From the Archives: Princeton's 1975 NIT title

March 23 marks the 35th anniversary of one of Princeton's brightest basketball moments — the men's team's victory over Providence in the championship game of the 1975 National Invitation Tournament at Madison Square Garden.

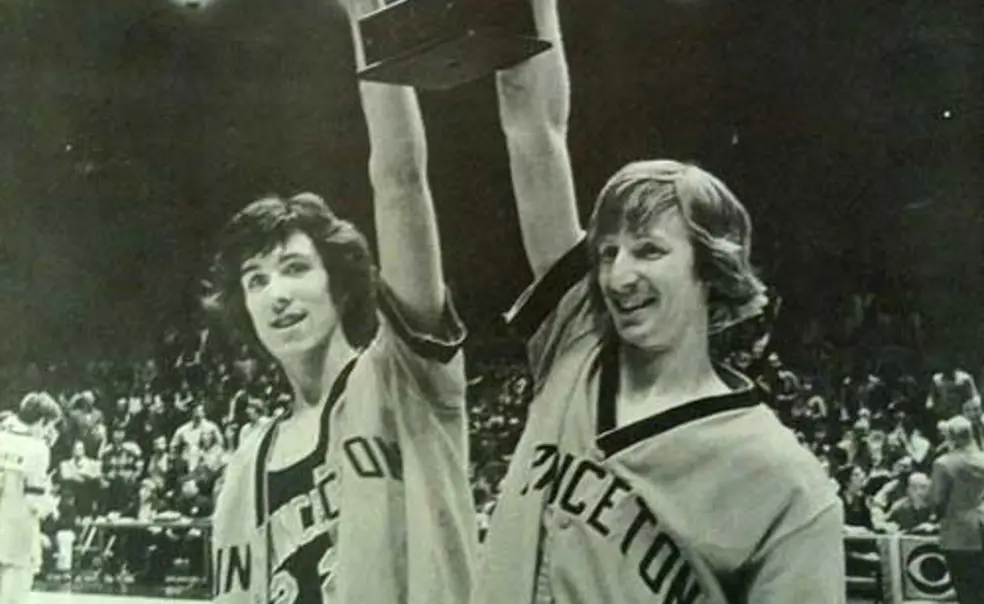

Led by captains Armond Hill ’85 and Mickey Steuerer ’76, Princeton went 18-8 in the regular season and won its last nine games, but Penn won the Ivy League, earning a spot to the NCAA Tournament. The Tigers accepted an NIT bid, and while the Quakers made a first-round exit in the NCAAs, coach Pete Carril's team continued its winning streak, building a following with each successive trip to New York. The championship run was a crowning achievement for Tim van Blommesteyn ’75, left, and Brien O'Neill ’75, who appeared on PAW's April 15, 1975, cover. Below, read Dan White ’65's account of Princeton's improbable postseason.

From PAW, April 15, 1975

'The Smart Shall Take from the Strong'

Princeton wins the National Invitation Tournament

By Dan White ’65

It was the most unlikely finish of the past decade. Originally picked to win less than half of its games, Princeton's basketball team went undefeated against its last 13 opponents and captured the National Invitation Tournament championship. In becoming the first Ivy school ever to win a post-season tourney, it triumphed over Holy Cross, South Carolina, Oregon, and Providence. Princeton's winning streak, currently the longest of any major college, propelled it to 12th place in the national rankings of the Associated Press.

Yet what will be remembered about this season is not so much a single victory (like the upset of South Carolina), or brilliant play (Tim van Blommesteyn racing downcourt with a stolen ball), or frustrating loss (Brown edging Princeton out of the Ivy lead), as the euphoria that caught up everyone, university and town alike, in the end.

More than 2,000 followers attended Princeton's first tournament game in New York's Madison Square Garden. As the team advanced from one stage to the next, others who had resisted at first joined in the madness. The trains to and from the city were choked with students and townspeople, ebulliently disputing the impossibility of it all. The Princeton crew chartered a bus for the Providence finale, and the baseball squad, bound for Florida, spent the eve of its departure at the South Carolina game. Sociology professor Marvin Bressler bolted a conference to catch the last few minutes of the Oregon match. Andy's Tavern on Alexander Road in Princeton -- owned by the avuncular Joe Fasanella, a close friend of head coach Pete Carril -- contributed a busload of its clientele to the crowd at the Garden.

