The Sound of Patience

Calvin Van Zytveld ’19 is a gifted musician whose life changed when he became blind three years ago

The first thing Calvin Van Zytveld ’19 shows a visitor to his home is the back lawn — or, rather, what used to be the back lawn. What once was a typical suburban yard in Grand Rapids, Michigan, is now a miniature farm. There are two 24-by-26-foot garden beds where he and his parents tend lettuce and spinach; rows of peppers, beans, tomatoes, and peas; and root crops like onions and sweet potatoes. Nearer the house is an herb garden; on the far side of the yard, a coop with six chickens.

He squats down to inspect a young pepper plant, fingering it gently. Rising, he says: “Gardening forces you to be patient.”

Patience has been an essential aspect of Van Zytveld’s life over the past three years. At Princeton, he was a gifted music student: principal cellist in the University Orchestra, a member of chamber music groups, recipient of the Edward T. Cone Prize, one of the department’s highest honors. He loved playing and composing and knew he wanted a career in music, even if he wasn’t sure exactly what that career would be.

But just months after graduation, in his first year of graduate school at the University of Michigan, his vision started to blur. Soon, he would be blind, his sight lost to a hereditary disorder that would force him to reconsider his life’s path.

Suddenly, cello performance no longer made sense: An orchestral musician needs to follow the directions of the conductor and sight-read music scores. He turned his attention to learning to live independently without sight. In October 2021, he was in a Michigan training center, learning to work with his new guide dog, when at dinner he met Kevin Bell, a gardener who was also blind. Bell recommended a book, The New Organic Grower; that night, Van Zytveld began to devour an audio version. He had never gardened as a sighted person, but the more he heard, the more he liked the idea of it. Excited, he told his parents about Bell and gardening. Two days later, his mother sent a video of his dad rototilling the backyard.

“For the last few years, there have been a lot of dead ends,” Van Zytveld says, explaining the attraction. “I’d get excited about something, then I’d realize that some portion is inaccessible to me.” Gardening sounded different. Despite its many obstacles, he could do it mostly independently, as Bell had proven. And it appealed to his sense of art and experimentation, with a seemingly infinite number of plant varieties, combinations, and ways to tweak processes and techniques.

“And so far,” he says, “it’s wonderfully suited to the slower pace of my life.”

“It took a really long time for me to even get out of that denial phase. It felt like a very strange dream. It didn’t register as something that was permanent, that would have lasting impacts for every part of my life.”

— Calvin Van Zytveld ’19

It took about nine months from the time he began losing his vision for Van Zytveld to get an accurate diagnosis: Leber Hereditary Optic Neuropathy, known as LHON. It’s a rare mitochondrial DNA disease, meaning it is inherited through the maternal line, explains neuro-ophthalmologist Nancy J. Newman ’78, a professor at the Emory University School of Medicine and a world leader in LHON research.

All children of a mother with an LHON mitochondrial DNA point mutation will inherit it, though many carriers will never lose their sight, explains Newman. Males are more likely to show symptoms of LHON in their lifetimes: About 25% of those who have the mutation will have vision loss, compared to 5% to 10% of females. Men are also more likely to show signs of the disease at a younger age, usually at 22 to 25 years old, while vision loss strikes women at a mean age of 30 or 31, Newman says.

Some people with Van Zytveld’s particular point mutation spontaneously recover some sight, Newman says. He has not. He has some peripheral vision and some color perception, but he cannot identify letters on an eye chart; his vision loss is measured by counting the fingers held up by an examiner seated nearby. He does all his work nonvisually.

There is much that remains unknown about his disease: what causes sudden vision loss in only some of those at risk, why it happens more frequently to males than females, why some people improve. There is no known cure, Newman says.

I met Calvin Van Zytveld several years ago, when he was a Princeton sophomore and I was a middle-aged woman who wanted to return to playing cello, an instrument I’d abandoned decades before. He gave me lessons. Week after week, in a basement practice room in the Woolworth Center, he suffered through my rusty playing, demonstrating how to move the bow or improve my phrasing. One day, he invited me to hear him perform in an early-music ensemble. Of course, I went. I loved hearing him play.

My lessons ended when he went to London to study at the Royal College of Music for a semester in his junior year. We didn’t stay in touch, though I imagined I would see him on a concert stage one day. Then, last December, I received a note from him on LinkedIn, explaining how his life has changed over these past few years. In his new profile photo, he appeared with his guide dog, Wake.

