Comparing the Two Reconstructions

Has the 20th century really done better in civil rights than the 19th century did?

Editor’s note: This story from 1979 contains dated language that is no longer used today. In the interest of keeping a historical record, it appears here as it was originally published.

Ten years ago during a class discussion of the backlash of the 1870s against the radical civil rights gains of Reconstruction, one of my students said that this time, a century later, the story would be different. Having grown up with the civil rights revolution of the 1960s and having thus acquired greater enlightenment than their forebears, the members of his generation would make sure that no backsliding occurred when they moved into positions of power. Similarly, despite the setbacks of the past decade, last year one of my graduate students concluded an examination essay on racial attitudes during the Civil War era with the assertion that her generation had largely remedied the failures and overcome the racism of its predecessors.

These statements should not be dismissed as the naïve arrogance of youth, for the reflect widely shared views. Today, the first Reconstruction is generally considered a failure and the second Reconstruction — as the civil rights reforms of the mid-20th century have come to be called — a success. Buy a careful comparison of the two eras calls into question our right to patronize the past. It is not at all clear that we have done any better; in fact, we may not have done as well.

The first Reconstruction is usually defined as the period from 1863, when the North freed the slaves and granted them equal civil and political rights, to 1877, when it abandoned them to their fate by withdrawing federal troops from the South as part of a compromise to resolve the disputed presidential election of the previous year. No such clear signposts mark the beginning or end of the second Reconstruction. Authorities differ as to whether its origins should be dated from the report of the Truman Civil Rights Committee in 1947, the Supreme Court’s Brown decision in 1954, the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955, the sit-ins of 1960, or some other event. Nor is there a consensus as to when it ended or even whether it has ended.

Nonetheless, the parallels between the two Reconstructions are striking: President Kennedy’s eloquent support for civil rights legislation in 1963 came almost exactly a century after President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 reinstated many provisions of the Civil Rights Acts of 1866 and 1875. Supreme Court decisions based on the 14th Amendment occurred almost on the centennial anniversary of its adoption. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 accomplished some of the same things as the Reconstruction Acts of 1867; and subsequent black victories at the polls were in some ways reminiscent of the election of hundreds of black county officials, state legislators, lieutenant governors, and U.S. congressmen and senators in 1868-75.

Until recently, there have been four principal interpretations of the first Reconstruction:

- The conservative or “Southern” interpretation, which dominated the field for the first half of this century, portrayed Reconstruction as an era of fraud and repression imposed on the helpless white South by vengeful Northern radicals and rapacious carpetbaggers who duped ignorant black voters in an orgy of misgovernment and plunder.

- The “Progressive” interpretation, which enjoyed a vogue in the 1930s, pictured the reconstruction policy of Northern Republicans as a cynical plot to protect industrial capitalism from a resurgent Southern-dominated Democratic party by smuggling subtle pro-corporation language into the 14th Amendment and creating puppet state governments in the South to insure continued Republican control of the national government.

- The “Marxist” interpretation, also popular in the 1930s, described radical Republicans of the 1860s as bourgeois revolutionaries who destroyed the Old South’s feudal institutions and replaced them with free, democratic, capitalist institutions as part of the world-historical march toward socialism.

- The “Liberal” interpretation, which gained pre-eminence in the 1960s, was itself a product of the second Reconstruction and, accordingly, emphasized the parallels between the civil rights legislation of that decade and Reconstruction measures of the 1860s. Both sprang from a creative alliance between egalitarian activists and political pragmatists; both attempted to extend equal rights to black people; both achieved triumphs of justice over oppression, of democratic nationalism over reactionary regionalism.

Despite their differences, all four interpretations have in common the theme that the 1860s were years of radical change in the status of black people. The foremost proponent of the Progressive view, Charles A. Beard, called the Civil War and Reconstruction “the Second American Revolution” because they transformed the United States from a Southern-dominated agricultural society into a Northern-dominated industrial nation.

In addition, all four consider the 1870s a decade of reaction during which most of the racial progress of the 1860s was wiped out. By 1876 the Democratic party had regained control of the House of Representatives and of all but three Southern states, and claimed the White House itself in the disputed presidential election of that year. Although the Republican claimant, Rutherford B. Hayes, was inaugurated in 1877, he achieved the presidency only at the price of concessions to the South, including “home rule” — which meant the rule of Southern states by the white-supremacy Democratic party.

