Albert Einstein Answer His Mail

A new book collects the letters he wrote to children, students, relatives, and strangers about politics, religion, patriotism, psychoanalysis, music, and cats.

Helen Dukas became Einstein’s secretary in 1928 and, since his death in 1955, has been a trustee of his literary estate and archivist of his papers. Banesh Hoffmann, professor of mathematics emeritus at Queens College and the City University of New York, did his graduate work at Princeton under Oswald Veblen.

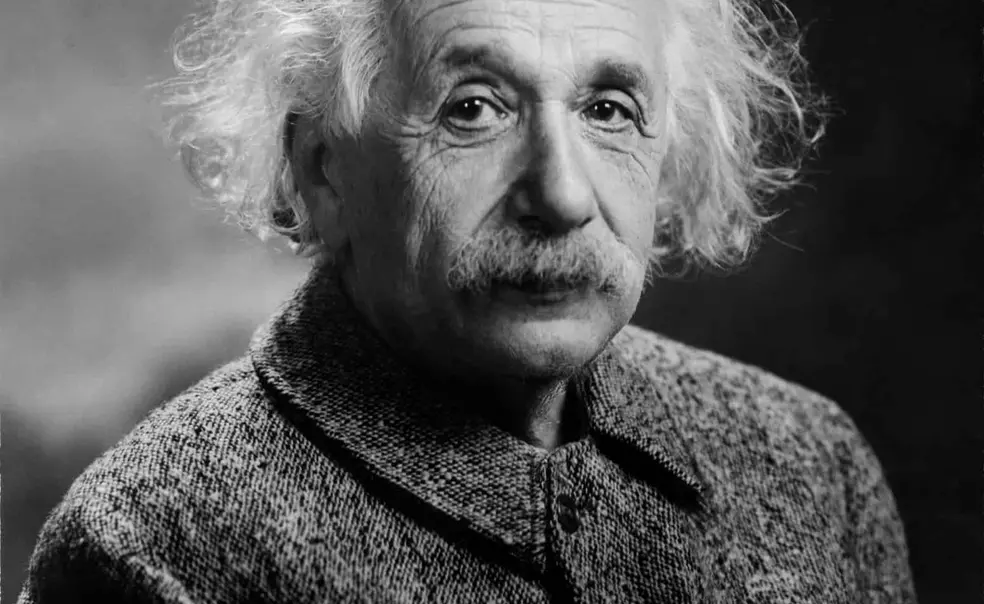

Albert Einstein was not only the greatest scientist of his time but also by far the most famous. Moreover, he answered letters. And it is this combination that makes the present book possible.

Unlike our previous book, Albert Einstein: Creator and Rebel, this one is not a biography and does not explain Einstein’s ideas. It has no chapters, no table of contents, no index, and, at first glance, no plan for structure. It consists, for the most part, of quotations from hitherto unpublished letters and the like that Einstein wrote without thought of publication. There is no need to describe them further here since they speak eloquently for themselves.

Here is an excerpt from a letter the Einstein wrote to his sister in 1898, when he was a student in Zurich (he addressed her in his letters as “Dear Sister” much as, later, he would address Queen Elizabeth of Belgium as “Dear Queen”):

“What oppresses me most, of course is the [financial] misfortune of my poor parents. Also it grieves me deeply that I, a grown man, have to stand idly by, unable to do the least thing to help. I am nothing but a burden to my family. ... Really, it would have been better if I had never been born. Sometimes the only thought that sustains me and is my only refuge from despair is that I have always done everything I could within my small power, and that year in, year out, I have never permitted myself any amusements or diversions except those afforded by my studies.”

The following letter, also written by Einstein to his sister Maja, belongs to a later time. It is dated 31 August 1935. Much has happened since those early days in Berlin. Einstein is now in Princeton, striving to generalize his general theory of relativity so that it will become a unified field theory. At the same time, all his instincts cry out to him to be wary of developments in the quantum theory that most other physicists accept with equanimity. But his preoccupation with the problems of physics does not blind him to what is going on in the outside world. He writes to his sister as follows:

“As for my work, the going is slow and sticky after a promising start. In the fundamental researches going on in physics we are in a state of groping, nobody having faith in what the other fellow is attempting with high hope. One lives all one's life under constant tension till it is time to go for good. But there remains for me the consolation that the essential part of my work has become part of the accepted basis of our science.

