Is the Proposed Endowment Tax Another Cash Grab?

A ‘meteor is about to hit’ higher education as Republicans look to increase the tax on endowments

It sounds preposterous.

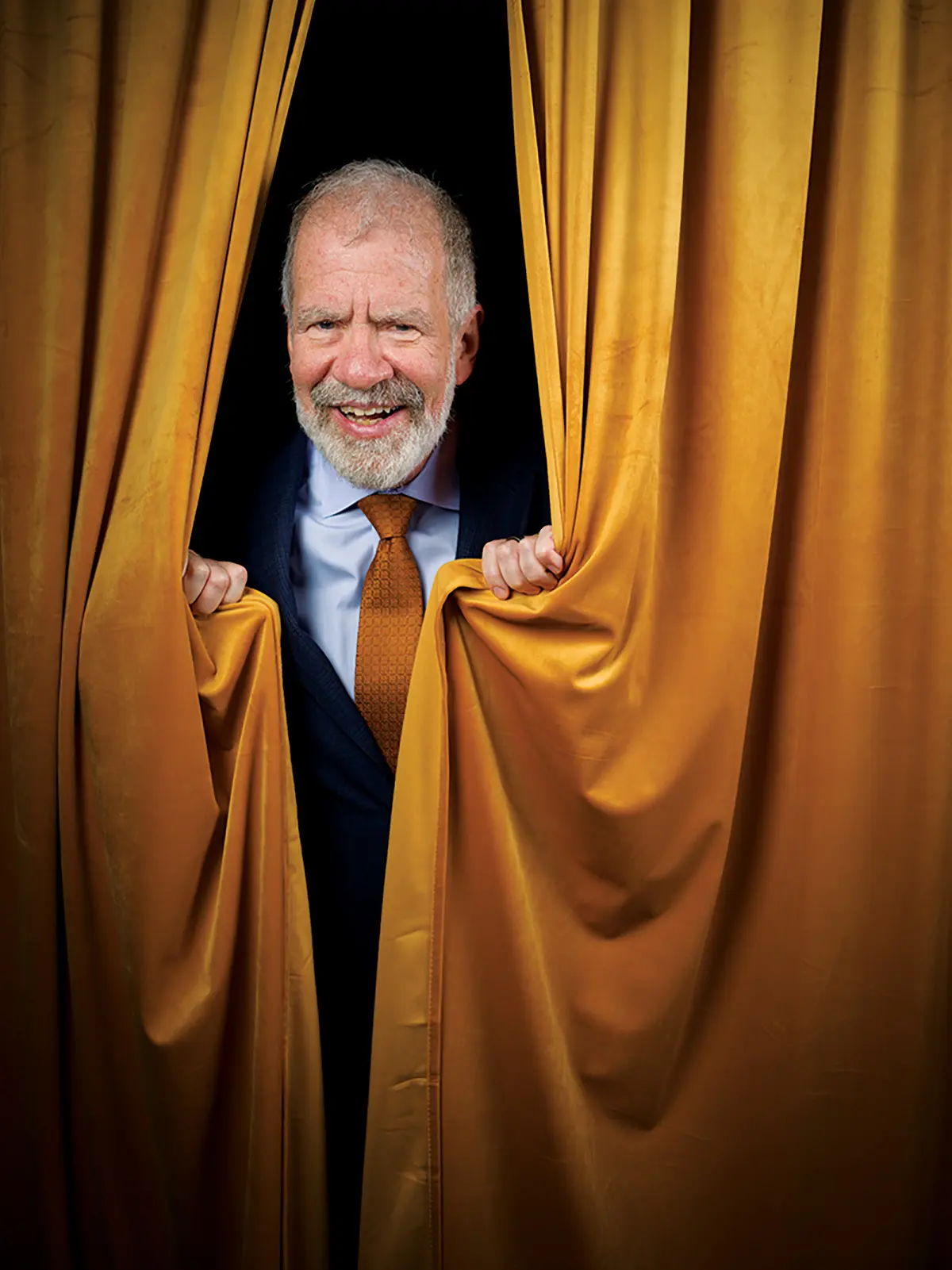

President Christopher Eisgruber ’83 warned in his annual State of the University letter in January that absent additional fundraising and income from investments, if Princeton University keeps spending 5% or more each year from its $34.1 billion endowment — which is its customary practice — it “will be gone in 20 years or less.”

