It all began with several dozen Rutgers and Princeton students mustering on a Saturday afternoon in November 1869 to play a game won by kicking a ball past a phalanx of defenders and through the opponent’s goal. The game, in New Brunswick, marked the birth of intercollegiate football — and the start of Princeton’s rich history in the sport. In less than a quarter-century, by 1893, Princeton football was no longer a small affair played in New Brunswick, N.J., but a Thanksgiving phenomenon played against Yale, drawing 40,000 spectators to New York’s Manhattan Field.

Above, Dick Kazmaier ’52 carries the ball in a 1949 win over Yale. Two years later, he won the Heisman Trophy.

The Tigers return to New York — to Yankee Stadium — Nov. 9, to celebrate the sesquicentennial, though this time the spotlight will be shared with neither the Elis nor the Scarlet Knights, who compete in the Big Ten these days. In their place will be Dartmouth, a rival “only” since 1897. Dartmouth has figured in some of the most memorable contests in Princeton’s team annals, including the “12th Man” game in 1935, in which a fan rushed onto the field in a blinding snowstorm and tried to join Dartmouth’s line; and a come-from-behind win in 1950 that cemented a perfect season. Less happily there was the battle of unbeatens on the final day of the 1965 season from which Dartmouth alone emerged with a perfect season intact. (Princeton evened that score last November by inflicting upon Dartmouth its sole loss as the Tigers found a path to 10–0 and the first perfect season since 1964.)

The mere mention of Princeton football evokes images of raccoon coats and roadsters, the Princeton band in boater hats and black-and-orange plaid blazers leading a march down Ivy Lane, sunlight dappling gold and orange leaves, and the Tiger mascot frolicking as alumni with silver hipflasks and excited kids in tow streamed through the vaulted archways of a packed Palmer Stadium. Perhaps no alum was a greater football fanatic than F. Scott Fitzgerald 1917, albeit usually from afar. As related later by Fritz Crisler, who coached the Tigers to perfect seasons in 1933 and 1935 and introduced the classic, three-striped winged helmets before taking that design with him to his next coaching job in Ann Arbor, Mich., he’d regularly get calls from Fitzgerald after midnight on the eve of games offering strategy tips. The Great Gatsby author was reading a PAW article recapping the season when a heart attack felled him at 44 in 1940.

Much of Princeton’s football history was made in horseshoe-shaped, 40,000-seat Palmer Stadium. When the death knell sounded for the venerable stadium in 1996, serious consideration was given to erecting a much smaller replacement on the other side of Lake Carnegie, far from the heart of campus, like some “glorified high school stadium,” grumped Athletic Director Gary Walters ’67, now retired. Wiser heads prevailed, and a $45 million, 27,000-seat successor, Princeton Stadium, rose in the precise footprint of Palmer, near the eating-club tailgaters and a mere stroll from the spires and gargoyles that fired Fitzgerald’s imagination.

The approaching game will be the 99th between Princeton and Dartmouth, which holds the edge at 49–45–4. Yale is the only other regular opponent with more wins against Princeton than defeats: 77–55–10. That includes the infamous, 14-game losing streak to the Elis that Bob Holly ’82 snapped by throwing for 501 yards and scoring his fourth touchdown with four seconds on the clock in a 34–31 win over undefeated Yale in 1981 — Sports Illustrated called it “perhaps the most thrilling game ever played at Palmer.” Against all comers, Princeton has 827 wins, 406 losses, and 50 ties over the years, including a 56–48 advantage over Harvard.

Dartmouth, like Princeton, was undefeated when they met in the famous “12th Man” or “Snow Game” at Palmer in near-blizzard conditions in November 1935, but the inclement day belonged to the home team. As the Tigers marched yet again downfield, an inebriated spectator bolted from the stands and joined a Dartmouth goal-line stand with a shout of “Kill them Princeton bastards.” It was of no use. The Tigers toppled the then-Indians 26–6 and finished off Yale the following Saturday for Crisler’s second perfect season.

The weather also played a factor in the momentous 1950 game with a perfect season on the line for both teams. Two days after Thanksgiving, 80 mph winds and torrential rain lashed Palmer Stadium as the Tigers fell behind before rallying to defeat Dartmouth 13–7. With fellow All-Americans tackle Hollie Donan ’51 and center Red Finney ’51 paving the way, Dick Kazmaier ’52 ran through the slop for one touchdown and set up the other. The graceful tailback, after Princeton’s second perfect season the following fall, landed on the cover of Time magazine and ran away with the 1951 Heisman Trophy, the last Ivy player so honored. The Chicago Bears drafted Kazmaier, but he turned them down, saying, “I don’t see anything I could gain by it.” He chose Harvard Business School instead. In 2008, Princeton retired the number 42, worn by both Kazmaier and, not by happenstance, basketball’s Bill Bradley ’65.

