Chemistry's new 'cathedral' a beacon to young faculty

As manipulators of molecules, chemists are the ultimate realists. So it comes as something of a surprise to hear David MacMillan, the chairman of the Princeton chemistry department, sounding almost mystical as he describes the department’s stunning new home: “When you walk into this building, it’s like walking into a cathedral,” MacMillan said.

“‘Cathedral’ is probably the wrong word, because it has this somber connotation,” he said. “We feel as if we are in this big, expansive, bright, open place — like having a new home that’s much bigger and nicer than your old home. You just feel so excited and proud.”

Frick Chemistry Laboratory, which cost $278 million and opened for classes this spring, is truly a wondrous place. As designed by the English architect Sir Michael Hopkins, it rises four stories from broad Taylor Commons, an atrium with offices on one side and labs on the other, and with airy white sculptures hanging from the 75-foot-high glass ceiling. For potion masters like MacMillan, it’s Hogwarts without the gloom. Said Martin Semmelhack, a member of the department since 1978: “Every morning, you walk in the building and feel it’s exciting.”

“Old” Frick — built in 1929 — was a lovely looking building, but it was no longer conducive to the pursuit of cutting-edge science in the 21st century. Not only was it hard to recruit world-class faculty and grad students to what was essentially a rabbit warren, but its cramped, gloomy hallways seemed to darken the department’s mood, along with its zeal for collaboration.

The result was that a decade ago, chemistry had become, in the most diplomatic formulation President Tilghman could manage, one of Princeton’s “least-strong departments.” As a microbiologist with close ties to chemistry, she was determined to change that, to make chemistry a “top-five” department, like math, physics, and biology. Princeton’s share of the royalties from the cancer drug Alimta (see story, next page) gave the project a huge boost.

Word of the new building has helped attract young chemists. Not only are grad-school applications up more than 25 percent in the past five years, but most are coming from the very top applicants, which was not true 10 years ago. At the same time, the yield is up — from 30 percent in 2005–06 to 44 percent in 2010-11. William Russel, dean of the graduate school and chairman of the committee that mapped a new path for the department, said that “letters from around the country speak of it as a top-five department.”

“There’s a gravitational pull to the place,” agreed Tom Muir, a leading chemist specializing in protein function in complex systems of biomedical interest who is soon to join the department, from Rockefeller University in New York.

MacMillan, a charming Glaswegian and a Scottish foodie, is a big part of that pull. His work is focused on chemical reactions that allow organic molecules (including medicines) to be built faster, more cheaply, more safely, and on the basis of completely new concepts. After stints at Harvard, UC Berkeley, and Caltech, MacMillan arrived at Princeton five years ago. He was not sure at first that he wanted to come, but was persuaded when he saw how ambitious the University’s plans were for the department.

MacMillan is aiming to gather not just the finest young chemists, but those “who care the most about being able to function as an interactive group,” he said. “We go out for dinners all the time. We have fun. That collegiality is what I’m most proud of.”

The new building reinforces that quite consciously. There are few walls between the labs and glass is everywhere, which means that one sees one’s colleagues constantly. “It’s completely flowing space,” said MacMillan. “So there’s not this territorial aspect to it — ‘Get your beeker off my table!’ ”

Something else that had to change was the department’s fundamental approach to chemistry: It was one of the last departments anywhere still clinging to the notion that chemistry should be an intellectual pursuit without regard for potential real-world applications. That, said MacMillan, was crazy, because “chemistry holds the solution to so many of the problems we are facing in the world today.”

Russel and his committee identified four areas for the new department to concentrate on: catalysis and synthesis, which look for new forms of chemical reactions; new alternative energies; searching for new materials; and chemical biology, which spurs the development of new biological medicines. All four hold the promise of making a real contribution to humanity.

