The Roaring ’20s witnessed the triumph of the automobile — from ubiquitous Fords to opulent Pierce-Arrows. As the president of the American Automobile Association declared in 1921, “The motor car ... must now be regarded as an instrumentality which has established its worth and can no longer be regarded as a superluxury.”

But as cars became a fixture of daily life, they also transformed the way it was experienced, much to the chagrin of some Princetonians. “The time has certainly come when automobiles should be prohibited once and for all from coming on the Campus,” wrote senior Neilson Abeel in 1925 in a letter to The Daily Princetonian.

“Not only is it most impossible to walk from one building to another without being run over or spattered with mud, but it is impossible to get to sleep at night because of the infernal noise.”

In the wake of that year’s houseparties, the Prince observed that there appeared to be a car in Princeton for each of the weekend’s 750 guests and that while this congestion was anomalous, “the plea that cars be excluded from the Campus has other virtues,” not least the preservation of Princeton’s grass.

President John Grier Hibben 1882 *1893 apparently agreed. On May 14, he announced that effective May 18, “all automobiles, carriages, and motorcycles” would be barred from campus, “except in cases where necessary for business purposes.”

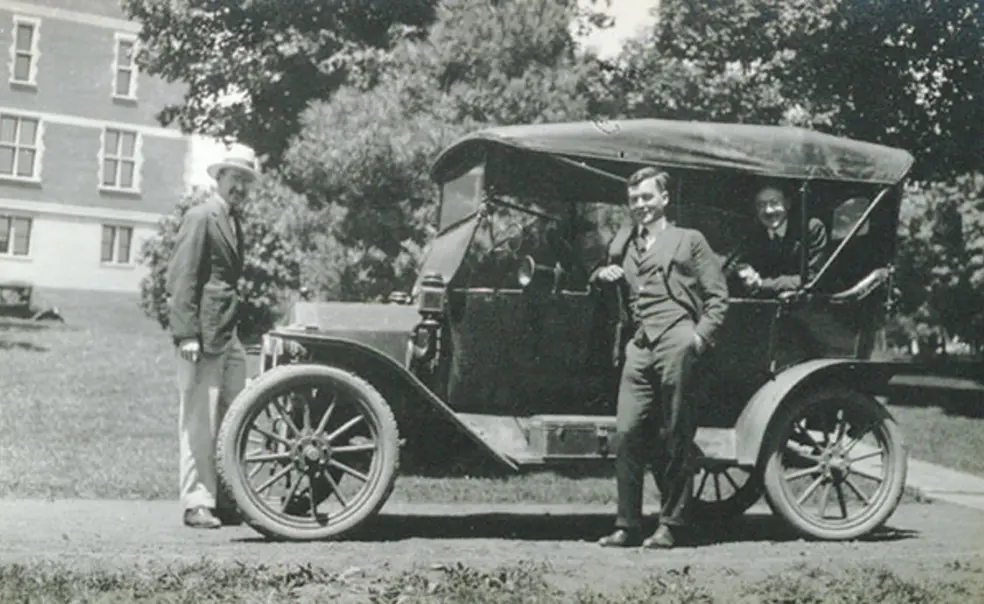

Needless to say, the decree was unwelcome to owners of these vehicles, and on the eve of its enforcement, they staged what the Prince described as “a motor P-rade of over 50 cars ... crammed with undergraduates and followed and watched by hordes of spectators.” Abeel, whose effigy waved from the leading vehicle, was the object of much derision, and Hibben, who felt constrained to publicly absolve Abeel of any part in his decision, endured a clamorous drive-by at Prospect House. But the ban on undergraduate cars, which has varied in restrictiveness over the years, persists.

John S. Weeren is founding director of Princeton Writes and a former assistant University archivist.

3 Responses

Neilson Abeel k'1925

7 Years AgoThe Ban's Main Perpetrator

I was very amused that my father, Neilson Abeel, is still recognized as a main perpetrator of the ban on cars in 1925. I am only sorry that you could not find a photograph of his effigy. He entered Princeton with the Class of 1924, and due to health issues took a year off and graduated with the Class of 1925. After marrying my mother in 1936 he never drove again, much to her irritation.

My father’s other notable campaign was to get Princeton to ban evangelist Frank Buchman from preaching and holding meetings on the campus. President Hibben was the final authority in that instance as well. In light of the current debates over the freedom of speech on academic campuses, I am not sure that the Buchman ban would pass the First Amendment test today.

Richard Trenner ’70

7 Years AgoBanning Cars on Campus

I impute nothing greater than irony to the following sad postscript to “Autos Get the Boot,” on the decision in 1925 by Princeton President John Grier Hibben 1882 *1893 to ban “all automobiles, carriages, and motorcycles [from campus] except in cases where necessary for business purposes” (That Was Then, May 16).

Eight years after his decree and only one year after his retirement from the University — on May 16, 1933 — Hibben and his wife were motoring back to Princeton from Elizabeth, N.J., when their car collided with a truck on wet pavement. The president died while he was being transported to the Rahway (N.J.) Hospital; Mrs. Hibben died from her injuries a few weeks later. They were buried in Princeton Cemetery.

Martin Schell ’74

7 Years AgoBanning Cars on Campus

“Autos Get the Boot” only reveals the tip of the iceberg, namely banning the presence of cars on campus. The broader issue that emerged was whether students were permitted to use cars anywhere in the borough. This student “right” has had many ups and downs in the past century, leading the Princetoniana Committee to discuss its history in some detail during 2006–07.

Restrictions occurred in steady increments beginning in 1926-27, starting with a required permit from the superintendent of grounds, to a permit from the dean of students, to an outright ban on driving cars, to a ban on merely riding in cars (1934–35 catalog).

The impetus to restrict a student’s right to drive in Princeton off-campus was safety. Committee members Frank Sloat ’55 and Bruce Leslie ’66 recalled explanations given by their fathers (classes of ’29 and ’33, respectively) that the loss of several scions among the student body to fatal car accidents prompted President Hibben to get even stricter.

The temper of the times extended to campus issues beyond automobiles. In 1926–27, the University Catalog’s section titled General Orders was renamed General Regulations, with a new subsection titled Campus Regulations. That addressed not only cars but also moral issues such as women entering a dorm room. It is interesting to consider how this new form of transportation technology and its concomitant tragedies led to stricter rules in other aspects of campus life.