Bill Bradley ’65, We Hardly Know Ya

Despite volumes of publicity, the epitome of the scholar-athlete remains an enigma...

A few months ago, Bill Bradley ’65 became the first among his classmates to retire from his principal business. The newspapers report he has earned more than $2.5 million in his 10 years as a professional basketball player, a per annum rate that few of his Princeton friends will ever match. He has written a popular book about his life as a pro, traveled widely around the world, married, fathered a child, and generally achieved more than the most ambitious person hopes for in a lifetime. But he has not yet done everything that he wants to. He said he looked forward in his retirement to changing his baby’s diapers. That will likely drive him in short time to a career in politics.

Late one night during the final week of the basketball season, the New York Knickerbockers, the team with which he spent his entire career, were being televised from some distant city, it might have been San Antonio. The Knicks were struggling through a disappointing season and Bradley was playing very little, averaging only about 4 points a game, well below his career mark of more than 12 a contest. Midway through the first quarter, he checked into the game. The announcer remarked this would be his last television appearance (the cameras were closing out their season, too) and in a few days he would play his final home game in Madison Square Garden.

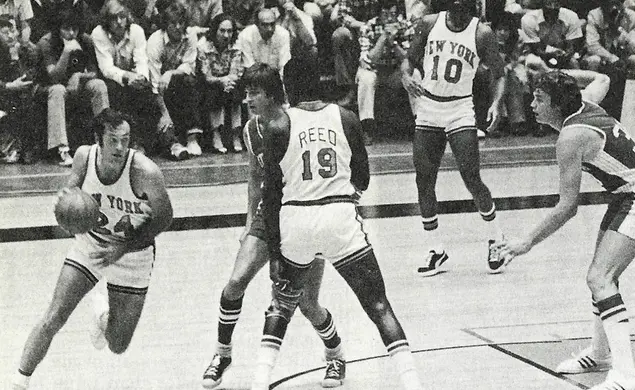

As Bradley entered the court, the camera zoomed in on his face, revealing perhaps more forehead than was visible when he played at Princeton. The arched eyebrow was there, and so were the force of habit and cunning, which in lieu of speed and youthful stamina propelled him through the next few minutes of play. His professional reputation was built on his accurate shooting and his understanding of how to move on offense without the ball. When the Knicks were champs back in 1970 and 1973, they played an exciting style: swift movement of the players and the ball, accurate shooting, tight resourceful defense. “Hit the open man” was their guiding wisdom.

On this night, Bradley ran the length of the court full-speed. On offense, he cut in and out of the foul lane, circling the defense, stopping and starting, trying to shake his man long enough to get open for a pass. But the ball seldom traveled his way. Too often, it became the property of one of New York’s slick but uncomprehending guards who seemed determined to advance it to the basket without benefit of his teammates. The Knicks had become a tiresome and unsuccessful team. It was hard to imagine that the game played this way could not any longer excite Bradley.

At Princeton, the ball had always returned to Bradley’s hands; no matter how hard he might try to send it elsewhere, it inevitably came back. A renowned high school player, he fell out of the sky onto campus, having decided to attend Duke, then in the 11th hour, changing his mind and enrolling at Princeton. In his first week at the university, he went right to work in tiny Dillon Gym, performing daily his drill of firing up a succession of shots from different spots on the court, never changing position until he was satisfied with his marksmanship from that location. He didn’t have the shiny muscles usually required of candidates for basketball fame, and he looked scrawny (like an upside-down coathanger, someone was to say). Nor did he yet have a jump shot to speak of, but he quickly lived up to his advance billings. By sophomore year, Princeton fans were squeezing into Dillon to watch him, overflowing the stands onto the floor where they sat within arm’s distance of the court.

In college, Bradley used a wider assortment of shots than he did in the pros. His hooks were the favorites of the fans and, when he lofted a rare left-hander through the basket, the noise of the crowd filled the gym. After the games, the fans replayed his shots and passes, and defended the possibility that he was not a dominant rebounder or as speedy afoot as others. They described his best plays as if they were objects of art and should have been hung in the Dillon trophy case.

As conspicuous as he was in the gym, he was inconspicuous on the campus. In the Ivy League manner, his fellow students affected not to care inordinantly. The university was a place where a basketball star was only another student, even if he was 6’5”. His classmates learned about him through his close friends, or from the media. In his senior year, an alumnus named John McPhee ’53 did a long profile about Bradley which appeared in the New Yorker. He entitled it “A Sense of Where You Are.” Students passed the magazine from one to another as if it were Playboy.

Rumors about his life made the rounds, so many rumors that it was impossible to know what he really did. He spent his Saturday nights after games in the library. No, he has studied in a small room in the basement of West College, a hideaway lent to him by someone in the administration. After one game, he returned to his room and discovered a woman there. She refused to leave so he called the proctors—so the stories went. His classmates groaned at such self-denial and said it couldn’t be true, but it was Bradley, and it had to be true.

In his final game at Princeton, before the sudden leap to glory in the NCAA championships, his classmates gave him the bell clapper from Nassau Hall as a token of their esteem. Princeton had no pep rallies in the conventional manner where members of a team deliver short talks, so it was the first time he had ever addressed a Princeton sports crowd. It was an emotional moment, but he didn’t choke up or become maudlin. He accepted the clapper and thanked everyone and calmly departed. In some ways, his classmates hardly knew him, but they were to owe their identity as a Princeton class to him. In the years immediately following, as they scattered over the world, they became used to hearing the questions, “Were you in Bill Bradley’s class? What was he really like?”