Of the 28 national championships claimed by Princeton, the NCAA recognizes 15 — all 1922 and earlier — tying Princeton and Alabama for second, behind Yale’s 18 (the last in 1927). The sport caught on quickly after that first Rutgers game, with Eastern schools dominating it for half a century until Notre Dame, Michigan, Ohio State, and others began their ascendancy. The unbeaten 1922 Tigers were the “Team of Destiny,” a sobriquet bestowed by sportswriter Grantland Rice after Princeton turned back then-Big Ten powerhouse University of Chicago at Stagg Field in the first college game broadcast nationally on radio. The heroes for the visitors, who had trailed 18–7, were Harland “Pink” Baker 1922, Oliver Alford 1922, and sophomore Charlie Caldwell ’25, who stopped the Maroons’ fullback on the one-foot line to secure the 21–18 win.

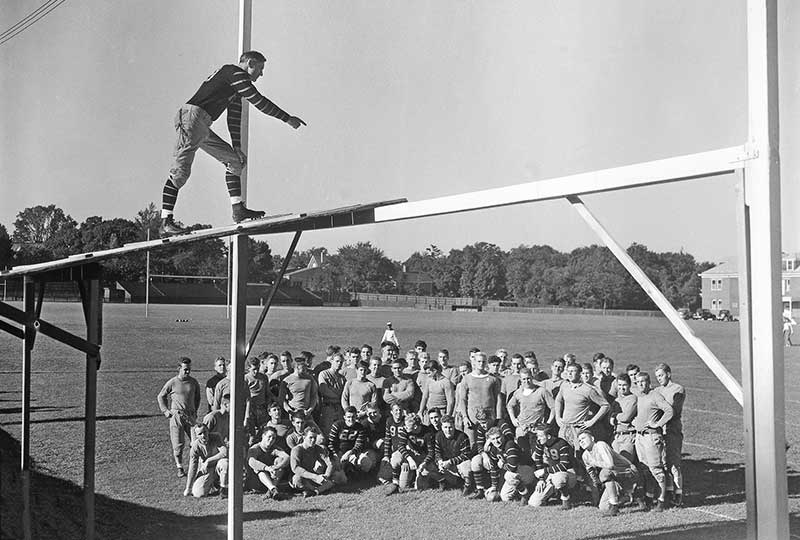

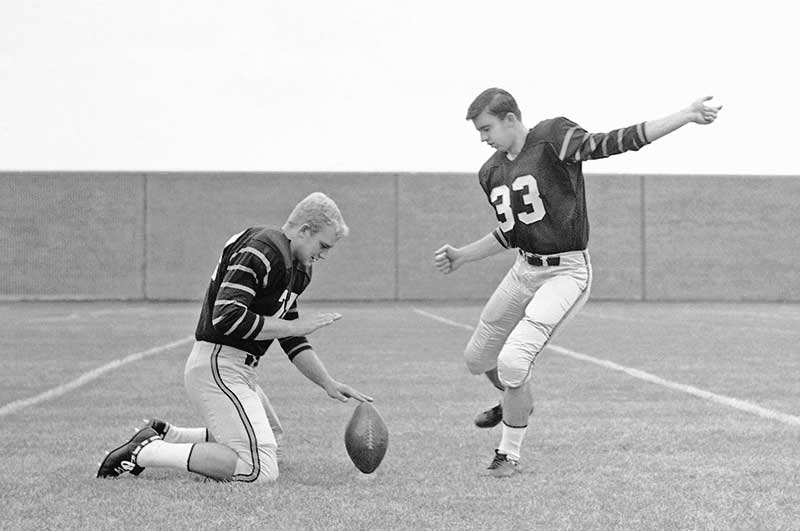

Caldwell, a three-sport athlete, returned to his alma mater to coach the Tigers in the post-World War II years. His teams reeled off 24 straight wins and 33 of 34 from the close of the 1949 season to the opening of the 1953 campaign. Caldwell compiled a sterling 70–30–3 record before Dick Colman, another maestro of the single-wing offense, took the helm in 1957, the year the Tigers won their first Ivy championship. They finished their perfect 1964 season ranked 13th nationally with All-Americans fullback Cosmo Iacavazzi ’65 *68 punishing defenders, linebacker Staś Maliszewski ’66 creating havoc, and soccer-style kicker Charlie Gogolak ’66 flummoxing opponents. Gogolak and big brother Pete, at Cornell, revolutionized the game by kicking with the instep instead of the toe, a skill they mastered as youths in Hungary before the family fled after the 1956 uprising. Charlie Gogolak kicked six field goals in a 1965 game against Rutgers and two weeks later a record 54-yarder against Cornell, which tried to stymie him with a human pyramid — two players stood on their teammates’ shoulders. The tactic was soon outlawed.

