ON A SUNNY DAY in July 2019, in the Mayacamas Mountains east of Santa Rosa, California, Whitney Fisher ’99 headed up through a wooded hillside after a morning’s work in the fields. She was dressed in her standard uniform: jeans, work boots, pink-and-white plaid shirt, straw hat dangling from a cord around her neck. She followed a path up to a brown, board-and-batten building and went around back, where a teak table was set under mulberry trees for the Fisher Vineyards weekly lunch for senior staff.

It was the kind of idyllic setting the words “wine country” evoke. The farm-to-table lunch featured chicken and vegetables grilled outdoors and an ample salad. The lunch crew — Whitney’s mother, brother, and sister, as well as the heads of hospitality and marketing, the cellar master, and a few guests — reminisced about how the Fishers had transformed a century-old sheep ranch into a producer of high-quality wines. Then they debated the theories of the state’s top enology school, the follies of “lifestyle vintners,” and Supreme Court decisions about interstate commerce, among other subjects. Finally, mini chocolate cakes with crème fraiche and strawberries, made by Whitney’s mother, Juelle, were served in honor of the cellar master, one of five brothers in the Vega family, as integral to the winery as the founding family itself.

The Fishers are among a small number of Princetonians who have taken their liberal-arts degrees and their MBAs and applied them to a fetching industry. Their wineries are scattered as far east as New York and as far south as Chile, but most are located in Northern California.

Barely three months after that lunch, the wine industry was shaken when wildfires struck; the Kincade fire came dangerously close to the Fishers’ property. The following January, the first case of coronavirus in the state was reported; soon, schools across the state were shuttered, restaurants and bars were emptied, and their wine sales were gone, too. COVID-19 raged through communities of farmworkers.

Then, in late summer 2020, wildfires again swept across Northern California. The August Complex “gigafire” burned more than 1 million acres, an area larger than the state of Rhode Island. By September, thick smoke trapped by a layer of fog in the Bay Area caused a day described by many as resembling a nuclear winter. Last September, the Glass Fire caused mass evacuations and burned the hillsides surrounding Fisher Vineyards, sparing the family home and the winery — just barely.

Never had the wine industry seemed more fickle. Yet established family wineries headed by Princetonians survived. They did so through luck, grit, family spirit, and innovative marketing. Not only did they manage to keep putting out cases and cases of fine wines, they make for a fascinating story of small businesses that keep an eye on the past while reinventing themselves for the future.

FOR THE MOST PART, wineries run by Princetonians fall into the loose category of “family winery.” Josh Greene, ’81, editor and publisher of Wine & Spirits, defines a family winery as a privately held company in which a clan brings its values and intergenerational dynamics to bear.

“At one end of the spectrum are the mega-corporate family wineries, like Gallo in California and Boisset in France,” says Greene. Midsize family wineries include Wente Vineyards, where Christine Wente ’97 is a fifth-generation winegrower, and Marimar Estate, where Cristina Torres ’10 works at a Sonoma satellite of the family’s 150-year-old Spanish brand, Torres.

Smaller in scale are what Greene calls “artisanal” wineries, which would include most of the wineries owned by Princetonians, like Fisher in California, Lakeshore Winery in New York, and Kingston Family Vineyards in Chile. They also include labels that own neither vineyards nor a winery but rather enter into long-term agreements with growers, control a specific tract of land, hire a winemaker, and market their premium wines, such as Moone-Tsai winery, headed up by Larry Tsai ’79. Then there are, Greene says, “bootstrap efforts” — tiny wineries that will themselves into existence with a grand vision, little money, and a lot of expertise.