The big political doings of our time are so disheartening that in our generation one feels quite alone. It is as if people had lost the passion for justice and dignity and no longer treasured what better generations have won by extraordinary sacrifices. ... After all, the foundation of all human values is morality. To have recognized this clearly in primitive times is the unique greatness of our Moses. In contrast, look at the people today! …”

On 28 October 1951 a graduate student in psychology sent a beautifully worded letter to Einstein in Princeton asking for advice. The student was an only child and, like his parents, Jewish though not orthodox. A year and a half before, he had fallen deeply in love with a girl of the Baptist faith. Knowing the pitfalls in a mixed marriage, and the unintended wounds that could be inflicted by the thoughtless remarks of others, the couple had mixed socially with friends and acquaintances and found that their love was able to withstand the stresses. The girl, un-prompted, had expressed a willingness to convert to Judaism so that their children would have a more homogeneous family life. While the young man's parents liked the girl, they were frightened of intermarriage and gave voice to their objections. The young man was torn between his love for the girl and his desire not to alienate his parents and cause them lasting pain. He asked whether he was not right in believing that a wife takes precedence over parents when one ventures upon a new mode of life.

Einstein drafted a reply in German on the back of the letter. The reply may very well have been sent in English, but only the German draft is in the Einstein Archives. Here is a translation of it:

“I have to tell you frankly that I do not approve of parents exerting influence on decisions of their children that will determine the shapes of the children's lives. Such problems one must solve for oneself.

However, if you want to make a decision with Which your parents are not in accord, you must ask yourself this question: Am I, deep dow, independent enough to be able to act against the wishes of my parents without losing my inner equilibrium? If you do not feel certain about this, the step you plan is also not to be recommended in the interests of the girl. On this alone should your decision depend.”

A fifth grade teacher in Ohio found that most of his students were shocked to learn that human beings are classed as belonging to the animal kingdom. He persuaded them to compose letters asking the opinions of great minds and, on 26 November 1952, he sent a selection to Einstein in Princeton hoping that Binstein would find time to reply. This Einstein did, in English, on 17 January 1953, as follows:

“Dear Children,

We should not ask "What is an animal" but "What sort of a thing do we call an animal?" Well, we call something an animal which has certain characteristics: it takes nourishment, it descends from parents similar to itself, it grows, it moves by itself, it dies if its time has run out. That's why we call the worm, the chicken, the dog, the monkey an animal. What about us humans? Think about it in the above-mentioned way and then decide for yourselves whether it is a natural thing to regard ourselves as animals.”

A child in the sixth grade in a Sunday School in New York City, with the encouragement of her teach-er, wrote to Einstein in Princeton on 19 January 1936 asking him whether scientists pray, and if so what they pray for. Einstein replied as follows on 24 January 1936:

“I have tried to respond to your question as simply as I could. Here is my answer.

Scientific research is based on the idea that everything that takes place is determined by laws of nature, and therefore this holds for the actions of people. For this reason, a research scientist will hardly be inclined to believe that events could be influenced by a prayer, i.e. by a wish addressed to a supernatural Being.

However, it must be admitted that our actual knowledge of these laws is only imperfect and fragmentary, so that, actually, the belief in the existence of basic all-embracing laws in Nature also rests on a sort of faith. All the same this faith has been largely justified so far by the success of scientific research.

But, on the other hand, every one who is seriously involved in the pursuit of science becomes convinced that a spirit is manifest in the laws of the Universe-a spirit vastly superior to that of man, and one in the face of which we with our modest powers must feel humble. In this way the pursuit of science leads to a religious feeling of a special sort, which is indeed quite different from the religiosity of someone more naive.”

It is worth mentioning that this letter was written a decade after the advent of Heisenberg's principle of indeterminacy and the probabilistic interpretation of quantum mechanics with its denial of strict determinism.

In Dresden a government official, who spoke of himself as a politician and an Adlerian psychotherapist, was planning a book to be based on psychoanalyses of important people. In this connection, on 17 January 1927, he wrote to Einstein in Berlin to ask if he would allow himself to be psychoanalyzed. It is not known if an answer was actually sent, but, on the letter, in German in Einstein's handwriting, is the following draft of a reply:

“I regret that I cannot accede to your request, because I should like very much to remain in the darkness of not having been analyzed.”