In the Progressive interpretation, this was not so much a counterrevolution as a compromise by which Northern capitalists who had never really believed in racial equality made their peace with the now-friendly New South. For the Southern school, the Compromise of 1877 was a triumph of decency and civilization over darkness and misrule. For the Marxist and Liberals, it was a counterrevolutionary betrayal of the revolutionary gains of the 1860s.

There is a fifth interpretation, however, the rejects the idea of a counterrevolution in the 1870s on the grounds that no revolution had occurred in the first place. This “neo-Progressive” school holds that during and after the war the policy of the Union army and the Freedmen’s Bureau toward the emancipated slaves was one of “stability and continuity rather than fundamental reform.” The goal of Reconstruction, then, was a disciplined, tractable, cheap Southern labor force rather than an independent, land-owning black yeomanry. The Republicans who freed and enfranchised the slaves were themselves infected with racism, which limited their vision of the freedmen’s “place” in the new order, undercut Reconstruction legislation — whose revolutionary potential was largely a byproduct of its attempt to strengthen the Republican party — and foreshadowed the quick and easy retreat in the 1870s from the limited and tainted gains of the 1860s.

In the words of two leading advocates of this interpretation, Reconstruction accomplished no “fundamental changes” in “the antebellum forms of economic and social organization in the South.” The Civil War was therefore “a tragedy unjustified by its results.” The “new birth of freedom” that Lincoln called for in his Gettysburg Address never occurred. “Sadly, we must conclude that those dead die in vain,” since “real freedom for the Negro remained much more of a promise, or a hope, than a reality for nearly a century.” “What little progress Negroes have been allowed to achieve,” wrote a neo-Progressive historian in 1969, “has occurred almost exclusively in the past 15 years.”

This brings us full circle to my graduate student’s exam statement: Reconstruction accomplished nothing for blacks but false promises; only our generation has achieved real progress. Apart from its failure to acknowledge that much of the progress in the 1950s and 1960s was based on constitutional amendments and legislation passed during the first Reconstruction, this argument is guilty of reading history backwards, of measuring change over time from the point of arrival rather than the point of departure.

The resulting false perspective will always diminish the apparent amount of change. It is like looking through the wrong end of a telescope. A simple arithmetical analogy illustrates the point. On a scale of 1 to 10, a change from 1 to 3 is an increase of 200 percent. But measure from the perspective of 10, it appears to be an increase of only 20 percent. From the standpoint of 10 this is minimal change, a terrible indictment of a scale that limits advance to 3. But viewed from the standpoint of 1, it is marvelous progress.