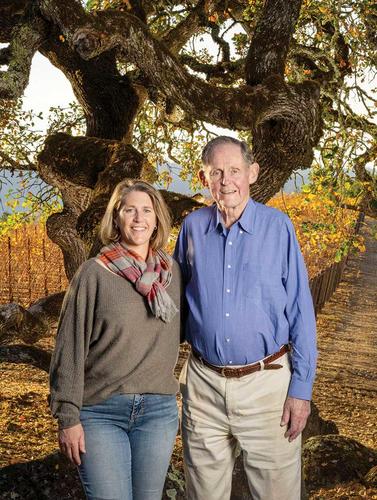

Fred Fisher ’54 might have been called a bootstrapper in 1973, when he planted his first vines. One of six “damn independent” kids in a family descended from a founder of Fisher Body Co. in Detroit, Fred majored in basic engineering at Princeton, got an MBA at Harvard, and joined the Army. On a short leave, he discovered wine at Lago di Garda in Italy, he says, spreading his lanky frame over a teak chair under the mulberry trees. “I said, ‘This is the life.’”

After two years in Detroit at General Motors, he left his industrialist, auto-industry background behind, took off for San Francisco, and worked as a management consultant. “My sister Jane and her husband, Tom, lived just down the hill,” Fisher notes, employing a salty blend of words and sentences and a voice that recalls Jimmy Stewart in timbre. “I saw this land, and thought, ‘That’s where I want to be.’” He bought some land from his sister in 1973.

“I grew up with the philosophy that you learn things by doing,” Fred says. “I thought, by God, this will be interesting. You can learn.”

There was a lot to master. “I was learning how to drive a tractor down there,” he says, pointing to a spot below. “I hit a patch of mud. In Detroit, you hit a patch of mud and you accelerate. I drove that tractor so deep in the mud it took two weeks to get it out.”

Wine-drinking may seem glamorous, but winemaking is far from it. The making of the fermented-fruit-in-liquid-form starts in the field, with careful curation of the grapes and a harvest of the prime fruit. After the removal of stems and leaves, grapes are crushed into pulp, or “must.” Then comes fermentation in tanks, when yeast converts the grape juice into alcohol. The cellar master oversees activity within the cellar, and the winemaker keeps close tabs, constantly tasting the developing wine. After aging in casks, for a few months or a few years, the libation is bottled, sold, and consumed — or, in the case of reds, aged even longer.

“It was just the two of us,” remembers Fred’s wife, Juelle, who had worked in the investment business, of the first vintage, in 1979. “Fred did the planting and harvesting. I shoveled the stuff out of the tank. We wanted to touch the whole grape.”

Grapes had to be paired with the right landscape. This European notion of “terroir” is one that California vintners have imported; it refers to how a region’s climate, soils, and terrain affect taste. So the Fishers had to master more than just tractors and mud. An inhospitable patch of land called the Wedding Vineyard, because that’s where Fred and Juelle had married, features three feet of clay-heavy topsoil over rock. “It gave us such fits,” Juelle says. “We couldn’t get the berries through the antiquated must pump, and the tannins were harsh.” According to Fred, the key was to pick as late as possible and to shift from inoculated to natural yeasts, which produce a slower, gentle fermentation. The result? A cabernet sauvignon lauded by a reviewer as a “broody, virile” wine.

Each of the three Fisher children has an affinity for a different aspect of running a vineyard. Whitney, the eldest, is head of winemaking and farming. Her brother, Rob, is the general manager, and her sister, Cameron, handles marketing.

Whitney Fisher grew up thinking she’d be a scientist and planned to major in molecular biology. A summer job in a lab changed that; she switched to American history. She took a job at a wine-industry mergers-and-acquisitions firm in the late 1990s, when Australia, South Africa, and New Zealand were all coming on the scene. “But it was a desk job,” she says, “and I’m a country girl.”

With her parents at a pivotal time in the business, she came back to the family vineyard. “I did everything — designed the website, helped the winemaker, replanted vines with the vineyard crew,” she says. “I spent the harvest of 1999 in the cellar with hoses and barrels, and I never left.”

It has not always been easy. She works alongside the crews — “whether replanting in the fields or repacking in the winery. My father is right — you end up knowing so much more if you’re there, working.” She learned Spanish and pushed herself, as “the boss’s daughter,” to outwork everyone else.