When it was over, both the former New Jersey Governor, William Cahill, and the incumbent, Brendan Byrne ’49, telephoned their congratulations. President Bowen invited the team to his home. A record company proposed to make 5,000 plastic discs of the tournament highlights to sell to alumni. A pharmacy on Nassau Street placed a picture of Carril smiling and a stuffed tiger wearing sunglasses with tiger rims in its display window, next to bottles of Shalimar Talc and Parfums by Rochas. John Gorman ’39, a vice president of American Brands, sent the cigar-loving coach a box of La Coronas. The New York Times ran an editorial, titled "Tiger Burning Bright," praising Princeton's style of basketball, and the Philadelphia Inquirer gave the outcome a front-page banner headline.

The rule in modern basketball is that a team must have giants to win. Carril says his father, a steelworker who emigrated from Spain, once told him that the strong shall take from the weak, but the smart shall take from the strong. Man for man, the Princeton squad averaged 23 pounds less than Oregon, one of the most physical clubs in the country, but Carril prevailed by stressing smart defense, patience, discipline, and character. In the middle of the tournament, the television announcers, newspaper reporters, opposing coaches, and players began buzzing about an exciting new concept -- intelligence -- as if that were an exclusive Ivy League trait. After the final game, van Blommesteyn set the record straight: "It is the coach who instills intelligence in a team."

When a man coaches for 17 years, he sees all kinds of teams. Last December, Carril thought this would be his first really bad season at Princeton. Andy Rimol and Joe Vavricka had graduated, and no likely replacements appeared from the freshman squad. In early practices, his aspiring athletes dropped balls and muffed shots. Their seeming lack of intensity was particularly upsetting to Carril because his style is predicated on doing things right every single day. That should be a player's religion, says Carril. "Then he doesn't have to worry about where he plays, or whom he plays, or about rankings, and so on. It takes the emotion out of it, yet it is an emotional technique in itself. When the gimmicks and the slogans break down, he still has to play the game. He still has his daily behavior and patterns to fall back on. His modus operandi" -- a favorite phrase in the Carril lexicon -- "comes out."

After three weeks of practice, Carril decided to move van Blommesteyn from guard to forward to take advantage of his speed. The idea was to have the 6'3" senior concentrate on harassing opposing guards as they brought the ball up the court. If he could make his man pick up his dribble far enough away from the basket, he could disrupt the other team's offensive patterns. As it turned out, he would also manage to steal the ball 72 times during the season by blocking his opponent's path with his body, without touching him, and swiping at the ball with his hands. Employing the same technique, his teammates Mickey Steuerer and Armond Hill were to add 62 and 63 more thefts, respectively. All this larceny translated into hundreds of points, counting those denied to the opposition.

At Choate, van Blommesteyn played both basketball and soccer. He was not recruited by Carril, nor did he know who the coach was, but he had heard of Bill Bradley. Basketball was his favorite sport, what he thought he did best, so when he arrived at Princeton, he tried out for the freshman team. Carril watched him and suggested that he switch to soccer. Instead, van Blommesteyn led the 1971-72 freshmen in scoring with a 16.1 mark. As a sophomore guard, he averaged 20 minutes a game, constantly racing around the court on the verge of losing control. Although his speed and quick hands led to some early success, his aggressiveness also cost unnecessary fouls that soon had him at odds with Carril. Basketball soured in his junior year. He lost his starting position to Steuerer. When he did play, he shot poorly -- 20 percent -- and the word spread that he couldn't shoot. His confidence waned.

So did his relations with his coach. To van Blommesteyn, Carril was too intense, too demanding. On the other hand, van Blommesteyn seemed a basketball dilettante, lacking in dedication to self-improvement. After he threw the ball away in practice one day, Carril told him he had to be blind to make a pass like that. Van Blommesteyn retorted, "Okay, I am blind," and Carril blew up. He resumed drilling van Blommesteyn over and over until the lessons began to take. Finally, on the strength of a good showing against Penn, van Blommesteyn moved back into Carril's scheme of things for good.