On 17 July 1953 a woman who was a licensed Baptist pastor sent Einstein in Princeton a warmly appreciative evangelical letter. Quoting several passages from the scriptures, she asked him whether he had considered the relationship of his immortal soul to its Creator, and asked whether he felt assurance of everlasting life with God after death. It is not known whether a reply was sent, but the letter is in the Einstein Archives, and on it, in Einstein's handwriting, is the following sentence, written in English:

“I do not believe in immortality of the individual, and I consider ethics to be an exclusively human concern with no superhuman authority behind it.”

In 1954 or 1955 Einstein received a letter citing a statement of his and a seemingly contradictory statement by a noted evolutionist concerning the place of intelligence in the Universe. Here is a translation of the German draft of a reply. It is not known whether a reply was actually sent:

“The misunderstanding here is due to a faulty translation of a German text, in particular the use of the word "mystical." I have never imputed to Nature a purpose or a goal, or anything that could be understood as anthropomorphic.

What I see in Nature is a magnificent structure that we can comprehend only very imperfectly, and that must fill a thinking person with a feeling of "humility." This is a genuinely religious feeling that has nothing to do with mysticism.”

In Princeton, shortly after his arrival there, Einstein was asked by a freshman publication, The Dink, for a message. He responded with these words, which were published in December 1933:

“I am delighted to live among you young and happy people. If an old student may say a few words to you they would be these: Never regard your study as a duty, but as the enviable opportunity to learn to know the liberating influence of beauty in the realm of the spirit for your own personal joy and to the profit of the community to which your later work belongs.”

There is in the Einstein Archives a letter dated 5 August 1927 from a banker in Colorado to Einstein in Berlin. Since it begins "Several months ago 1 wrote you as follows," one may assume that Einstein had not yet answered. The banker remarked that most scientists and the like had given up the idea of God as a bearded, benevolent father figure surrounded by angels although many sincere people worship and revere such a God. The question of God had arisen in the course of a discussion in a literary group, and some of the members decided to ask eminent men to send their views in a form that would be suitable for publication. He added that some twenty-four Nobel Prize winners had already responded, and he hoped that Einstein would too. On the letter, Einstein wrote the following in German. It may or may not have been sent:

“I cannot conceive of a personal God who would directly influence the actions of individuals, or would directly sit in judgment on creatures of his own creation. I cannot do this in spite of the fact that mechanistic causality has, to a certain extent, been placed in doubt by modern science.

My religiosity consists in a humble admiration of the infinitely superior spirit that reveals itself in the little that we, with our weak and transitory understanding, can comprehend of reality. Morality is of the highest importance—but for us, not for God.”

A Chicago Rabbi, preparing a lecture on "The Religious Implications of the Theory of Relativity," wrote to Einstein in Princeton on 20 December 1939 to ask some questions on the topic. Einstein replied as follows:

“I do not believe that the basic ideas of the theory of relativity can lay claim to a relationship with the religious sphere that is different from that of scientific knowledge in general. I see this connection in the fact that profound interrelationships in the objective world can be comprehended through simple logical concepts. To be sure, in the theory of relativity this is the case in particularly full measure.

The religious feeling engendered by experiencing the logical comprehensibility of profound interrelations is of a somewhat different sort from the feeling that one usually calls religious. It is more a feeling of awe at the scheme that is manifested in the material universe. It does not lead us to take the step of fashioning a god-like being in our own image- a personage who makes demands of us and who takes an interest in us as individuals.

There is in this neither a will nor a goal, nor a must, but only sheer being. For this reason, people of our type see in morality a purely human matter, albeit the most important in the human sphere.”

Einstein was an ardent violinist, his violin being his inseparable companion. The composers of the eighteenth century were his favorites. He loved the music of Bach and Mozart. Beethoven he admired rather than loved, and he felt less rapport with later composers.

With fame came an intense and often annoying interest in all aspects of his life. So when a German illustrated weekly in 1928 sent him a questionnaire in Berlin about Johann Sebastian Bach it is not surprising that Einstein ignored it. The editor waited a while and then, on 24 March 1928, sent a second request. This time, on the very same day—the mails were faster in those days—Einstein answered brusquely as follows:

“This is what I have to say about Bach's life work: listen, play, love, revere—and keep your mouth shut.”

