Captain Hobart Baker’s Career in the Service

To the many friends of Captain Hobart A. H. Baker '14 the news from France that he was killed in an accident while flying at the Toul aerodrome on Saturday, December 21st, came as a great shock. With the fighting at an end we had all been hoping to see him home before long, where we could personally do him the honor which he so richly deserved, for no one ever knew Hobey Baker who did not admire him for his many splendid qualities and the work he had done, and love him for the man he was. His death makes us realize more than ever that the great war did not end with the signing of the armistice, nor will it end for many years to come, and we know that our friend has laid down his life for a cause to which his whole heart was devoted, just as surely as though he had gone down in combat on the lines.

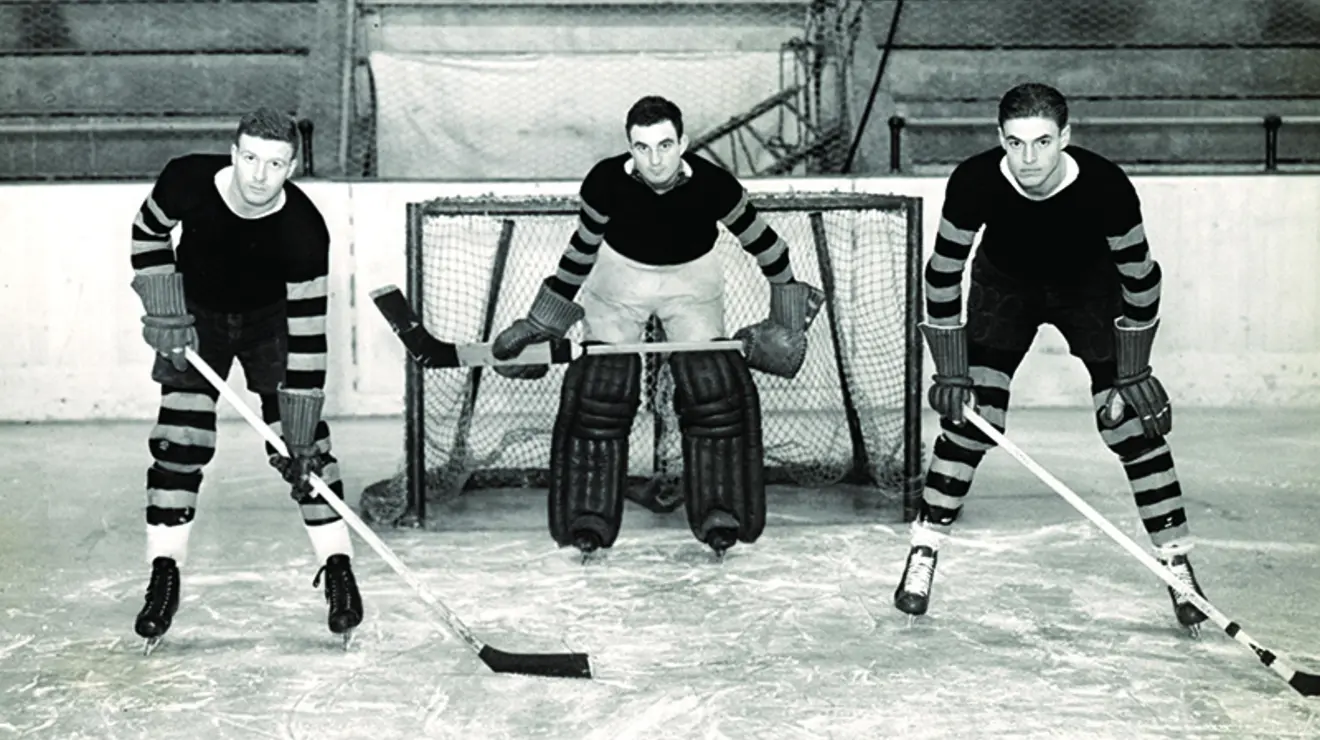

After a long and phenomenal career as an athlete at Princeton, Hobey Baker took up flying more than a year before America's entry into the war, with the idea of fitting himself for the service should the need arise. As might have been expected of probably the best and most successful athlete this country ever produced, he excelled in flying as he had at football and hockey.