Following the switch of positions, van Blommesteyn twice scored a career high of 26 points, against Penn and Cornell, and chased opposing ball-handlers with lupine cunning. "I never thought before this year," he later reflected, "that intensity was important. Basketball had to be fun for me: If it hadn't been, I would have dropped it. Last year, I wasn't performing up to my ability. That got Carril angry more than anything. In the end, I learned things that transcend basketball. Carril was right."

Meanwhile, the team was learning that it could win with defense. Six of the first nine opponents scored fewer than 66 points; Penn managed only 49. But problems remained in shooting and rebounding. In its four early season defeats, Princeton's highest point total was 67, and against South Carolina it dipped to 48. As a consolation the players received wristwatches at the Carolina Classic. At the start of the new year, Princeton lost its return match with Penn, which locked the two teams in a tie for first place in the Ivy League. Then, up at Providence, Brown pulled out a 62-61 victory that relegated Princeton to its third successive finish behind Penn. "It was rough for the guys; it looked like I would be second-place-Pete again," says Carril. "From then on, we had to salvage the season." Princeton played only one more bad game, against Yale, and finished 18-8 with a nine-game winning streak. For the eighth time in 10 years, Princeton was ranked among the nation's 10 best teams defensively, rated third this year for its paltry dole of 61.2 points per adversary.

"Eighteen wins has to be a success story," noted Carril at the end of the regular season. It was a success story without a star performer. The 10-man squad had seven guards and no game-breaker, no single superathlete around which to mold the team's skills and character as had been done with Bill Bradley ’65, Geoff Petrie ’70, and Brian Taylor ’73. The top scorer was Barnes Hauptfuhrer with a 14.7 average. The 6'7" junior had a proclivity for jump shots from the corners in the tradition of the Haarlow brothers of the 1960s. Against Notre Dame, he established a Princeton record for marksmanship, making 11 field goals in 11 attempts. Graceful and long-armed, he was equally proficient on defense, limiting his man in 10 games to fewer than 10 points. He was recruited by Carril, who saw him play three times at Penn Charter School in Philadelphia. "He had a nice handshake," says Carril. "Barnes is 80 percent tension, 20 percent talent. There are times when I could hit him with a sledgehammer, but he has great work habits."

Although Princeton was the first college chosen by the Selection Committee for the 38th National Invitation Tournament, no one expected the team to go very far against the other high-ranked participants. Princeton had been to the NIT once before, in 1972, but was eliminated in the quarterfinals. The players, of course, were excited just to be playing at the Garden, which is still the Mecca of eastern basketball. Carril and his assistant, Gary Walters ’67, were mainly concerned about not being embarrassed in the tournament. Their plan was to stick with their proven style, work hard, and hope to hang in there. Carril's attitude was characteristically pessimistic. Walters, who played for Carril in high school and was coached at Princeton by Butch van Breda Kolff ’45 (Carril's mentor in 1952 at Lafayette), even made personal plans to travel to Schenectady, New York, the weekend the tourney would be winding up.

Similarly, Steuerer planned to join friends in Florida over spring vacation, assuming Princeton was eliminated early in the tournament. At the same time. Mark Hartley, a sophomore forward who had endured the long adventure with small knots of torn muscle in his ankles, was worried about how the games might affect course papers he had to write. During the few days' lull before the NIT draws were completed, van Blommesteyn was busy with the atomic adsorption spectrophotometer in the geology lab, analyzing samples he had been collecting for a month from Princeton's water system. As a senior project, he was undertaking the first water quality study at the university. Already he had discovered concentrations of copper, sodium, and magnesium in water taken from Guyot Hall that were higher than elsewhere on campus.

For the opening round of the NIT Princeton drew Holy Cross, a team that had reversed an 8-18 swoon last season to compile a 20-7 record this year under George Blaney, a one-time Dartmouth coach and one of three ex-Ivy coaches Princeton would face in the tournament. Some myopic writers were calling it the Cinderella team of the Northeast. Its strength was a patient offense and a full court press. Breaking open that press would be the key to beating Holy Cross.

A full-court press is probably the most fatiguing maneuver a coach can employ. To avoid being trapped by the defense, every opposing player must constantly move about and strain for a break. After a basket, a team has five seconds to inbound the ball or else it forfeits possession. Holy Cross could be expected to station one of its players directly in front of the man inbounding the ball and have him wave his arms in his face to obstruct his view. With the seconds ticking by, the Princeton guard might hurry the pass. The risks of misjudgement and interception would be high. If he tossed the ball to a teammate close by, then Holy Cross would jump him with two men and try to fence him in along the sideline. An effective press could cause panic and disrupt Princeton's deliberate offense.

