Alan Blinder ’67 Talks of Taking Stock of the Presidential Candidates

Although the presidential primary races for both political parties seem pretty much decided by now, the market guessed long ago that George Bush would harness the Big Mo and win the Republican nomination. Now the market has made Bush the odds-on favorite to win in November.

The market is a simulated stock exchange that operates out of the economics department’s conference room, on the second floor of Dickinson Hall. Continuing a tradition that was started twelve years ago, four professors issued “stock certificates” for all of the presidential contenders early last fall and set up a system by which the shares could be bought and sold. This market was an instructive academic exercise, they reasoned, because share prices would fluctuate – at least in theory – along with political fortunes. They also figured that it would be more fun than a typical election-year office pool.

The professors issued forty shares for each contender, at an initial cost of one dollar per share. About twenty faculty members and graduate students in the economics department and Woodrow Wilson School bought them. (Undergraduates were excluded from joining the market.) In November, each share of the president-elect’s stock will be worth ten dollars – a potential four-hundred-dollar windfall for anyone who corners the market in the victorious candidate. This is a winner-takes-all enterprise: even shares that are held in the runner-up will be worthless after the election. As in the real stock market, supply and demand determine the price of each share, which is posted on a chalkboard.

In late April, for example, the holders of George Bush stock were willing to relinquish their shares for between $5.50 and $6.70 apiece; this was indicated on the chalkboard in a column marked “Ask.” Others were willing to buy Bush stock for between $4.50 and $5.00; they listed their offers under the “bid” column. Potential buyers and sellers write their initials next to each offer, and if a buyer and seller agree on a transaction price for a share, this is recorded in the column marked “Last.” Just like the stock market.

According to economics professor Alan Blinder ’67, one of the four “market regulators” who issued the stock, the price of each share reflects the probability that a candidate will be elected, at least in the opinon of the market. Bush’s shares, for example, recently had an “Ask” price of six dollars. This means that the owner of the shares believes that there is a six-in-ten chance that Bush will win the election, since six dollars is 60 percent of the possible payoff per share. Jesse Jackson’s shares, in contrast, have a current asking price of twenty cents per share and an offer to buy at fifteen cents.

“Even after the Michigan primary, we didn’t see much movement in Jackson prices,” Blinder says. “He opened at ten cents a share and went as high as thirty cents, from a 100-1 longshot to 33-1. But the market is nonetheless reflecting the view that the large numbers of votes he’s received do not significantly increase the probability that he will be elected.”

Blinder got the idea for issuing stock in candidates when he was teaching at Stanford in 1974. He and some friends organized a pool to bet on the date on which President Nixon would resign. “It was never a question of if, only when,” he says. When Blinder returned to Princeton, he applie the same idea to political campaigns, and under his leadership the economics department issued stock in candidates during the 1976 and 1980 elections. (In 1984, Blinder says, the result was such a foregone conclusion that the game was abandoned for lack of interest.)

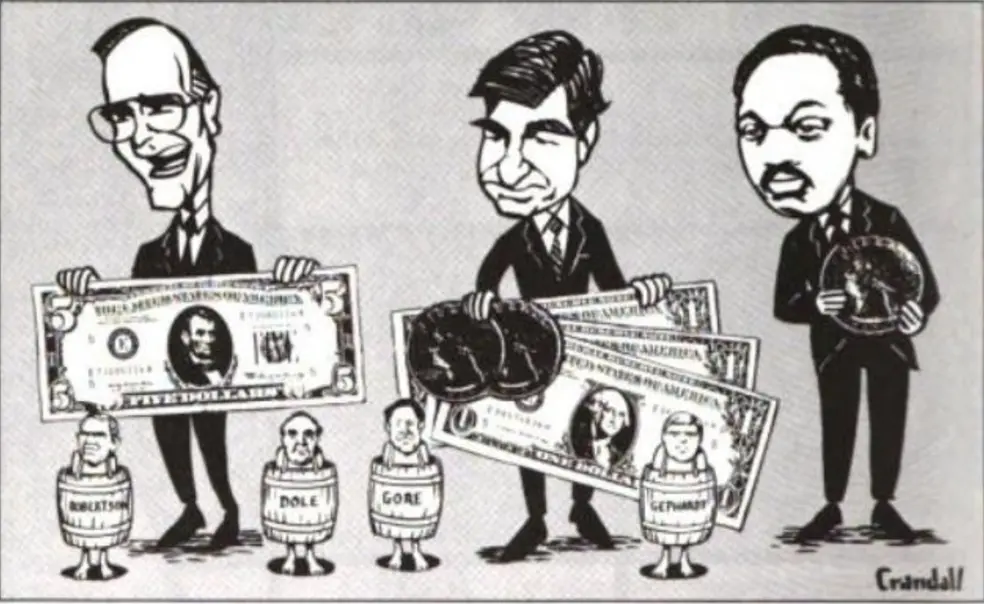

This year, Blinder and his fellow agents issued stock in a total of ten candidates. On the Republican side, they created shares of Bush stock and Robert Dole stock, as well as shares in “Other Republican,” a category that covered the ill-fated campaigns of Alexander Haig, Pat Robertson, Pete DuPont, and other dark horses. The Democratic side was represented by shares in Michael Dukakis, Richard Gephardt, Paul Simon, Albert Gore, Jackson, Gary Hart, and “Other Democrat.” Early in the campaign, when on clear front-runner had emerged in the Democratic race, speculation that a brokered convention would lead to the nomination of an unannounced candidate upped the prices of the “Other Democrat” shares. Thirty primaries later, these shares have dropped precipitously in value.

Astute traders could have made a killing on Dole stock. After the Iowa caucuses, which were won by the Kansas senator, Dole stock soared to as high as three dollars a share. A few weeks later, after Dole’s disappointing loss in the New Hampshire primary, his stock plummeted; now it is as worthless as Gephardt or Gary Hart stock. Albert Gore’s shares rose sharply in value after his success in the Super Tuesday primaries, leveling off around a dollar apiece, and there they stayed for almost two months. The he pulled out, and now Gore stock isn’t even for sale any more. (In late April, Blinder and his fellow market regulators suspended all trading in the stocks of the candidates who had pulled out of the race.)

The only legitimate bet on the Democratic side, at least in the opinion of the market, is Dukakis. People are bidding $3.50 for a share of his candidacy (up from $2.75 before the New York primary), but no one is selling. In these conditions, Blinder as the market regulator will sometimes step in and offer some of his own shares for sale, in this case for $4.00. “It’s important to keep the market open,” he says. Even so, the supply curve of shares in the likely nominees grows increasingly inelastic as the election draws nearer. And what about shares in the also-rans? “If you’re holding a lot of Gephardt stock,” Blinder says, “you might as well paper your walls with it. In theory, everything has a price, but I doubt you’d find someone willing to buy Gephardt stock for a tenth of a cent a share.”

This was originally published in the May 4, 1988 issue of PAW.

No responses yet