Collection of Writings and Reflections Honors Poet Yusef Komunyakaa

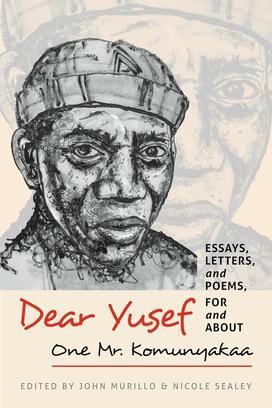

The book: Dear Yusef (Wesleyan University Press) contains a collection of essays, letters, and poems praising the work and influence of Yusef Komunyakaa. In addition to his writings, this collection includes reflections from poets, former students, admirers, and others. Terrance Hayes, Sharon Olds, and Toi Derricotte are among those who give Komunyakaa his flowers. In addition to celebrating Komunyakaa, this book also highlights the power of poetry as an art form to inspire and transform the world.

The editors: Nicole Sealey is a lecturer in Princeton’s Lewis Center for the Arts. She is a poet and author. Among her books are The Ferguson Report and Ordinary Beast. Her work has appeared in The Atlantic, The New Yorker, and Poetry London. She’s also the winner of various awards including the Rome Prize in Literature and the Stanley Kunitz Memorial Prize.

John Murillo is a poet and author of various books including Up Jump the Boogie and Kontemporary Amerikan Poetry. His honors include The Four Quartets Prize from the T.S. Eliot Foundation and the Poetry Society of America, and two Larry Neal Writers Awards, among others. His work has appeared in American Poetry Review, Poetry, and Best American Poetry. He is an associate professor of English and director of the creative writing program at Wesleyan University.

Excerpt:

Introduction

In May 2019, Cave Canem Foundation and New York University’s Creative Writing Program, in partnership with the PEN World Voices Festival, held a day-long celebration of the life and work of one of the most impactful American poets of the last halfcentury. Yusef Komunyakaa: A Celebration brought together a veritable “Who’s Who” of contemporary American poetry to honor a poet who, it turns out, is as beloved for his teaching and mentorship as he is celebrated for his creative work.

This anthology finds its genesis in, and moves in the spirit of, that day-long symposium. It also owes a debt to an earlier anthology dedicated to another of our beloved poet-teachers — Coming Close: Forty Essays on Philip Levine, edited by Mari L’Esperance and Tomas Q. Morín for Prairie Lights Books in 2013. Upon seeing Phil’s great joy at being able to hold that book in his hands, to read all that his students and friends had to say about him, we knew we had to pay similar tribute to Yusef. Our only regret is that it has taken us this long. While both the Komunyakaa symposium and the Levine anthology predate Covid, our anthology feels like part of a larger trend that seems to have picked up since the pandemic. Now more than ever, it seems, readers and writers are making greater efforts to honor elders and contemporaries while they are here to receive the praise. Recent tributes that come immediately to mind include a virtual reading held in honor of poet and Cave Canem co-founder Toi Derricotte by the Brooklyn Book Festival in October of 2021 and Trying for Fire: A Tribute to and Celebration of Tim Seibles, which took place at the Association of Writers and Writing Programs (AWP) conference in 2022. As of this writing, there is an essay collection honoring Sharon Olds in the works by the University of Michigan, and another dedicated to Komunyakaa to be published by the Louisiana State University Press. We say, the more the merrier. Clearly, it is flower-giving time.

If you’re reading this, you already know who Yusef is and what he means. But, just in case: Yusef Komunyakaa is the author of nearly 20 volumes of poetry and prose, and his plays and librettos have been performed to international acclaim. His honors include the Pulitzer Prize for poetry, the Wallace Stevens Award from the Academy of American Poets, the Poetry Foundation’s Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize, and the William Faulkner Prize from the University de Rennes, among others. He served as chancellor of the Academy of American Poets from 1999–2005 and has taught at Cave Canem’s week-long retreat, as well as at many universities, including the University of New Orleans, Indiana University, Princeton University, and New York University, where he served, before retiring in 2021, as Global Professor and Distinguished Senior Poet in the creative writing program. He has taught your best teachers and is most likely your favorite poet’s favorite poet. The word “anthology” derives from the Greek anthos (flowers) and logia (collection, or gathering). This book, then, is a bouquet. A bouquet for one whose generosity, kindness, and wisdom, whose guidance, mentorship, and friendship have made rich the lives of each of the contributors. It was an honor and a joy to gather these flowers for you, Dear Yusef. — John Murillo and Nicole Sealey

What Counts: Letters and Personal Essays

Dear Yusef,

This is the thing, I’m not sure if I should call you Yusef or Mr. Komunyakaa. And I say Yusef, because the only Yusef, since I first read your work, is Yusef Komunyakaa. You have become the embodiment of the name and turned the name into every part of speech imaginable, including myth and legend and the story we tell in the barbershop about the cat who ran a threeminute mile or leaped and snatched a quarter from the top of the backboard.

The story I tell most often about poetry begins with the hole. A contraband copy of Dudley Randall’s Black Poets slipped under my cell door in solitary, introducing me to Sonia Sanchez, Claude Brown, Nikki Giovanni, Lucille Clifton and Etheridge Knight and Countee Cullen and all of the rest of them. Less often told is what happened weeks later. Shipped off to a super-maximum-security prison in the gutted side of a mountain, a young brother with dreadlocks and a shank buried on the yard would let me borrow Michael Harper’s Every Shut Eye Ain’t Sleep. He said, Shahid, I think you’ll dig this, as if there was something about the way I moved around those circles of incarcerated and suffering men that suggested poetry.

