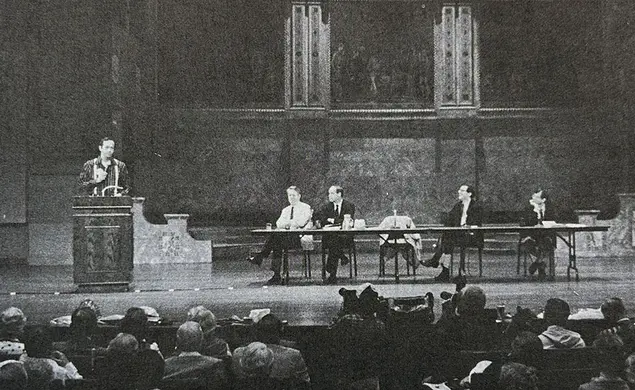

Bill Bradley ’65 on Tax Reform

A Reunions panel examines how the issue arose, where it stands today, and what its prospects are in the current session of Congress.

This is adapted from an alumni-faculty forum on tax reform held at last June’s reunions. The participants were Bill Bradley ’65, a member of the Senate Finance Committee and a leader in the tax-reform effort; Steve Forbes ’70, deputy editor-in-chief of Forbes magazine and three-time winner of the U.S. Steel “Crystal Owl” award for accuracy in economic forecasting; Roger Mentz ’63, assistant secretary of the Treasury for tax policy; and Harvey Rosen, a professor of economics at Princeton who specializes in tax matters. The moderator, Wilson School Dean Donald Stokes ’51, asked the panelists to consider three major questions: how we got where we are in the area of tax reform, what we ought to do now, and how likely we are to do it.

Bill Bradley ’65:

Tax reform is an issue whose time has come. It actually started back in 1980 when I convened a small group—including Roger Mentz ’63, by the way—to start thinking through the present tax system and see if we couldn’t come up with a better approach. In 1982, we produced the Fair Tax Act, the Bradley/Gephardt Bill. About two years later two Republicans, Jack Kemp and Bob Kaston, came up with another bill that headed in the same direction: lowering tax rates dramatically and eliminating a lot of the tax expenditures. Then in December 1984, the Treasury came out with its massive tax reform study, and President Reagan embraced the concept and committed the Administration to do something in 1985. Last May, Treasury II was announced, the President made a nationwide address and clearly placed himself behind the issue, and for the first time since 1962, when Jack Kennedy did it, a President of the United States backed a specific and dramatic tax reform proposal.

There are several rationales for tax reform. One is economic, and it goes to the issue of how do you get America to full employment—defined as about 4 percent unemployment—and hold it for the long term in a growing world economy. One of the things that’s required, it seems to me, is that we be able to compete effectively in that growing world economy. And that means two things: making sure that we look out for the stability of the world trading and financial system, and making sure that we have the most efficient allocation of resources domestically. The question then is: which is the more efficient allocator of resources—is it members of the Senate Finance Committee and the House Ways and Means Committee, or is it the market? I believe it’s the market, and what we try to do with tax reform is to remove the tax code from between investor and ultimate investment so that capital will flow to those areas of the economy that have real value in the marketplace. Then the investment will not only generate jobs and create wealth, but will also enhance our comparative advantage internationally. That’s the theoretical rationale for tax reform.

The common-sense rationale is simply that if tax rates are cut dramatically and if you earn more, you’re going to keep more. That means for so many middle-income families today a kind of economic freedom that they have not experienced in recent years. It means the ability to protect themselves from the uncertainties of economic life today by their own efforts.

There is in addition a cultural rationale, which I think is probably best expressed by each of your reflecting on your own personal experience. If you were one of those Americans who filled out your own income tax return just a few months ago, perhaps the scene is familiar: It’s one o’clock in the morning on April 12. You have your papers strewn out all over the kitchen table or, if you have a particular complex return, the dining-room table. You are saying to your spouse, “Now who has that piece of paper that shows we have a capital loss carried forward. Is your mother-in-law a credit, an exclusion, or a deduction? Does it make a difference if she lives in the house, or in the condominium we own, or in the apartment we rent?” You were probably scratching your head and saying, “There’s gotta be a better way.” Indeed, the cultural rationale for tax reform is that the present system is so complex that very few people understand it, and that there is a general perception that the system is unfair, and by that I mean that equal incomes just do not pay equal taxes. A few statistics: The average tax rate paid by people who made more than $1 million in income last year was 17 percent. The average tax rate for middle-income families in the $30,000-$40,000 range is close to double that. Last year a family making $29,000 could pay $3,500 in taxes, $2,000 in taxes, or some paid nothing in taxes. In other words, you look at the guy next door who’s making about the same income that you do, and you believe that he’s getting a better deal than you are in the tax system, somehow, because he knows how to game the system.

