Bill Bradley ’65 On Why He Came to Princeton

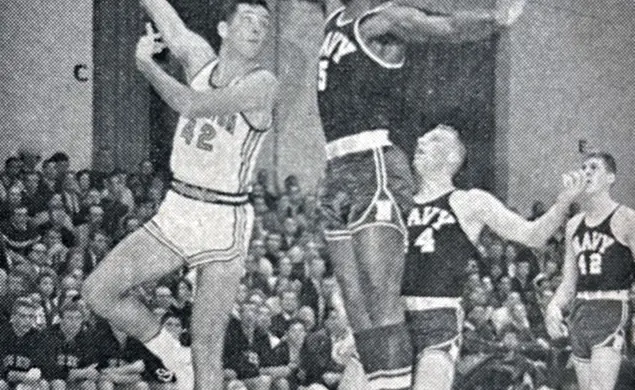

There are two numbers that really mean something to the Princeton man. One is his class numeral, especially every fifth year, when the reunions are biggest. The other is more universal—42. It became famous on the back of All-America Tailback Dick Kazmaier some 11 years ago, and the wearer may be a little less hallowed at Princeton than such fellow graduates as F. Scott Fitzgerald and Woodrow Wilson—but not much. Naturally, with the proper regard for tradition, 42 is no longer worn by Tiger football players. But now, according to Princeton enthusiasts and a lot of less biased observers, the orange and black 42 is likely to be retired from the basketball court, too. The prodigy who will be responsible for this is Bill Bradley, Princeton ’65, a 6-foot-5 ., 198-poind son of a bank president from Crystal City, Mo.

How good is Bill Bradley? “Listen,” says Coach Harry Gallatin of the National Basketball Association’s St. Louis Hawks, “I’d like to have him on my club right now.” “I thought I had him for Duke,” says Blue Devil Coach Vic Bubas, pretending to stab himself in the chest. “Every time I hear his name I get a sharp pain right here.”

In the Midwest, where they savor basketball players with all the critical attention that a gourmet gives a Chateaubriand, Bradley was considered the best high school player in the country. He promptly lived up to the rating, leading Princeton’s freshmen to a 10-4 season and sinking 57 straight foul shots, a total that broke the record of 56 set by Bill Sharman in professional NBA.

This month Bradley began his varsity career. He led Princeton to three straight victories, raised his foul-shot record to 58 straight before finally missing and made it obvious that the Ivy League has its best player in years—maybe ever.

Not that Bill Bradley wants any such notoriety. An introvert—“It was three months before I could talk to him,” says a roommate, Chuck Berling—he has approached Princeton and basketball at the same studied pace. As a high school player, he scored 3,066 points, probably a national record and reason enough for more than 75 colleges to pursue him. But he was also a straight A student, president of the Missouri Association of Student Councils and a member of the National Honor Society.

Why Choose Princeton?

When asked why he settled on Princeton, he says, “What seems to count to them is character and personality. The one thing I don’t want to be is typed. I don’t want to end up as just old Satin Shorts Bradley.”

Still, but for a broken foot, Bradley would be at Duke, not Princeton. In fact, his decision to matriculate there instead of at Duke was made at the last possible moment. In May of 1960 Bradley had made up his mind to go to Duke. Earlier, he had also made up his mind that once he made up his mind, he wouldn’t change it. During the summer, however, he broke his boot playing baseball. Out of the boredom enforced by inactivity he took to reading the myriad old college catalogues lying around the house.

Considering a foreign service career, he found himself impressed by the dossier on Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School of International Affairs. Hesitantly, an earlier interest in Princeton was revived, and he finally selected the Ivy League school. Holding nothing against Duke, Bradley still feels somewhat guilty about the switch. He is not eagerly anticipating the Duke-Princeton game. “I guess it will be good to finally get it over,” he says. Bradley lives in Little Hall, the Princeton dormitory closest to the gymnasium. This is, however, a convenience pretty much wasted on him. His mailing address would better be 2-8J Firestone Library, a study room hidden away on the second floor, where he spends from eight to 12 hours every day. “There is a fan in there, and once I get used to its drone my concentration isn’t broken by something like a pencil falling off the table,” he says.

It is this same minute concern for concentration that characterizes Bradley on the basketball court. His approach to the game is more pragmatic, scientific, and even fatalistic, than athletic. He scorns pleasant explanations like “touch” and “good eye.” “What is ‘touch’ but concentration?” he says. “A soft touch is no more than practicing the right way. All shots can be scientifically analyzed. It is really just a matter of coordinating the various movements into one smooth motion involving the eyes, the hands, the legs. With foul shots you are given time to concentrate, to pull all of the elements together.” The concentration has made him basketball’s best foul shot.

He also concentrates on his health, a concern that leads him to call himself a “semihypochondriac. I don’t complain, but I worry,” he says. Thus the common cold is more Bradley’s enemy than a 6-foot-10 opponent. In his room he has both a portable humidifier and a heater, and he maintains an array of pills for use at the first sign of a sore anything.

Healthy, and on the court, there is not much that Bradley can’t do. He can hook, drive, set, jump, run plays, rebound and pass. In fact, his coach, Bill van Breda Kolff, says he passes too much. Bradley’s only other problem is the typical sophomore’s difficulty with defense, and he is learning what is expected of him there.

At Princeton this winter a great deal is expected, for this year’s team is not a strong one. Graduation took the best of last year’s players, and Captain Artie Hyland is the only other really accomplished ballplayer on the Tiger squad.

With Bradley playing his usual style, casually spectacular, the Tigers won their first three games this season. Bradley was high scorer each time, with 28, 27, and 23 points against Lafayette, Villanova, and Army, respectively. In the defeat of Villanova—only the second time in 10 years that team has lost at home—Bradley took 15 shots, made 10 of them, sank all his seven foul shots and assisted on eight of Princeton’s 17 other baskets.

On Saturday night against Army he ran into something he will face for three years, a defense that played the rest of the Princeton team loosely, while watching him closely. The Cadets held Bradley to the 23 points but gave so much room to everybody else that Princeton won going away, 71-54. Bradley took 10 foul shots in the game, making nine. As he was about to shoot one, a piercing voice in the stands shouted “Miss it.” It must have broken even his concentration, for miss he did. But Princeton’s Satin Shorts won’t miss many in the next three years. Tradition may have to make room for another No. 42.

Frank Deford, PAW’s sports columnist last year, now has his own by-line on SPORTS ILLUSTRATED, where this piece appeared in December. Reprinted by permission of SPORTS ILLUSTRATED, Time Inc.—Ed.

This was originally published in the February 1, 1963, issue of PAW.

No responses yet