He told his story in a social-media post in October: “On this day, two years ago, I was at the ER at Michigan Medicine, trying to get answers on why I was rapidly going blind. … At first, I could just put my face a bit closer to my screen as I worked, and then I had to start using a magnification tool, and then that stopped working for me. … . These days I am able to see large objects, but not faces or text (unless it’s very large and close to my eyes). My vision should remain stable, though.

“I miss being able to read music, see facial expressions, see individual leaves on trees. … But there’s still so much to enjoy: my guide dog Wake, my crazy gray tabby Earnest T.K. Hobbes, my amazing friends, my loving family, beautiful fall weather. …

“Talking about going blind still makes me feel a bit ill,” he wrote, “but I do love talking about my life as a blind person.”

While the exterior of the Van Zytveld home in Grand Rapids is dominated by the garden, the interior reflects the interest Calvin’s had for nearly his entire life: music. He began piano lessons when he was 4 years old; at 8, he took up the cello. Music runs in the family. His dad, a musicologist and college euphonium player, is a public-school music teacher who introduced him to Stravinsky, Mahler, and Renaissance choral music, which remain “some of my most treasured things to listen to,” he says. His mother performs and teaches violin; his brothers play trombone and piano. The home is filled with musical instruments, and when the children were younger, the family played music together.

Van Zytveld considered going to a conservatory, but the loans he would have needed seemed daunting. Princeton offered a first-rate musical education without the burden of loans. He began to compose, completing his first piece during his semester in London. With his adviser, Steven Mackey — who is best known on campus as a rock guitarist but is also an expert on early music — he studied 16th-century counterpoint, coming to think of it as “weightlifting for composers.” Mackey recalls advising him as “like working with a grad student — in some ways, even better. He was less entrenched in dogma. He had a prodigious appetite for music. Calvin had all the freshness and openness of an undergrad, but the expertise, passion, and commitment of a graduate student.”

He was pursuing two master’s degrees at Michigan: one in composition, one in cello performance. He was home in Grand Rapids in April 2020 — the university had sent students packing at the beginning of the COVID pandemic — and was working furiously on a piece of music. Taking a break, he went skateboarding one afternoon and noticed a blind spot in his left eye. Then, late that summer, he was working on an editing project for a cello professor and found that the text on the computer screen was blurry. By the time he moved back to Ann Arbor in September 2020, he couldn’t see well enough to complete a group of songs without the help of a friend. Doctors couldn’t explain his vision problems, but most didn’t seem too worried, suggesting they resulted from eye strain or dry eyes.

Soon he could no longer drive safely. In October 2020, he returned to the Kellogg Eye Center in Ann Arbor and was seen in the emergency room, then admitted. It was an excruciating time for the family: His father had recently been hit by a car, and to Van Zytveld, the period “felt kind of apocalyptic.” It was his mother, Elizabeth, who first identified his condition. By that point, the family had done research and had heard about LHON, and she was wondering if this might be what caused her son’s vision loss. She called a maternal cousin who was “on the cusp of legal blindness.” Had the cousin been diagnosed with LHON? Yes, she said; she had the disease. Van Zytveld had genetic testing, and the diagnosis was confirmed that month.

He left graduate school and spent several months learning how to perform tasks without the use of vision. His LinkedIn profile describes the period from October 2020 through January 2022 matter-of-factly, listed under a heading of “Career transition.” Another cousin who is blind (though not from LHON) taught him to read in Braille — whose creator, Louis Braille, was also a cellist. He spent a few months at a rehabilitation center in Kalamazoo, learning mobility and life skills. And after three weeks in October 2021 at a center of Leader Dogs for the Blind, he returned home with Wake, a sweet and reliable Lab who would become his constant companion.

“It took a really long time for me to even get out of that denial phase. It felt like a very strange dream. It didn’t register as something that was permanent, that would have lasting impacts for every part of my life,” he recalls. “In that time between starting to go blind and really realizing that I was blind, I learned Braille, got started with assistive technology, learned adaptive kitchen skills, all this great stuff that made the realization that I was blind maybe not quite as horrible, because I was already able to do a lot of these things by that point.”