Early in the summer of 1917, he went to France as a First Lieutenant among the first of the American pilots, in order to take the advanced courses in acrobatics, combat and gunnery, which could not at that time be obtained in this country. He first took a course at a Flying School in England and then at the French Schools at Avord, Pau and Caz- aux. At the Gunnery School at Cazaux he made a brilliant record. He appreciated the fundamental principle that for the pilot of a pursuit plane to do accurate and effective shooting, he must from the first train himself to fire from the shortest possible ranges. His appreciation of this however almost led to his undoing On one occasion. In diving on a balloon used as a target, Hobey tried to maintain his fire until very close. He riddled the balloon but misjudged his distance and ran into it just as he was pulling away. The impact shattered his propellor and badly strained the machine, and the cloth of the balloon became wrapped around one wing and thereby threw the plane out of balance. Those watching on the ground held their breath a gave him up for lost, give up and realize that in aviation the but Hobey was one of those who never surest way to lose your life is to lose your head. By the most skillful handling of his crippled machine he was able to bring it safely to the ground, to the great delight and astonishment of his French audience.

Lieutenant Baker had hoped to be sent as soon as he had completed his training, but he was assigned to instruction work and kept at this duty for some time. I saw him in Paris in January and he was leaving no stone unturned in trying to get orders which would take him to the front, but there were many unavoidable delays, so that his long hoped for orders did not finally arrive until about the first of April, 1918. He was at this time sent to the 103rd Aero Squadron, better known un- der its old French name as the "Escadrille Lafayette." The pilots of the squadron had already transferred from the French to the American service and the enlisted personnel was almost entirely made up of American mechanics, but the squadron itself was still operating with the French and continued to do so until about the first of July. On April 1st he was with the famous Fourth Army in Champagne under General Gouraud, covering the lines between Rheims and the Argonne Forest, in conjunction with a number of French squadrons. I was myself a flight commander in the Lafayette Squadron at the time and was delighted when Lieutenant Baker was assigned to my flight. An American pursuit squadron is divided. into three flights of six or seven pilots each, and patrols are usually made by flights led by the flight commander. There is nothing so reassuring to a pilot as to know well the men with whom he is flying and to feel that they will stick with him through thick and thin, regardless of odds or the dangers to themselves.

Soon after Lieutenant Baker arrived at the Lafayette Squadron, we moved to Fismes with the Chemin des Dames region as our sector. On April 12th Hobey went out with me for his first flight over the lines. We had hardly gotten started and were still climbing to gain our altitude when I sighted a German two- seated photographic plane coming into our lines high above us. We immediately started in pursuit, but although we got within a thousand yards or so, the Hun was too far above us and got back into his own lines before we could come within range of him. A few minutes later almost the same thing happened again with another two- seater, who caught sight of us and escaped far into his own lines before we could get near him. When the patrol was over and Lieutenant Baker and I were walking to our quarters I said to him, "Well, Hobe, I guess you saw what a Hun looks like, anyhow." To which he replied, "No. Where? I did not see any." Then I told him about the two that we had been after and he was terribly disgusted with himself for not having seen them. As a matter of fact it was the best thing that could have happened. All his friends knew from the beginning that he would make a splendid pilot, but feared that in his great anxiety to fight he would try to begin by doing too much. One of the greatest dangers to a new pilot at the front is that, no matter how great his ability and how hard he may try, he will at first probably not see more than one-third of what he will see after he has had a little experience. The reason for this is that he is occupied with his machine, with keeping his place in the formation, and in trying to learn the country over which he is flying. Then also other planes in the air do not so readily catch his eye as they do that of a more experienced man. The result is that new men run a great risk of being taken by surprise, and an experience such as the above impresses this all important fact upon them as nothing else could. Lieutenant Baker learned the game in a remarkably short time and it was not long before he saw as well as the best of them. In all his experience at the front I do not remember a single instance when he was caught unawares.

About the end of April the Lafayette Squadron moved to Flanders for the battle around Kemmel Hill south of Ypres. Our first flight in this sector was a daylight patrol one misty morning when the French were counter- attacking in the region of the Hill. The mist and low clouds forced us to fly at an altitude of only about two hundred yards and the shelling on the ground was terrific. Kemmel Hill looked like a volcano in eruption, and the shells were falling so thick on its summit that the whole top of the hill seemed to be constantly exploding and resembling somewhat a huge pot of boiling water. In the mist it was very difficult to keep formation and Lieutenant Baker became separated from the rest of the patrol. Soon afterward I caught sight of him in the fog, flying in the direction of the German lines. It was his first flight in this sector and the weather conditions were such as to make it almost impossible for one not familiar with the country to keep his bearings. I had myself spent five months in this region with the French aviation in the summer and fall of 1917, so that I knew the ground. Seeing Lieutenant Baker making off into the Hun lines, I thought he must be lost, so started after him, firing my gun to one side of him to attract his attention, but the noise of his own motor, added to the din on the ground, prevented his hearing me and he disappeared in the mist. Upon returning to our field near Dunkirk we waited anxiously for him to come back, but four or five hours went by without news from him. We were all beginning to be very much worried lest he had gotten lost and either been shot down or forced to land in German territory, when to our great relief and delight a telephone came from an English field near Bethune, saying that he was there and safe. It seems that after becoming separated from the patrol and not knowing the country, Lieutenant Baker had started home by compass, but unfortunately there was something wrong with his compass, so that when it read "west" he was in reality flying south. At this time the lines south of Ypres made a large bulge west towards the forest of Nieppe, and flying south took Lieutenant Baker across this salient. He flew for miles inside the German lines, and each time he would come down out of the mist to see where he was he would be greeted by a burst of fire from the ground. He worked around more to the west and finally when he came down to look once more, he breathed a sigh of relief upon seeing a lot of British Tommies marching along a road. He landed near Bethune after having flown across the entire salient, and a joyful squadron we were to have him safely back with us again.

