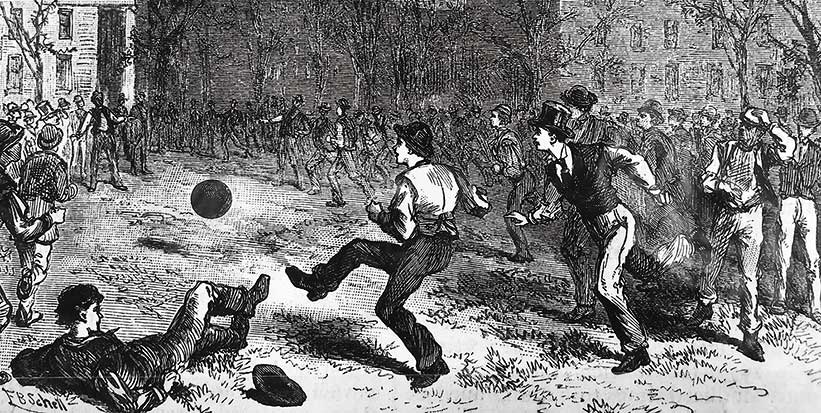

As the Rutgers student newspaper described it, the players in that landmark ball game 150 years ago battled in street clothes, bareheaded save for the Rutgers players’ scarlet “turbans.” The Scarlet Knights prevailed, 6–4. “Princeton had the most muscle, but didn’t kick very well, and wanted organization,” reported the Targum. “Our men,” it said, “were always in the right place.”

The game is credited as the first intercollegiate game of American football. But should it also be considered the first college soccer game? Or maybe the first college rugby game?

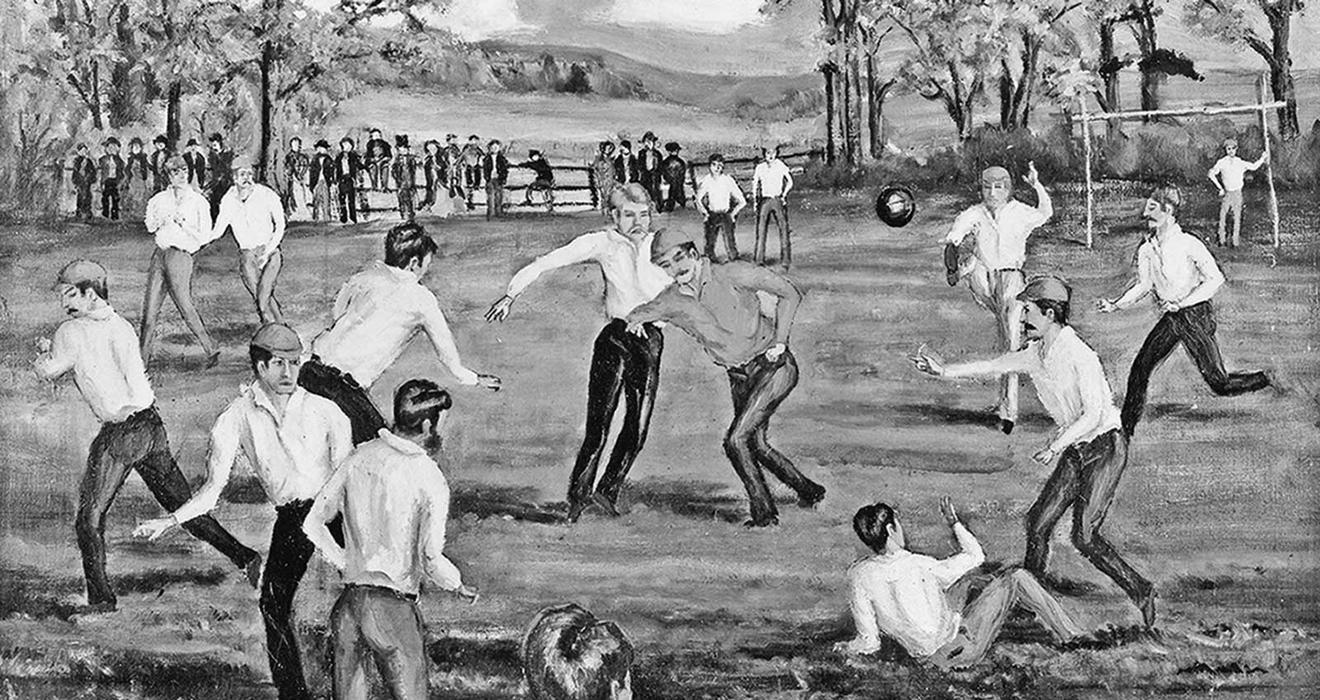

Historian Tom McCabe ’91, who teaches a course about the history of soccer at Rutgers-Newark, says that based on written accounts, soccer and rugby skills played a prominent role in the game played on the College Avenue grounds in New Brunswick. The 25-man teams used a round ball, the players moving it primarily with their feet; carrying the ball to advance it was forbidden. One early painting of the game depicts a rectangular, soccer-like goal with a goaltender in front.

“When historians look at the nitty-gritty, they’re trying to figure out what it was,” McCabe says, “because it wasn’t American college football, and it wasn’t soccer [as we know it today]. It was more of a rugby- like game.”

While Princeton football has fielded a team for 151 consecutive seasons, soccer would not become a varsity sport until 1905 (though the Princeton Theological Seminary was playing matches a decade earlier), and the rugby team was added even later, in 1931.

Princeton’s pioneering football players also made the connection to modern football in remembrances collected decades later, after the sport had become a national phenomenon. “When they’re remembering [the Rutgers game] in the early 1900s as older men, it’s all college football,” McCabe says. “They connect what they were playing to the modern college football game, and not necessarily soccer.”

McCabe has a long-running interest in soccer. In addition to playing as an undergraduate at Princeton, he researched the history of the game for one of his junior papers and returned to the topic as a Ph.D. candidate at Rutgers.

Early American football drew on similar sports then being played abroad. “There’s definitely a link to the colleges and secondary schools in England,” McCabe says, noting that American students likely read about England’s 1863 Association Rules — the basis of modern soccer — in sporting manuals and newspaper accounts.

At the same time, there were regional variations, set by the home team — kind of like kids in different neighborhoods creating games with their own local rules, McCabe says. Princeton favored a kicking game, more aligned with soccer. Harvard preferred the carrying game, influenced by rugby. And Yale developed the ball-possession game, which may have the most direct line to modern American football. (Melvin Smith, a retired meteorologist and football scholar, meticulously illustrates the process through newspaper accounts in his 2008 book, Evolvements of Early American Foot Ball: Through the 1890–91 Season.)

Dissecting the Princeton-Rutgers game, McCabe gives a legitimate claim to proponents of all three sports — soccer, rugby, and football. “It’s contested, it’s complicated,” he says. “But what grows out of it is sport as the modern collegiate spectacle that we all see today.”

And what of the heated competition between New Jersey’s best-known schools? Princeton avenged its loss in that first game in an 8–0 rematch a week later and for most of a century afterward before fortunes reversed. The centennial game in 1969 saw a Rutgers 29–0 romp, and the Garden State neighbors last met on the gridiron in 1980.

Brett Tomlinson is PAW’s sports editor.

READ MORE

No responses yet