College and Civil War Reminiscences

Inasmuch as the Class of which I was a member, — the Class of 1865, — was in college from the beginning (1861) to the end of the Civil War (1865), it has been suggested that it might be interesting to the alumni of later years if I should recall a few of the incidents and events of that military era in Princeton. Our Class entered in August, 1861, but a few months after the opening of the war. At that time there was no northern college more popular at the South than Princeton and as a natural result there was a comparatively large number of southern men among the undergraduates at the outbreak of the war.

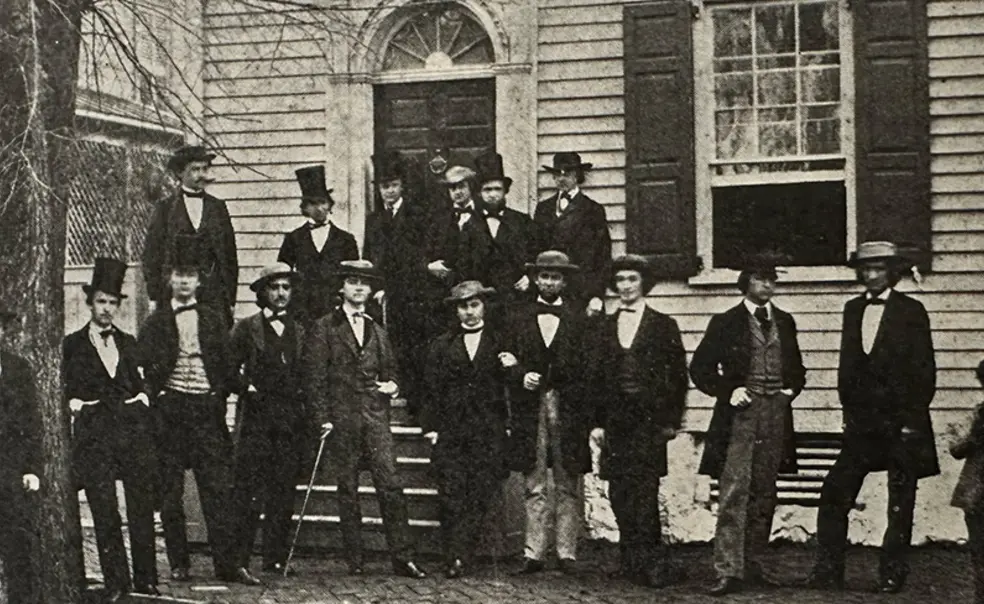

As I entered the campus in June for my examination the first scene that attracted and impressed me was the Class of 1861, assembled at the east end of Nassau Hall, bidding one another an affectionate farewell, the parting being especially pathetic from the fact that northern and southern students were enlisting in the service of their respective sections, not a few of them to give up their lives to the service of their country.

Some of the southern students remained in college throughout the four years, though in the summer of 1863, midway in the course of the war, a considerable contingent from the upper classes entered the northern or southern army. In recalling the experiences of these stirring days, nothing impresses me more deeply and favorably than the fine, generous spirit that existed among the northern and southern students in their college friendships and intercourse, — often, indeed, when the intense excitement of the time would seem to have made it impossible for human nature not to assert itself on the vindictive side and in grossly objectionable forms. While here and there individual instances of sectional temper might be noticed, the prevailing spirit was gentlemanly and considerate. The only notable exception to this was in connection with the nomination of C. L. Vallandigham, a bitter opponent of the national war policy, for Governor of Ohio. In June, 1864, the “rebel sympathizers,” so called, celebrated his return from banishment on account of his treason, by a bonfire around the old cannon, cheering for Jefferson Davis and the Confederacy.

That was quite too much for the loyal students and around “that same old cannon,” as the record states it, they piled the wood, hung the Ohio nominee in effigy and cheered for “Honest Old Abe as our next President,” while stirring speeches by the professors added to the interest of the celebration.

Richmond’s Fall and Lincoln’s Death

A few of the incidents that I find recorded in my notes of that era are the following:

March 26, 1861 — The gunboat Naugatuck passed through the canal.

August 30, 1862 — Students held a war meeting at the gymnasium.

September 12, 1862 — Several members of ’63 left to join the army.

October 11, 1862 — Political meeting in Merced Hall, addressed by professor and students.

Tuesday, April 4, 1865 — Celebration of the Fall of Richmond, torch-light procession, illumination of North College, and speeches by professors, followed by a “huge bonfire.”

At this great Union celebration were a few southern students.

April 15, 1865 — New of the assassination of Lincoln. “Friends and foes were alike mourners.”

Flags were hung at half mast, bells were tolled, North College and the Halls and the Chapel were draped and memorial services were held, President Maclean preaching on the Sabbath an appropriate memorial sermon.

Monday, April 24, 1865 — President Lincoln’s funeral train passed the “new depot” at the Junction, the students going over in a body to pay their last tribute to the martyred patriot.

During the larger part of our college course the Pennsylvania Road ran from Trenton to New Brunswick along the edge of the canal, the old depot being at the foot of Canal (now Alexander) street, whither the students repaired whenever troops went through or any distinguished military personage.

It was on these occasions that we heard stirring addresses from Drs. Alexander, Atwater, McIlvaine and Duffield, as mounted on a box or barrel they awakened the patriotic fervour of the students.

No Such Nervous Tension Then as Now

Another striking feature of the era was that the orderly procedure of college exercises was not materially affected during the four years of war. Occasionally, on the event of a signal victory of the northern army, a few hours or perhaps a day of interruption might occur, but no general or protracted suspension of academic work, no such nervous tension existing as that which we have noticed in these tragic days of international strife. The present world-struggle really seems to be nearer in its daily developments and its frequently depressing influence than the Civil War was, though waged at our very doors.

From time to time, as the war went on, the students were subject to military drill, as they are now, and yet it seemed to fit in with the regular collegiate activities and in no sense to dominate them. And thus in these days before our very eyes the old local war of the States in the early sixties is recalled as we witness the gigantic conflict that is now waging, and in each case alike the struggle is on behalf of human freedom and the rights of man.

In a memorable letter addressed to the Trustees of the college by President Lincoln, December 12, 1864, acknowledging the degree of Doctor of Laws conferred upon him by the Board, he significantly writes: “Thoughtful men must feel that the fate of civilization upon this continent is involved in the issue of our contest”; and with equal truthfulness it may be said that the fate of civilization on this continent and the world at large is involved in the issue of this contest.

Thus it is that standing at the “old cannon” the intervening years from 1861 to 1914 are united, and we can almost hear in faint reverberation the guns of Gettysburg and the Marne sounding out the call for universal justice and freedom.

This was originally published in the May 23, 1917 issue of PAW.

No responses yet