Ben Baer Translates Feminist Activist’s Words

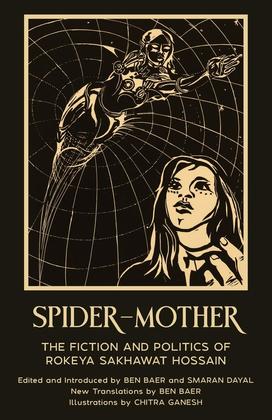

The book: Spider-Mother features the writings of Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, a pioneering Indian Muslim feminist who became a prominent writer, activist, and educator despite her lack of formal education. Her essays, newly translated by Ben Baer, reflect on her experiences with gender oppression, segregation, and more. Despite these challenges, Spider-Mother (Warbler Press) offers hope as Hossain’s activism demands dismantling gender supremacy to create a world where all people can be free.

The editors:

Ben Baer is an associate professor of comparative literature and director of Princeton’s Program in South Asian Studies. His research focuses on the diversity of literary and political figurations and concepts of Indigeneity, primarily in South Asia and the Americas. He translated The Tale of Hansuli Turn and is the author of Indigenous Vanguards.

Smaran Dayal is an assistant professor of literature at Stevens Institute of Technology. A scholar of American and postcolonial literature, Dayal is co-editor of Fictions of America: The Book of Firsts and is working on a book titled Afrofutures, Atlantic Pasts.

Excerpt:

The first—and still the most vivid—biographical account of Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain portrays her at one point as a “spider-mother” (a makar-mata or makarsa janani). There is nothing sinister in this metaphor. The spider is a figure for the unconditional labor of care and guidance performed by an educator for children that are not her own kin. “Day after day in this way, with the blood of her own breast, spider-mother began to revive hundreds of baby spiders into new life,” writes Shamsunnahar Mahmud (1908–1964), a younger co-worker in the girls’ school Rokeya founded. Her Rokeya Jibani (Biography of Rokeya) appeared in 1937, five years after Rokeya’s death. Rokeya’s life was shadowed by death: her two daughters died in infancy, her husband died before she was thirty years old, she mourns the beloved elder siblings who took it upon themselves to educate her, and she records examples of the meaningless deaths (literal and social) of countless women in her writings. Yet:

None of Rokeya’s own children survived. But she made exteriority into a home. In the 25 years of the Sakhawat Memorial School’s life, with the blood of her own breast, she raised the innumerable children of other people into humanity.

Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain (1880–1932) was a major feminist intellectual and activist of the 20th century and — we are convinced — a voice that translates into the social, political, and cultural environment of the twenty-first. While her writings and institution-building activities are very much of their time and place (colonial India between 1902 and 1932, the span of Rokeya’s public interventions in her lifetime), their energy and imagination searchingly reach and call beyond that time and place. They speak to renewed and increasingly universalized urgencies concerning relations between the “religious” and the “secular.” They have things to teach us about contemporary debates and conflicts that focus on women’s education and emancipation in the non-West and beyond, about persistent misperceptions of Islam as a monolithic bloc, and about the forms that social struggle and critique can take when those who struggle are deeply implicated in and shaped by the very systems within and against which they try to work. This last point is perhaps the most significant: where, she asks, does the (Muslim) feminist woman stand in relation to the script of sexual difference by which she has been written and which she has internalized?

The parenthetic “Muslim” in the last sentence is intentional. It signifies that Rokeya’s mindset and ethics were importantly determined by specific practices and tenets of a Muslim household and community, and that Islam remained an indelible spiritual and intellectual resource throughout her life. But it also signifies that she refused to allow her critique to remain limited to a single community or religious idiom. Being Muslim is something she struggled with in both senses of this phrase: first with it, using it, as an enabling instrument of reasoned thought and ethical relation. She often invokes Islamic scriptural support for her arguments about women’s rights and emancipation, and her work represents an important intervention within this discourse that has many subsequent echoes.

