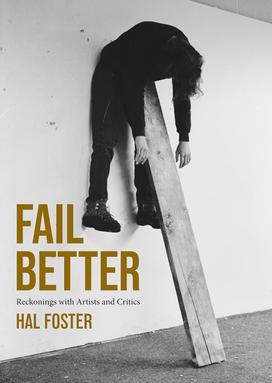

Art Professor Hal Foster Dives Into the Work of Critics

The book: Irish writer Samuel Beckett’s mantra “try again, fail again, fail better” comes from his 1983 story “Worstward Ho.” Foster uses this idea as inspiration for Fail Better (MIT Press) as he explores the world and work of critics. He traces the development of criticism since the early 1960s in this collection of 40 texts. Among those he analyses are Louis Lawler, Rhicard Hamilton, and Jasper Johns.

The author: Hal Foster is the Townsend Martin, Class of 1917, Professor of Art and Archaeology at Princeton University. He teaches and publishes in the areas of modernist and contemporary art, architecture, and theory. His interests include the relationship between art and philosophy at times of political crisis. Foster also teaches in the Department of German and sits on the executive committee of the Program in Media and Modernity.

Excerpt:

Most of the 40 essays collected in Fail Better: Reckonings with Artists and Critics were published over the last 20 years, but some recently, so why offer them up again? One reason is simple: I wanted another crack at them. Etymologically, an essay is a trial, and mine were affected by the contingencies of the occasion. Frequently, then, an essay calls out for another attempt, which I have made in most instances here. That’s one meaning of the (anti)motto I borrow from Samuel Beckett: “try again, fail again, fail better.”

I have also reached the point where I want to take stock. I turn 70 in 2025, and my first collection of essays, Recodings: Art, Spectacle, Cultural Politics, appeared forty years ago. Buoyed by new practices and theories of art, Recodings mainly looked ahead, whereas this book of reckonings mostly gazes back. Most of the artists I term “antecedents” aren’t alive, most of the “contemporaries” aren’t young, and the “critics” who are still with us are long in the tooth.

My roster is far from comprehensive (I am a situated writer, one long based in New York), nor is it inclusive, and many will object to its lack of diversity. Although several “contemporaries” are key feminists, and difference is a central concern in all three sections, nearly all the “antecedents” are white men. I can’t defend this limitation, which is another version of failure, apart from the fact that I present what I know best, I have published on artists of color elsewhere, and others do this crucial work better in any case (I see criticism as collaborative in this way). Clearly, I write from the center––mostly about known figures, in established publications, from a privileged university––but I do so in part because value is concentrated there and so might be revised there as well. At the same time the center isn’t so central anymore, and what was once assumed as knowledge about postwar practice can no longer be taken for granted.

The texts vary widely. Some are brief, others extensive. Some tend to the analytical, others to the synthetic. Some concentrate on a single body of work, others review entire careers. Some focus on beginnings, others on mid-career shifts, and a few touch on late styles. In this respect, too, they are not comprehensive, yet each essay does aim to articulate a salient concept of the practice in question. By the 1980s ambitious modernist art history was divided between semiotic and social-historical approaches. This was never an either-or for me: I have always focused not only on how an artwork signifies but also on what it says about the conditions that prompt it––on the historicity of the ideas embedded in the practice. For me that’s the best way to address what Roland Barthes called “the historical responsibility of forms,” to come to terms with the work and its moment in one go.

This needn’t be an obscure operation. Many of the texts first appeared in the London Review of Books, which has implications for readership: I have aimed to contribute to a shared understanding of postwar art and criticism in a way that doesn’t depend on inside information, and this is true of the essays written for Artforum as well. At the same time, though some of the texts are streamlined to suit the speediness of electronic publication, clarity needn’t be the enemy of complexity. In any case, this book contains little in the way of scholarly apparatus: it’s the work of a critic more than a contemporary art historian (a category that still seems a little oxymoronic to me). There are a couple of reasons for this positioning. First, I’m acquainted with a good number of the figures in the book. This is a mixed blessing, since status as a participant-observer also has its disadvantages; insight can come through proximity, but perspective can suffer as well. Second, many of these practices aren’t things of the past for me; many “antecedents” might be historical, but not most “contemporaries.” In part that’s why I have opted for the two rubrics, inadequate though they are. By “antecedent,” which combines “before” and “go” (ante + cedere), I simply mean an artist who emerged in a historical conjuncture prior to that of my generation. And I intend “contemporary” in the sense less of similar age than of shared history, of inhabiting a fractured time together (con + tempus). Crucially, too, the “antecedents” are among the artists who set the terms of artmaking for the “contemporaries.”