While Dartmouth’s victory at the close of the 1965 campaign snapped the Tigers’ 17-game win streak, Colman finished his tenure in 1968 with 75 wins and 33 losses. The best coaching record still belongs to Bill Roper 1902, with 89 wins, 28 losses, and 16 ties in three stints between 1906 and 1930. Roper’s squad played Knute Rockne’s Irish twice at Palmer Stadium in 1923–24, losing both. The lane between Cap and Gown Club and Cottage Club from Prospect Avenue to the main entrance of Princeton Stadium still bears his name.

So how to compare the best teams of this era to those of the past? Attendance is no contest. Last year’s undefeated team averaged 6,600 fans, with fewer than 7,800 souls at the Penn game capping the perfect season. It usually takes Yale or Harvard or a non-Ivy visitor with a local following to crest above 11,000 or 12,000 nowadays in Princeton Stadium. Some games are played under lights on Friday nights.

“You’ve got to put it in perspective and context,” says Iacavazzi, who returned to Princeton for a master’s degree in aerospace engineering after a short spell with the New York Jets in the American Football League. In the 1920s, with no television and the NFL in its infancy, “there was nothing else to do on a Saturday afternoon. You were it. You were the show. Today the NFL dominates spectator sports and I can watch pretty much any game in the country on my phone. The sport has grown in spectatorship, but it’s been cut into a million pieces.”

“The fact that there is X number of people in the stands instead of Y number is almost immaterial,” he says. “You still have great wins, terrible losses, great bonding, great teamwork. You still learn the great values.”

What’s the Princeton football game you’ll never forget?

Use our online comment form, send your story via email, or write to PAW, 194 Nassau St., Suite 38, Princeton, NJ 08542.

“We had sellouts in 1964. Guys actually scalped tickets,” says Maliszewski, but he concedes the attention his undefeated team attracted was nothing like the stir created by the 11–0 team in 1903, which shut out its first 10 opponents before Yale managed six points in the final game, making the season points margin 249–6. “When you compare us, the impact we had on American football, to the oughty-three team, those guys were on the front page of every newspaper. We weren’t,” he says.

Maliszewski, born in Poland during World War II and raised in Iowa, where his family settled as refugees, was 6-foot-2 and played at 235 pounds. Most of the program’s greats were more down to earth. Kazmaier stood 5-foot-11 and weighed 171 pounds. Iacavazzi was a battering ram, but was always under 200 pounds. There were no giants among such early legends as Knowlton “Snake” Ames 1890, golden-tressed Phil King 1893, the six Poe brothers, John DeWitt 1904, and Hobey Baker 1914.

Ames scored 62 touchdowns in 1886–89. “I don’t know how you equate the ancient records with the modern records,” says Keith Elias ’94, who rushed for a record 4,208 yards and played five years in the NFL. He tallied 49 touchdowns at Princeton but used to kid teammates, “I’m not good until I reach Snake.”

Princeton still sends players to the NFL. Linemen Carl Barisich ’73 and Dennis Norman ’01 both played nearly a decade; Dallas Cowboys quarterback and head coach Jason Garrett ’89, for seven. A steady stream is making or trying to make the jump these days, including All-American wide receiver Jesper Horsted ’19, who collared 196 passes at Princeton.

Kyle Brandt ’01, co-host of the NFL Network’s Good Morning Football TV show, after watching Horsted make an acrobatic catch in a Chicago Bears’ preseason game, declared the 6-foot-4, 225-pound rookie the greatest player in his alma mater’s history. “They’ve been playing football at Princeton for 150 years. I don’t know if they’ve ever seen somebody like this,” he said, adding later, “We’re not arriving at games on special trains anymore, but this is the glory age of the program.”

Head coach Bob Surace ’90, an All-Ivy center and a former Cincinnati Bengals assistant, might not stake such a claim. But since he started with twin 1–9 seasons, his teams have won 46 games and lost 24 and continue to attract blue-chip players, including a string of versatile quarterbacks. The crack coaching staff has groomed six Ivy players of the year since 2012, including defensive lineman Mike Catapano ’13, linebacker Mike Zeuli ’15, and quarterbacks Quinn Epperly ’15, Chad Kanoff ’18, and John Lovett ’19 (twice).

Epperly will always be remembered for two stunning wins against Harvard, spelling an injured teammate in the last minute and heaving a Hail Mary to Roman Wilson ’14 to pull out a 39–34 win in 2012, then tossing six touchdowns in a wild, 51–48, triple-overtime win against the Crimson the next year. “It was an awesome bus ride back,” says Epperly, who also set an NCAA record with 29 straight completions against Cornell in 2013. “Princeton has turned into the top school in the Ivy League if you want to play quarterback.”

