Banner year for endowment as investment return jumps

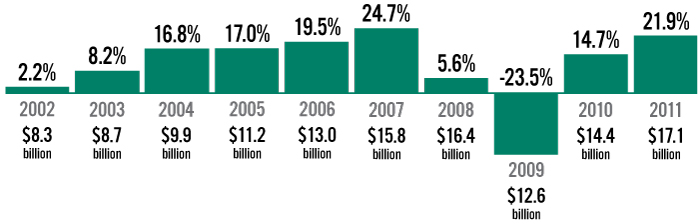

Princeton’s endowment soared to an all-time high — $17.1 billion — in the year ending June 30, rebounding strongly after losing nearly a quarter of its value in the global financial crisis. The University’s investments returned 21.9 percent, surpassing the $16.3 billion peak reached before the financial crisis hit in 2008.

By mid-October, those gains had been eroded somewhat as concerns about the U.S. economy and Europe’s debt crisis drove down financial markets. Andrew Golden, president of the Princeton University Investment Co., which manages the endowment, estimated in an interview Oct. 14 that the University’s investments had lost 2 to 5 percent of their value.

“It’s tougher sledding,” Golden said. “Our losses are less than markets overall. But they’re non-trivial.”

Still, the gains represent a notable turnaround from the financial crisis, when global markets collapsed and the endowment lost about 23 percent of its value in the 2008–09 year. In response, Princeton adopted a broad range of cost-saving measures. It cut spending and increased revenues in order to generate about $170 million in budget savings. It temporarily stopped merit raises for employees making more than $75,000 and reduced the hiring of visiting professors as well as tenured and tenure-track professors. It also reduced its 10-year capital-spending plan from $3.9 billion to $2.9 billion.

The rebound in the endowment has freed the University of some of those constraints, though senior Princeton officials say they still are being disciplined. “We needed a rebound in endowment value in order to avoid additional cuts, so we cannot relax the budget discipline we imposed over the last two years,” Provost Christopher Eisgruber ’83 said in an email.

The University has resumed merit raises and the hiring of new faculty, but with a watchful eye, Eisgruber said. “Salaries are lower now than they would otherwise have been because most faculty and staff went without raises for two years,” he said. “The number of searches for tenured and tenure-track faculty that we are doing this year is higher than it was during the last two years, but still not as high as it was in the years preceding the recession.”

Officials are hoping to roll several projects back into the capital plan, given lower-than-anticipated construction costs, and a presentation will be made to the Board of Trustees in January. One goal: Renovate 20 Washington Road, the old site of the Frick chemistry lab, which now could house international programs and the economics department.

Princeton aims to spend between 4 and 5.75 percent of the endowment on its annual operating budget. As the endowment declined, the University breached the upper range, hitting 6 percent in 2009–10. With its rebound, Princeton spent 5.1 percent in 2010–11 and plans to spend 4.4 percent in the current academic year.

The University has created an “insurance fund” that would provide a source of cash in a crisis. Ultimately, officials want to have as much in cash as would be required to fund the University for one year. During the crisis, Princeton borrowed $1 billion at attractive rates to help fund operations. It has been fully spent and will be paid back over 30 years.

Only one Ivy school topped Princeton’s endowment return in the last fiscal year. Columbia posted a 23.6 percent gain, while Yale matched Princeton’s performance. Harvard saw a 21.4 percent gain, followed by Penn (18.6), Brown (18.5), Dartmouth (18.4), and Cornell (17).

Over the past 10 years, Princeton has averaged an annual 9.8 percent return.

Driving last year’s success were investments in companies in fast-growing developing economies such as China and India. These investments returned 35 percent. The next-biggest winner was investments in stocks in developed countries (aside from the United States), which returned 33 percent. After that, the University’s private-equity assets — money invested in companies that aren’t publicly traded — fared best, returning 31 percent.

That was particularly “satisfying” to Golden, who faced questions in the financial crisis about why Princeton would make investments in companies that might not pay off for many years. “Back in the dark days of the post-Lehman era, people were asking, ‘Why did you tie your money up this way?’ ” Golden said. Princeton’s response: “Because in the long term we think it provides a return benefit.”

Rounding out the endowment’s portfolio, U.S. stocks gained 30 percent, real assets such as real estate and natural resources gained 14 percent, and fixed income gained 2 percent. Independent-return funds — which bet on specific circumstances such as whether a biotech company will get approval for a drug — enjoyed a 14 percent increase in value.

Looking forward, Golden plans to invest even more in developing countries, raising the endowment’s allocation in that area from 9 percent to 11 percent. He is reducing the allocation in developed countries from 6.5 to 5.5 percent and in U.S. stocks from 7.5 to 6.5 percent. Other allocations are not changing — independent return (25 percent), private equity (23), real assets (23), and fixed income (6).

Golden has been working to develop more investment contacts in foreign countries. “That’s been part of a grand unifying theme to get more money in the hands of foreign locals,” he said. “Because if they are reasonably good investors, they should be able to have an edge compared to someone based in the U.S. in terms of the intimacy of the details and nuances of information.” He noted that he spent more time in China in the last year — about three weeks — than in New York City.

Golden said he doesn’t necessarily expect the University’s endowment return in the last year to be replicated anytime soon. “It may be a little high. This rebound is quicker than we may have expected,” he said. “Some of that was simply the bounce back from what had been an overreaction on the downside.”

No responses yet