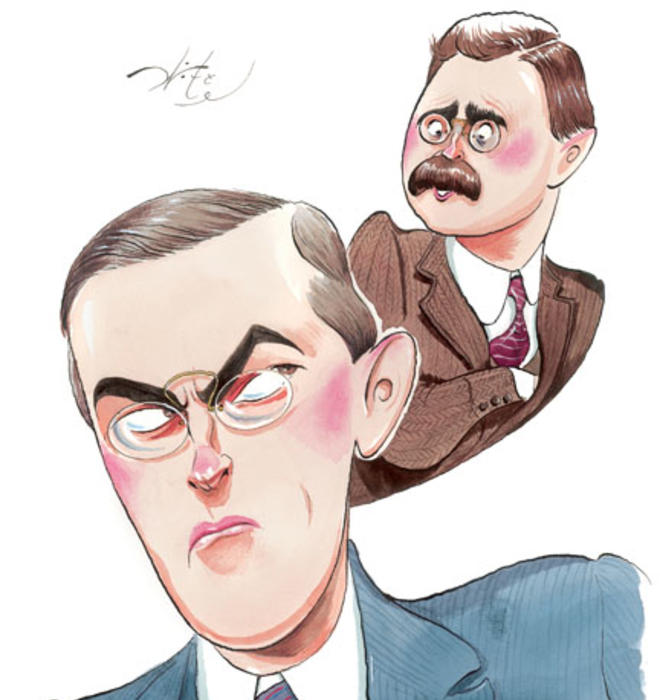

The Brutus of the conspiracy

Woodrow Wilson and John Grier Hibben each won Princeton’s presidency, but a bitter dispute over the University’s future destroyed their friendship

As president of Princeton, Woodrow Wilson 1879 became one of the most revered educators in America — and one of the most hated. In a new book, W. Barksdale Maynard ’88 tells the story of Wilson’s complex relationship with Old Nassau from freshman year to the day he died. This excerpt describes the falling-out between Wilson and University president John Grier Hibben 1882 — best friends turned bitter foes in a clash Wilson’s daughter called the most painful of his life. Here we see one of Wilson’s most infamous and perplexing characteristics: his vindictive streak. (Adapted from by W. Barksdale Maynard, Yale University Press, 2008. Reproduced by permission.)

Young Jack Hibben and Woodrow Wilson had much in common: Presbyterian ministers’ sons, Whig Hall orators, avid football fans — although dapper Hibben, a native of Peoria, lacked Wilson’s inner fire. “Idealism and pragmatism thus in company,” one professor thought when seeing them walking together as undergraduates. Their relationship blossomed when both were on the faculty; their wives, Ellen Wilson and Jenny Hibben, grew close, too. The Hibbens’ affection “so brightened and strengthened our lives in dear old Princeton,” Woodrow told Jenny.

Wilson was never so happy as when spending Sunday afternoons with these friends, chatting about literature over tea or taking walks down quiet sidewalks lined with wrought-iron fences tangled with yellow roses. The Hibbens were far more stylish than the Wilsons, who dressed frugally and whose social life typically consisted of staying home to read Wordsworth around the hearth. A friend later recalled how the Hibbens always were trying to “run the Wilsons,” pushing them to dress better and mingle with the influential, wealthy families of the town, the Moses Taylor Pynes and Grover Clevelands. Jack Hibben was building social connections that would serve him well throughout his career. He worried that his friend Woodrow was not.

Once Wilson became president of Princeton, he depended more than ever on Hibben. “Wilson’s alter ego,” Ellen’s brother, Stockton Axson, called him. In 1907, Wilson announced his quad plan, the culmination of years of thinking about educational reform and “Princeton in the Nation’s Service.” It would create four-year, community-building residential colleges and shut down once and for all what Wilson saw as the snobbish eating clubs of Prospect Avenue. Club-haunting alumni were livid, and Jack Hibben became uncharacteristically cold. “He wants me to give up my plan for the quads,” Wilson told his family as Hibben announced he was coming to see him, interrupting the family’s Adirondacks vacation. As Hibben stepped off the carriage, Ellen’s sister Madge Axson wondered to herself, “Why, why are you doing this?”