He might have been then, in 1965, the biggest white college hero of the decade, certainly the last Christian scholar-athlete of what was the end of an era. He was the culmination of everything that young athletes growing up in his generation should be true of all athletes. Even kids from Scarsdale and other affluent suburban communities could relate to him. As McPhee had pointed out, Bradley had overcome the advantage of being a banker’s son, who spent his childhood winters in West Palm Beach, to excel in a game where increasingly the best players were black from the poor side of the tracks. As he departed for Oxford to study as a Rhodes Scholar, a different kind of athletic hero came to New York to begin his career as a pro quarterback-Joe Namath, who flouted the conventional norms of training and public behavior, and emerged as a popular anti-establishment figure, a role that seemed to fit the changing times.

In the late ‘60s, the New York Knicks began to play Bradley regularly and became the most prominent team in the sport. As the Knicks rose to the top, more unsubstantiated stories about Bradley went around: he turned down all commercials, even one (agonizingly, it was said) on behalf of the American milk industry; he owned an island in the Aegean Sea; he was the highest paid forward in the pros; he drove a Volkswagen—one day, enroute to the Garden, he had stopped at a light when he noticed on either side of him a splendid Rolls Royce, and in each, his teammates, Walt Frazier and Earl Monroe, both convulsed with laughter at the sight of Dollar Bill, as New York fans had nicknamed him, scrunched up in his Volks.

Frank Sowinski ’78, Princeton’s current sharp-shooting forward, lived near Bradley in northern New Jersey and spent a few weeks one summer practicing with him as they both prepared for their approaching seasons. He was amazed to see how hard Bradley worked. Not wanting to feel embarrassed that a man 10 years older could outlast him, Sowinski had exhausted himself. For an hour each night, they practiced full speed and at the end it was always Bradley who seemed stronger, ready to play more. Sowinski had discovered another side of Bradley, too. One time, he feinted Bradley out of position and drove by him toward the basket; he was clear for the shot, he thought, then suddenly he was entangled in Bradley’s legs and falling. Sowinski learned other little tricks from him.

Each year reporters asked Bradley if he were going to stop playing. Would he go to Harvard Law School? Was it true that he planned to run for governor, for congressman, for senator? Was he writing a book?

Bradley continued a relationship with Princeton although he resisted efforts to become deeply involved in traditional alumni activities. He returned to town to visit McPhee and his expository writing classes, and to practice with the Princeton basketball team. He accepted some of the many invitations to address alumni groups around the country, and he helped when he could with basketball recruiting.

Someone at Princeton conceived an idea to honor Bradley anew. The Knicks were scheduled to play an exhibition in Jadwin. In its infancy, the giant gym has been called the house that Bradley built. The crowds of the Bradley era had further revealed the inadequacy of the old gym, and construction of a new fieldhouse had begun just after he left campus. The idea was to award Bradley the keys to Jadwin in a brief ceremony before the game. On the eventful night, in the midst of his warm-up, Bradley was summoned to midcourt to receive the honorary keys. After the presentation, a microphone was handed to him. He spoke a few perfunctory words and handed the microphone back. He turned toward the Knick bench, tossed the keys to a trainer, and went back to shooting.

His last engagement at Princeton was more successful. This past September, he was invited to address the Honor Assembly of the Freshman Class, the annual meeting at which the responsibilities of the Princeton Honor Code are passed onto the new students. He had responded to the invitation with his customary caution, thinking about it for some time before accepting. When he entered Alexander Hall that night, it was packed with week-old freshmen and scores of longtime Bradley-watchers. The audience rose and gave him a long ovation. When he finished speaking, they clapped vigorously.

Afterwards, he joined them for a beer reception in Dillon. The Knicks had just opened their training camp and he was working hard to get into shape. He passed up the beer for a soft drink. He took off his coat and loosened his tie and went out onto the main court to talk to the freshmen who thrust their hands forward to shake his. After a half hour, it was time for him to leave. He walked out of Dillon alone. Passing by some parked cars, he turned and went over to one. He stretched out his arms, leaned against the car roof, and slowly brough one leg up under his chin, repeating the exercise with the other, then bending and touching his toes. He did this one or two more times, and then he was gone, into his final season.

A few nights after the San Antonio game, Bradley appeared for the last time in the Garden. He played his customary role, but during the fourth quarter he was pulled from action. The game stopped, and a referee came over to give him a basketball and to shake his hand. The crowd rose to its feet clapping. A minute passed, another, then another, and the clapping continued. A long-distance runner named Dr. George Sheehan once wrote about athletes and life and death: “The athlete becomes more and more as he has less and less. And in the course of this becoming, he has already died the little deaths, has learned how to accept the inevitable, has even taught himself what death will be like when it comes. For the athlete, death has no sting. He has had the great initiation.” Reporters watching Bradley that night wrote in the newspapers the next morning that tears welled up in his eyes and he found it difficult to speak.

This was originally published in the July 11, 1977, issue of PAW.

No responses yet