As a freshman, Kanoff, who completed a record 29 touchdowns in 2017, found the football regimen “super difficult. It was way more football than I was expecting. ... The amount of mental energy you put into it, the practice hours, the meetings, expectations — you’re doing something for football more or less seven days a week for three months. It’s hard.” But the Wilson School major made the adjustment.

Lovett, signed by the Kansas City Chiefs but sitting this season out after shoulder surgery, once dreamed of playing at a big-time football school. But he now counts himself blessed for choosing Princeton and getting “an unbelievable education.”

“You’re part of a storied tradition, but a small fraternity. We carry a lot of pride wearing the uniform,” says Lovett, who is unstinting in praise of Surace for the program’s surge. “He’s such a genuine person. Obviously, he works so hard on the football aspects, but it doesn’t matter if you’re an Ivy player of the year or a scout-team player, he treats you the same. You’re his players,” Lovett says.

Elias, director of player engagement for the NFL, addressed this year’s team at summer camp. He, too, emphasized to the players they were “part of a brotherhood.” “We are going to see each other for the rest of our lives,” he said. “We’ll see each other at Reunions, at games. It’s something that will never leave us.”

It can look like a very large brotherhood on game days in Princeton Stadium, with 100 or more players dressed to play. Princeton would recruit 100 players yearly in the 1960s, and 60 when Surace played, but most quit or were cut. Now Surace and his coaches recruit a select 30. “The difference today is these kids aren’t leaving,” he says. The program invests in their success. “We didn’t have a full-time strength coach when I was at Princeton. Now we have a performance team, nutritionists, sports scientists, psychologists — people who work with our athletes as needed so they can be successful.”

Fittingly, Surace in his second season created a new tradition for Princeton football. At game’s end, the entire team runs to the corner of the end zone and, with the band playing, joins alumni in a heart-stirring rendition of “Old Nassau.” He did so not only to cement ties with the alumni, but also to improve relations with the often irreverent scramble band, and notes: “It was one of the better decisions I’ve made.”

Christopher Connell ’71 is a freelance writer based in Washington, D.C.

READ MORE

The Birth of Football ... Or Not

Views of Contact May Change Football

Quiz: Test Your Knowledge of Princeton Football Greats

24 Responses

Tommy Hanrahan ’76

5 Years AgoProud Tiger

What dreadful things Jonathan Young ’69 had to say about Princeton football! I refute all of his comments. I liked playing football. It’s a rough game. So what? No one put a gun to my head.

For the record, Princeton invented football. I’m proud we did.

Fred Doar ’77

5 Years AgoFootball: The Game Has Changed

Five years ago I wrote a controversial letter to the PAW suggesting that the University discontinue the football program because of the brain damage that the sport was inflicting on its players. I was disheartened that the football powers-that-be seemed to want to cover up the problem. Since that time, I personally boycotted the game and continued to speak out about the perils of football.

During the 2019 football season, I decided to watch a few games hoping that I would not get too depressed by all of the head cracking that the sport I played entailed. I started by watching a youth game of 10-year-olds. I was shocked. I could not count one head collision. I continued my study by watching some college games and also a few pro games. I am as surprised as anyone to report that the game has changed. They fixed it!

I think this change took a few years to implement as old coaches retired and new players were taught to keep their heads out of the collision zone. This was apparent when I watched an old film of our ’74 team. You can see the running backs diving head first through the line. We all wore neck collars so that we could deliver that head blow and not hurt our necks. We all took thousands of blows to the head.

It’s clearly a different game now, but it’s a better game. Athleticism is rewarded while brute-force helmet collisions can get you suspended for the season. Football was an important part of my life growing up, and it helped me get into the best school in the country. I feel like I can finally come back to the game I loved so much.

Bob Givey ’58

5 Years AgoPrinceton-Harvard Drama

I agree with John Drozdal ’72 about the 2012 Harvard game. Behind 34-10, it was obvious that our best chance, considering the time left (about 12 minutes) was to score three TDs plus three 2-point conversions just to tie the game. Also the Tigers had to stop Harvard three times, which seemed impossible with the Crimson racking up 500-plus yards in the game.

Amazingly, the Tigers scored 4 TDs (with three 2-point conversions) to pull the game out with 13 seconds left. Forgotten among these dramatic scores are the two Harvard kicks that failed. One was a missed extra point and the other was a blocked field goal. These gave the Tigers room to get a tie or the go-ahead score, as they did. The drama was more intense than I had seen in any Princeton football game.