His First Hun

It was toward the end of May that Lieutenant Baker brought down his first German plane. Five men from the Lafayette Squadron attacked a loose formation of about twenty- five Hun scouts and Lieutenant Baker shot down one of them near Ypres, a very fine performance, considering how greatly our men were outnumbered. For this he was decorated with the French Croix de Guerre, the ceremony taking place at Hondschoote in Belgium on June 12th. Towards the end of May the Hun aviation in Flanders was greatly reduced, most of the squadrons evidently having been moved further south for the offensive there. In consequence opportunities were hard to find and Lieutenant Baker got few chances until the Lafayette Squadron moved to the St. Mihiel sector about July 1st, with head- quarters at the Toul aerodrome. I had just been given command of the 13th Aero Squadron and succeeded in getting Lieutenant Baker transferred to it as a flight commander. He accordingly left the Lafayette and became a member of the 13th about July 15th. But the St. Mihiel front was very quiet at this time, and although Lieutenant Baker spent more time over the lines than any other man in the squadron and was of invaluable service in training the new pilots, he was hardly able to get a shot at a Hun. One two-seater which he attacked went down in a spin for a long distance, but managed to straighten out just before he hit the ground and got back to his own lines.

The first week in August Lieutenant Baker was put in command of the 141st Aero Squadron and was ordered to the rear to complete its organization and bring it to the front. As bad luck would have it, his squadron was not ready and it was not until the end of October that he was finally able to get it in operation on the front, the squadron at this time being made a part of the 4th Pursuit Group, stationed at the Toul aerodrome and flying in the St. Mihiel sector. As was often remarked by his friends, Hobey Baker was from the beginning beset by the hardest kind of luck. Through no fault of his own, or rather in spite of everything he could do, he was held a long time in the rear before getting to the front, then when he got there he had a lot of trouble with his machine guns failing him at critical moments, and finally when he got a squadron of his own, it was one which was not ready for the front while other men who were made squadron commanders after him had the good fortune to get squadrons which were all equip- ped. Then just when Lieutenant Baker had gotten all his pilots and was ready to take them to the front, it so happened offensive, and his men were al- most all taken away from him, so that he had to start all over again, getting a new lot together. It was at this time, about the middle of October, that he was promoted to the rank of Captain.

During the last ten days before the signing of the armistice, Captain Baker got the first real opportunities for active fighting which he had had since the preceding June, and brought down two more Hun machines, his second and third. The first of these was a Fokker single-seater, one of a group of five which Captain Baker attacked while leading a formation of an equal number of his new pilots. The Hun fell in German territory northwest of Pont-a- Mousson and the wreck was visible from our lines, the American artillery completing its destruction. The second and the last plane which he brought down, was a two-seater which penetrated the American lines at a great altitude for the purpose of dropping propaganda leaflets among the infantry. Captain Baker and one of his pilots attacked him between nineteen and twenty thousand feet up and under Captain Baker's fire the Hun plane turned completely over on its back, throwing the observer out, the body falling in our lines. After falling upside down for about five thousand feet, the pilot, who had evidently been wounded, managed to right his plane and started for his own lines. He was again attacked and finally crashed a hopeless wreck about a mile inside the German lines. Shortly after the signing of the armistice we crossed the lines and found the skeleton of the machine, and scattered about it, quantities of the propaganda sheets with which it had been loaded.

