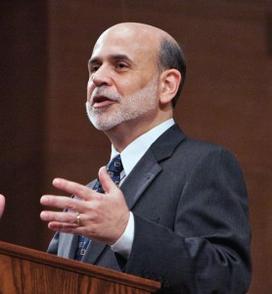

Bernanke Speaks About Challenges of Chairing the Fed

“The biggest thing I’d ever run before [the Federal Reserve] was the economics department at Princeton, so there were a lot of new things to think about,” Ben Bernanke said in a speech at McCosh 50 on April 2. While his work as department chair gave him “a lot of experience working with prima donnas,” Bernanke said that leading the Fed was filled with new challenges. “The thing that surprised me the most about the job was how much of it involved dealing with political figures,” Bernanke said. “The Fed is independent and apolitical, that’s very true — there were no politics in our decision-making. But it’s still very important for the Fed to coordinate with and explain itself to Congress and the administration.”

Bernanke was invited to campus by the Whig-Cliosophic Society to receive the 2014 James Madison Award for Distinguished Public Service. Past recipients of this award include Golda Meir (1974), Bill Clinton (2000), and Antonin Scalia (2008). In presenting the award, Whig-Clio Treasurer Aaron Hauptman ’15 praised Bernanke for applying his academic background to inform his decision-making as chairman

“Mr. Bernanke is the paragon of Princeton’s unofficial motto, ‘Princeton in the nation’s service and in the service of all nations,’” Hauptman said.

After accepting the award, Bernanke took part in a question-and-answer session with former Fed vice chairman and Princeton economics professor Alan Blinder ’67, who opened by asking about Bernanke’s transition into public service.

“I spent my career studying monetary policy and economic history and I felt I could make a contribution and, if I could, I should,” Bernanke said.

Blinder also asked about the Fed’s decision to let Lehman Brothers fail in 2008, pointing to this as the biggest headline from the Fed during Bernanke’s tenure. Bernanke stressed that there was a broad consensus among economists to let Lehman fail, and, in the end, the Fed did not have much choice in the matter. “We knew very well it was going to be disruptive, perhaps more disruptive than we anticipated,” Bernanke said. “But there was never a time when we sat down and said ‘Here’s a way we can prevent Lehman from failing, should we do it or not?’ We never had a moment like that.”

The conversation moved on to the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), signed into law in 2008 by President George W. Bush to empower the government to buy up assets and equity from financial industries in order to strengthen the financial sector. Blinder asked about the public’s negative perception of this so-called “bank bailout.”

“TARP was, perhaps as Barney Frank put it, the most unpopular successful program in the history of the United Sates. It was hugely successful — it stopped the financial crisis, it helped the economy recover, and it made money,” Bernanke said. Unfortunately, Bernanke noted, success does not translate to widespread acceptance. “There are still Congresspeople who are having trouble from their constituents because they voted for it.”

No responses yet