Some ten years later a more searching questionnaire about Einstein's musical tastes arrived from a yet different source and this one he answered in more detail. The questionnaire seems to have been lost, but the questions on it can be inferred more or less from Einstein's responses, which bear as date only the year 1939:

“(1) Bach, Mozart, and some old Italian and English composers are my favorites in music. Beethoven considerably less—but certainly Schubert.

(2) It is impossible for me to say whether Bach or Mozart means more to me. In music I do not look for logic. I am quite intuitive on the whole and know no theories. I never like a work if I cannot intuitively grasp its inner unity (architecture).

(3) I always feel that Handel is good—even perfect—but that he has a certain shallowness. Beethoven is for me too dramatic and too personal.

(4) Schubert is one of my favorites because of his superlative ability to express emotion and his enormous powers of melodic invention. But in his larger works I am disturbed by a certain lack of architectonics.

(5) Schumann is attractive to me in his smaller works because of their originality and richness of feeling, but his lack of formal greatness prevents my full enjoyment. In Mendelssohn I perceive considerable talent but an indefinable lack of depth that often leads to banality.

(6) I find a few lieder and chamber works by Brahms truly significant, also in their structure. But most of his works have for me no inner persuasiveness. I do not understand why it was necessary to write them.

(7) I admire Wagner's inventiveness, but I see his lack of architectural structure as decadence. Moreover, to me his musical personality is indescribably offensive so that for the most part I can listen to him only with disgust.

(8) I feel that [Richard] Strauss is gifted, but without inner truth and concerned only with outside effects. I cannot say that I care nothing for modern music in general. I feel that Debussy is delicately colorful but shows a poverty of structure. I cannot work up great enthusiasm for something of that sort.”

On 1 February 1954 a correspondent cited Einstein's urgings that people be prepared to go to prison if necessary in order to preserve free speech and to oppose war. The correspondent went on to say that his wife, seeing what Einstein had written, pointed out that he had not wasted any time in leaving Germany when the Nazis came to power instead of staying on to speak out and risk being jailed. She contrasted this with the behavior of Socrates, who refused to leave his country but stayed to "fight it out." She also remarked that it was easier for well-known people to speak out than it was for lesser men.

On 6 February 1954 Einstein replied in English as follows (For some reason he omitted in the English version a remark in the German draft, a translation of which is added here enclosed in square brackets.):

“Thank you for your letter of February 1st. I think what your wife has said is pretty well to the point. It is true that a man who enjoys some popularity is in a less precarious situation than someone unknown to the public. But what better use could a person make of his "name" than to speak out publicly from time to time if he believes it necessary?

The comparison with Sokrates is not quite to the point. For Sokrates Athens meant the World. I, however, never identified myself with any particular country, least of all with the German state with which my only connection was my position as member of the Prussion Academy of Sciences [and the language, which I learned as a child].

Although I am a convinced democrat I know well that the human community would stagnate and even degenerate without a minority of socially conscious and upright men and women willing to make sacrifices for their convictions. Under present circumstances this holds true to a higher degree than in normal times. You will understand this without explanation.”

On 3 August 1946 the Chief Engineer American cargo boat wrote a charming letter to Einstein in America telling of an incident on board. The Boatswain and the Carpenter had found a half-starved kitten ashore in Germany, taken it on board, adopted it, and fed it rich food in abundance so that it filled out and flourished and became much attached to its foster parents. But it scratched a seaman who tried to play with it, and he cried out that the cat was crazy. The Boatswain defended the reputation of the kitten saying it was crazy like Einstein, who had had the good sense to leave Germany for the United States. As a result, the kitten was formally given the name "Professor Albert Einstein" by sailors who could not distinguish "relativity" from "kinship."

On 10 August 1946, Einstein replied in English as follows:

“Thank you very much for your kind and interesting information. I am sending my heartiest greetings to my namesake, and also from our own tomcat who was very interested in the story and even a little jealous. The reason is that his own name “Tiger” does not express, as in your case, the close kinship to the Einstein family.