“If he [Wilson] persists now, he will split Princeton in two,” Hibben told the family. “I want to save him and Princeton.” But Ellen was furious at his disloyalty. As he left, she lashed out, accusing him of wounding her husband and disheartening him for the fight — Hibben had “robbed him of hope.”

Hardly anyone in Hibben’s circle of influential Princeton friends thought quads were sensible. Pyne, a trustee, had been talked out of them when he saw how angry the clubmen were, and Andrew Fleming West 1874, dean of the Graduate College, convinced trustee Grover Cleveland and others that quads were useless. West felt personally betrayed: He had turned down an offer to head M.I.T. when Wilson promised him and Cleveland that the Graduate College was the next, top priority of the University. Opposition at so high a level never could be overcome, Hibben knew. Ordinarily “I would have gladly stood with you shoulder to shoulder against the world,” he told his friend. But now Wilson stood alone in defense of a foolish, pet scheme.

Back home, Hibben telephoned young New York mayor George McClellan 1886, saying he urgently needed advice. A faculty vote was coming up, and Wilson had assured him he was free to follow his conscience. “You don’t suppose that Woodrow would tell me to vote according to my convictions and not mean it, do you?”

McClellan astonished him with his reply. If he voted against Wilson, McClellan warned, “He will never forgive you.”

Tanned and reinvigorated, Wilson returned to Princeton to face the faculty in Nassau Hall in late September, expecting an endorsement of the quad plan from the men who recently had approved his preceptorial system wholeheartedly. But battle lines were drawn when Professor Henry van Dyke 1873 offered a counter-resolution that opposed quads. And who should rise to second it but Jack Hibben! The room was frozen in stupefied silence. Sancho Panza might as well have stood up against his beloved Don Quixote. “The president’s look of shocked amazement was rather terrible,” an eyewitness reported. Another remembered the tightening of the muscles of Wilson’s long jaw, the pallor spreading over his face, as he said, “Do I understand that Professor Hibben seconds Professor van Dyke’s motion?”

“I do, Mr. President.”

At this decisive moment in the history of Princeton and of American higher education, with Wilson’s dreams at stake, his best friend suddenly had betrayed him. His vision would have to wait — a very long time. That fateful faculty meeting took place Sept. 26, 1907: 100 years and a day before the dedication of Whitman College, when Princeton finally tried a version of the quad plan.

“He might have let someone else second the motion!” exclaimed Madge Axson as she burst into tears on hearing what Hibben had done. Ellen Wilson told her daughter that the counter-resolution was insulting and “virtually a vote of want of confidence” in Woodrow. Van Dyke read it “in a manner that was the most studied insult in itself, and then Mr. Hibben seconded it! People could hardly believe their eyes or their ears.” Ellen tried to comprehend Hibben’s wickedness. “Of course he has (being very slow and stupid) been made a tool of by those malignants, van Dyke and West, and does not realize what he has done. ... Mr. Hibben is called the ‘Brutus’ of the conspiracy, and everyone says his influence and prestige in the faculty are gone forever.”

But far from being wounded, Hibben had cemented his position with the Pyne camp, which proved shrewd. He believed he was working for peace and the financial security of Princeton — not to mention his own security. The price was his friendship with Woodrow Wilson, whose star was fast declining. With Pyne’s support — and to the horror of the Wilsons — Hibben would be appointed University president in 1912, after Wilson had resigned to become governor of New Jersey.