Sheldon L. Smith ’64

6 Years AgoAthletes Don’t Aspire To Injure

Jonathan Young ’69’s letter describing football as a sport of “blood lust” pursued to satisfy “a certain sort of young man” and “to extract money from an older version of those men” (Inbox, Feb. 12) is both hyperbolic and myopic.

It’s doubtful that participants in football (and don’t overlook rugby, hockey, lacrosse, and wrestling) aspire to injure their opponents. And realize that wounded women are carried off in soccer, field hockey, and even basketball.

As for the University “extracting money” from gladiatorial games, Ivy League athletic attendance is so woefully small, the University probably loses money on a large majority of these events.

And I thought Yale was the bastion of Ivy sensitivity!

Don Nolte ’68

6 Years AgoA Brutal Sport

I concur with the views of my good friend Jonathan Young ’69 regarding football (Inbox, Feb. 12). Perhaps PAW could do a piece on the brain damage and other debilitating injuries that result from this brutal sport, and advocate instead for sports practiced at such institutions as Oxford and Cambridge and in the Olympics.

Editor’s note: A story about efforts to protect the health and safety of football players was included in PAW’s Oct. 23 issue and is available online at http://bit.ly/PAWfootball150.

Jonathan Young ’69

6 Years AgoQuestions About Football

In the two-page spread of letters titled “Unforgettable Gridiron Contests” in the Dec. 4 issue, I note a ruptured knee, unspecified injuries, a player “writhing on the ground,” a broken wrist, a broken nose, and a broken leg — the two last in a single game. And these are the games most celebrated in the article!

Could it be that football is a horrible travesty of a sport, pursued in order to satisfy the blood lust of a certain sort of young man, and promoted by University administrators to extract money from the older versions of those men?

Might one also bear in mind that the sentiment “We’re Number One,” as Bertrand Russell noted, has led to some extremely unsavory places in history?

Joe Grotto ’56

6 Years AgoUnforgettable Gridiron Contests

The football game our team can never forget was the Princeton-Yale game in 1954 at the Yale Bowl in front of a packed stadium (see photo above).

With less than a minute left in the game, with a 14–14 score, Princeton has the ball at midfield. Dick Emery ’55 throws a long pass to Don MacElwee ’57, who is brought down on the Yale 3-yard line. There is less than a minute remaining, with no timeouts. Royce Flippin ’56, our tailback, calls for “Goal 44” running down the field. The ball is hiked to Royce, who carries it over the goal line with blocking from Bill Agnew ’56 and Joe Grotto ’56 with only a few seconds left — as shown in the photo — for a final score of Princeton 21, Yale 14.

The next year, in the preseason scrimmage against Syracuse, Jimmy Brown ruptures the knee of Royce, our captain. Sid Pinch ’56 fills in as our tailback for our successful season; Royce comes back after his knee operation and the team beats Yale 13 to 0 and Dartmouth 6 to 3 in a snowstorm at Palmer Stadium.

The 1955 Princeton team won the Ivy League, which was not officially recognized until the following year.

Editor’s note: Bill Agnew ’56 recalls: “That photo has been on my office wall for 60 years. Joe and I worked our asses off so Royce could rest comfortably on his back in the end zone. Tailbacks get all the glory!”

Tom Meeker ’56

6 Years AgoFlippin Deserves a Mention

I am aghast at the lack of any mention of my four-year roommate, Royce N. Flippin ’56, in “150 Years of Football." Especially as the cover pictures four teammates from his class – faceless center, Jack Thompson, Sid Pinch at the far right, and Jack Kraus next to Sid.

Flip, a Montclair, N.J., athlete of the year in 1952, was recruited by Yale and Penn State among other universities for his academic and athletic prowess. However, Princeton was always his ultimate goal.

As a freshman footballer, he wore number 42, the last time any Tiger gridder would carry that number. (The following years he wore #49.) That autumn, the year 1952, he led the team to an undefeated season, marred only by a 7-7 tie with Penn in which Flip scored on a 70-yard kick return. He would score 18 touchdowns that season.

The following year, NCAA rules forbade unlimited substitution, so he played tailback and safety each entire game. In 1953 Flip ranked 11th in the nation in total offense and 16th in rushing yards. Junior year, even after missing three games with a broken wrist, he still made All-Ivy honors on the Associated Press list. His hopes for senior year were dashed in a pre-season game against Syracuse when his knee was severely injured. As captain and always a Yale killer, Flip returned in the next to last game to squash the Bulldogs’ aspirations for a championship season by scoring the first of two TDs in the 13-0 upset.

After the season, Flip was awarded the Poe Cup (now Poe-Kazmaier) for great moral character in addition to talent on the field. In later life he became Princeton’s athletic director for a number of years.

Seems to me his achievements and contributions warranted at least a mention in the article.

