Car Lab Projects Steer Students Toward Success

At this Fall’s Car Lab Demo Day, dozens of pairs of students presented their final projects to much fanfare, including matching custom T-shirts for all 90 students and four course instructors.

In Car Lab — a 30-year mainstay of the electrical and computer engineering program and the last required course for majors — students are given little guidance and challenged to use only basic parts to create an autonomous or remote-controlled vehicle. The car should also do “something interesting,” according to Andrew Houck ’00, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, during a five-minute presentation.

Over the years, pairs of students have produced cars that draw, dance, act like a dog, and goaltend. One car traveled down the hall to deliver a chocolate bar to Houck’s office. “I made sure they tested with my office,” Stephen Lyon, a professor of electrical and computer engineering who taught the first iteration of the course and still teaches it, said with a laugh.

Over the decades, the name of the course has changed — currently, it’s ECE 302: Robotic and Autonomous Systems Lab — as have its goals. When it was first offered in 1995, final projects were required to move at speed around a track, but about a dozen years ago, Houck revamped the curriculum.

One of the biggest challenges for the instructors has been figuring out “how to get the workload to be sensible,” according to Lyon, who recalled a Daily Princetonian piece from the 1990s that dubbed the course the “Nightmare on Olden Street.” Lyon said the instructors hope they’ve struck a balance that won’t “let it take over people’s lives.”

That doesn’t mean there aren’t still late nights — for students and instructors — but the experience is one that many find invaluable.

Before he took Car Lab, Joshua Lau ’26 heard things like “you’re [going to] be stuck in there pulling all-nighters every single day,” but he also heard it was “a super good engineering course [where] you’re [going to] learn a ton.”

Lau estimates that he and his partner spent roughly 125 hours working on their vehicle that can tell jokes, play music, and recognize faces. He realized afterward that everything he had been told “ended up being true.” While Car Lab was “extremely challenging and time-demanding,” he also learned a lot about engineering and improved general skills like time management and teamwork.

Trace Zhang ’26 and Edward Deleu ’26 spent about $150 and many long days on their autonomous photographer robot car that can follow a target and respond to voice commands. Once their demo was over, they sat back to watch what their peers had come up with while eating ice cream. Zhang reflected that they appreciated how Car Lab becomes a “character-building thing for each of the classes.”

“The class, as a whole, very much bonds in this course,” said Lyon.

“You are really accomplishing something,” Houck said. Car Lab “demands more time than a normal course, and it really is a rite of passage.”

Houck should know. As one of the first Car Lab students, he was given a faulty circuit board, and it took hours for him to identify and correct the error.

“Things don’t always go according to plan, and sometimes the things that get you really stuck seem unfair, but that’s sort of life as an engineer,” he said.

Jaime Fernández Fisac, an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering, was excited to co-teach the course for the first time this fall after hearing about it for years at the program’s graduation dinner, where “it’s not an exaggeration to say that about four [out of] five students will specifically bring up a Car Lab memory,” he said.

“Nothing turns you into an engineer as much as having to put together a system from scratch, beginning to end, and see it working.”

2 Responses

Benji Jasik ’97

1 Year AgoFun Way To Learn Engineering Principles

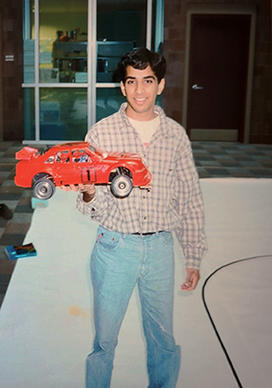

That picture is of Arvind Seshan ’97, and I believe the photo is from the winter/spring of 1996.

I have a few more photos from then that I’d be happy to share. I participated in the second year of car lab in 1996 and I believe the first year was 1995.

Great to see the class going strong — it taught me many wonderful engineering principles and in a fun setting.

Greg Humphreys ’97

1 Year AgoCar Lab Lessons Remain Useful

Best course I ever took. I still have my car 29 years later, and the things I learned in that class are still useful to me today.