Bill Bradley ’65 in Biography

When William Warren Bradley graduated in June, as one of the most publicized—almost overpublicized—athletes of his generation, one wondered what further heights he could attain: would he graduate retire to the dusk of fading press clippings, to be remembered only as a sort of male Shirley Temple, as what he once ironically referred to as “Old Satin Shorts”? The answer as of this week is no, since on September 27th, he became one of the very first personages in history who was the subject of a biography at the age of 21. A perceptive, well-rounded profile it is too, and perhaps not since Pindar wrote his Ode to the young athlete Chromios has there been a comparable tribute (John McPhee, A Sense of Where You Are, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, $3.75).

Bradley’s Boswell is John McPhee ’53, appropriately enough a former Alumni Weekly “On the Campus” reporter and Class Secretary who has gone on to write for Time and the New Yorker. He got interested in writing about Bradley through his father, Dr. Harry R. “Mickey” McPhee, recently retired University Physician and for many years caretaker of Princeton athletic teams, but only if the subject would cooperate. He told Bradley that it was not his intent to show merely how phenomenal he was at basketball but to explain what basketball itself was all about, to give “a sense of the game.” The result is not so much cooperation as collaboration, and Bradley spent many patient hours setting out game situations “with chairs as opponents, shooting imaginary basketballs at imaginary baskets on wallpapered walls.” McPhee also visited the Bradley home last summer in Crystal City, Missouri, a kind of modernized Mark Twain river town where Bradley senior is the bank president.

“An Old Pro”

The portrait of Bill Bradley that emerges will surprise and perhaps shock some of the more naïve of his fans. He comes out “an old pro,” the product of pre-college professional coaching and basketball summer schools, a schoolboy All-American recruited by hundreds of colleges who at first decided on Duke. John McPhee was a forward, despite his somewhat stumpy proportions, at Deerfield, Princeton (freshmen) and Cambridge University, becoming thereby forcibly acquainted with hip and elbow work, and with clinical pleasure describes “the subtle felonies” which constitute successful basketball. He takes particular satisfaction explaining the narrow path between right and wrong Bradley follows in the “Graceo-Roman wrestling” under the backboards, and in the captions under the excellent set of action photographs points out Bradley’s various shadings of the rules. Of the rough tactics he would have to endure in some future professional career, McPhee says, “there’s nothing the pros could show or teach him.”

What is especially intriguing is Bradley’s technique—the expertise of the completely dedicated craftsman who practices endless hours until all his moves are completely instinctive. For McPhee he shot baskets with his back to the backboard; that was easy, he said, because with enough training you develop “a sense of where you are.” At the Lawrenceville gym one day he kept missing and decided the backet was an inch and a half low; McPhee got a ladd fuer and measured it, and that’s what it was. Basketball is the only contact sport which can be “learned” alone, without other players; but the problem is, as one of his coaches from schoolboy days, an ex-professional, is quoted, “Where did this kid get his dedication? Why did he decide to make the sacrifices?”

The irony of McPhee’s book is that when he wrote the long New Yorker profile—which in expanded form is one of the six chapters—he assumed that Bradley’s athletic career was over, sinch for all his excellence Princeton was not in the same class as the other teams in the postseason tournaments. But he was forced to back his typewriter, to write an account for the rest of the season, when the whole team started to play like little Bradleys. The end of that trail (and of the book) was the amazing 118-82 game against Wichita in Portland, when Bradley scored 58 points, the last 16 without a miss in the last five minutes.

What attracted McPhee to him, however, was not just his phenomenal basketball ability, but the fact that it was not so much given as it was created—as a product of, to use Bradley’s two favorite words, discipline and concentration. Whether basketball itself was worth quite that much effort, some would dispute; in any case, the discipline, concentration and dedication remain and can be turned in other channels. “The most interesting thing about Bill Bradley was not just that he was a great basketball player, but that he succeeded so amply in other things that he was doing at the same time, reached a more promising level of attainment, and, in the end, put basketball behind him because he had something better to do.” He feels that religion is the main source of his strength, teaches Sunday School and speaks to youth groups from Taiwan to Witherspoon Street on the virtues of sacrifice and discipline. After Bradley-like labors he received a first group on his thesis for the History Department, graduated with honors, and instead of opting for a career in professional sports, applied for a Rhodes Scholarship.

In June, Crystal City greeted him with a “Bill Bradley Day,” in which a $13,000 fund was raised for college scholarships (characteristically, academic scholarships are open to both boys and girls). Over the summer the rest of Missouri became familiar with his voice as a radio newscaster. On October 1st he sails on the Queen Mary with the Rhodes continent, to “read” Politics, Philosophy and Economics at Worcester College for two years.

A recurrent question among his acquaintances is exactly when will he “become Governor of Missouri.” If he does, we can be sure John McPhee will be there to write Volume II of this excellent little book.

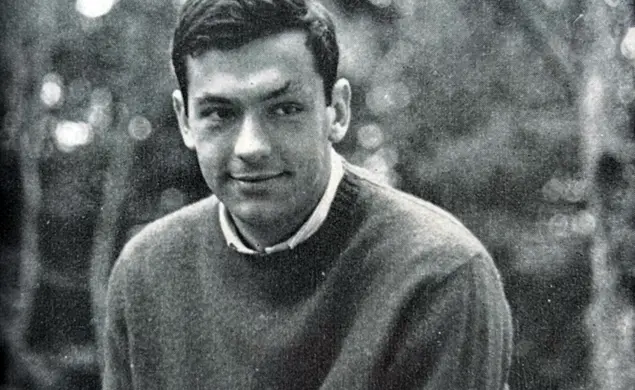

Now that Bill Bradley had joined the immortals of Princeton’s athletic history, his giant photograph hangs alongside those of Hobey Baker and Dick Kazmaier in the bar of the ‘Nass.’ The picture above was taken while he was hiding out last spring from publicity and press in the Princeton home of his biographer, John McPhee ’53. Like all unsigned articles in PAW, this review was written by the Editor. –E.D.

This was originally published in the September 28, 1965, issue of PAW.

No responses yet