Clint Van Dusen ’76

6 Years AgoRemembering Iacavazzi

During the sixties, my father (Francis Lund Van Dusen '34) would take me and my brother Frank '71 to Tigers' games. I'll never forget Cosmo Iacavazzi, and what a great name!

In one game, he was tackled by a team of adversaries all standing up. Before the refs could call the down moot, Iacavazzi clawed and kneed his way to the top of the bodies below and ran away with the ball!

I can't remember if he played only defense or offense. If he was defense, he must have recovered a fumble on his way up. I can't remember the year of that season.

I wish I could go to that NYC commemoration game. Have fun!

Tom Brennan ’07

6 Years AgoMemorable Game, Momentous Day

Certainly the most memorable (or momentous?) Princeton football game was against Penn my senior year, Nov. 4, 2006, at Princeton Stadium. The match turned out to be a thrilling double-overtime victory made possible by an improvised lateral on a critical fourth and goal. That play ended up on ESPN’s top plays of the weekend; but for me, it is just a personal footnote to the larger event of the day — being introduced to a sophomore I’d later marry.

Editor’s note: John B. Canning ’65 similarly remembers the Yale game in 1962 “not because of any outstanding plays (although Princeton won) but because my blind date for the game was a young lady from Smith College whom I wound up marrying and to whom I’ve now been married for 51 years!”

Gerry Skoning ’63

6 Years AgoAn All-Time Record

Hearty congratulations on the wonderful article by Christopher Connell '71. It’s a real gem, thoroughly researched and beautifully written ... a really engaging and fun read for all.

I’m sure it stirred vivid memories of gridiron glories for generations of Princetonians, as it did for me. I had flashbacks to our football classmates who were Ivy League co-champions with Dartmouth in the 1963 season.

And, during that championship season, my classmate, tailback Hugh MacMillan ’92, set a record with a 92-yard punt return against Colgate on Oct. 19, 1963. The fact that the record still stands today is a real testament to his achievement!

Thank you to Mr. Connell for reviving these powerful memories of football in the old Palmer Stadium.

John Drozdal ’72

6 Years Ago2012: Princeton 39, Harvard 34

No contest: Oct. 20, 2012. Princeton 39, Harvard 34.

With about 12 minutes left in the fourth quarter, the Tigers trail the Crimson 34–10. With fans leaving the stadium, my wife asked, “Do you want to go or stay?” Princeton had the football and I said, “Let’s see what they do on this drive.” The next play they scored, and made the two-point conversion. I said, “We’re staying. This could get interesting.” It did! With two more touchdowns, the Tigers get it to 34–32. Here are the three things I will never forget:

1. Harvard has 4th and one yard to go. They line up to go for it, and the Harvard quarterback is using every trick in the book to draw Princeton offside. The Tiger defensive line sat there like blocks of cement. Harvard has to punt.

2. With fourth down and the Tigers deep in their own territory, Connor Michelsen ’15 goes back to pass and gets sacked. I’m thinking, “That’s it.” Then, much to my amazement, I see the Harvard safety taunting Connor, who is writhing on the ground, grabbing his hand. The ref saw it also. Out comes the flag. He announces, “Personal foul. Defense. Automatic first down.”

3. Quinn Epperly ’15 replaces Michelsen. Quinn is left-handed. Harvard is baffled and vulnerable. Epperly marches the Tigers down the field, rolls left and floats the winning touchdown pass to Roman Wilson ’14 with 13 ticks on the clock left. My wife and I are jumping up and down. The tears of joy were running down our faces as we sang “Old Nassau.”

Best. Game. Ever.

Gordon H. Hart ’70

6 Years AgoTriple Overtime Against Harvard

The most memorable game was vs. Harvard six years ago played at Harvard Stadium. Princeton won in triple overtime with the final score something like 51-48. My memory may not be perfect here, but the game was memorable.

Andrew Hauser ’10

6 Years AgoClinching a Bonfire

As a former player, there are many Princeton football games that I’ll never forget (until the CTE sets in, but I digress). On Nov. 11, 2006, we traveled to face Yale at the Yale Bowl in a matchup that would likely determine that year’s Ivy League champion. Just a freshman, I watched as we fell behind 28–14 at the half. I entered the game after halftime due to injuries as our team rallied behind Jeff Terrell ’07 and Brendan Circle ’08 for a 34–31 victory. That day marked many firsts: my first collegiate football snaps, clinching the first Princeton football bonfire since 1994, and the first time I’ve seen visiting fans storm the home team’s field. What an incredible day and memory that I’ll have with me forever.

Neil Shipley ’83

6 Years AgoA Halftime Caper

Not because of what happened on the field, but what happened at halftime ...