At a family winery like Fisher, the word “family” extends to those beyond the clan; Whitney says the camaraderie has helped the business survive the challenges of 2020, even strengthening the bonds. When the fires came, workers and family members helped keep them at bay, bolstering a “sense of shared destiny.” When COVID-19 made it necessary to cut costs, everyone gave up something but no one lost their livelihood; when vaccinations became available, the entire workforce of 22 people opted for the shots. Meanwhile, the team found new opportunities, Whitney says, like a successful “Zoom on women and wine.” Though farm workers were hit badly by COVID-19, “We have emerged out of the pandemic with every single employee still with us,” Whitney says in a phone interview in spring 2021. “That was our goal.”

FOR COURTNEY KINGSTON ’92, being part of the family team means being at her kitchen table in a two-story tract home near Palo Alto, California, pandemic or not; her co-workers are in Princeton, New York City, and the Casablanca Valley in Chile. She travels to Chile about every other month (when there’s no pandemic raging) and uses WhatsApp to meet with far-flung relations.

Courtney is head of sales and marketing for Kingston Family Vineyards. She describes herself as a “misfit”: an MBA who works on a family farm; an international businesswoman who is also a suburban mom.

After graduating from Princeton with a degree in Latin American studies, Courtney moved to San Francisco and worked at Deloitte & Touche as a consultant for California wineries. She entered Stanford Business School and then moved to high-powered tech jobs. At 30, knowing the corporate grind wasn’t for her, she decided to help the farm.

Soon Courtney was helping her family find new purpose for the 7,500-acre ranch in Chile where her father, Michael ’62, had grown up. Founded by her great-grandfather, a miner who had left Michigan for Chile in the early 1900s, the ranch was supplying 5 percent of all the fresh milk to the capital city of Santiago, but it was subject to the vagaries of commodity pricing. The Casablanca Valley was developing a reputation for crisp white wines. Courtney started talking with her brother Tim ’87 and wrote a business plan for a vineyard “in the hills where the cows didn’t want to go.”

“We knew nothing about vines, but we had land and Chilean know-how — and a soil engineer who pronounced the land ‘un wow lugar,’” Courtney says.

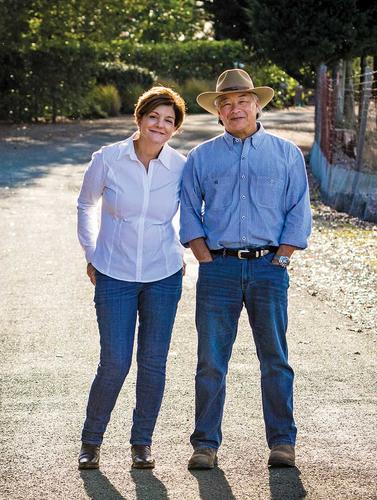

After much research and some inquiries with California wine powerhouses interested in expanding into Chile, the family used savings to plant the first vineyard. Courtney led sales and marketing and signed on as CEO, with her brother Tim ’87 advising as a founding partner. Their father, who had worked for Citibank and lives in Princeton, stepped in as CFO. Tim’s wife, Jennifer Pickens Kingston ’87, is COO. Michael’s sister Sally and her husband, Enrique Alliende, oversee day-to-day operations in Chile.

Some of the world’s oldest vines grow in Chile, because the country escaped the phylloxera epidemic of the 1800s. Cabernet sauvignon and carménère have been its signature red grapes, but the Kingstons gambled on pinot noir and syrah, sensing that the hilly Casablanca Valley would welcome cool-climate reds. They invested in vines, a winery, and a tasting room. They did not invest in salaries (“My husband is in tech, thank God,’” says Courtney), office space (“The North American HQ is in my house”), or unnecessarily expensive equipment (“We MacGyver everything”).

