It had only taken about 2,000 years, but according to a 1924 headline in The New York Times, apparently “the end of quests for the Holy Grail” had arrived. That year Swedish-American polymath Gustavus Eisen published a multi-volume work on the “Antioch chalice,” an artifact discovered in 1910 by excavators in present-day Turkey and sold to an influential art dealer, Fahim Kouchakji. Eisen argued that the chalice was none other than the cup of Christ used at the Last Supper — the Holy Grail.

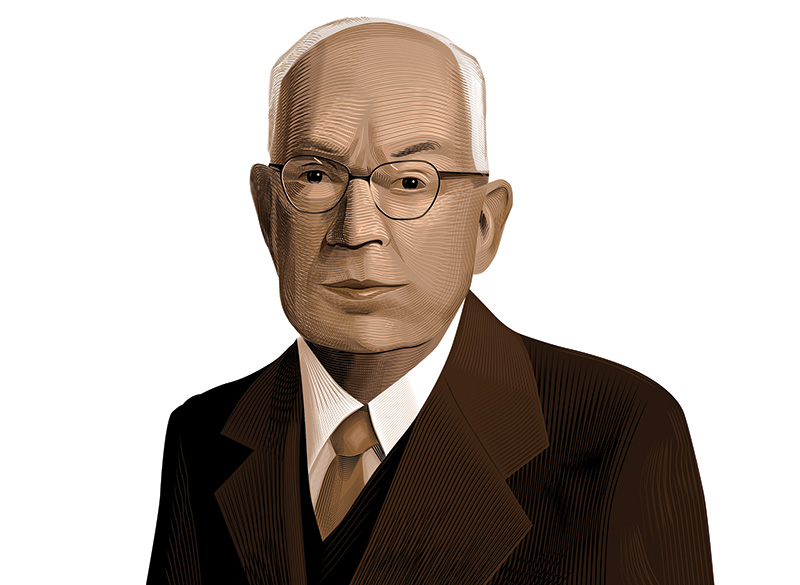

Not so fast, cautioned Princeton art and archaeology professor Charles Rufus Morey. “Archaeologists are likely to be troubled by certain discrepancies which appear when one examines the technique and style of the chalice,” Morey wrote in a 1924 essay in The Daily Princetonian.

Morey was an esteemed figure in the field of art history. He earned his reputation with a Vatican curator when he suggested that if a seemingly medieval ivory was taken apart, they would discover a recycled consular diptych, a commemorative Roman artwork. In a 1957 PAW article, David F. Blair ’40 wrote that Morey “evidently spoke with such assurance that the attempt was made, and of course he was right.”

In 1917, Morey founded what is now called the Index for Medieval Art, a comprehensive catalog of Christian, Jewish, and Islamic art of that period. The index’s original collection started in two shoeboxes and, according to the 1957 article, was initially funded in part by “Morey’s ability at the pool table of the Nassau Club.” Today, the index hosts 200,000 entries in the physical archive.

Later in his career, Morey was a force behind Princeton’s role in the Antioch expeditions of the 1930s, which uncovered many Roman mosaics, several of which reside with the Princeton University Art Museum. After World War II, Morey served as cultural attaché at the American Embassy in Rome, where he became a leader of the “Monuments Men” who sought to repatriate Nazi-looted artifacts to their respective countries of origin. When the Metropolitan Museum of Art enlisted Morey for help in acquiring two statues from Italy for the museum’s 1946 diamond jubilee, Morey arranged for the battleship USS Missouri to transport the sculptures.

Eisen, however, was a Renaissance man of influence. According to SFGate, among his varied efforts, Eisen promoted the conservation of giant sequoias and introduced avocados to California. Eisen’s book not only claimed the cup was the Holy Grail, but that the cup’s ornamentation, which possibly depicted the Twelve Apostles, was more than simply iconography. In his view, the figures were tantamount to portraits, “the only known representations of the founders of Christianity made by a person who had actually seen them.”

Morey considered this claim rubbish, explaining that the cup’s ornate enclosure probably dated to the fourth century A.D. “This discrepancy should cause some reserve in accepting the chalice as an early Christian work,” Morey wrote in 1924. “A dating in the first century seems to me in any case quite impossible.” Contributing to modern doubts, the Holy Grail was not the only famous drinking vessel the antiquities dealer Kouchakji claimed to have on hand. He also linked his gallery’s Raqqa pottery to ceramics mentioned in A Thousand and One Nights.

Morey’s counterargument failed to stop the chalice from capturing the popular imagination. It was exhibited at the Louvre in 1931 and two years later at the Chicago World’s Fair. The Met acquired the artifact in 1950. According to The New York Times, influential Met director Thomas Hoving ’53 *60 once joked that the chalice was “too ugly to be a fake.”

In the end, both Eisen and Morey missed a big revelation. Modern scholars have determined the chalice is not a cup at all, but an oil lamp of the sixth century. So far, none have claimed it belonged to Aladdin.

No responses yet