Last year, another statistic, 8 million individuals took their tax returns to professional tax preparers in order to have the short form filled out. There are more people in the tax preparation and strategizing business than teach English in all the colleges of America. There are more people in the tax preparation and strategizing business than serve in the Marine and Air Force reserves combined. Last year, the value of all tax expenditures was about $370 billion; in 1967, it was $37 billion. That makes this the biggest and fastest-growing program in the government.

The perception that there is something wrong with the tax system is deep and strongly held. Before giving a speech about a year ago, I was sitting on the dais with an executive from one of New Jersey’s most respected companies, and he said to me, “You know, I’ve got a problem with my son.” Well, that’s a threshold comment. But I was up for re-election, so I asked “What is the problem?” And he said, “My son is 25 years old and he’s worked for a corporation for two years, and all he can think about is how to avoid paying taxes, how to game the tax system. I’ve told him, ‘Look, learn your profession, work every day, and move up the ladder, pay your taxes, don’t worry about that.’” And then he made the telling point. He said, “You know, Senator, I am concerned that there is a whole generation out there that is growing up with no sense of responsibility to support the legitimate functions of government. They believe they have no responsibility.

This goes to the core of our tax system: voluntary compliance. We’re different from many other countries around the world. Historically, our citizens have believed that they should pay their fair share of taxes. But with the size of the underground economy in this country—which is now the seventh largest economy in the world—with stories like the one which that executive conveyed to me and which each of you have experienced, the cultural rationale for tax reform is that the present system has eaten away at the underpinnings of trust that are central in a democratic society.

So there’s economic rationale and a cultural rationale for tax reform, but I work in Washington, at least a couple of days a week, and a lot of things make economic sense and cultural sense that never happen in Washington because they don’t make political sense. My argument, however, is that tax reform, particularly this year, makes political sense for both parties, and that’s why there’s a real chance it will occur. What’s in it for Republicans? Well, if you were a Republican strategist and you saw Ronald Reagan take landslides in ’80 and ’84 largely with Democratic voters who switched over, you’d want to keep those Democratic voters. And what tax reform allows Republicans who voted for Ronald Reagan for what I call cultural, social, “I’m feeling good” reasons in 1980 and 1984, and appeal to them with an economic issue that is in their direct self-interest—lower tax rates over time, that knowledge that if you earn more, you’ll keep more for yourself and for your family. Among certain Republican strategists that is viewed as a realignment issue, an issue on which Democrats become Republicans. That presumes, of course, fervent Democratic opposition, which I hope won’t and don’t expect to see, occur.

What’s in it for Democrats? It gives the Democratic Party, for the first time in 15 years, a specific proposal that it can advocate which is pro-economic growth. Indeed, it is an issue that allows Democrats to argue for economic growth and equity simultaneously. It is the tax system that is unfair, and the route to making it more fair is lowering tax rates at the same time you eliminate many of the tax expenditures, the result being a fairer income tax system and more economic growth. It takes Democrats back to 1962, which is where we were when Jack Kennedy, as I said earlier, was the last President to put his name on a specific tax reform proposal that did many of the same things as this one—cut rates, eliminate loopholes. So tax reform not only has an economic rationale and a cultural rationale, it makes political sense.

But this is an issue that must have bipartisan support in order to pass. And it poses a question that is fundamental to our democracy and that had been posed from the inception throughout the Constitutional Convention and the Federalist Papers and is still relevant today: Is it a legislator’s job to represent the narrow interest—not make the realtors too angry, make sure the plumbers are happy, don’t make the truckers too angry, give the farmers this—or to serve the general interest, the whole? Well, I clearly believe that it is the latter, that tax reform serves the general interest over the narrower interest, that both Republicans (some) and Democrats (some) see the tax issue in that way, and that therefore tax reform poses a much more fundamental question than the debate has, up to this point, revealed about our system of government and the American character.

For all those reasons, I think this will be the year that we will get major tax reform. To be sure, it will not be easy. $370 billion worth of tax expenditures means that the recipients will be vigorously defending their right to continue to receive that government subsidy. Ultimately, for tax reform to occur will require bipartisanship, aggressive Presidential leadership striking the right themes—economic growth and opportunity, fairness and family—and the active involvement of people throughout the country who decide that it’s time that their voice be heard. I think this will be the year, though it will not be easy and it is far from certain, but I think it’s a fight worth making.

This was originally published in the October 9, 1985 issue of PAW.

No responses yet