Take a walk around campus at Princeton and you will surely see signs of school spirit everywhere: A tiger here, black and orange stripes there, maybe even the University shield proudly displayed by someone strolling by Nassau Hall. The emblems of the University are ubiquitous here, plastered on baseball hats, laptops, backpacks, and bicycles.

But did you know that since 1987, Princeton has held a trademark on every piece of University merchandise sold, from T-shirts and sweatshirts to phone cases, cuff links, and glassware? Anything adorned with the Princeton “P,” Princeton tiger, or even the Latin motto has been vetted by the University to ensure it meets the quality expected under the school’s trademark. In the Oct. 14, 1987, issue of PAW, alumnus David Williamson ’84 explained a new era for tigers, that emblematic letter “P,” and black and orange stripes.

Princeton ™

By David Williamson ’84

(From the Oct. 14, 1987, issue of PAW)

What’s in a name? An 8-percent royalty, if the name belongs to Princeton University. Plagued by an explosion in the unauthorized use of the University’s logo, shield, name, and symbols, Princeton decided this summer to institute a registered trademark program. As of Sept. 1, the name “Princeton University,” the colors orange and black used together, the letter “P,” the Princeton tiger, and the University shield (including the Latin motto “Dei Sub Numine Viget”) are being protected as federally registered trademarks. Any manufacturer wishing to use these logos on a product has to pay the University an 8-percent royalty on net sales and attach the ™ or ® symbol, to the product.

“Actually, the purpose of the program isn’t to make money off Princeton’s name,” said Jean Mahoney, manager of technology transfer in the University’s research and project administration. “We’re really only trying to protect our trademark, enforce quality control, and curb abuses of our logos.” Under federal law, Mahoney said, an institution such as Princeton owns its trademark without having to register it. Unless the University enforces its trademark, however, its exclusive control over its logo could be weakened.

Of course, maintaining exclusive rights over a symbol like the tiger — the mascot of more than 100 other colleges and universities — is difficult. In processing trademark applications, Mahoney said, the University would seek to protect trademark rights on those products which were obviously targeted at the Princeton market or were trading off the Princeton name. “A sweatshirt with ‘Princeton’ written on it in the school color of Princeton High School would not come under trademark,” she said. “But something in orange and black would. Also all the products should include the ™ and ® symbols, no matter how small.”

With the new trademark program, manufacturers wishing to use the Princeton name on a product must apply for permission. In the past, Mahoney said, all manufacturers were supposed to ask permission but few did; with the tremendous increase in Princeton-labeled products, she said, a trademarking program became necessary.

Manufacturers must reapply for trademark permission each year. The University is requiring a licensing fee of $100 per product, with a minimum of $400 in guaranteed royalties per year. Along with each application, a manufacturer must also send a sample of his product.

In the past month, Mahoney’s office has sent out 75 packets of information about the program and has received about 25 different items, with most being approved following the completion of a standard trademark-royalty agreement. (In-house organizations are not affected by the trademark policy.)

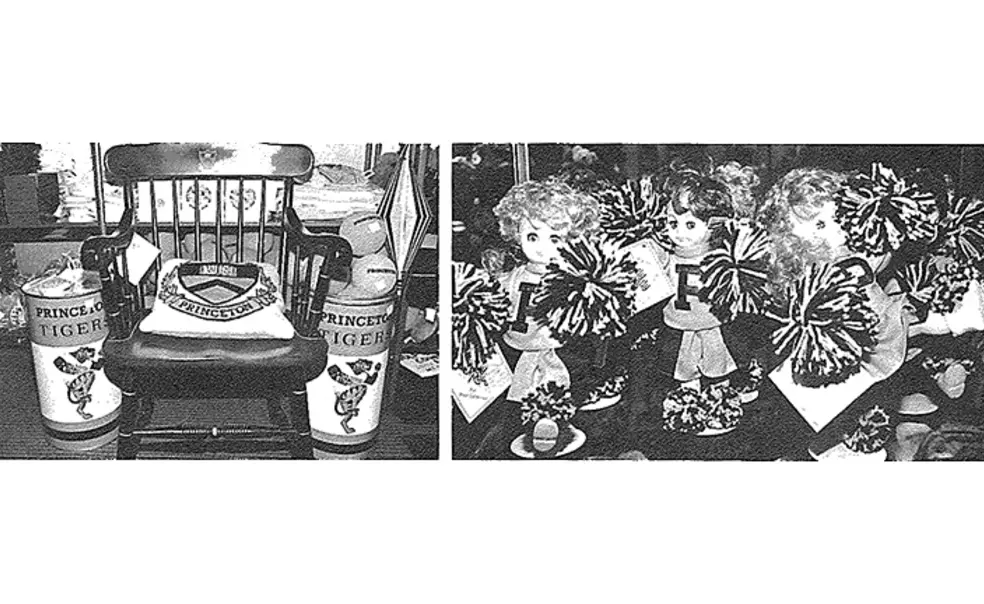

Remarkably diverse products bear Princeton trappings. The most common are the clothes, such as sweatshirts, T-shirts, and shorts, many of which are sold at the University Store but produced by independent manufacturers. There are also more esoteric items — Princeton windsocks, Princeton champagne glasses, Princeton golf balls. All must be registered. Even limited-production specialty items are affected. The Thomas Sweet ice cream and confectionery store in Princeton, for example, produces chocolates shaped like the University shield; under the trademark protection program, the store owes the University 8 percent on each $1.50 of chocolate sold.

Only one University logo is strictly off-limits to commercial use — the University seal, which is in the custody of the Secretary of the University and is, in effect, the corporate seal of the Board of Trustees. Mahoney said that she discovered one company manufacturing 24-kt. gold blazer buttons bearing the University seal and denied them permission to use it, forcing them to discontinue production.

Princeton’s trademarking program is not unusual for institutions of higher learning. Some schools, like the University of California at Los Angeles, have been collecting off their trademarks for more than 20 years. According to Mahoney, other Ivy League schools besides Princeton are moving toward trademark protection.

Mahoney added that it was too early to determine how much money would be generated by the University’s enforcement of its trademark. Other schools with similar programs have collected between $50,000 and $200,000 annually. At Princeton, the funds collected will be put into a special account, although no decision has been made yet on how the money will be spent. For the time being, the biggest problem the University’s trademark program faces is finding all the unauthorized users of the Princeton symbols. Mahoney said that she would appreciate being contacted by any alumni finding items bearing unauthorized University trademarks.

“The main thing is to protect our trademarks and the University’s reputation,” she said. “We want to see correct usage of our name.”

No responses yet