Unless the world turns upside down, that is not actually going to happen. Princeton will keep fundraising and the endowment should keep producing returns, if not at the almost 10% a year rate of the past two decades. At the same time, the University will keep tapping the endowment, as it did this fiscal year for $1.7 billion as part of its $3.1 billion operating budget, which covers everything from student aid and faculty salaries to opening new labs and mowing the lawns.

Princeton relies on its endowment for an unusually large share of its budget. “We ask a lot of it,” says deputy provost Richard Myers, including allowing the University to break into promising new areas of research such as artificial intelligence and precision health care that can pay big dividends for the country’s economy. “If you take X million dollars out of the endowment today, that money’s gone from the endowment forever,” and with it the potential for future breakthroughs, he says.

But there’s a snake in that grass and it’s already biting. In 2017, Uncle Sam took the unprecedented step of challenging the tax-exempt status of higher-education institutions by imposing a 1.4% excise tax on the investment earnings of private colleges and universities with the most wealth, including Princeton. In 2023, 56 institutions paid $380 million to the U.S. Treasury. These revenues go into the government’s general funds; they aren’t earmarked to help students pay for college, which was the idea when lawmakers first eyed taxing wealthy colleges in the late 2000s. Also, the excise tax does not expire; it is part of the permanent tax code.

Now, spurred by Republicans who want to punish “woke” colleges dominated by what President Donald Trump calls “Marxist maniacs,” lawmakers have their knives out to slice even deeper into these endowments, and more colleges may be caught in the net.

One proposal would hike the excise tax to 14% on net investment income. Rep. Troy Nehls, R-Texas, wants to boost it to 21%, the same as the corporate tax rate. And then-Sen. and current Vice President JD Vance pushed in 2023 to make the excise tax 35%, which in Princeton’s case could mean hundreds of millions of lost dollars each year. Vance, a Yale Law School graduate, said it was “insane” how much universities charged in tuition and likened them to “hedge funds with a university attached.” Democrats blocked that bill. Trump, another Ivy League (Penn) product, railed against big university endowments when he first ran for president in 2015 and stepped up the attack in his recent run.

Republicans have made college faculty and leaders a target in their culture wars, even before universities’ mishandling of protests over the war in Gaza and the rise of antisemitism on campuses sparked calls to cut off federal aid to institutions that didn’t crack down and cost the presidents of Harvard and Penn their jobs. Attempts by former President Joe Biden to forgive a large chunk of the $1.7 trillion mountain of student loan debt have also fueled their anger.

They have introduced more than a score of bills not only to raise the endowment excise tax, but actually to confiscate a chunk of the corpus of the biggest endowments, not just earnings. Sen. Tom Cotton, R-Ark., has touted his “Ivory Tower Tax Act” that would take 1% a year out of these endowments. Or there’s his “Woke Endowment Security Act” that would impose a one-time 6% tax on full endowments, costing Princeton $2 billion.

The current excise tax hits colleges with at least 500 undergraduates and endowments of $500,000 or more per student. While Harvard, Yale, and Stanford boast larger endowments, none has endowments-per-undergraduates as large as Princeton’s $4 million.

College leaders have their hands full dealing with the raft of executive orders and actions that Trump let fly in his first days back in office, including his efforts to quash diversity programs, a short-lived freeze on grants, and an immigration crackdown that could threaten “Dreamers” and international students.

“There’s the misperceptions about how we use the money, that it’s just a piggy bank that you can go and take money out of anytime you want. That’s not how it gets used.”

— Phillip B. Levine *90

Wellesley College professor of economics

Phillip B. Levine *90, a Wellesley College professor of economics and authority on endowments, says he believes presidents aren’t raising alarms about the endowment tax loudly enough. “They don’t recognize a meteor is about to hit,” he says.

