Bob Ramsay ’72 Says It’s Okay to Start Over

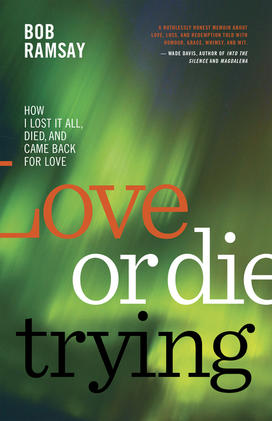

The book: At age 40, Bob Ramsay ’72 was living in a drug treatment center in Atlanta, Georgia. Love or Die Trying: How I Lost It All, Died, and Came Back for Love (Dundurn Press) tells the story of what happened next: his winding journey of recovery, love, tragedy, and resilience. Ramsay shares how he married an older woman, Jean, and began a life of adventure that gave him a second chance at happiness — until the day his heart stopped. Against all odds, he survived again, and memoir Love or Die Trying reflects on the themes of perseverance, mortality, and love that have defined Ramsay’s life.

The author: Bob Ramsay ’72 is the president of Ramsay Inc., a Toronto-based communications and marketing firm. Born in Edmonton, Canada, he graduated from Princeton with a bachelor’s degree in English, and built a career in advertising, speechwriting, and opinion writing. He runs a blog, RamsayWrites, and has operated a speaker series called RamsayTalks for 30 years.

Opening lines:

It’s said that 90 percent of interventions led by friends or family members fail, while 90 percent of those led by a professional interventionist succeed. By succeed, I don’t mean that the person being intervened on stops drinking or doing drugs for the rest of their lives; I mean they take the first step to getting help to stop. This usually means attending meetings of Alcoholics Anonymous or its many variants, or agreeing to go to treatment in a rehabilitation facility.

In my case, there was no time to find a professional, and I was too far down the hole of my addiction to give stopping more than a frantic passing thought.

My best friend Charles Fremes was worried about me. A month earlier, I’d had to borrow money from him to take a train home after a wedding in Montreal.

My accountant, Arthur Gelgoot, had warned me, “Just don’t get arrested.” My denial was so tight that I was offended by Arthur’s words. How did he know? How dare he think I’d run afoul of the law?

Of course, as with most alcoholics and addicts, everyone knew. Why did my staff of ten all drift into jobs elsewhere? They knew. Why was I huddling in a tiny office that I’d bargained for with my landlord after giving up our entire floor upstairs? She knew. Why were the tenants in my triplex dropping their cheques in my mailbox and not ringing the doorbell to chat? They knew.

As for the police, it’s a miracle they didn’t pull me over as I inched my way home in my car, terrified of exceeding the thirty kilometre per hour speed limit, and instead driving only twenty.

Addiction is a way to push people away.

But Charles and Arthur hung in there. Once, many months after they engineered my intervention, Charles said to me, “You grossly underestimate the depth of our friendship if you think you can run away from me — and us.”

Charles and Arthur were also well aware that I’d never sit still for an intervention. So, Charles called me one night. “Arthur and I want to meet with you to do some long-term business planning. How about tomorrow afternoon?”

I was flattered. Long-range business planning implied a number of things that were no longer true: that I had a business, that I was able to plan anything beyond my next high, and that my long-range future looked even possible.

At some level, I knew this was the intervention that I’d both dreaded and desperately hoped for. That’s the thing about addiction: a rare glimpse of reality will occasionally seep through the tightly held denial. It’s in those brief moments that change can happen.

All the next morning, I was tempted to call my friends and cancel. But I was just so tired and lonely, and so hurt that my willpower could do nothing to help me stop. So, I waited for the knock on my office door at 2:00 p.m. The door was locked, of course, because that’s what addicts do.

When they arrived, Charles kept the mood light, just like old times, with lots of witty chit-chat. Then he pulled out a piece of paper. “Arthur and I have done up an agenda for our meeting so we can use our time efficiently.”

Again, I was flattered. This sounded like I just had to do a little planning and everything would soon be shipshape.

