Canvassers Go Door to Door, Tracking Sentiment in the Arab World

Arab Barometer is a joint venture headed by Princeton, the University of Michigan, and three institutions in the Middle East

The canvassing team was having a bad night. On a warm evening in February, they had knocked on door after door in an upper-middle-class neighborhood of Kuwait City and struck out every time.

Working in teams of two or three, about 20 people were collecting survey data for the Arab Barometer, a joint venture headed by Princeton in collaboration with the University of Michigan and three institutions in the Middle East. It is the longest running and largest repository of public opinion data in the region, encompassing 15 countries from Morocco to Yemen. Hospitality is strong in the Arab world, so doors aren’t usually slammed in a canvasser’s face, but residents still had ready excuses for saying no: “It’s late,” “we’re eating,” “we’re putting the kids to bed.”

Completing the survey, which is always done in person, is a big undertaking. If a canvasser is invited in, a subject agrees to answer more than 200 questions on topics ranging from their work history to their views on democracy, the economy, and foreign affairs. Even for an experienced interviewer, it can take nearly an hour. Political pollsters in the United States have found it increasingly hard to get people to answer surveys, but response rates remain high in the Middle East, says Amaney Jamal, dean of the School of Public and International Affairs and one of the Arab Barometer’s founders. On a good night, she says, canvassers can get an 80% response rate.

“Remember, these are countries that are primarily authoritarian, so when you knock on someone’s door and say ‘your opinion really matters, we really care about what you have to say,’ they’ll respond,” Jamal says.

In Kuwait, which is more politically open than many countries in the region, canvassers knocked on 4,796 doors over a monthlong period and conducted 1,210 interviews. To boost their credibility, everyone on the team wore matching gray vests and baseball caps bearing the logo of Kuwait University’s Center for the Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies, a local partner for the project. They had also obtained a letter from the police vouching for their legitimacy. The goal was to get at least 10 responses in this neighborhood, but the canvasser on this particular street had gone 0-for-19.

A woman drove up in a Chinese-made Changan sedan and parked outside her apartment complex. Dressed in jeans and a sweater and wearing a hijab, she eyed the canvassers a little warily as she collected groceries from the back seat. Marwan Khraisat, a researcher at Saudi Arabia’s King Saud University who was supervising, approached her, explained what they were doing, and asked if she would participate.

“Why does the government want our opinion? They already know it,” she asked in Arabic, as Khraisat translated her response. He explained that the canvassers were not government employees. After asking a few more questions, she agreed to consult her husband, disappearing up a flight of steps. Fifteen minutes later, it became clear that neither she nor her husband was coming back down. The canvassers moved on.

“Remember, these are countries that are primarily authoritarian, so when you knock on someone’s door and say ‘your opinion really matters, we really care about what you have to say,’ they’ll respond.”

— Amaney Jamal

Dean of the School of Public and International Affairs and one of the Arab Barometer’s founders

Jamal first conceived of the Arab Barometer when she was a doctoral student at Michigan during the late 1990s and early 2000s. Political scientists could survey public opinion in countries around the world, she observed, but not the Middle East. “People were assigning this monolithic Arab street narrative,” Jamal recalls. “I would say to colleagues, we need an accurate source of data.” After 9/11, that lack of insight on what ordinary citizens in the region thought about the world suddenly became acute. With funding from the U.S.-Middle East Partnership Initiative, the first set of Arab Barometer surveys were conducted in 2006. They are now completing their eighth wave of reports.

Although the Arab Barometer tries to partner with a university in each country they survey, canvassers are recruited from around the region. Those working in Kuwait this year received several hours of training from Ghanim Al-Najjar, the founder of Kuwait University’s Center for Strategic and Future Studies, and Samir Abu-Rumman, managing director of the Gulf Opinions Center for Polls and Statistics and a visiting politics professor at Princeton, who emphasized the importance of careful data collection and explained how their findings would be used. Survey responses were recorded on electronic tablets and uploaded each evening to a server in Princeton, says Michael Robbins, a director and co-principal investigator. He and his team at Princeton then sorted and tabulated the data while giving feedback to those in the field.

Reports are issued for each country on a rolling basis. Some countries, such as Iran, are too repressive to allow field work, but canvassers do work in places, such as Yemen and Iraq, that can be dangerous. The Arab Barometer was fortunate to have completed most of its interviews in Gaza and the West Bank by Oct. 6, the day before the Hamas attack on Israel. Their findings, showing that a majority of Gazans were deeply dissatisfied with the Hamas government and supported an independent Palestine existing alongside Israel, were published in Foreign Affairs and widely publicized.

Across the region, though, Jamal and Robbins say that support for the United States has dropped sharply as the war in Gaza has continued. In Kuwait, for example, historically a strong American ally, only 16% of respondents said they had a favorable view of the U.S., as compared with 55% who felt favorably toward China and 49% toward Russia. China, Jamal says, is gaining support across the region at America’s expense.