The huge returns that almost all college endowments booked in 2021 — 31% on average and nearly 47% for Princeton — fed antipathy toward the sector.

“All of a sudden there were these massive amounts of money. People thought, ‘Wow! These places are now very wealthy, with billions of dollars sitting in the bank,’” says Levine. “And then there’s the misperceptions about how we use the money, that it’s just a piggy bank that you can go and take money out of anytime you want. That’s not how it gets used.”

Eisgruber and his development office, which raised $67 million from alumni and others last year, deal with those misperceptions all the time.

In the State of the University letter, Eisgruber wrote that “worrisome taxation proposals … result partly from misunderstandings of what endowments do. Even sympathetic Princetonians sometimes ask why the University must continue to raise money when its endowment is so large.”

People “sometimes assume that an endowment is like a savings account and that universities can ‘dip into it’ to pay for unexpected needs or special projects,” he wrote. But it is “nothing like a savings account. It is more like a retirement annuity that must provide income every year for the remainder of the owner’s life.”

Not everyone agrees that taxing big university endowments is a bad thing. Gregory Conti, an associate professor in Princeton’s Department of Politics, recently penned an argument for taxation that appeared in Compact magazine and The Chronicle of Higher Education under the headline, “Hate Endowment Taxes? Reform the University.”

Conti, a political theorist and senior fellow at the conservative Manhattan Institute, wrote that historically, “large endowments are not the normal mechanism for funding education” and no other countries’ universities have these outsized endowments. Skepticism toward them is not an “intrinsically right-wing proposition, even if that is the direction from which hostility is coming at present.”

But Conti criticized what he described as the liberal tilt, ideological conformity, and administrative bloat at universities and said, “If they wish to continue to enjoy their privileged position, colleges need to do much better at living up to the values that legitimize them in the first place.” Conti acknowledged that endowments support world-leading research at U.S. universities. “To even the most hardened critic of higher education, this is a very strong argument,” he wrote.

The conservative author and columnist George F. Will *68 called the excise tax “astonishingly shortsighted” when it was first imposed. “Great universities are great because philanthropic generations have borne the cost of sustaining private institutions that seed the nation with excellence,” he wrote.

More than 70% of the financial aid Princeton provides comes from the endowment, according to the University. While tuition this year is $62,400 and room and board $20,250 on top of that, 62% of all undergraduates and 71% of first-year students receive financial aid. Most families with incomes up to $100,000 pay nothing, which Levine says makes Princeton “one of the cheapest schools in the country.”

Princeton has been a leader among top universities in opening its gates wider to more students from lower ends of the income scale. It made national headlines in 2001 when it stopped requiring students take out loans in their aid packages. Some do, but almost 90% graduate debt-free, according to the University.

While the Ivies and other elite schools are still considered bastions of the privileged, Princeton has tripled the percentage of students who qualify for federal Pell Grants, given to students from low- or modest-income families. It was 7% in the Class of 2008. It’s 22% for the Class of 2028.

Of course, Princeton is not alone in bristling against the excise tax. It hits small, excellent liberal arts colleges as well.

Carleton College in Minnesota pays $1 million in excise taxes from its $1.2 billion endowment. That’s “the equivalent of 10 full scholarships,” Carleton president Alison Byerly wrote in a Washington Post op-ed in January. More than half its 2,000 undergraduates receive aid.

Some proposals in Congress — including one that Rep. Brendan Boyle, D-Pa., pushed in the past — would spare wealthy colleges from paying the excise tax if they provided sufficient financial aid. Princeton would easily pass that bar.

But there are other bills that could impact higher education, even disqualifying some universities from federal student aid programs or cutting what they can charge for administering big research grants. “We do see this as the nose of the camel,” says Steven M. Bloom, assistant vice president of government relations at the American Council on Education, which along with the Association of American Universities (an organization of top research institutions that Eisgruber chairs) is an influential voice in Washington on higher education policy.

Although Princeton’s endowment has grown solidly for decades, that is not a given. After the banner year in 2021, it declined by 1.5% in 2022 and 1.7% in 2023 before a 3.9% gain in 2024, which was half the Ivy League average.