He handed me the paper. There were half a dozen items on it — “Clients,” “Staffing,” “Taxes” — but item number one was “Improving Your Health.”

“So we need to talk about your health first,” Arthur began, “because if you’re not prepared to work on that, then there’s really nothing to say about the other items.”

“My health?” I asked.

They were tired of my denial. “Your cocaine addiction.”

“Right. Yes, of course.”

“You need to give yourself a break. We think you need to go away to get better ... We’ve found a place for you —”

“Really?” I was so grateful I almost broke down in tears. This hell would soon end. I could start over. They cared! Charles and Arthur were the cavalry, and the cavalry had finally come to rescue me.

“It’s a treatment centre outside Atlanta.”

“Atlanta? Why so far away? I can’t go there. I’ve got things to do here.” My denial was preventing me from grasping the lifeline they had thrown me.

“Like what?” asked Charles.

“Well ... like ...” Actually, there wasn’t a single thing I could think of that was holding me back from seeking treatment. I had no kids, no work, no relationship, and I was fast pushing away my few remaining friends.

Arthur stepped in. “Don’t worry, we’ll pay the bills when you’re gone.”

But I was terrified that people would find out, and worse, talk.

Again, as I would learn when I intervened on dozens of others in the thirty years since then, we addicts have a huge fear, not just that someone will learn our secret, but that they’ll tell others about it.

Somehow, Charles and Arthur, who’d never intervened on anyone in their lives, got this part right, too.

“You can just tell people you’re taking a creative break in Banff, maybe doing some courses at the Banff School.”

That was perfect. I’m from Alberta, and had taken summer courses in Banff when I was a teen. So, I had a cover story.

“What’s the treatment centre?” I asked.

“It’s called Talbott Recovery Center. We’ve checked it out for you and they have a space open. They can take you tomorrow. I’ll fly down with you. There’s an 8:00 a.m. flight.”

Whoa ... whoa ... The twin panics of getting well and being deprived of my drug took over.

“Tomorrow?”

“Sure, why not?”

“Because I’ve got lots to do!”

“Like what?”

“Like ...”

Of course I had nothing to do.

“You have a passport?”

“Yes.”

“Good,” said Arthur. “I’ll pick you up at five thirty tomorrow morning at your house. Meanwhile, you’ll need to call the people at Talbott. We talked to them yesterday, but they need to hear from you directly that you want to come. They won’t take you unless you call them.”

They made it sound like a marvellous adventure, which is another reason I said the words every interventionist prays for: “Yes, I’ll go.”

I was so incredibly relieved the pain would soon end that I forgot to push them about why Atlanta instead of someplace in Toronto. I later learned that I was headed to Talbott because, earlier that week, Charles had called his father, a doctor who vaguely knew me through his son, and asked him which was the best treatment centre for me in Toronto.

What Dr. Fremes said next may well have saved my life: “You don’t want to send him to Bellwood or Homewood or Donwood. He’ll just charm his way through them and come out thirty days later just as addicted. From what you say, Bob Ramsay needs long-term treatment. You should send him to where we send the doctors.”

The entire intervention took no longer than fifteen minutes, and as he walked out the door, Arthur pointed his finger at me. “Call them.”

I did call, but it took me a few hours to build up my courage — and I was stoned when I dialed the phone. The very minute my friends left, I wrote a company cheque to “Cash,” signed it, and took it to my cocaine dealer, who gave me three grams of coke. I wasn’t sure I had the money to cover that $450, but I knew that banks didn’t bounce cheques made out to Cash.

Ah, the cunning of the not so innocent.

And the iron grip of addiction.

Reprinted from Love or Die Trying: How I Lost It All, Died, and Came Back for Love, by Bob Ramsay. Copyright 2021 © Dundurn Press.

Review:

“A ruthlessly honest memoir of love, loss, and redemption told with humour, grace, whimsy, and wit.” — Wade Davis, author of Passage of Darkness

No responses yet