Are Grades Too High?

Alumni views on decade-long policy sought as A’s soar across the country

As a faculty committee continues its review of the University’s grading policy, alumni and others in the Princeton community can weigh in on the issue in an online survey through the end of May.

The committee has surveyed students and faculty as part of its charge to review the effectiveness and “unintended impacts” of Princeton’s 10-year-old policy aimed at curbing grade inflation. The group also is gathering data on graduates’ success rates in graduate and professional schools, ROTC placement, and competitiveness for Rhodes and Marshall scholarships, said Clarence Rowley ’95, a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering and the committee’s chair.

Alumni feedback will help identify impacts of the policy on graduates’ career and educational opportunities, said Elizabeth Colagiuri, associate dean of the college. She said the committee is particularly interested in responses from alumni who were on campus after the guidelines were implemented and who can speak to how the policy affected their lives on both sides of FitzRandolph Gate. (The survey can be found at www.princeton.edu/gradingsurvey/.)

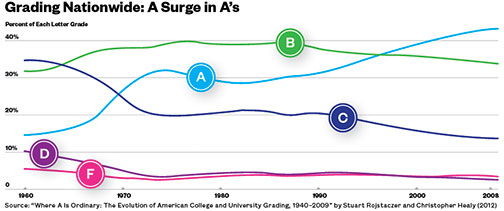

Grade inflation has long been a vexing problem across higher education. A study by Stuart Rojstaczer and Christopher Healy of grading data from 200 four-year colleges and universities from 1940 to 2009 found that A’s represent 43 percent of all letter grades on college campuses, up from 15 percent in 1960 and 31 percent in 1988. The total of D’s and F’s, meanwhile, has decreased to less than 10 percent.

Grades skew higher at private institutions than at public schools with equal student selectivity, the study showed, with A’s and B’s accounting for 86 percent of all grades at private schools, compared with 73 percent at public universities. The study also found that Southern colleges grade more harshly than schools in other regions, and that science and engineering schools tend to have lower GPAs than institutions that emphasize the liberal arts.

The authors attribute the steep rise in grades to a shift in academic culture toward treating students as consumers. Rojstaczer, a former Duke geophysics professor who maintains the site gradeinflation.com, said the trend has not been accompanied by increasing student achievement, noting findings that students today spend fewer hours studying than previous generations did.

Such top-heavy grading makes it difficult to communicate to students how well they’re performing and disadvantages top students by failing to reward truly outstanding work, said Richard Kamber, a philosophy professor at the College of New Jersey who has written about grade inflation.

At Harvard University, where the most commonly awarded grade is an A, Harvey Mansfield, a professor of government, gives students two grades: one he feels they deserve, and another that appears on their transcripts.

Grade inflation also can make grades less useful to others. When employers see A’s from institutions where A’s are common, said Sita Slavov, an economist at the American Enterprise Institute, “what can they say about you except that you’re average?”

Many take different grading scales in stride. Law schools, for example, often employ algorithms based on colleges’ grading histories to compare applicants. Ernst & Young uses the performance of past cohorts of hires to gauge institutions’ grading curves and how well prepared their graduates are, said Dan Black, the company’s director of recruiting for the Americas. Princeton students, he noted, benefit from the University’s reputation for academic excellence. “That is a fact that is not lost on any recruiter who knows his or her business,” he said.

Although Princeton is still shy of its target — limiting A’s to no more than 35 percent of undergraduate grades — the policy has reduced the percentage of A grades from 47 percent in 2001–04 to 41.8 percent in 2010–13. Few institutions, however, have followed suit.

In 2004, Wellesley College adopted guidelines setting the expectation that the mean grade for 100- and 200-level classes with more than 10 students should not exceed a 3.3 or B+. The guidelines “preserved the credibility of every Wellesley transcript,” said provost Andrew Shennan, by lowering the mean grade from 3.53 in 2001 to 3.34 in 2011 and reducing grading imbalances between the sciences and humanities. Shennan said the policy hasn’t appeared to hinder post-baccalaureate success, noting positive feedback from fellowship and grad-school selection committees, but student anxiety persists.

At Yale University, where 62 percent of the grades in 2012 were A’s, an ad hoc committee has proposed guidelines similar to Princeton’s, limiting the distribution of A’s in a class to 35 percent. Winning backing for the proposal likely will be considerably more difficult if Princeton reverses course, said Ray Fair, an economics professor who chaired Yale’s committee.

Though it’s too early to say whether the committee evaluating Princeton’s guidelines will recommend adjustments when it issues its report this summer, “we’re considering everything,” Rowley said.

“We want to do what’s best for our students,” he said. “If you give everybody A’s, there’s no incentive to actually study a subject and get immersed in it and learn to love it. But if you’re too strict and students feel they’re in competition or you’re penalizing them and making it more difficult for them to get into graduate school, you’re also not doing the best thing.”

2 Responses

Stephen C. Jett ’60

10 Years AgoGrades That Mean Something

“Are Grades Too High?” (On the Campus, April 23) took me back to a 1956 Keycept on the desirability of grading.

My opinions remain unchanged following a 37-year university-teaching career. Grade-free (or free-grade) learning can lead to laziness; meaningful grades provide a sport-like incentive and a standard for measuring one’s achievement.

Outstanding talents from grade-inflated institutions can’t be distinguished from their cohorts, and graduate schools and employers lack this means of identifying standout candidates.

Even Princeton grades become meaningless if mostly As and Bs. Grades should record relative, not absolute performance, with grad schools and hirers considering the comparative values of A’s from Princeton versus A’s from elsewhere.

Grade inflation began in the Vietnam era, supporting student draft-exemptions. Too, the self-esteem movement contributed, as did the consumerist view of education. Maintaining traditional grading standards ultimately became impossible as faculty inflaters overwhelmed us few foot-draggers.

Whereas the undergraduate population had been mostly middle-class and the grade-distribution curve bell-shaped, average performance later declined and the curve became bimodal. This bimodality reflected a contrast between students from affluent and educated English-speaking backgrounds that included recreational reading, and lower-income, first-generation higher-education participants, with limited parental education, minimal reading experience, and (among 30 percent at my campus) English not the household tongue. Many such students had to work to pay for their educations, leaving less time for academics. Another notable factor was the arrival of admittees who had grown up entirely in the television/Internet age, in which reading was minimal.

John W. Minton Jr. ’50

10 Years AgoGrades That Mean Something

Back when I was riding my dinosaur to class (1946–1950), we were graded from 1+ (the best) to 7- (see you next year). As an engineering student, I suppose it was easier to establish a grade (2+2 always equaled 4), but I knew lots of non-engineers whose grading didn’t seem to be a problem for their professors.

When Princeton changed from the education model to the business model and grade enhancement became a way of life, the grading process changed. I have always believed that grades should represent what you have learned and retained, not a way of improving Princeton’s standing in the rarified air of the “best schools.” One of my classmates topped the charts every semester with a 1+, and I am sure he earned it.

After one leaves the halls of higher learning for what used to be the real world, one hopefully will be judged based on performance, not a framed piece of parchment on the wall of one’s den or office. The study quoted bears out the business-model problem. Higher costs must equate to better results in academia.