Carril decided on an unorthodox strategy. Steuerer would take the ball out of bounds on one side of the court, pulling the defender with him. Hill would position himself on the other side of the floor, then step quickly out of bounds, receive a pass from Steuerer, and look for an open man. Carril thought the point man on Steuerer would then have to choose between two options -- stay with Steuerer or resume coverage of the out-of-bounds passer. If he switched, Steurer would run onto the court and take the pass. If the point man stayed, then Hill would look for van Blommesteyn coming back into an open lane. The strength of the press is also its weakness. If van Blommesteyn could get beyond the initial defenders, Princeton would outnumber the remaining men.

Before a Sunday afternoon crowd of 11,600, Hill, Steuerer, and van Blommesteyn employed these tactics perfectly and executed a dozen lay-ups. Holy Cross, forced to take long-range shots and to shoot off-balance, couldn't approach its average of 80 points a game. Midway through the second half, it collapsed from exhaustion and frustration. With two minutes left, Princeton led by 24. Walters turned to Carril and said, "Congratulations, Coach." Carril shot back, "What do you mean, it's not over yet." The final score was 84-63. Hauptfuhrer accounted for 19 points and grabbed eight rebounds. Steuerer contributed six assists. Of possibly greater significance, in place of Ilan Ramati and Hill, who sat out much of the game with four fouls apiece, Carril had sent in Hartley and senior Brien O'Neill. Running on pins and needles, Hartley scored 16 points, more than triple his season average. O'Neill supplied 12 points on leaping lay-ups. "We are still alive," Carril told the media. "We now have the ignominious pleasure of playing South Carolina."

In its opener, South Carolina had beaten Connecticut, 71-61, without undue strain, it was noted. After all, this was a team that had survived the caldron of Atlantic Coast competition, trounced Princeton in December, lost twice to seventh-ranked Marquette by a total of only 12 points, and extended Notre Dame to overtime. For five consecutive years, coach Frank McGuire had taken South Carolina to post-season tournaments. As Walters put it, "They had no visible weaknesses."

Carril's hope was to make South Carolina change from its favorite defense, a zone, to a man-to-man against which Princeton's movement, passing, and quick cuts could be more effective. He disliked the prospect of playing against a zone for two reasons: He had only one consistent jump shooter, Hauptfuhrer, and he did not have a guard who could make a snappy chest pass -- the kind Carril felt he needed to counteract the shifting of a zone. In December, McGuire had zoned Princeton. Hill was on the bench in foul trouble, and the rest of the team was really struggling to make a game of it. But in the final half, South Carolina suddenly changed to a man-to-man and ran away from Princeton. Perhaps McGuire would attribute his success to that tactic and try it again.

South Carolina's front line of superluminaries had produced 50 points a game in the season. Its 6'9" center, Tom Boswell, would compete against Ramati, the 6'8" sophomore who had moved up when Jim Flores broke his jaw in the Harvard game. Alex English, a 6'8" forward, would be defended by Hauptfuhrer. Carolina freshman Jack Gilloon, the most heavily recruited high school player in the Northeast, styled himself after Pete Maravich. He could thread a needle with a pass to an open man. Van Blommesteyn would take him.

Hill signaled the start with a turn-around jump shot and Princeton rushed to a 21-10 margin. Momentarily, South Carolina seemed more intent upon trying to draw fouls than on playing basketball. At the slightest contact, the Southerners fell to the floor, but the referees ignored them. Wherever Gilloon went, van Blommesteyn went, belly-to-belly. Gilloon began to heave long one-handers that became flicks of orange in the Garden stratosphere before they dropped, way off-target, into the arms of Hill, Hauptfuhrer, and Ramati. Jimmy Walsh, the other Carolina guard, committed four errors in the beginning four minutes and disappeared from action. Boswell and English came out to get the ball, then tried to muscle it in to close range of the basket, but the referees penalized them for charging. They cast quizzical looks toward McGuire and retreated.