And second, in the other sense, against it as a system of instituted social practices she believed were perversions of the originary ethos of Islam. Of the perversions, her object is the sex-gender system of (especially upper-class) Muslim society, and in particular the system of sexual segregation/female seclusion and the artificial stupefaction of women by denying them education. As Rokeya knew, and as she repeatedly pointed out with incisiveness and great wit, neither sexual apartheid nor denial of developed intellectual capability to women are problems restricted to Muslim societies alone. To blame them on something called “Islam” is therefore not only factually incorrect, but it also blocks the potential to forge links and solidarity among women of different backgrounds. She thus used the specificity of her own experience and formation to configure a feminist practice (educational and literary) that could speak to much more general and common systems of sex-gender oppression and inequality. The essay “Burka” in the present volume is a good illustration of this, but you can find it everywhere in her writings. The inner knot or complexity of her life and work is in the problem of identifying, naming, disclosing the outlines of a system that is in fact so large and pervasive that as such it is not susceptible to an overall description (i.e., simply to call something “patriarchy” — a word Rokeya does not use — evidently does not solve the problem). That shifting, spectral system inhabits us all, men and women (today we would add queer, trans, and nonbinary) in ways we cannot fully know or recognize. And this poses a problem of speech. It is from within this space that Rokeya speaks and asks to be read and heard.

Rokeya was born in 1880 into an upper-class and conservative Muslim landholding family in rural north-east Bengal. Twenty-three years after the Indian “Mutiny” and the subsequent transferal of Indian sovereignty from a private capitalist corporation to the British state, and five years before the founding of the Indian National Congress that would eventually lead the country to a negotiated independence in 1947. Her formation was in many ways typical for women of the rural Muslim gentry in her time. As Roushan Jahan has observed, strict sexual segregation and female seclusion in Indian Muslim society of the time were markers of class status. It was extremely expensive to maintain a household with separate women’s quarters and to supply many varieties of body-covering clothing and shielded transportation. Purdah was a symbol of prestige and a moral imperative internalized and accepted by men and women alike. Moreover, it was to some extent observed within nearly every other religious community in the subcontinent (Hindu, Parsi, Christian). To this practice of seclusion, we must add the uneven nurturing of a certain general social separation of Muslim communities in her generation and the preceding one. This separation or social siloing was partially determined by the aftermath of the so-called Mutiny. This was an experience of defeat for Indian Muslims who had previously constituted the prevailing indigenous ruling class, and the changes included a shift away from Persian as the language of state administration and commerce. The post-1857 years were both a period of retrenchment, occasional rebellion, and reorganization for elite Indian Muslims, but the aftermath also entailed a new sense of community isolation and individuation that had specific effects on gender relations as signifiers of communal difference. Both the British legal system and a variety of — again class-fixed — Hindu, Christian, and Parsi social reform movements were in the 19th century loosening restrictions on women’s visibility and mobility, but upper-class Muslim society tended toward a more limiting set of norms for Muslim women despite the more liberal Sharia prescriptions for women’s rights regarding marriage, divorce, and property. Regarding the matter of class and self-acknowledged status, Rokeya’s familial genealogy was ashrafi. That is, an old lineage of elite migrants from Persia whose traditions and language had a complex relation of differentiation from those of the region where they made their homes. Even as they lived among (and often ruled over) a Bengali-speaking population for generations, many ashrafs used Arabic, Persian, and Urdu as languages of choice and deprecated Bengali as a tongue and as a non-Islamic cultural formation. The language spoken in Rokeya’s family home was Urdu, and the daughters rote-learned some Arabic through memorization of scripture without knowing the meaning of the words they were repeating.9 As in many similar situations, women were positioned and ethically obliged to be specific kinds of symbols for the preservation of the integrity and legacy of the community’s lineage and self-understanding.

From the start, therefore, Rokeya’s experience and position placed her in a complex double bind that she was obliged to navigate on a daily basis for her entire life: as an insider on the outside and an outsider on the inside (as a woman and as a Muslim; as a Muslim woman becoming a Bengali Muslim feminist; as an elite Muslim woman subject to restrictions that her social privilege in fact allowed her to transgress and question; such knots can be multiplied). This navigation — in its many twists and permutations — constitutes the “text” or spiderweb of Rokeya’s life, and it can be read in each of the writings we present in this volume.

Excerpted from Spider-Mother. Copyright © 2024 by Warbler Press. Reprinted with permission.

Reviews:

“Groundbreaking…vitally relevant today…fine translations of these important texts.” — Amitav Ghosh, author, most recently of Smoke and Ashes: Opium’s Hidden Histories

“A gorgeous, urgent compilation of the feminist, decolonizing vision of Rokeya Hossain, and of her understanding that the best speculative fiction poses a challenge to the violence of the present.” —Siddhartha Deb, author of The Light at the End of the World

No responses yet