With kind greetings to you, to my namesake’s foster parents, and to my namesake himself,…”

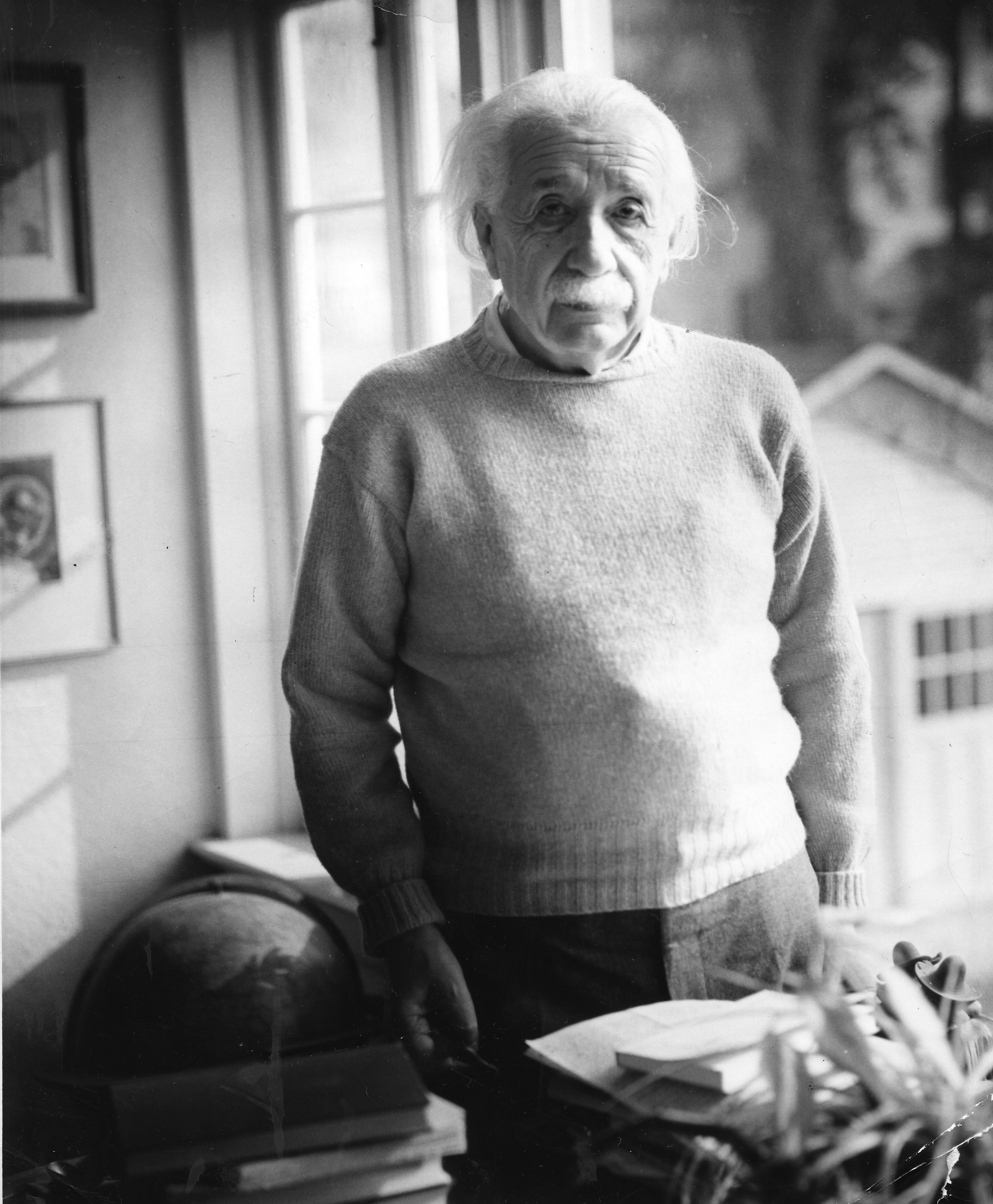

Einstein was notoriously unconcerned about his attire, which was often quite sloppy. In 1955, early in March, the children in a fifth grade class in an elementary school in the state of New York became aware not only of Einstein's existence but also of the fact that his seventy-sixth birthday would fall a few days hence. With the help of their teacher, they sent Einstein a letter on Io March wishing him many happy returns, and with the letter they sent a present consisting of a tie clasp and a set of cuff links. It was to be Einstein's last birthday.

On 26 March 1955 Einstein wrote back in English as follows:

“Dear Children,

I thank you all for the birthday gift you kindly sent me and for your letter of congratulation. Your gift will be an appropriate suggestion to be a little more elegant in the future than hitherto. Because neckties and cuffs exist for me only as remote memories.”

This was originally published in the March 12, 1979 issue of PAW.

No responses yet