In early 2022, he returned to Princeton to collaborate on a ballet for the music department with Pilar Castro-Kiltz ’10, who worked as a director, dancer, and choreographer before founding a small management consulting firm. He had arranged to meet his former adviser, Mackey, for lunch in the basement dining room in Prospect House. He was a few minutes late — which was unusual, Mackey recalls — then walked in with his guide dog. He had not mentioned his blindness to his professor. Mackey was shocked, but he quickly realized that little else about his former student had changed: “He’s got this nonentitlement, nonresentful, grateful attitude, and he always has. He’s lost his sight, not his positive presence. And that’s what separated him from his cohort when he was fully sighted.”

Most people, Van Zytveld notes, know blindness only as a metaphor. For him, it’s a fact of life that has required uncovering untapped strengths and finding a new place in the world. “Before going blind, I would have thought that the most horrible thing about blindness was not being able to see things — the general experience would be so debilitating. But that part is not really troubling to me. I think the hard thing is the loss of efficacy in a world that is largely not designed for blind people.”

He recalls once seeing a blind man using a white cane in the New York City subway and feeling almost a sense of panic for that person, yet now he believes it would be easier to live independently in the chaos of New York City than in a quiet, car-centric suburb like his neighborhood in Grand Rapids.

He often thinks about the “Bridges” engineering class he took at Princeton, in which students built structures out of dry pasta. The course focused on efficiency, economy, and elegance in design — big ideas that took on personal meaning when he became blind and considered issues such as neighborhood walkability and transit. “I get frustrated when I realize how limited my independence really is. You know, I walk every day with Wake; in one direction I walk a mile and change and get to a strip mall that has a Turkish coffeehouse and a Starbucks and a grocery store, and in the other direction I can walk to a bakery. That’s also like 1.3 miles. … That’s it. If I didn’t live with my parents here, it would be very limiting.”

Van Zytveld says he is lucky that today’s technology offers tools to make the barriers of daily living more surmountable. Screen readers allow him to make full use of his computer and smartphone. He knows the layout of the kitchen, where he uses a talking meat thermometer and a device that alerts him when hot liquids reach a certain level, so they don’t overflow. Because he has some remaining vision, he uses a cutting board with one white side and one black side, choosing the side that provides the best contrast. In his garden, where he spends his mornings, he uses hand implements, getting close to the ground so he can better make out what he is doing. But he points out that much of a gardener’s work is tactile, even for those who are sighted: The products of a gardener’s labor are often hidden beneath the ground or among the abundant leaves of bushes.

When you’re with him, it’s easy to forget he cannot see. His limited peripheral vision helps him get around. He navigates his parents’ house without a misstep. On the drive home from lunch — Wake sitting politely at his feet on the passenger side of the car — he gives perfect directions. “It’s that yellow one,” he says, as I am about to drive past his house.

His greatest challenge, he says, has been reimagining his career. He realized early in his blindness that he would not have the cello career he had thought about. He used to love studying new scores and learning new music, but now he cannot see the notes on the page. Still, he completed some compositions, including a choral anthem for the Grand Rapids Choir of Men and Boys that was performed in December. He finished the ballet he was working on at Princeton with the help of his brother William, dictating pitches, note durations, and articulations so William could transcribe it. Sometimes Calvin sang what he wanted or played it on a keyboard. He still envisions a career in music, but instead of performing, he’s thinking about a life in academia, or something altogether different.

He knows he has been insulated from the greatest challenges of blindness because of his Princeton education, his skills, his access to technology, his network, and the support of his parents. Most blind people, he says, are not as lucky, and are more likely than other people to be under- or unemployed and to live in poverty.

After losing his vision, Van Zytveld took a part-time job as an accessibility consultant with More Canvas Consulting, the firm founded and led by his collaborator in music, Castro-Kiltz. “Calvin had the idea that digital accessibility was more than accommodation. He wanted to go one step further” and think of the experience a person with vision loss would have on a website, says Castro-Kiltz.

For example, she says, a person with vision loss often relies on something known as alt text: invisible descriptions of images that are read aloud on a screen reader. Castro-Kiltz explains that a screen reader might come to a picture and read aloud: “Picture: Dog in a meadow.” She continues: “But is it just a dog in a meadow? Or is it a golden retriever jumping with joy for a red ball, flying through the air in a meadow of yellow flowers on a sunny day? Can we give some consideration to the aesthetic potential of the website and the experience of the receiver of this information?” That’s the thinking of an artist. “I felt it was important to create a platform, an opportunity for Calvin to explore and express this intersection of service, business, and creativity,” she says.