His Success as Squadron Commander and Pilot

As a squadron commander, Captain Baker was very successful, for the officers and men under his command loved and admired him as did all who knew him. His pilots knew that he would never ask them to undertake anything which he would not do him- self, and that in him they had a friend who was constantly watching over their safety and who would never forsake them, regardless of the consequences to himself. His enlisted men knew that he was always thinking of their welfare and comfort and that any order which came from Captain Baker would be just and fair. I well remember one day last November when a patrol returning from the lines reported that it had last seen Captain Baker engaged in a hard fight with half a dozen Hun single-seaters and that they were afraid that he had gone down in the unequal fight. A look of consternation spread among the men, which was succeeded a few minutes later by a cheer, as the Captain's machine with its orange and black markings (he had adopted the Princeton colors and a Princeton tiger as the distinguishing mark of his squadron) was seen returning from the lines. Hobey had attacked a German formation by himself and had gotten into hot water, but with his usual skill and presence of mind had extricated himself with nothing worse than a bullet through one wing.

As a pilot, Captain Baker was one of the very best; he enjoyed flying and handled his machine with the greatest skill. I have never known a man who was more eager to fly or who tried harder to give to his country the very best that was in him. He fought whenever the opportunity offered and always with the most fearless courage. With all his great bravery, he at the same time used his head at all times and realized that there is a wide difference between true courage and foolhardiness, and that the latter accomplishes little but is really playing into the hands of the enemy. The only reason that Captain Baker's score in German machines brought down was not higher was because the chances which came to him were few. Had he had them or had the war continued, there is no doubt that his tally would have been a long one. During his service at the front he at all times flew the Spad single- seater pursuit machine and was entirely engaged in pursuit work.

As a man Captain Baker was a striking example of the finest that America can produce. In the course of several months of living and flying with him on the front I came to know him intimately. He was a thorough gentleman and a true friend on whom one could always rely. He was entirely unselfish and always thinking of others rather than of himself, and I remember one occasion on which I as his commanding officer had practically to order him to take credit for the destruction of a German plane, which by all the reports he and he alone had quite evidently brought down, because he felt that there was a possibility that some of his pilots might have had something to do with it, and he therefore wished to withdraw in their favor. In spite of all the well deserved praise that was heaped upon him for his success in athletics and in the service, he was totally unspoiled by it and he was modest almost to a fault.

His record as an officer was a splendid one, and he was a son of whom Princeton may well be proud.

No details have as yet been received of Captain Baker's death but as he fell at Toul he must have been buried at the cemetery of the hospital at Sebastopol, about two miles north of Toul. There he will lie in company with Lufbery, Putnam, and many others who played a great game through to the end and won, because they did their best.

Deaths in the Service

The number of Princeton men who have given their lives in the service has been increased to 115 by reports received during the past week. The following names are added to this roll of honor:

JOHN HARLAND MACCREADIE '19.

ANTHONY SAUNDERS MORRIS, JR., ‘15.

FRANCIS B. SHEPARD '06.

John Harland MacCreadie '19, of Lawrence, Mass., Chief Yeoman, U. S. N. R. F., died in service Dec. 7, 1918. Details of his death have not as yet been received. He left college in his sophomore year to volunteer for the war. He was an editor of The Princeton Pictorial Review.

Lieutenant Anthony Saunders Morris, Jr., '15, of Haverford, Pa., was killed in action Sept. 30, 1918. His father has received the following report of his death from an officer of his squadron: "Lieutenant Morris was on Infantry contact patrol during the Argonne offensive, and was shot down what was then seven kilometres within the German lines while strafing the retreating enemy. The wrecked plane was found in the region of Flaville, about five kilometres north of Varennes, on the east side of the Argonne Forest. He had completed his mission, and it was of his own volition that he did this hazardous work with its resultant end. With him at the time was First Lieutenant Cassius H. Styles, Infantry, U. S. A. Observer, of South Hero, Vermont. He was taken prisoner and is now returning home.

“The squadron deeply feels the loss of your son, whose work with the squadron began during the Saint Mihiel offensive. It may be said of him that his willingness to work was only surpassed by his bravery. Though mortally wounded, he landed his observer safely, and he will always be held in the squadron as one of the bravest and most gallant of its flying officers.

“You will no doubt be able to get full particulars of his work and heroism from the man whose life he saved, Lieutenant Styles.”

Captain Francis B. Shepard '06, of New York, died of tuberculosis in France Dec. 16. He had been in France since last May, in the Field Artillery. An account of his life appears in the obituary column.

WAR PHOTOGRAPHS WANTED

It is requested and very vigorously urged that the alumni of Princeton University who have served in any capacity with the American Expeditionary Force and who have snap-shot photographs, taken in France, forward copies of all such photographs, together with the necessary explanatory information to be used as captions, to the Officer in Charge, Pictorial Section, Historical Branch, War Plans Division, General Staff, Army War College, Washington, D. C.

These photographs are requested for incorporation in the permanent pictorial files, which will serve as the official photographic record and history of the war.

This was originally published in the January 15, 1919 issue of PAW.

No responses yet