Dribbling upcourt with seven minutes elapsed, Hill realized that South Carolina had taken off its zone for the man-to-man. Steuerer saw the switch too and edged to the side. He planted his foot, whirled around the defender, and ran for the basket, calling "Armond!" Hill, without looking, bounced the ball to Steuerer, who pushed it up for two points. It was the classic "coup" in Carril's offense, what he refers to as "going back door." Princeton would repeat it a dozen more times that evening, catching the bigger, but slower, Carolina players off-balance and over extended. "Moving the ball around -- there has to be an understanding of what you have to do," says Carril. "Movement, finesse, passing, these are things that don't seem prevalent any more -- it's all muscle."

By the end of the half, the crowd of 11,425 -- the majority of whom favored South Carolina's New York-born athletes -- had witnessed the complete disintegration of a team. High above the arena, smoke-filled like a huge fumarole, the Garden scoreboard showed: Princeton 42, South Carolina 24. Hill had played the best single half of his career, scoring 18 points, contributing two assists, and stealing the ball twice. The Carolina defensive specialist assigned to him, Mark Greiner, gave up the ghost 10 minutes into the game and left the floor. Four more stalwarts took turns trying to stop Hill from penetrating the middle of the Carolina team. They resorted to grabbing his shirt.

At the opening of the second half, Princeton rattled off three lay-ups to abort a South Carolina comeback. In the final minutes, the assemblage of Princeton zealots chanted "Armond, Armond" and shouted, "We own you Carolina, we own you." As the horn sounded, the scoreboard blinked to 80-67. Because Holy Cross had a reputation as a Cinderella team, the true significance of Princeton's first victory had been suspect, but South Carolina was different. And Princeton had given it a sound beating, holding its highest scorer to eight points, its two big men to 17. From this game, Princeton's confidence, a little thing before, would rise unchecked.

Van Blommesteyn had tallied 24 points; sore-ankled Hartley had played 15 minutes and contributed 12 more; Ramati had led all rebounders with eight. But the star was Hill . . . everyone was talking about Hill. "It was a great thing for the kid," says Carril, "after the tragedy he went through last year, it was a great thing." Hill played 20 games in 1974 before academic problems required him to withdraw from school. His pride smarting, he had doubts about returning to Princeton. For six months he did not touch a basketball. To pay off some loans, he found a construction job and worked part-time in a radio station. He finally decided to come back, he said, because he wanted to prove himself.

During the regular season, Hill scored 14.6 points a game and was unanimously chosen all-league. Princeton's best defender against the jump shot, he always seemed able to get his hand in the shooter's face. "When he was a senior at Bishop Ford High School in Brooklyn, I took one look at the kid and felt that pulse in my heart," recalls Carril. "There is no tangible evidence to explain the feeling, but I knew he was going to be great." Though Hill is some times accused of not being consistently aggressive, he is also reputed to have played against professional star Geoff Petrie ’70 in individual competition and to have been told afterwards, "Armond, the only difference between you and me is that I'm stronger." In Carril's view, "He has all the mechanical skills to become a good player in the pros, but he needs to work hard to improve his stamina."

During its first two tournament games, Princeton had controlled the tempo from the outset. The idea of an early lead was fundamental to Carril's strategy because his team lacked the size and height to capture its share of garbage-points which come from misguided shots tipped in by taller players and which are necessary in order to come from behind. "We have to bleed for points," agrees Walters. "We work hard for every point we get."

Looking out on the floor at Oregon, Walters decided Princeton had the skinniest team in the tournament, if not in the country. By comparison, Oregon had the best rebounders in the tough Pacific Eight Conference. And its coach, Dick Harter, was one of the best defensive minds in the business. During five years at Penn he had played against Carril's teams many times. He knew about the back door, and he had drilled many of Carril's tactics into his own squad. Its record was 18-8, but six of those losses were by a total of nine points.

Oregon's line-up centered around its all-American guard, Ron Lee -- a marvelous athlete, sleek at 6'4", strong at 195 pounds, and so full of nervous energy that he requires only three or four hours of sleep a night. During the regular season, he had compiled 938 minutes of playing time, 137 more than any of his teammates, while averaging 17.3 points, 5.3 assists, and 5.4 rebounds. In planning for the game, Carril decided he did not want Hill to defend against Lee. That would get Hill in foul trouble because Lee was expert at taking his man inside and forcing physical contact. On the other hand, Lee was a gelid outside shooter, 38 percent for the season. The player who was best at fronting people inside was Steuerer. He would take Lee.