Princeton’s investments include big sums — $14 billion last year — in private equity funds and venture capital that don’t always hit home runs. Since it taps the endowment each year to cover a majority of its budget, these drawdowns can equal or surpass earnings. The $34.1 billion endowment currently stands $3.6 billion below its 2021 peak of $37.7 billion, Eisgruber said in his letter. “At a university, endowment payout must cover a portion of the operating budget every year for the rest of the university’s existence — and we hope Princeton will live for centuries,” Eisgruber wrote.

More than half — 55% — of the endowment is restricted to allow only the income generated to be tapped and 70% to be used solely for the donor’s purpose, such as scholarships or endowing a faculty chair.

There is no comparable tax on the endowments of other 501(c)3 organizations. Private foundations are required to spend 5% each year for charitable purposes. Donors might be surprised or even dismayed to learn that returns from the tax-deductible $1,000 or $10,000 or even $1 million they gave years ago is now subject to taxes.

Republicans say they plan to use the budget process called reconciliation to push through the tax cuts and other priority spending bills. They can do so in the Senate with a simple majority. Higher education experts in Washington are girding for two reconciliation bills, with the tax cuts and the excise tax issue perhaps not coming up until late in the year.

Another way to hit higher education and students would be to tax Pell Grants and all other scholarships and fellowships, which could raise $54 billion over 10 years while making it harder for students to pay for college.

Raising the excise tax “isn’t a done deal,” says Andrew Grossman, chief tax counsel for the Democrats on the House Ways and Means Committee. “The Republicans have very slim margins, especially in the House. It really only takes one or two members to put their foot down and stymie a provision like this.”

“Nothing is done until it’s done,” says Liz Clark, the National Association of College and University Business Officers’ vice president for policy and research.

Meanwhile, Eisgruber says he intends to keep making the case against these “threats of confiscatory or punitive taxation” and trying to explain “to the Princeton community, lawmakers in Washington, and the American public … how endowments work and the public benefits they create.”

Christopher Connell ’71 is an education writer in Washington, D.C.

9 Responses

Andrew H. Browning ’71

9 Months AgoTax-Exempt Status Benefits All Citizens

I just read the letter from Blair Perot ’87 in the May PAW. I am confused. Perot correctly reminds us that tax-exempt status is provided to “entities that society believes are serving the public good.” In fact, according to the federal tax code, section 501(c)(3), nonprofit organizations that exist exclusively for educational purposes are tax-exempt, and thus throughout the history of the IRS, Princeton and other schools have not been taxed: religious schools, secular schools, military schools, vocational schools, boys’ schools, girls’ schools, nursery schools, universities — none of them. But my understanding falters when I read Perot’s next sentence: “Entrenched leftists don’t get to decide what the ‘public good’ is — society gets to decide that, and society (which yes, does unfortunately include those peons) is now about to make very clear how they currently value Princeton’s recent contributions to societal division and dysfunction.”

For 40 years after graduation I was perhaps the only member of my class whose career was in high school teaching, history and English. As a history teacher, I taught my students that one thing Americans had always — always — agreed to be taxed for was the support of schools, not so that their children could get good jobs but because educated citizens in a republic can better govern themselves. We have never taxed schools — not religious schools, secular schools, military schools, boys’ schools, girls’ schools, nursery schools, universities, none of them.

As an English teacher, I expected my students to write clearly, so that any reader could understand them, but I don’t understand what Perot means by “entrenched leftists.” Princeton? 163 years of IRS administrators? All the Congresses that have written the tax codes? And I don’t understand what is meant by “those peons”; perhaps I am one of them? perhaps Perot is? or is this a wittily ironic allusion to Elon Musk? But anyone can figure out who Perot means by “society”—certainly not the 64% who just told the AP/NORC poll that they appreciate the public benefit of colleges, and probably not the members of Congress who should be making our laws but no longer seem to be. No, Perot means the single person who now governs our nation by executive order. My high school history students could tell you what to call government by a single person, and it’s not “society.”