Happenstance is one of those words not used often enough is what I think. But it’s all like the happenstance that led me to naming my second son after Thelonious. First hearing the name in “Elegy for Thelonious,” I carried it around in my head for years before saving up some change and buying me a Thelonious Monk cassette while in prison. “Untitled Blues,” “How I See Things,” “Facing It,” I know you’ve heard this before—how some of your words didn’t just create meaning for a young’un hoping to spin words on a page, but made them believe such a thing had value. And now we all, after getting hip to your work, have decided that we want to turn image into legacy. That’s not all of what I mean though. In the same anthology, Rita Dove writes “if you can’t be free, be a mystery” in “Canary.” What has always struck me about that line is how you, Mr. Yusef Komunyakaa, have always finessed what it means to be a mystery. The source of the transparency of your mind on paper has always been a kind of elusive—as if your wisdom just happened.

Back then, I had no way of knowing who Yusef Komunyakaa the man was. I wasn’t even certain if you were Black. The name Komunyakaa as mysterious as whatever the source of your stories were, except, truly, your stories almost immediately felt like they belonged to me cause I know I was born to wear out at least one hundred angels. At least I came to know that after reading “Anodyne” and remembering that it is okay to love the ragtime jubilee behind my left nipple. And still, what I mean is that I couldn’t place how a Black man came to know all the things in your poems and know himself as Yusef Komunyakaa.

This letter started out as a would-be review of your new book, Everyday Mojo Songs of Earth. But lately I’ve been reading Milton’s Paradise Lost. Something about this last reading of Paradise has me thinking that Milton’s problem is that he wanted to workshop God. And he wanted to pull Adam and Eve into it. They resisted after the fall, but Lucifer still had some punctuation he was at odds with. It ain’t end too well for him. And me believing that some poets are, at least, prophets, if not the voices of some g-d, I figure I know better than Lucifer and the pair. And so I won’t go tinkering with messages from glory. I wonder if you dig Rakim. Generally, I know how you feel about hip hop. But Rakim, nicknamed the G-d MC, always had me recognizing what it meant to want to be more on a page. That’s how your work has been, in a way. And so the review wasn’t in me. Picking up Mojo Songs was more a walk back down memory lane.

You know yourself in ways we avoid. And don’t nobody else make the reader fall into that voice until they’re becoming more cognizant of themselves. “I want each question to fit me / Like a shiny hook, a lure / In the gullet,” you write in “When Dusk Weighs Daybreak.” And I’m thinking maybe that’s the rub. These lines reveal how to make a man understand himself, and then admit the cost: “I need a Son House blues / To wear out my tongue.” A different way of saying all of this is that in those first-person poems, in the space of those narratives, I became somebody else. A wiser, hipper cat with more than just the stories that carried me to prison. And sometimes, in doing all that, I become afraid of what I know. Take the end of one of your new joints, where you write, “To stand naked before a mirror / & count the parts is to question the whole / season of sowing & reaping thorns.” Who is brave enough to walk into the world with that knowledge?

I be telling myself how I met you in prison and take solace in that. Cause, like many a young writer, I want to know the man behind the poems. But prison teaches you to give a man his privacy. And so, when I met you years ago at Cave Canem, I was awed. But just wanted to be chill. And maybe I regret this. Now believing that, now deeply believing that part of all this work of art is to spend time listening. Though there is something to be said about what it meant to watch you in a chair alone sipping your drink, having earned whatever rest or weariness you wanted to have, in solitude. I should have told you though, how all those years ago your words were a part of the yarn that I spun into the loudmouthed poet who felt invisible and so needed to be seen that I would have wept if my body knew how. Where I grew up only cowards wept though. And while I was never one for accurately landing a jab or a hook, I knew how to hold my tears. What am I saying? There were things I might have said, but the wild thing is that just watching you chill for a moment made me feel seen and made me know that the accumulation of words that led to that moment meant something. I’m from the generation of Black boys who found their elders in prison cells and mostly forgot them if we were lucky enough to get free. And then your poems turned you into one of the first men who knew my name.

Once, you, while critiquing one young poet’s sprawling poem, said something to the effect of, see, the poems ends ten lines up from the period. If there was a lesson in that, I figured it was that sometimes in life you run past where you want to be to land where you need to be. But you also must be able to check and see if you’ve run too far. First time I realized I could turn to the past and find where I needed to be was in your words. That’s the thing so many of us are after, how to return to yesterday to find the scaffolding for tomorrows. And I know, like a lot of my peers, I’m still just trying out your notes. Hoping that the few times I get it right, I’m not afraid of whatever unravels between the lines.

Take care, Dwayne Betts

Excerpted from Dear Yusef edited by John Murillo and Nicole Sealey. Copyright © 2025 and published by Wesleyan University Press. Reprinted with permission of the editors.

Reviews:

“In this moving tribute to Yusef Komunyakaa, friends, students, and admirers share their personal connections to the legendary poet and teacher. This is a well-deserved honor for Komunyakaa and a must-have for his fans.” — Publishers Weekly

“Dear Yusef is a bountiful bouquet of deep love, and this poet deserves every last rose.” — Lauren K. Alleyne, executive director of the Furious Flower Poetry Center

No responses yet