh! What a shot! It was a total surprise. He lowered his shoulder, and it felt like a truck just ran me over! Bounced me back a step or two to prevent me from falling on my butt. Yikes! If this is what it felt like for others trying to tackle Cosmo in a game, well, I felt sorry for them!

That team had several others who were almost as tough as Cosmo. Hayward Gipson, of my class (’67), made the varsity sophomore year. I remember more than once trying to block him and feeling like I just hit a brick wall. Then he would throw me aside and chase the play. We had a good fullback in the class also, Dave Martin ’67. His nickname was “Truck”— big, fast, and hard-hitting, if not quite the All-American that Cosmo certainly was.

The team also had some, let’s say “mouthy” guys on it — not a lot, but enough to keep things lively. They kept the spirit up. Ron Grossman was another one for this team. He was a linebacker in my class, and during practice he never seemed to quit. When someone beat him, or it was clear he was tired, he’d take a few breaths, walk away, and come back at you hard as usual.

The ’64 team is the only one that defeated Dartmouth in the four years I was there. Not only did they beat them, but they beat them in Hanover! The ’65 season was another great season for Princeton football. Ron Landeck was our super back that year, and the team was 8-0 before the Dartmouth game in Palmer Stadium. Unfortunately for us, Landeck had been injured during the week. He played, but Dartmouth ended Princeton’s 17-game winning streak, longest in the nation at that time. In my four years at Princeton, we lost a total of five games in football, one to Harvard, one to Colgate, and three to Dartmouth. Grrr!

Thanks for stimulating the reminiscences. It really took me back. I had to drop football after my sophomore year — one of the hardest decisions I ever had to make. I wanted so much to wear those Tiger stripes! Engineering studies were getting harder, and it was clear that I wasn’t going to make it in football, so I managed to do wrestling, where Princeton wasn’t so dominant.

Charlie Henkin ’64

1 Year AgoPrinceton Band at the ’63 Dartmouth Game

The recent PAW had a fine article on the undefeated 1964 Tiger football team, including the unfortunate loss to Dartmouth in the 1963 game at Palmer Stadium.

This game was famously delayed a week following JFK’s assassination. I was in the office of my thesis adviser, Professor Marvin Goldberger (later president of Caltech), when one of his colleagues burst in to tell Goldberger of the (presumptively fatal) shooting in Dallas. As Princeton Band president, I had already approved our halftime selections, including the show song highlighting Dallas “Big D, little A, Double L, AS” as the Band formed a Big D on the field. There was ample time to rehearse a different halftime show. Clearly that selection and our usual irreverent commentary would be scrapped. So we formed in concert formation and played a couple of classic Princeton songs, ending with “Old Nassau.” The crowd joined in singing this ode to Princeton.

Having been previously summoned to Dean Lippincott’s office twice that season following some alumni criticism of our exuberant halftime shows, I was pleased with our performance and alumni praise for the respectful manner in which the Band serenaded the crowd that day.

Tom Newsome ’63 k’36

1 Year AgoFootball’s Proud Class of ’36

Add to the list of Princeton football greats the Class of 1936. Arriving in Blairstown in the fall of 1932, its players reported to the legendary Coach Fritz Crisler. In their four seasons together (freshman and three varsity), they would sustain only one loss, to their arch-rival Yale, finish high in the national rankings, and receive an invitation to the Rose Bowl, subsequently declined by the administration. By graduation, they were duly considered the Pride of Nassau.

Tim Howard ’72

1 Year AgoChampionship Memories

This was a fantastic article about players who I still remember well. My brother, Bill ‘64, was an end on the 1963 football team. Until the day he died he still complained about the loss to Dartmouth in ’63 that prevented the team from claiming sole possession of the Ivy championship. Fortunately, he was captain of the undefeated Ivy basketball championship team in ’64. His daughter, my goddaughter, still wears his white letter sweater to football games whenever I can attend. Thanks for the memories.

Hugh MacMillan ’94

1 Year AgoMessage From a Teammate

Dear Cosmo,

My dad, Hugh MacMillan ’64, the senior wingback/punter in that fateful Dartmouth loss, sends his unmitigated love!

Richard S. Crampton ’53

1 Year AgoOther Legendary Football Teams

Why no mention of Princeton’s unbeaten seasons of 1950 and 1951 with Richard Kazmaier ’52 on cover of Time magazine?

Richard G. Reinis ’66

1 Year AgoThat Extraordinary Defense

Thanks for spotlighting our teams and that remarkable record. I’m proud to have stood side-by-side with those highlighted, and many others who contributed to the success of those teams. The story would be incomplete without mention of the extraordinary defensive record that resulted in our outscoring opponents 216 to 53. The teams on which I played had a killer instinct. Although I was an offensive lineman, I think we all shared the thought that giving up six points a game was too much.