Leslie Hajdo *77

9 Months AgoWhat Is the Limit to Princeton’s Growth?

The article on endowments (“Is the Proposed Endowment Tax Another Cash Grab?,” March issue) is not surprising to anyone in academics, but it misses an important objection: the runaway growth of programs, administrators, salaries, and facilities.

In 1972, my stipend as an incoming graduate student was $2,300 annually. The USA CPI calculator equates this to $17,595 today. Graduate students are now paid about $43,000 annually. In 1994-95, Princeton’s operating budget was $525 million. This is equivalent to 1.1 billion today. The current operating budget is approaching $3 billion.

Like any “charity,” no amount of money is ever enough. Princeton is competing to be the best, and other universities are growing faster than inflation, too. But what is the limit to growth?

Molly Greene *93

11 Months AgoChallenging a Problematic View of Campus Protests

Perhaps I shouldn’t have been, but I was shocked by Christopher Connell ’71’s casual remark, almost in passing, about the “rise of antisemitism on campuses.” This is how a highly inflammatory and problematic opinion becomes established “fact.” Are college campuses suddenly swarming with antisemites? As an active participant in the Palestinian encampment at Princeton last spring, I saw no antisemitism at all, just protest against Israeli policies in Gaza and American support for same. The historical record belies those who automatically see antisemitism in criticism of Israel. From the beginnings of the Zionist movement, some of the biggest supporters of Israel have been antisemitic. Arthur Balfour, the author of the Balfour Declaration, to give just one, but very consequential, example, was afraid of eastern European Jews migrating en masse to Britain. Theodore Herzl, the founder of modern Zionism, was well aware of this. He wrote in his diaries: “the anti-Semites will become our most dependable friends, the anti-Semitic countries our allies.” It is long past time for people to educate themselves about the relationship between support for Israel and antisemitism.

Rob Slocum ’71

11 Months AgoEndowments Serve the Public Interest

You can see why people would be skeptical of college endowments. What some of these journalists should do together with their routine rankings is to investigate schools’ service to their communities and to the country. Things like research, George Will *68’s idea of training leadership — and Princeton’s very aggressive approach to financial aid. Yes, and also the fact that Princeton has almost doubled its undergraduate headcount since my undergraduate days. (Alumni like to complain about too many buildings on campus. Well, this is one reason.) Harvard has maintained the same graduating class size that it had 55 years ago, but it has a vast array of institutes serving the public interest, with as many employees as on the academic side. Stories like these need to be told before anyone jumps to too many conclusions about whether the tax-advantaged status of educational finance is well-deserved or not.

James Steichen *14

11 Months AgoEndowment’s Role in the Student Experience

Thank you for this excellent overview of the proposals being weighed by the administration regarding endowment taxation and the negative effects they could have on the student experience, including financial aid. As a graduate alum I know my debt-free Ph.D. would not have been possible without the resources of the endowment. The entire Princeton community needs to understand how extreme and detrimental these measures would be, and I am glad PAW is using its reach to raise awareness.

Blair Perot ’87

11 Months AgoTax-Exempt Status Is a Privilege

Tax-exempt status is not a right, it is a privilege reserved for entities that society believes are serving the public good.

Entrenched leftists don’t get to decide what the “public good” is — society gets to decide that, and society (which yes, does unfortunately include those peons) is now about to make very clear how they currently value Princeton’s recent contributions to societal division and disfunction.

Anybody who is shocked by an endowment tax has had their head purposely buried in the sand. Princeton was clearly warned by the first 1.4% endowment tax and did not reverse track one iota over the last eight years. Leadership hubris did this to Princeton.

Peter Seldin ’76

11 Months AgoExternal Pressure Could Spark Change

With their lack of viewpoint diversity and their administrative bloat, the universities have brought these problems on themselves. Maybe this external pressure will serve a very good objective.

Bob Hall ’67

11 Months AgoTaxation Hypocrisy

Republicans are vehemently against wealth taxes, except when a perceived liberal entity is the target. Typical hypocrisy.

Jack Warner ’68

1 Year AgoGovernment Profit and Loss

It would be interesting to see a “government p & l” for the University, comparing fees and other expenses paid to the federal government vs. federal research grants and other funding to the University.