If many readers view most figures in this book as historical, the question becomes how to position them. Like other critics, I once relied on two concepts to periodize postwar art: postmodernism and the neo-avant-garde. Yet the model of a restrictive (medium-specific) modernism opened up by an expansive (post-medium) postmodernism no longer guides important developments, and the same is true of the schema of a prewar avant-garde recovered by a postwar neo-avant-garde. Although other frames not so based on Western European and North American practices have come to the fore––frames like diasporic connections, “archipelagic thought,” and global transfers––the old context isn’t devoid of paradigms and patterns either. For example, a partial genealogy can be traced through different stagings of the body, from its immediate presence in much art of the 1960s, through its performed abjection in some work of the 1990s, to its partial virtualization in recent video installations and digital simulations. A second line could be drawn through various conceptions of site over the last six decades—as a matter first of physical location, then of institutional setting, and finally of discursive spaces that artists explore almost in the manner of field research. And a third tale might be told through successive transformations of the image, from the crossing of painting and commodity in Pop art, through the appropriation of mass-cultural signs in postmodernism, to the extensive absorption of art in the media-market of the present . . .

I am in no position to historicize myself. Hardly an insightful reader of my own work, I advise students not to follow my own tentative lead but to look to the blind spots in the writing of predecessors that most interests them. That said, let me point to a few basic shifts that have occurred since my earlier volumes of essays. The first, obvious enough, is the change in the valence of appropriation––from a strategy in which images were purloined, from mass media, art history, and elsewhere, in order to question claims about property and originality, to a concern about cultural theft that often insists on representation precisely as original property. Another shift involves framings of the real. In the 1980s much art presented reality as a construction, a view that responded to a society shot through with media spectacle. First proposed in Pop art, this symbolic conception of the real was pervasive by the advent of postmodernism. However, with the slashing of welfare and the raging of AIDS in the 1990s, the real came to be positioned less as an effect of representation than as a site of trauma, and the damaged human body was often staged as a figure of a broken body politic. In recent years the terms have shift again: the mediation of the real is accepted as given, and the point is less to deconstruct it than to reground it. Now artifice is used to make reality appear actual again, to render the real––after all the derealizations of new media and political lies––effective as such. Sometimes one almost senses a utopian impulse in this project. This signals yet another shift, from an anti-aesthetic position of a generation ago to a renewed insistence on the beautiful, which now appears almost as a space of hope or at least of refuge from an otherwise oppressive web of traumatic histories. However, this new position isn’t uncritical: for instance, many artists today highlight glitches in our media world, breaks that might loosen us from our status as human programs subject to ceaseless testing and technological reformatting, moments where failure is indeed only human.

This brings us back to my title. I suggested that essays are only attempts, more or less failed. Critics also fail artworks in the sense that there can never be one definitive reading; this surplus is yet another attribute that sets art apart from other things in the world. But there’s also a way––and this goes back to the call to historicize––in which artists can’t help but fail their historical moments as well. Like a myth according Claude Lévi-Strauss, an artwork can’t resolve the contradictions that prompt it for the simple reason that they exist beyond its ambit. Yet in this very failure these contradictions are often glimpsed nonetheless, and in this flash of historical consciousness failure can count as success. There’s a double temporality here. On the one hand, this consciousness usually occurs in retrospect, hence the need for “reckonings.” On the other, the failure can serve as a prompt for future work, even further illumination. Try again, fail again, fail better. Or, as Beckett also says, “Nohow on!”

Excerpted from Fail Better by Hal Foster. Copyright © 2025 by Hal Foster and published by MIT Press. Reprinted with permission of the author.

Reviews:

“Fail Better is a masterwork, offering us the companionship, across the years, of a superlative mind. Foster’s work continues to create new geometries for thinking about art, and around art, and across an ever-shifting reality. I love the steady wildness of thinking here, the radical wit, the blooms of transformation and the way that a special seat is held open for the unpredictable guest of paradox.” — Rivka Galchen, staff writer for The New Yorker

No responses yet