Class Close-Up: History of Mathematics Starts 4,000 Years Ago

Students learn ‘a whole landscape of the subject. It’s a crash course,’ says visiting fellow Alex Kontorovich ’02

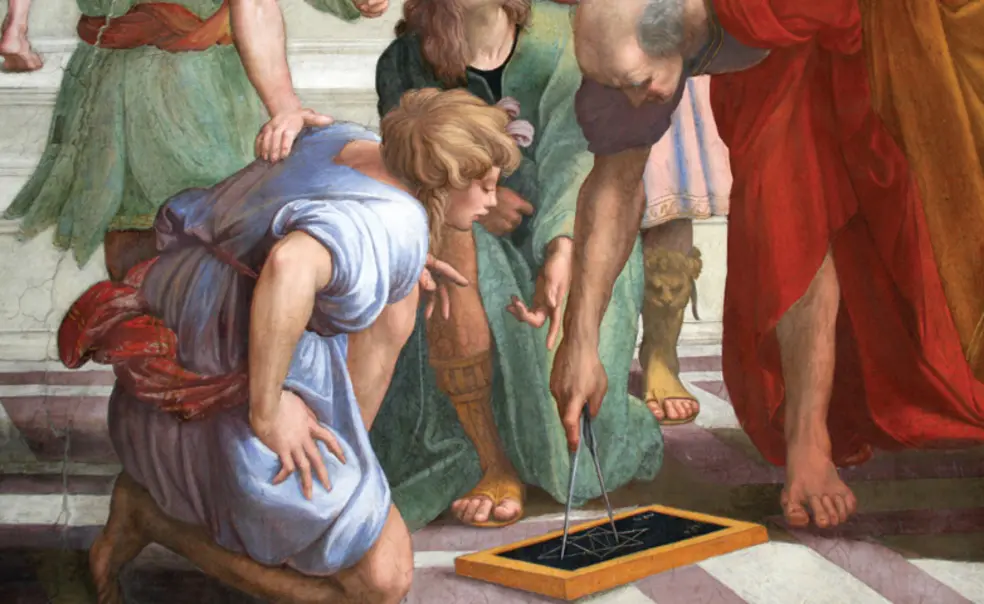

About 500 years ago, Italian mathematician Scipione del Ferro became the first to solve depressed cubic equations, but he never published his solution and waited until his deathbed to describe it to a student. That decision to stay silent, Alex Kontorovich ’02 explained to his History of Mathematics class, came down to norms. In Italy at the time, it was typical for mathematicians to duel each other — not with knives or guns, but math problems — for jobs; del Ferro wanted to keep his solution secret as a form of job security. It didn’t become public for about a decade.

“Mathematics is space-time dependent,” Kontorovich, a visiting fellow at Princeton and professor at Rutgers University, told his class.

“I’m very impressed by the drama of this,” one student said.

While Kontorovich said he thinks of History of Mathematics as more math than history, he does not consider it a math class because “every math class is targeted toward [learning] a skill,” whereas he wanted his students to “get an appreciation for what’s going on in those other [math] courses” through “a whole landscape of the subject. It’s a crash course.” He taught it roughly chronologically, starting about 4,000 years ago with the Babylonians.

The course was designed for non-STEM majors, but Kontorovich wishes he had taken it when he was studying mathematics at Princeton because “we didn’t have a class that would take all of this mathematical culture and synthesize it.”

The course is not new to Princeton, though it had been absent from the University’s offerings for years before Kontorovich, who previously taught it at Stony Brook University, revived it this past fall. About 35 students from freshman to senior year enrolled.

The math was likely similar to what students did in high school, but Kontorovich hopes they now better understand the context and importance. “We’re constantly reconnecting things that happened 2,000 years ago to things that happened much more recently,” he said, such as relativistic adjustments that are needed to calculate GPS.

Readings included Journey Through Genius: The Great Theorems of Mathematics by William Dunham, and the midterm and final were written exams with math problems and a few related history questions.

Amelia Hanbury ’28 said the math was “not simple” and “challenges you to think,” but she appreciated that Kontorovich presented material “as a story” that “creates characters out of these mathematicians” and showed how they reasoned through problems without calculators or the internet.

She also saw how knowledge transformed from “a kind of a weapon, almost,” to “something that can be shared,” and believes the former approach “may have hindered our ability to learn more things about our world.”

No responses yet