I and 11 other members of the Class of 1983 were living in Wilson College in the infamous "Zoo" dorm room: 12 freshmen and two floors of pizza, beer, and a giant cool tiger painting on the wall. A perfect recipe for mischief.

That season before the home game against Yale, we decided we needed to steal the Yale flag from the tower above Palmer Stadium.

In an elaborate and, as it turned out, relatively well-planned scheme, one group faked a run up the tower with the Princeton flag, drawing the attention of the proctors. While their attention was diverted, the real caper was successfully pulled off -- the rest of the team climbed upon shoulders and one of us scaled the Yale tower, pulled down their flag in front of the whole stadium, and threw it down to to my waiting arms.

As the proctors closed in, I in turn tossed it over the edge of the stadium down to my fellow Zoomate, who scampered away with the flag for good.

The stolen Yale flag spent the rest of the year hanging in the Zoo and was given to the one who had actually climbed the tower in honor of his bravery.

Zoomates (who may or may not have also participated):

John Rafter '83

Steven Silverman '83

Mark O'Brien '83

Phil Buri '83

Rick Lipkin '83

Jonathan Intner '84

Gary Jenkins '83

Byron Joyner '83

Yiu-Wai Cheung '83

Eric Pai '83

Mark Blake '83

Robert E. (Bob) Buntrock *67

6 Years Ago'Like a Well-Oiled Machine'

Two chemists and their wives came to Princeton for grad school in chemistry after graduating from the University of Minnesota. Of course we had football season tickets, but were a little disappointed with the '62 team which finished 5-4. Coming from a season where the Golden Gophers were Big 10 and national champs and went to the Rose Bowl, Tiger and Ivy League football were a letdown. The players were “normal” in size and seemed to get tackled too easily.

However, the substitution rules were relaxed in '63, and two-platoon football reigned. Coach Colman declared the best athletes would be on defense and the offense would have to take care of itself. Two guards like Stas and his partner became excellent linebackers, and a trio of tailbacks made the offense purr. I never played football (only touch in the park), but my high school played single-wing and I appreciated watching those Tiger teams in the '60s.

I love running football, and the Tiger teams were like a well-oiled machine with those battering end sweeps. No particular games stand out, but the experience was great. We really missed it when I got my Ph.D., and we moved away and never managed to duplicate the experiences.

Lynn A. Parry ’53

6 Years AgoIn a Hurricane

Dartmouth game in a hurricane in 1951!

Josh Libresco ’76

6 Years AgoHearing the News a Day Later

My most memorable Princeton football game is the same as a lot of people’s most memorable game — the last-minute victory over undefeated Yale on Nov. 14, 1981. The twist for me is that I was not even at the game.

I spent the weekend visiting a friend in Syracuse, N.Y., and we were at the Syracuse/Boston College football game, as the Princeton/Yale game was going on. No internet in those days, but the Syracuse announcer did report scores from other games every once in a while. Early on, he announced Yale 7, Princeton 0. Then later, Yale 14, Princeton 0. Then Yale 21, Princeton 0. As it happened, that was the last time he mentioned the Princeton/Yale score that day. By then, there were lots of other games going on around the country among nationally ranked teams, so the announcer did not spend a lot of time on Ivy League scores.

Even so, whenever various scores were announced, the helpful friends I was sitting with chimed in with Yale 49, Princeton 0; Yale 72, Princeton 0, or other outlandish results that seemed to fit the trend. I never did hear the final score, but I assumed (as did my Syracuse friends) that it had not been a good day for Princeton.

I did not happen to catch the final score that evening or the next morning. Late on Sunday afternoon, as I was driving south on the Taconic Parkway, the CBS radio people reviewed the weekend football scores: “And in a big upset from Princeton, New Jersey, the Princeton Tigers 35, the Yale Bulldogs 31.” I yelled in my empty car and practically drove off the road. No one to talk to — no cellphones in those days, either — but I sang Princeton fight songs all the way home.

Ron Grossman ’67

6 Years AgoA Game of Storybook Proportions

In 1966 Harvard came to Palmer Stadium undefeated and a three-touchdown favorite. It was a game of classic and storybook proportions (think Chip Hilton novels by Clair Bee). Hard-hitting, grind it out — a game traditionalists love.

Five times teams went for broke on fourth down. Harvard threatened to blow the game open, only to have Larry Stupski ’67 throw the Harvard quarterback for consecutive losses and have Jim Kokoskie ’67 intercept the next pass. It led to a 93-yard drive by the Tigers, starting with second-string quarterback Tad Howard ’67 saying in the huddle on their own 7-yard line, “We are going 93 yards for a touchdown and if you don’t believe that, go to the bench now!” Hard running by Dave Martin ’67 and Rich Bracken ’69 provided that touchdown.