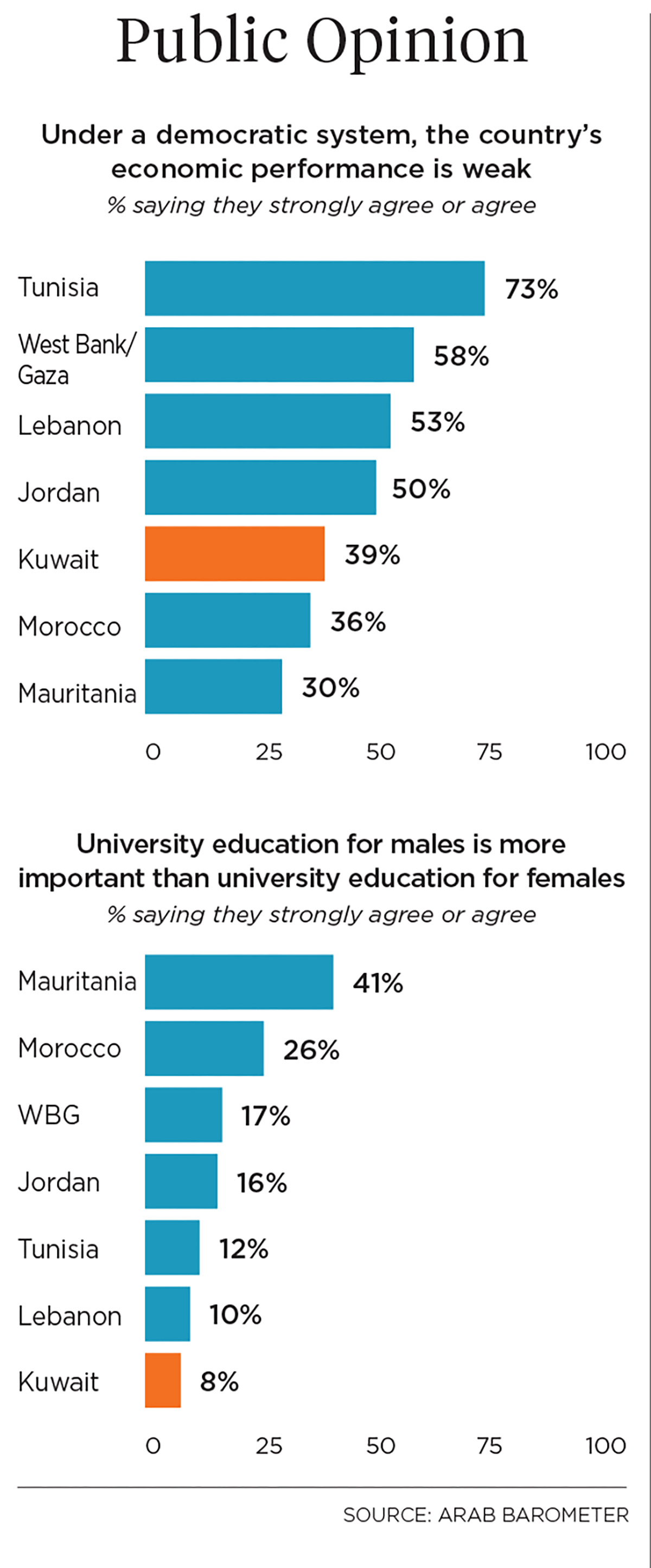

Taking a broader view, Jamal says that support for democracy has declined since the Arab Spring a decade ago, as greater political freedom in Tunisia, Egypt, and elsewhere has not been matched by economic advances. In many parts of the Arab world, the average family may be poorer than it was under more autocratic governments. Jamal sees a message in this for both donors and pro-democracy groups: “If you really care about democracy, you need to make sure that people aren’t paying a huge [economic] price for it.”

Robbins believes that the project provides an invaluable resource for political scientists and policymakers around the globe. “People always said that the Middle East couldn’t be surveyed,” he says. “But I think it has been a huge contribution of the Arab Barometer to show that you can do this and do it reliably. It has helped our understanding of how citizens view their world throughout the region.”

The Arab Barometer’s final report on Kuwait this year was issued in June, so in mid-February, canvassers were still out doing the hard work of collecting data.

Moving on from the apartment complex, Khraisat walked to a different part of the neighborhood to check on canvassers there. Zaina, an Egyptian gym teacher who was canvassing in Kuwait to earn some extra money, had enjoyed better luck. She had knocked on nine doors and completed four interviews.

Reviewing the survey responses on her tablet, Khraisat nodded his head approvingly. They had about an hour left to canvass and still needed more interviews. He and Zaina continued down the block, ready to knock on another door.

No responses yet