Steuerer felt quite at home in the Garden, having played many games there for Archbishop High School in Richmond Hill, New York. Not a physically imposing athlete, he was another in a long line of excellent Princeton guards. He always seemed to know what to do. First in assists, third-highest scorer, fourth rebounder, gilt-edged as a ballhandler, he had played 35 minutes a game during the regular season and made less than one turnover per outing. He held Notre Dame's super-mogul Adrian Dantley to 20 points when he was averaging 40, Phil Sellers of Rutgers to 12, and Steve Switchenko to six after the Yalie had scored 45 in his two previous efforts. In 14 games, the man Steuerer defended scored less than 10 points. Another set of statistics shows him winning a jump ball 14 of 15 times, drawing an average of two fouls from his opponents, recovering at least three loose balls each contest, and, in seven of 18 victories, scoring what were deemed essential points. Carril liked to call him his most valuable player, his assistant coach on the floor.

Carril had predicted that Oregon would be his most difficult game, but he was relaxed. He told a television announcer who was after him for an interview that if Princeton won the NIT, he'd do the interview standing on his head (and he did). He permitted Hartley to remain in Princeton the day before to complete his papers. The rest of the team took the train to New York and spent the night in a hotel. Saturday afternoon the effects of tournament fatigue and of a fitful night in hotel beds built too short for basketball players showed on the floor for the first time. Oregon anticipated every attempt by Princeton at a backdoor play. Hill forced his shots, missed badly, and then stopped shooting altogether. Crossing up Carril, Lee took Steuerer into the corners where he released the ball at what seemed to be impossible angles and scored frequently to keep Oregon hotly in contention. Van Blommesteyn had 10 points, yet it was Ramati who kept Princeton out in front, though never decisively, in the first half. He chipped in shots four and five feet from the basket, then ran down court to box out the opposing forwards for the rebounds. Princeton opened a gap of six points, but just before the intermission, Oregon narrowed it to two. This time Princeton was going to have to go down to the wire.

In the first 10 minutes of the second half, Princeton committed three mistakes in a row and Oregon laid on six points to go ahead by four. Then Steuerer got Lee crosslegged and drove around him for a lay-up, van Blommesteyn swiped the ball for two more points, and the defense stiffened. In the remaining seven minutes, Princeton would allow the opposition just one field goal. Hill sank a short jumper to take the lead, 56-55, and Oregon regained it for the last time. Hill came downcourt bouncing the ball high. He passed to Steuerer, who threw to Hauptfuhrer. Back it came, around the circle, back and forth, the way basketball was played 20 years ago. Princeton would hold for one shot. Hill saw it, took it, and missed but was fouled. He made both points and Princeton went ahead, 58-57. At this point, Carril told Hill to change with Steuerer and cover Lee. He wanted his best defender against the jump shot on him. Oregon passed the ball for 45 seconds. Then Peter Molloy, in the game to lend some extra ball-handling prowess, intercepted a pass and Princeton returned to its freeze. With 13 seconds left, Oregon, its options gone, fouled Ramati. He had one shot and a bonus if he made the first. A double conversion would guarantee victory.

Ramati thought about what Carril had been telling him all year. He had to concentrate more on his follow-through when he shot. He bounced the ball at the foul line. This time he would heed Carril's instructions to the letter. He drew back his arm, cocked his wrist, and released the ball. The form was flawless, but the ball fell under the basket. Oregon grabbed it and called time out to set up its final play. Lee got the inbounds pass and started to drive, but Molloy darted in front of him. Lee stopped, circled back, and, with time elapsed, had to throw up the shot. Hill had his hand on it, and the ball fell far short as the buzzer sounded.

Carril flung his coat into the air and flashed victory signs to his friends. He told reporters, "My happiness today belongs to Ramati. He has improved so much and still has so much more to go. Maybe after today, he will believe in all the sacrifices I have asked him to make." In 37 minutes of play, Ramati had scored 13 points and, together with Hauptfuhrer, retrieved most of Princeton's 30 rebounds -- a total that exceeded Oregon's by six.