They partnered with a winemaker from a Napa winery esteemed for its pinot noir; he took a look at the Casablanca Valley and said it reminded him of Santa Barbara County with higher mountains. As it turned out, the soil was almost pure decomposed granite and, together with the intense afternoon sun, gave the red grapes great color.

In 2003, the Kingston Family label produced 450 cases. The winery now makes about 3,500 cases a year, crushing 10 percent of the grapes they grow and selling the rest. Meanwhile, Chile has become the seventh-largest producer of wines in the world.

Courtney has become an adherent of the “evergreen business” way, in which a company remains privately owned, focuses on long-term outcomes, and avoids raising capital that puts money before mission. She calls it “organic growth”: Move forward steadily with your employees and partners; value generations of the community as much as generations of the family. She created the winery’s education program; the Stanford Business School has written cases on the winery’s story. Students “read the Stanford cases and then come visit us as a class,” Courtney explains.

The education program saved the winery in 2020. Before the pandemic, about 20 percent of the winery’s 5,000 guests each year were students visiting through the education program. The rest were mostly adventurer travelers visiting the glaciers or the desert and hitting the winery as an aside. “They’d visit our winery and become lifelong customers,” says Courtney. But the winery shut down the same week that California did. Chile declared a state of catastrophe and its borders were closed.

The hospitality-driven marketing was gone. Then something happened. “Professors and MBAs familiar with our story asked if we could host their class discussion of the Kingston/Stanford case via Zoom,” she says in a phone conversation this spring. “We ship wines directly to the MBAs’ homes, and we all raise a glass together.” Recent additions include wine tastings for tech companies and what she calls “Uncle Ernie’s 80th-birthday celebration.”

“With each virtual class, with each bottle we taste,” she says, “we send money back to Chile to pay for our team.” The education program, she says, “brings my whole self, and our whole family, full circle.”

FOR LARRY ’79 AND MARYANN TSAI, founding a family winery was not about carrying on or creating a legacy. They’d each had successful corporate careers and were ready for a joint “second act.”

Tsai, a first-generation Chinese American, grew up on Long Island and majored in economics at Princeton. He harbored dreams of adventure but ended up entering Stanford Business School.

In 1984, while working in brand management at Carnation (now Nestlé), he met MaryAnn Nicastro, who worked in sales. She had grown up in a Boston Italian family and spent summers helping her grandmother tend a garden with vegetables, herbs, and her grandfather’s precious vineyard.

Several years, a few moves, and another MBA (hers) later, they were back in California, where MaryAnn worked at Beringer in Napa and Larry climbed the ladder in marketing and sales at food-industry companies large and small. When MaryAnn’s mentor, Mike Moone, left Beringer to start a new label, he hired MaryAnn as CEO, making her one of the first women in such a role in Napa Valley.

In 2003, with a nest egg they’d saved and her mentor as a partner, the couple started Moone-Tsai Vineyards. Taking advantage of their marketing muscle and their relationships in Napa Valley, they bought great grapes from great growers (sometimes ordering from exact rows on particular hillsides) and enlisted a Bordeaux-bred winemaker. Their wine is actually made at Brasswood, a Napa winery that makes its equipment available to custom-crush clients. The first vintage yielded 181 cases of wine that they “mostly drank and gave away,” says Larry. After a second vintage of 200 cases, the business was off and running. By 2008, they were producing 3,000 cases, and by 2012, they were both working full time for their company.

They run the business from a Spanish-style manse on Howell Mountain with a stunning view of Napa Valley. The Glass Fire came within one mile of the house, but at a table in a living room filled with Chinese art and antiques, Larry still pours the Paige Cuvee, a chardonnay named for his older daughter. He calls it a “prom princess” of a wine — golden in color and with notes of white flower, honey, and lemon candy. It is in an elegant Burgundian style, the oak and butter kept in check. He adds, “It’s the only Napa wine you’ll find in the cellar at 10 Downing Street.”

