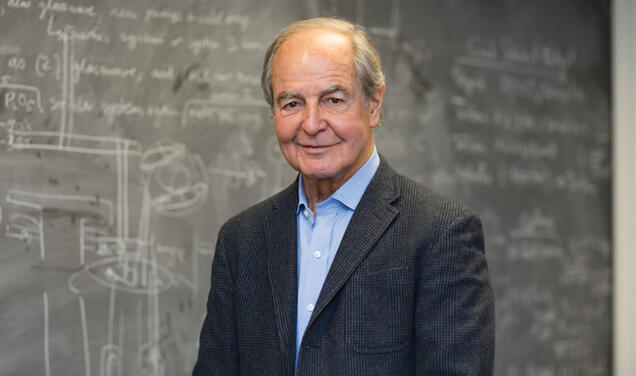

Anna Arabindan-Kesson

Arabindan-Kesson is illuminating the intersection of medicine, race, and art

At the age of 6, Anna Arabindan-Kesson moved from Sri Lanka to the city of Geelong, Australia. She recalls being the “first nonwhite kid” at her new school and quickly became interested in the dynamics of race. This focus continued as her family moved again to New Zealand, where she completed high school and studied nursing.

“I was trained by a lot of indigenous nurses, so as a 17-year-old I was reading critical race theory and learning about colonial history,” she explains. She adds that what struck her were “the assumptions and associations we make about people just based on how we see them.”

After supporting herself for several years as a nurse, Arabindan-Kesson went back to school for a humanities degree and instantly felt a connection between her medical background and the field of art history. As a nurse “we’re trained to see, to look very closely, to read bodies, to make diagnoses,” she says. “There’s a connection to what one does as an art historian.”

Arabindan-Kesson focuses on the intersection of medicine, race, and art, often shining a light on connections “that are there but aren’t seen” and trying to parse how these connections affect us in the present.

Quick Facts

Title

Associate Professor

Time at Princeton

9 years

Recent Class

Introduction to Pre-20th Century Black Diaspora Art

Arabindan-Kesson’s Research

A Sampling

Pictorial Prescription

While teaching a course on colonial medicine in 2020, Arabindan-Kesson was struck by the ways medical and racial histories were visualized across the British empire. For example, one drawing, called The Torrid Zone, depicts Jamaica as a realm of “deviant cross-racial intimacy” with a dangerous, disease-producing climate. “Art history can help us really understand how an object, artwork, or image works,” she says. Arabindan-Kesson co-founded and co-leads Art Hx, a website that publishes short essays about colonial-era visual materials that “can help us understand these entangled histories” of medicine, race, and art. She is currently working to expand Art Hx’s virtual artist-in-residency program.

How Plantations Shaped Health Care

Arabindan-Kesson is working on her second book, tentatively titled An Empire State of Mind: Plantation Imaginaries and British Colonialism, about how colonial plantations, in America and abroad, were spaces that cultivated developments in both landscape techniques and medical imaging, while also reinforcing the concept of racial difference as “fixed and hierarchical.” For example, Arabindan-Kesson notes that plantations were constructed by clearing away existing vegetation and indigenous communities to produce open spaces that would allow overseers to view enslaved people without obstruction. “That idea of seeing clearly is so important to developing both landscape techniques and medical frameworks at the time,” she says.

Mapping Black Art in Italy

As a 2022-23 recipient of the Rome Prize, which supports advanced independent work in the arts and humanities, Arabindan-Kesson spent last summer tracing the movements of American-born Black artists in Rome during the 19th century. She put together a Black artists walking tour, mapping where these antebellum artists may have traveled and what the environment might have been like for them. “It was really amazing to try and trace how they might have moved in a world outside the politics of the U.S.,” she says. Arabindan-Kesson plans to continue this research in Florence in the summer of 2025.

No responses yet