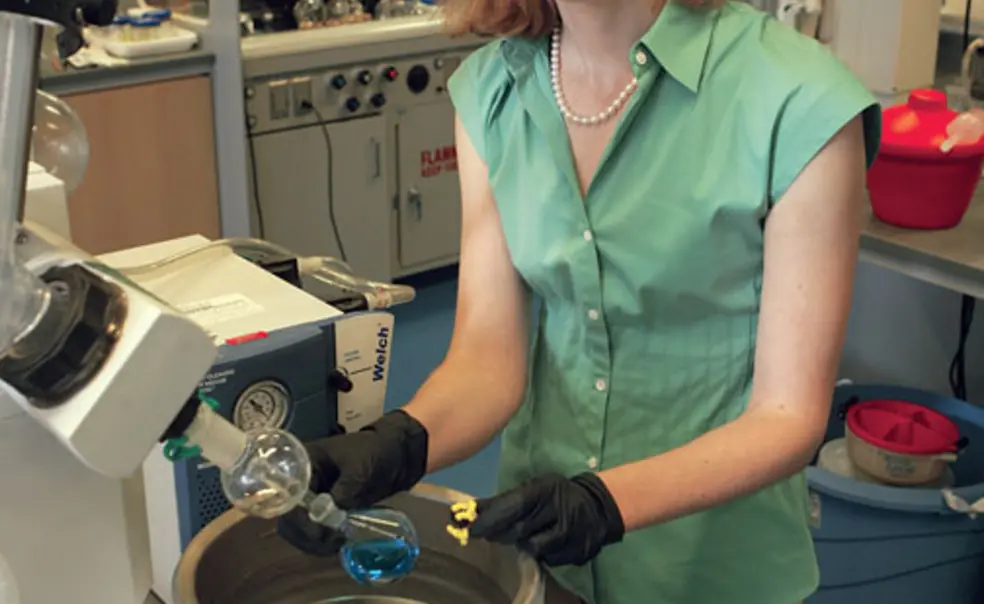

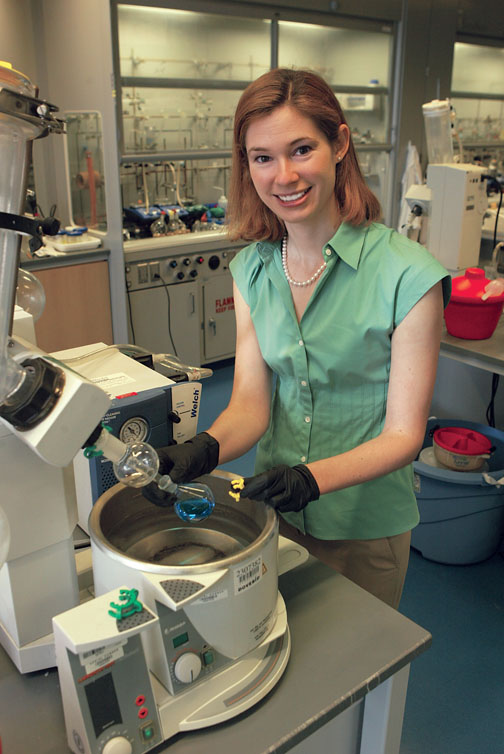

As an example, MacMillan pointed with excitement to assistant professor Abby Doyle’s work in organic synthesis and catalysis, which is changing the way people go about coupling molecules together. Just three years out of grad school at Harvard, Doyle — who is the daughter of former Princeton provost and current University of Pennsylvania president Amy Gutmann — may revolutionize the way pharmaceuticals are made. Persuading her to come to Princeton was a group effort, not to mention an absolute coup.

Doyle is one of nine new faculty members hired since the department began its reorganization five years ago. Another is Paul Chirik, one of the foremost organometallic chemists in the world, who’s just come from Cornell.

1 Response

Fred I. Greenstein

10 Years AgoAll in the family

The article on assistant professor Abby Doyle (Campus Notebook, May 11) fails to mention that her father, Michael Doyle, was a member of the Princeton faculty. He is now at Columbia.