For Tsai, as for Princeton’s other alumni winery owners, the pandemic required new marketing strategies. The team at Moone-Tsai got aggressive with digital marketing, using the internet, email lists, social media, and partnerships to reach out directly to “the ultra-premium-quality wine folks” and offering bundling, special shipping, and other incentives. Moone-Tsai’s digital business went up “times five,” Tsai says, as more people bought more wine than before, drank it, and ordered again.

By the spring, Tsai seemed optimistic. He sensed pent-up demand for wine-country visits, which offer not just the chance to try and buy wine, but to drive through a beautiful landscape, meet people who care about wine, and share stories. “We deliver a multisensory experience,” he says.

Tsai turns philosophical when the talk turns to the particular resilience of a place like Napa Valley. “It’s not just dirt,” he muses about the idea of terroir. “When we talk about different soils, we’re comparing rocky volcanic soils with clay sediments and alluvial deposits in the valley’s former riverbeds. And we’re talking about old, gnarled vines growing in those difficult soils. Wines are best when they struggle.”

Constance Hale ’79 is a California journalist and author.

This story has been updated with clarifications in the section about Kingston Family Vineyards.

3 Responses

Peter Schroeder ’62

4 Years AgoAnother Princeton Family Winery

Your “All in the Family” article about wineries owned by Princeton families (June issue) overlooked Sonoma-based Petris Vineyard & Winery, which I have owned and run for more than a decade. We are proud of our many gold and silver medals over the years but more so from the accolades by my classmates when I supplied our award-winning Syrah wine for the Class of 1962 dinner at our 55th reunion.

Despite my MBA from Stanford and years as an international executive, I have been unable to control the vicissitudes of nature, which include too much or too little rain, heat, and sunshine. Like all Northern California wineries, we have suffered from wildfires that have engulfed our region in recent years. Although vineyards themselves rarely burn, smoke taint makes the harvest undrinkable, as happened to us in 2017 and again in 2020.

Growing up, I said I never wanted to be a farmer because I would constantly worry about the weather. But I am, and I do. However, like all farmers, optimism reigns supreme. We hope this year’s crop will escape the ravages of fire, extreme weather, and disease to give us the best vintage ever.

Paul Hertelendy ’53 (occasional deliver jockey for Hertelendy Vineyards)

4 Years AgoPrecarious Ventures

Kudos for your story on Princeton families in the wine business (June issue of PAW). People don’t realize what a precarious hand-to-mouth business it is for so many, with years of red balance sheets despite prize-winning wines. A pre-World-War family winery on Lake Balaton, Hungary, was the inspiration to start a one-man-band Napa Valley operation in 2013 for son Ralph, who happily has had a nose and palate miles beyond any of us, maybe like bloodhounds.

But a precarious venture? As he was swamped, I delivered for him a load of wines to enter a competition two hours’ drive away, with my smartphone leading me astray, arriving at the right door a scant five minutes before the final submission close. He got two prizes out of it from Sunset Magazine — two golds. Five minutes later, I’d have been mud. So it goes.

Cordially,

Arnie Breitbart ’81

4 Years AgoLabor of Love

I very much enjoyed your story on alumni wineries (“All In The Family,” June issue). To your list of esteemed alumni vineyards/wineries, I’d like to make a modest addition — mine, Chateau Marcelle (my daughter is Marcelle). Although it doesn’t have extensive acreage in Napa or Chile (just a small plot in my Long Island backyard), it’s not a livelihood-dependent commercial winery (just a very time-consuming hobby), and it doesn’t produce thousands of cases (just about 50 bottles in a good year, made in my basement, most of which I give away to family and friends), it is a labor of love. I plant and prune each vine, crush each grape, ferment each batch, and bottle/cork/label each bottle. And, as a self-professed Bruce Springsteen fanatic, over the years I have produced over 30 different wines commemorating over 30 different Springsteen albums.

I’ve also made wines to commemorate such things as my children’s weddings and our 35th Princeton reunion (above).