At More Canvas, Van Zytveld set up accessibility protocols and led a team to revamp and create websites that people with vision impairments could use freely. He began a podcast about accessibility — his first interview was with Bell, the blind organic gardener who had prompted him to transform his backyard. And he developed recommendations for how companies can better collaborate with blind employees. On Zoom meetings, for example, people often write comments in the chat mode, which cannot be accessed by those without vision. More Canvas instituted a new rule: no more writing in chat during staff meetings.

For Van Zytveld, the job opened yet another window into the barriers blind people face in employment and made him an advocate for others with disabilities. He acknowledges that he never thought about challenges facing disabled people before: “I was contributing as much as anyone to this ignorance before it came to affect me.”

Nancy Newman’s quest to find a treatment for LHON goes on. Researchers have seen some modest improvements in vision from the use of an antioxidant called idebenone (which Van Zytveld takes) and from gene therapy, but these are not cures and cannot prevent the disease, she says.

A hero for LHON families and doctors is Lissa Poincenot ’78. In 2008, her then-19-year-old son, Jeremy, began to lose his vision from LHON. Poincenot deployed the research skills she had developed at Princeton and her MBA in marketing, and she and Jeremy raised money and spoke publicly about the disease. She created a website, LHON.org, to share positive stories and support and — perhaps most important — to provide information about clinical trials and make it easier for people to opt in. Until then, finding people to enroll in trials had been a huge obstacle, says Newman.

Poincenot wants people to know that LHON “is not an individual issue, but a family issue.” Four years ago, at 26, her daughter Julie found that her vision was blurring; she, too, has vision loss from LHON. Both Poincenot siblings lead happy, successful lives: Julie in the hotel industry, and Jeremy as an inspirational speaker and international champion in blind golf.

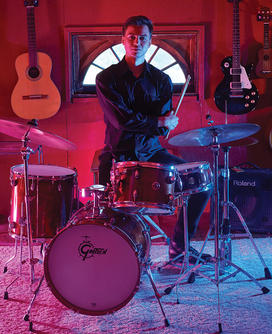

For Van Zytveld, the summer months were full. Rather than hunkering down to learn new scores, he spent hours learning German, a language required by his graduate program. He gardened. He read more. He had taught himself to play the drums and had a standing drumming gig at a nearby church. He wrote program notes for the Great Lakes Chamber Orchestra and delivered a preconcert lecture. He did not want to become blind, he says, but losing his vision has opened space for other interests.

He did not play the cello for a long time. The sense of loss was too great. But over the summer, he began playing again, though with “very modest aspirations.” He performed at a Grand Rapids chamber music festival that he had founded and now directs with two friends, playing the cello part for arrangements of violinist Fritz Kreisler’s Liebesleid (Love’s Sorrow) and Liebesfreud (Love’s Joy). “It felt like a homecoming of sorts to play with old musician friends again,” he says.

This month, Van Zytveld will begin Ph.D. studies in musicology at Stanford. University employees who work on document accessibility can convert textbooks and journal articles into file types that he will be able to read. Music scores will be rendered as XML files; he will be able to listen to individual instrumental parts. He has requested living space near the music building, since the campus is large and he can no longer ride his bike. He needs a place spacious enough for his “medical equipment”: Wake.

Stanford is often called “The Farm,” because it was established on Leland and Jane Stanford’s stock farm in Palo Alto, and the founding grant decreed that “a farm for instruction in agriculture” should continue on university land. That seems appropriate for Van Zytveld, whose excitement for gardening and farming has only increased. He might work on a dissertation about the hymn-singing traditions of Colonial America and the relationship between early farming practices and music-making. If he is not a professor, or even if he is, he says, he hopes to bring together farming and music.

When I visited him in May, Grand Rapids was enjoying a spell of gorgeous spring weather. He was content: “I have time to garden, time to go for long walks with my amazing dog. … In a weird way, I’ve been pretty happy quite a lot.”

He would be leaving the backyard garden to his parents. He hoped it would not increase their workload but thought they were hooked and might even expand it. It was the beginning of the season; roots were still taking hold, sprouts were just breaking through the newly overturned earth.

There would be a lot of growing over the next few months.

Former PAW editor Marilyn Marks *86 is a freelance writer and editor.

0 Responses