Architecture: Restoring Jewish History

A new exhibit re-examines the work of French designer Pierre Chareau

Recently, an innovative but little-known designer of 1920s and ’30s Paris found new renown in New York City. His name was Pierre Chareau, and he is the subject of an exhibit at the Jewish Museum in Manhattan.

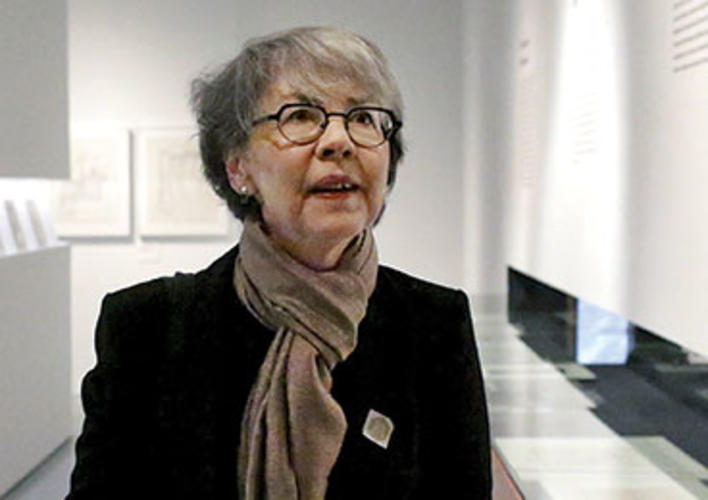

“Pierre Chareau: Modern Architecture and Design,” was curated by Esther da Costa Meyer, a professor of modern and contemporary architecture in the Department of Art and Archaeology who focuses on French architecture and urbanism from the mid-19th century to the present. In the show, she shares new discoveries about Chareau’s Jewish identity, which strongly affected his life.Chareau was born in 1883 and enjoyed great success through the 1920s and part of the ’30s designing furniture and interiors for wealthy clients and for the state. He was known for his luxurious modernist sensibility, often featuring juxtapositions of fine versus rough, such as alabaster or exotic woods with rough wrought-iron fittings. His most famous design is the iconic Maison de Verre, or House of Glass, in Paris — a steel, iron, and glass house designed in collaboration with Dutch architect Bernard Bijvoet. The exhibit features a virtual-reality re-creation of the house — one of several interactive displays created by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, co-founded by architecture professor Elizabeth Diller — which da Costa Meyer calls “absolutely exceptional.”

WATCH the virtual-reality display of the apartment, courtesy of the Jewish Museum

Over the past several years, da Costa Meyer has worked with Marquand Library and the Manuscripts Division to acquire documents, letters, and portfolios from the 1920s pertaining to Chareau, some of which are in the exhibit. She established Chareau’s Jewish ancestry through correspondence from his wife, Louise “Dollie” Dyte, recently acquired by Firestone’s Department of Rare Books and Special Collections. “We were able to show that it was this that prompted his flight from France during German occupation,” she said.

Chareau was raised Catholic, but his wife was Jewish, most of his clients were Jewish, and ultimately, he fled to Morocco, then the United States, several weeks after the German army marched into Paris. Many of his works were seized from their Jewish owners by the Nazis, and the work of locating and identifying them continues to this day.

In New York, Chareau couldn’t rebuild his old success, and he died in relative obscurity in 1950. “Each of Chareau’s pieces is a mute witness to a rarefied cultural milieu as well as to its violent destruction,” writes da Costa Meyer in the exhibit catalog. “The diaspora of objects and the circuitous routes by which they have found their way to new owners, museums, or high-end showrooms traces the afterlife of cultural artifacts and the sometimes tragic events that become the indelible inlay of their history.”

The exhibit had a personal impact on one Princetonian. New York Times journalist James Barron ’77 surprised his wife, Jane Farhi, with a visit to the show, which featured a virtual-reality re-creation of her grandparents’ apartment in Paris. They spent Christmas Day touring the exhibit on what da Costa Meyer calls “a magical and memorable morning.”

No responses yet