A glimpse into secretive Hibben’s mind-set would come years later, in an interview with Wilson biographer Ray Stannard Baker. “A conciliatory man, with the marks of worry between his eyes” was how Baker found Hibben on the porch at Prospect House in June 1925. “It is plain that he still feels the old wounds of the broken friendship. ... He spoke several times of its being a painful story.” But Hibben offered few details, fearing further embarrassment to himself and to Princeton. (Covering his tracks, Hibben later would burn his personal papers.) “He is a timid man, extremely anxious in regard to his own record,” Baker concluded. “He wishes to give the appearance of frankness without being frank. ... He says that he never had an open break with Wilson, that no bitter words or bitter correspondence ever passed between them — that the friendship upon Mr. Wilson’s part simply stopped.” †

Some thought the friendship had been odd from the beginning — including Sigmund Freud, who once wrote that Wilson mistook himself for Jesus, with Hibben playing Judas. “We could not understand why he put so much trust in Hibben, who was distinctly a second-rate man,” Professor Charles McIlwain 1874 remembered. “Hibben was a poor teacher — very poor, a bonehead — but was popular with the undergraduates.” After Hibben’s betrayal, Wilson found him to be, as he wrote to a friend, “hopelessly weak and utterly in love with what would ruin the place — viz. the Pyne-West standards and ideals.” And so he cut out the traitor forever.

But Hibben proved hard to avoid. In the middle of Wilson’s campaigning for U.S. president in May 1912 came an invitation to speak at Hibben’s inaugural as president of Princeton, a horrid task. “I cannot say what I really think without causing a riot,” an anguished Wilson told his family. He declined, with the excuse that he had an engagement elsewhere. Then he made plans to leave town, though he felt guilty at shirking his responsibilities as a member of the Board of Trustees (an honorary role accorded governors of the state). As so often in his life, he was torn between politeness and truth, peace and duty. “To be present and silent would be deeply hypocritical; to go and speak my real thoughts and judgments would be to break up the meeting and create a national scandal, to the great injury of the dear old place. No doubt I should stay away. But it is hard and it is mortifying. To be true to oneself and candid in the utterance of the truth is to live in a very embarrassing world. And yet what man would buy peace at the price of his soul?”

June 1914 brought the Class of 1879’s 35th reunion. Wilson wanted to go, but he could not bear to see Hibben. Seeking reconciliation, Hibben asked one of Wilson’s classmates to convince him to attend a reception at Prospect House after the baseball game, but Wilson said no, making the excuse that he wanted it “to be absolutely ignored that I am president of the United States.” He would be in Princeton on Saturday from noon until midnight and, by careful planning, was to be protected and insulated the whole time by a loyal phalanx of ’79. †

Five hundred excited students thronged below Blair Arch to greet him a little after noon on June 13. Stepping out of the train car into the sunshine, Wilson wore the class uniform of dark blue sack coat, white trousers, white shoes. He smiled broadly as locomotive cheers went up for “Wilson, Wilson, Wilson”; then he doffed his hat at the yell for ’79. How refreshing it was to be called “Woodrow” again! If anyone could unwind him it would be his classmates — the only people, his sister-in-law thought, who had ever dared slap him on the back.

Two automobiles were waiting, but Wilson preferred to walk. He strode up Blair steps, the crowd falling in behind. Right by his old window in Witherspoon Hall they marched, then down the leaf-dappled shade of McCosh Walk. As he entered the shadowy, brick-groined archway of Seventy-Nine Hall, a band struck up “Hail to the Chief.” President Hibben walked over from Prospect and had to be greeted, but quickly the schedule called for a private class lunch in the Tower Room upstairs, briefly interrupted by a telephone call from Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan. †

Wilson and the Class of 1879 assembled behind Nassau Hall for the P-rade to University Field, where the president took his seat in the west stands to deafening cheers from the crowd of 12,700. Winding its way around the sunny track, the P-rade was colorful as always: The Class of 1904 wore kilts, and members of 1907, dressed as Arabs, were accompanied by a camel. Ninety-four allowed wives and daughters to march, which scandalized many alumni, one wondering if this was “the first insidious step (God forbid!) towards turning Princeton into a co-educational institution.” ††† †

Some classmates grumbled when the group picture on the steps of Seventy-Nine Hall had to be postponed, as Wilson, overcome by exhaustion and the secret strain of seeing old foes, said he needed a nap. Dinner was served at 7 in the Tower Room, heavy tables arrayed in front of the huge stone fireplace, the noise of talk and laughter echoing off the brown oak beams of the lofty ceiling. During the meal, Wilson forgot for a few minutes his worries about world affairs and Ellen’s declining health. He was given a gift, a small-scale replica of one of the class’s bronze tiger statues in front of Nassau Hall. Then the conviviality gave way to hushed silence as the president of the United States rose to speak.