Carril recalled that when he first saw the scouting report from Riverside School in New York City, he didn't think Ramati could "rebound his way out of a test tube." In preseason discussion, Carril had told him he had to become more physical under the boards. Most of the season, he sat on the bench while Flores played. Ramati saw so little action in one game that he decided not to shower afterwards so he could leave early. (Walters stopped him and sent him into the showers.) He had a reputation for being unpredictable. His long legs seemed herky jerky. But In the first three games of the tournament, he had displayed a deft shooting touch, rebounded vigorously, and given Princeton crucial mobility in the front.

Ironically, Princeton felt Providence was the team it had the best chance of beating if it got to the championship round. There was the matter of precedent: Princeton had last played Providence in the NCAA Eastern Regional Championships in 1965, winning 109-69. That was Bradley's team, and it included a sophomore guard named Walters. This year, moreover, each Providence player had a trait that Princeton felt it could take advantage of. Forward Bruce Campbell didn't move well to his right. Joe Hassett, who had scored 24, 18, and 22 points already, seemed unsure going to his left. Since he would be the most important player to stop, Carril instructed Hill to overplay him to his strong side and deny him his favorite move to the right corner. "I told Hill that sometimes you can beat someone with your body, sometimes with your head. Against Hassett, he would have to do both." Van Blommesteyn was faster than the man he would cover, Gary Bello, a clever shooter who was eager to drive. On defense, Providence liked to break fast down the court; to check that, Princeton would have to retreat speedily.

With Steuerer controlling the pace and shooting well, Princeton went out in front by 11 points midway through the first half. Hill continued his epochal slump but riveted himself to Hassett's right arm. Van Blommesteyn was hot, and it looked for awhile like Princeton might make a rout of it. Then Providence started to run and Princeton indiscreetly began running too. Van Blommesteyn lost his breath, then his legs, and began to sag off Bello, who now found the middle pliable. In the closing minutes of the half, Providence outscored Princeton 13-4 to trail by only one point at the intermission, 38-37. Providence's coach, Dave Gavitt (whom Walters once served as freshman coach when he was at Dartmouth), had zoned Princeton with a two-three variation that enabled his players to cover Hauptfuhrer on the wing and apply pressure out front simultaneously.

In the locker room, Carril reminded his team that it must not try to run with Providence, and that it must retreat quickly on defense to stop the fast break. He would alternate Hill and Steuerer in the pivot in the second half to utilize their driving and passing ability against the center of the defense. To get the ball to them, Carril decided to substitute Molloy -- a crafty, dexterous ball-handler who always got back on defense -- for van Blommesteyn, who along with Steuerer had provided most of Princeton's scoring so far but was tiring. Van Blommesteyn went over to Molloy and said, "Just go in and play a great game."

When play resumed, Steuerer scored six points in a run of eight to send Princeton ahead, 46-39. Providence worked back to within three. With ten minutes remaining and Princeton leading 56-53, Carril put his aces on the table and went to a four-guard offense. Van Blommesteyn reentered the game and, in a four-minute span, scored seven of Princeton's next 10 points, pushing the lead to 66-57. He and his teammates passed back and forth to each other, freezing play and forcing Providence to chase the ball. From then on, Princeton walked away with it to win, 86-67. Molloy scored seven points, had four assists and three steals. Steuerer registered 26 points on nine of 12 field goals and eight foul conversions. Van Blommesteyn had 23; Ramati, 10. Hill was top rebounder, and Hauptfuhrer led in assists. At the buzzer, Carril threw a basketball high in the air, danced a jig, grabbed the Princeton tiger and danced another jig. The crowd spilled onto the floor. Van Blommesteyn and O'Neill hoisted the NIT trophy above their heads.

Someone got Carril to a television camera. He said, "We had no advantages. We have no scholarships, no freshman eligibility, and we can talk only to about 3 percent of the high school seniors who play basketball in this country. How do you figure it? I've just got a bunch of terrific kids. They've got brains and courage. How can you ever beat that? That's what life is all about. Anyone can teach them what I know about basketball, but they're ready for more important things. Don't wake me, let me dream."

Then Walters came by with his NIT watch fastened around his wrist. "The Carolina watch," he said, "broke a month ago."

No responses yet