For 80 Years Princeton Has Been Publishing Thomas Jefferson’s Writing

The Jefferson Papers project will contain approximately 20,000 letters written by Jefferson and another 30,000 received by him

The Papers of Thomas Jefferson project, which has been housed for decades in the depths of C floor at Firestone Library, is evidence of that. The project, which seeks to publish all of Jefferson’s papers as well as a substantial amount of his incoming correspondence, marks its 80th anniversary this year. Though it began during World War II, the finish line is still only dimly in sight.

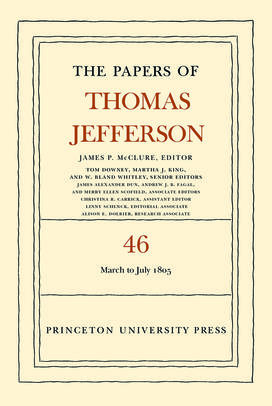

Volume 46 of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson has just been published by the Princeton University Press. Beginning less than a week after Jefferson’s second inauguration as president, it covers the period from March 9 to July 5, 1805, a relatively quiet time, as Jefferson goes. News of important events, such as the continuing Lewis and Clark expedition and a naval battle against the Barbary pirates, occurred during these months but would not reach Jefferson until later in the year. Even so, in these pages he conducts the work of government, both in Washington and at Monticello, granting pardons, seeking permission from the Spanish government for a scientific expedition along the Red River, and working on plans for offshore patrols by armed U.S. vessels. He also pays the artist Gilbert Stuart $100 “for drawing my portrait.”

“There’s a lot about what is going on in the United States,” says James McClure, who has been working on the project since 1996 and been its general editor since 2014. “It’s not all centered on the mind of Jefferson.”

In these pages he conducts the work of government, both in Washington and at Monticello, granting pardons, seeking permission from the Spanish government for a scientific expedition along the Red River, and working on plans for offshore patrols by armed U.S. vessels.

In all, the Jefferson Papers project will contain approximately 20,000 letters written by Jefferson and another 30,000 received by him, as well as all his public papers, including many early drafts. The volumes published so far add up to 34,858 pages, McClure says. The first 45 volumes are also available online.

Although the Jefferson Papers project now turns out roughly a volume per year, each of the recent volumes covers only a few months of Jefferson’s life. Presidents are very busy people, even during the Federal era, and Jefferson received a huge amount of incoming correspondence, much of which is included in order to put into perspective what he was reading and what may have influenced his thinking.

The project was able to keep up the pace during COVID, McClure says. He and his staff of nine are always working ahead, as well. Volume 47, which covers July to November 1805, is now in production, and Volume 48 (November 1805 to March 1806) is in the final review and revision stage. Editors are even beginning their work on Volumes 50 and 51, which will not appear in print for a few years.

Former Princeton librarian Julian Boyd conceived of the project in 1943 while working on the Thomas Jefferson Bicentennial Commission. The first volume appeared in 1950 and Boyd remained at the helm until his death in 1980. McClure is only the fifth general editor in 80 years. In 1999, the project was divided and the responsibility for publishing papers from Jefferson’s retirement years (1809-1826) was transferred to the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, which also runs Monticello. Eighteen volumes of that series have been published so far, also by the Princeton University Press.

Access to clear, legible copies of Jefferson’s writings, along with the copious and informative notes that are the heart of each volume, has been indispensable to historians, political scientists, and others. “This edition will be of lasting value to our nation for generations to come,” President Harry Truman declared when the first volume appeared. As author Gordon Wood, winner of both the Pulitzer and Bancroft prizes, told PAW in 2003, “This project is not going to have to be done again.”

But when will it be done? For a time, it was hoped that the Jefferson Papers project, which began during the bicentennial of Jefferson’s birth, would be finished by 2026, the bicentennial of his death. Even after spinning off Jefferson’s post-presidential papers, McClure says that the final letters will not be published until around 2030. He declines to guess how many volumes they will eventually encompass.

No responses yet