He would not make a formal speech to them, he said, for “I cannot put up a bluff before you fellows.” And bluff he did not, instead lashing out at old adversaries. “There are some pretty grim things I have learned in life. For one thing, I hope never again to be fool enough to make believe that a man is my friend who I know to be my enemy. ... We ought not to deceive ourselves. Men are tested. They do make their records. Their records are to be read. If a man has proved himself a coward, he is a coward. If he has proved himself unfaithful, he is unfaithful; and in performing public duties you should not associate yourself with him.” It was an obvious reference to Hibben.

Never before had Wilson unburdened himself so frankly in public, but he felt that he was among trusted friends. These were companions he had known in his innocent youth, before he could have imagined anyone could betray him, when “we opened our hearts and minds to everybody.” But now he was wiser. In the P-rade “I knew the sheep from the goats. ... They always were goats; they are goats now; and I will not make any predictions except to remind you that there will be an arrangement for goats in the next world.”

He spoke as if to buddies, but his candor stunned and infuriated many in the room that night who were longtime associates of certain “goats.” Already they were embarrassed at how Wilson had refused to shake the hand of a trustee classmate who helped elect Hibben president. “Well, Billy, I guess we’re goats,” Robert McCarter said in exasperation to Professor William Magie. In Magie’s opinion, “The class wouldn’t have voted for Wilson for poundmaster at the end of that evening.” And he had not even thanked them for the tiger.

With a heavy heart and a wearing a black armband in mourning for Ellen, who had died of Bright’s disease, Wilson returned to Princeton that autumn to vote, accompanied by Madge and Stockton Axson. The world was at war now. Surprisingly, few paid them attention as they walked out to see the nearly finished Palmer Stadium, then through their old neighborhood. At the train depot, a dramatic episode unfolded. Woodrow Wilson stood talking to friends when Jack Hibben rushed up, breathless. “Mr. President, one of the students told me that you were asking for me,” he said eagerly. Here at last, Hibben thought, was the reconciliation he had longed for and a belated blessing on his Princeton administration from the president of the United States.

Madge saw instantly what had happened: a student prank. Perfectly courteous and unbelievably remote, Wilson said only one word: “No.”

W. Barksdale Maynard ’88 is a lecturer in the School of Architecture.

2 Responses

Robert R. Cullinane ’70

10 Years AgoNot-so-foolish idea

Edward F. Duffy

10 Years AgoVindictive, or wounded?

In “The Brutus of the Conspiracy” (feature, Sept. 24), W. Barksdale Maynard ’88 chronicles the sad demise of the close friendship between two of Princeton University’s former presidents, Woodrow Wilson 1879 and John Grier Hibben 1882. He points largely to the undeniably dramatic moment of “betrayal” — namely, the faculty meeting in which Hibben took Wilson by surprise by “seconding” a motion made by English professor Henry Van Dyke, in opposition to the Quad Plan, as presented by Wilson. Further, Maynard showcases what he calls a “vindictive streak” in Wilson.

Interestingly, however, after Wilson was elected president of the United States, his appointment as ambassador to the Netherlands was none other than the maker of the “anti-quad plan” motion, Henry Van Dyke — a fact not mentioned in Maynard’s article. Was Wilson solely and simply vindictive in his future relations with Hibben? Can the situation fairly be cast in such dramatic terms, or dare we say, as Ellen Wilson (the first lady) was to say, her husband quite simply was “wounded”?