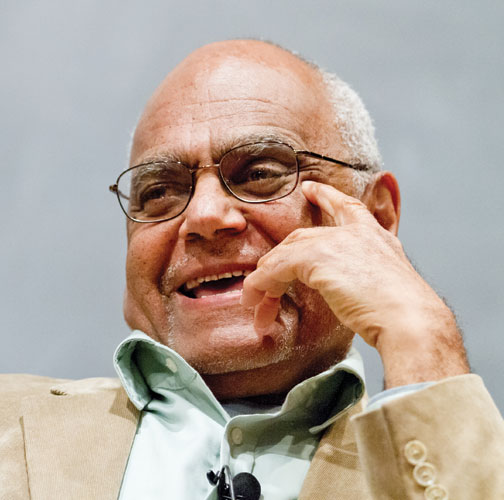

Civil-rights leader Bob Moses, on education

Fifty years ago, Robert Parris Moses was field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), traveling through Mississippi to register black voters. In 1964, he organized the Freedom Summer project and helped form the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which sought to seat black delegates at the Democratic National Convention. Almost 20 years later, Moses used a MacArthur Fellowship to create the Algebra Project, which focuses on improving minority education in math. He is a visiting lecturer on campus this year, co-teaching a course with Professor Tera Hunter called “Liberating Literacy.”

Tell me about your class.

We have been trying to form a narrative about the country connecting work, education, the Constitution, and issues dealing with civil rights and justice during the era before, during, and right after the Civil War. For example, we have been reading an article in The Yale Law Journal by Judge Goodwin Liu, who argues that the citizenship clause of the 14th Amendment provides a constitutional right to an education. We have had lectures by professors who have done original research on freed people’s conceptions of work and education during Reconstruction.

Do your students know much about the civil-rights movement?

Most of the young students don’t know about SNCC. There’s a made-up story about the civil-rights movement that parallels the made-up story about the country. It revolves around Martin Luther King Jr. and the idea that there were some big demonstrations — the March on Washington, Birmingham, the march from Selma to Montgomery — and that in response to those media events, the country shifted.

The problem for young people is that this narrative doesn’t explain how they can enter into a struggle about the major issues the country currently faces. It overlooks the importance of people like Ella Baker, who brought together young people who had been organizing sit-ins in out-of-the-way places around the South. That led to the creation of SNCC, but that part of the story is rarely told. You have to understand what actually happened then in order to understand what might happen today or tomorrow.

Martin Luther King Jr. has been elevated into the pantheon of American heroes. Is singling out one person a disservice to the movement?

America has always elevated individuals around the major events facing the country. That’s not a disservice — it’s what America does, but it shouldn’t be only what America does. It’s usable if people decide to use it. You can use King to talk about the issues that he was trying to address and their current manifestation.

You’ve done a lot involving education. What is behind the Algebra Project?

In Mississippi in the 1960s, we worked to get sharecroppers to demand their right to vote and then act on that demand. The Algebra Project, at its core, is trying to do the same thing around education, using math. How do you get students to demand their rights?

How do you do that?

The Algebra Project targets the bottom quartile. As opposed to looking for the math talent, it tries to find the math floor. Now, we either forget about students at the bottom or try to remediate them to death. We’re looking at what math to teach and how to teach it so those students might be willing to do it.

Why has the racial disparity in educational performance been so hard to overcome?

We have been running an education system that is driving a caste system. We agree to have failing schools with the caveat that we also have a plethora of programs to rescue different categories of students from them. Almost every program you can think of — charter schools, vouchers, affirmative action — all rescue different categories of students. We can’t announce that as an education policy, but that’s what we do.

Is there any place in America that presents a model of the society you would like to see?

If there are any, I haven’t lived in them. Put it that way.

— Interview conducted and condensed by Mark F. Bernstein ’83

No responses yet