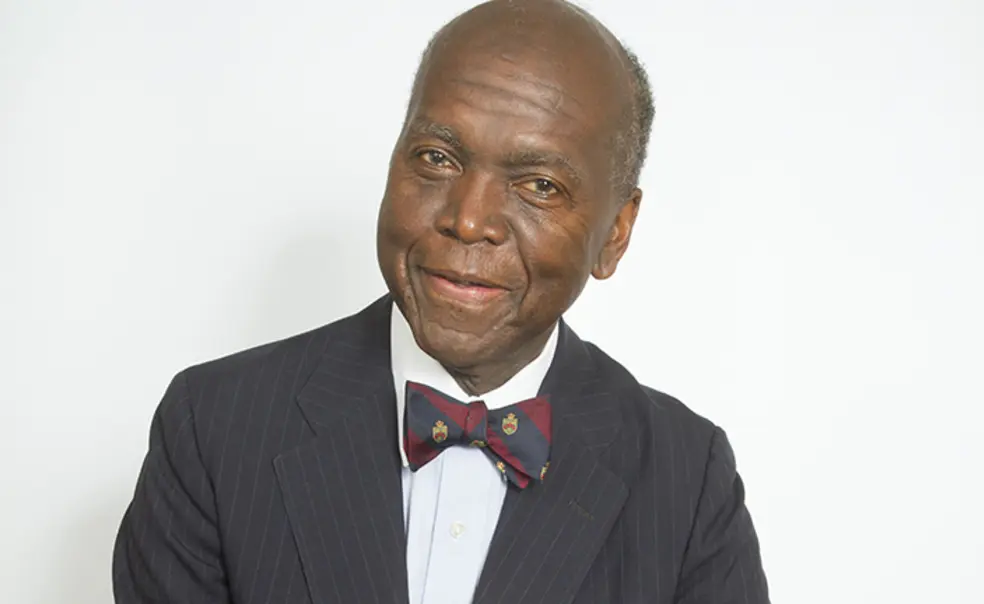

After 50 Years in Admissions, David Evans *66 Leaves Behind a More Diverse Harvard

“We realized that the old system wasn’t addressing the changes that were necessary”

Not long after he left Princeton, David Evans *66 found himself writing to the nation’s top colleges.

Schools had recently integrated, and Evans, then living in Huntsville, Alabama, discovered that often meant moving Black students into white schools where they had little or no support. Bright minds doing well academically weren’t always getting the college counseling they needed. So Evans stepped in.

He started as a volunteer tutor, but discovered the students needed more. “I wrote to 60 or 70 colleges with my background and said, ‘I think some of these people may qualify for your institution,’” Evans remembers. The first two he counseled got into Princeton’s Class of 1973. Others were accepted at Smith, Brandeis, Columbia, Stanford, Dartmouth, Morehouse, Amherst, Chicago, and more. MIT and the College Board reached out to talk to Evans about working for them.

Then Harvard came calling.

Evans wasn’t a higher education professional. He was an electrical engineer with IBM, a subcontractor on the Saturn-Apollo project. But Harvard’s dean of admissions was persistent.

“I said, ‘I’m a country boy from Arkansas.’ He said, ‘I’m a country guy from Utah,’” Evans says, recalling their back-and-forth. In 1970, Evans moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts.

This summer he’s retiring from Harvard as a senior admissions officer, and departing with a new accolade: The Harvard Alumni Association awarded him the prestigious Harvard Medal for “extraordinary service to the University,” according to the university’s official news outlet.

“I am trying to shift into the proper mindset to grasp the significance of this honor,” Evans wrote in an email, “and how much it would have meant to my late sharecropper/domestic-worker parents.”

Evans grew up in Phillips County and describes it as among the poorest places in Arkansas. “We didn’t know how bad off we were, and maybe that was a blessing,” he says. His grandmother was born into slavery in February 1865. His parents died when he was young, but his second oldest sister withdrew temporarily from college, found work as a substitute teacher, and took over as head of the household. If she hadn’t, the children likely would have gone into the “system,” Evans says. “We were able to continue existing as a family.”

His mother and grandmother believed in “two sources of magic”: religion and education. Evans says he hasn’t kept up with the religion as much, but “I’ve devoted my life to the education part of it.”

He went to Tennessee State and then Princeton, where — a Harvard historian later told him — he was the first African American to get an advanced degree in electrical engineering. He arrived at Harvard during the Black Power movement and a push to diversify higher education. Following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the number of Black students doubled at most Ivy League schools “overnight,” he says.

In the past 50 years, at least 17 times as many Black students have been admitted to Harvard as in the previous 334, Evans says. He’s quick to credit many people for making it happen, and Harvard for letting him work outside the box.

For example, instead of waiting for candidates of color to appear, admissions told its network of alumni volunteers across all 50 states to seek them out by talking to local school counselors and combing local newspapers. In 1971, at Princeton, Evans helped found the Association of Black Admissions and Financial Aid Officers of Ivy League and Sister Schools. “It was a Black group that said we will not only do our regular job, but also serve as emissaries to keep inclusion and diversity in the minds of our colleagues,” he says.

Harvard “allowed me to improvise. That has to be done to recruit and enroll and keep persons who have not been in a place like Harvard and Princeton,” Evans says. “We realized that the old system wasn’t addressing the changes that were necessary.”

2 Responses

Demetrius Nelson

5 Years AgoCongrats to David Evans

As the vice president of the African American Alumni Council of Georgia College & State University (GCSU) I want to congratulate on the worthy honor that has been bestowed on you. I want to thank you for your work that is truly a great blueprint for African Americans like myself and the council that I am part of, who are trying hard to accomplish what you did at our predominantly white institution. Who knows, maybe you can come speak to our council, our college president and his cabinet, and admissions about what it takes to get more African Americans at our fine liberal arts university. Your wisdom would be a gem to hear.

Joycelynn Nelson, Ph.D.

5 Years AgoThank You and Congratulations

I just want to simply pay homage to Mr. Evans and the university's willingness to find a solution to systemic issues in the admissions process! This has changed the trajectory of generations of well qualified candidates that may have been overlooked. Thank you Mr. Evans and congratulations on your retirement.