The players on the sideline convinced Coach Dick Colman after the touchdown to go for two on the extra-point try, Doug James ’67 to John Bowers ’67 in the back of the end zone. Princeton captain Walt Kozumbo ’67 and James stopped Harvard on 4th and 2 at the Princeton 18-yard line to seal the win. Uncommon resolve and incredible good fortune: Coach Colman called it his most thrilling game since Princeton upset Penn in 1946.

David L. McLellan ’74

6 Years Ago1981: Princeton Defeats Yale, 34-31

Without question, the most exciting football game I’ve ever seen was the 1981 Princeton-Yale game in Palmer Stadium.

Princeton had gone 14 years without a gridiron victory over its historic rival. Yale was undefeated, coached by the almost mythical Carm Cozza, and had (another) All-American running back in Rich Diana, who was amassing more than 100 yards a game.

Princeton had had only partial success during its season, but had some offensive weapons in quarterback Bob Holly ’82 and two or three capable receivers.

Against Yale, Princeton fell behind in the first half by 21 points. A few faint-hearted Princetonians among the 25,000 in attendance headed out.

As the game wore on, Holly and his receivers became stronger and stronger. Magic seemed in play as they caught pass after pass, converted on third downs, and gamely took the field when Princeton’s defense held down the score, even if failing to contain Diana, God of the Tiger Hunt, who ran for 222 yards.

But Holly was unstoppable. With less than a minute remaining, Yale drew a pass-interference call, and the ball was spotted at Yale’s 4-yard line. Four seconds remained as the Tiger runner “crashed through that line o’ blue” ... to dump the Bulldog!

What an explosion from the Princeton fans — an ocean of white hankies to “salute” the “guests” and send them packing: Princeton 34, Guests 31.

In my memory, Air Holly’s feat of 501 yards passing in that game is still a Princeton record. And I’ve carried my 1981 game program (with yellowing newspaper clippings) to every football game I’ve attended since.

Paul Hauge ’80

6 Years AgoA Bolt Out of the Blue

My most memorable Princeton football game is one I did not even attend — or see. I was in grad school in 1981, and I am not sure how I followed the game in those pre-internet days, but I still recall the drama of Bob Holly ’82 leading the Tigers to a last-minute win over Yale at Palmer Stadium, breaking a 14-game losing streak to the Bulldogs. Holly threw for 501 yards (278 of them to Derek Graham ’85) and scored the winning touchdown with four seconds left on a roll-out to the left. In my mind's eye, Holly’s game-winner always plays in slow motion, until a cathartic release when he crosses the goal line.

The team was not exactly a powerhouse during my undergraduate years (combined record of 12-22-2) — I remember an awful lot of handoffs up the middle to Bobby Isom ’78 and Chris Crissy ’81 — so the upset of Yale was like a bolt out of the blue.

John B. Canning ’65

6 Years AgoA Memorable (Blind) Date

The Princeton football game I remember most is the Yale game in 1962, not because of any outstanding plays (although Princeton won) but because my blind date for the game was a young lady from Smith College whom I wound up marrying and to whom I’ve now been married for 51 years!

Sherman Mullin ’57

6 Years AgoWhy I Applied to Princeton

As a high school senior in 1951 football season, I worked as an usher at the Yale Bowl. On Nov. 15 I watched Dick Kazmaier and his Princeton team mates defeat a fine Yale team, 27 to 21. On the spot I decided I wanted to go to Princeton and soon initiated action to apply. Another factor was my strong desire to depart New Haven and the Yalies.

Ken Ackerman ’53

6 Years AgoAn Unforgettable Game — and Lecture

The most unusual football game I ever saw was Princeton v. Dartmouth, the last game of the 1951 season. Dick Kazmaier ’52 had earned the Heisman Trophy and had been on the cover of Time (sometimes considered to be a bad omen). Friday evening, Dartmouth fans boasted that Kazmaier would never finish the game. Football helmets had no nose guards then, and in the middle of the game Kazmaier was out with a broken nose. A few plays later a Dartmouth player suffered a broken leg. It was no longer a football game, it was a vendetta.

One of our professors was psychologist Hadley Cantril, a nationally known Dartmouth alum, and I sat in his 8 a.m. lecture two days later. His opener was something like this:

“Gentlemen” (no women at PU then):

“There was a football game last Saturday. In fact, there were three games. There was the game that Princeton fans saw. There was the game that Dartmouth fans saw. Then there was the real game.

“These three games did not even resemble each other.”

Cantril then used psychology theory to demonstrate how most of us see what we want to see, and are blind to what we don’t wish to see. I will never forget the game (Princeton won, 13–0), or the lecture. They deserve to be preserved in the history of Princeton football.