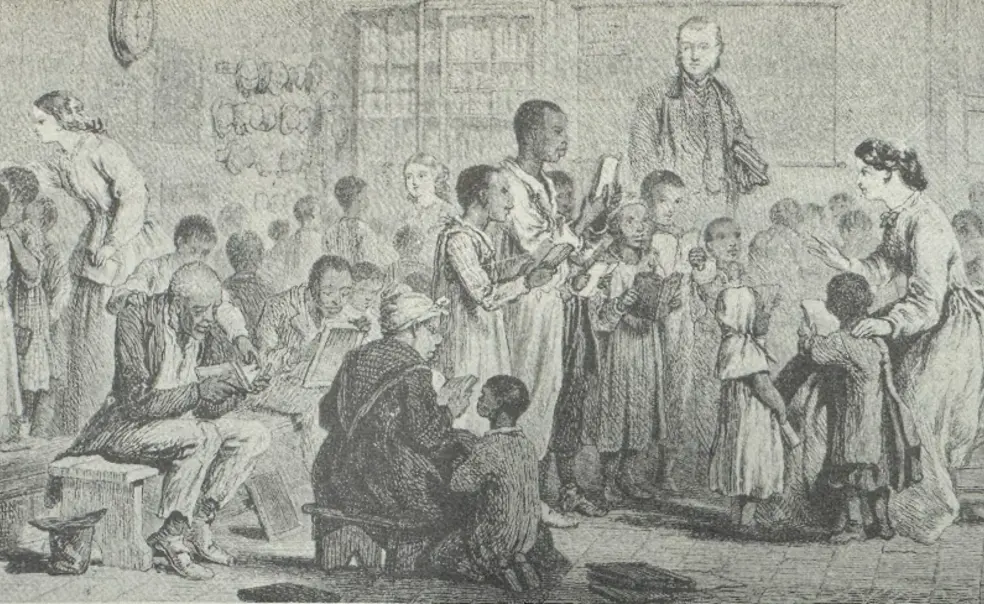

To apply this analogy to historical reality: Black literacy increased from about 10 percent in 1860 to 30 percent in 1880. This appears minimal and shameful from the standpoint of nearly 100 percent literacy today. But for a people denied access to literacy while living in one of the world’s most literate countries in 1860, the sudden opening of the opportunity to learn to read and write, limited though it was, represented radical change. In 1860 only 2 percent of the black children in the United States were attending school; by 1880 the figure had grown to 34 percent. During the same period the proportion of white children in school rose only from 60 to 62 percent. In no other period of American history has either the absolute or relative rate of black literacy and school attendance increased so much as in the 15 years after 1865.

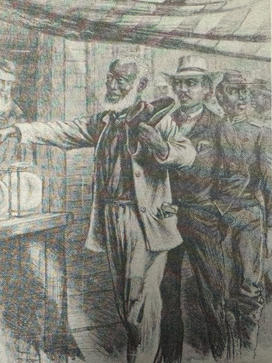

If one turns from education to politics, the same radical changes appear. At the beginning of 1867 fewer than 1 percent of American black adult males could vote. Three years later all one million of them possessed the franchise, and at least 700,000 voted in the 1872 presidential election. In 1867 no black man held political office in the South; in 1870 at least 15 percent of all Southern public officials were black. By way of comparison, 1979 — 14 years after passage of the Voting Rights Act — fewer than 3 percent of Southern officeholders are black.

The Civil War and emancipation also accomplished the most sudden and vast redistribution of capital in American history. $3 billion in human capital (equivalent to $22 billion today) was transferred from slaveholders to former slaves who now owned themselves. In One Kind of Freedom, economic historians Roger Ransom and Richard Sutch attempt to calculate the benefits of emancipation for blacks. They conclude that under slavery blacks had received as subsistence only 22 percent of the output they produced and with freedom this jumped to 56 percent. From 1860 to 1880, the per capita real income of blacks increased by 46 percent, while that of Southern whites actually declined by 36 percent. Put another way, black per capita income jumped from a relative level of only 23 percent of white income in 1860 to 52 percent by 1880. Although whites were still way out in front, this substantial relative redistribution of income within the South was unparalleled in our history.

As for landowning, a vital measure of wealth in an agricultural society, the picture at first glance appears bleak. In 1880 about a third of the blacks employed in Southern agriculture were farm laborers owning no land. Of the remaining two-thirds, classified in the census as farm operators, only 20 percent owned their land. At the same time two-thirds of the white farm operators owned their land, and the average value of the farms owned by whites was more than double that owned by blacks. The former slaves were unquestionably at the bottom of the economic ladder.

Yet viewed in another way, the 20 percent who owned their farms in 1880 represented an extraordinary increase over 1865, when scarcely any blacks owned land in the South. The freedmen’s limited success in acquiring land represented, once again, a greater rate of progress than any comparable period of American history. During the same 15 years, the proportion of Southern white farmers who owned their land was declining from four-fifths to two-thirds, as postwar poverty and a ruthless credit system created widespread rural bankruptcy.

The point here is not that the first Reconstruction was a golden age in black history. Of course it was not. Despite educational gains, most blacks were still illiterate at the end of Reconstruction. Despite voting and holding office, they did not achieve political power commensurate with their numbers. (In South Carolina, however, they did constitute a majority of elected state and federal officeholders in 1868-76, something never again matched in any American state.) Despite economic gains, most blacks were sharecroppers and wage laborers, victims of an exploitative agricultural system in the poorest sector of the American economy.

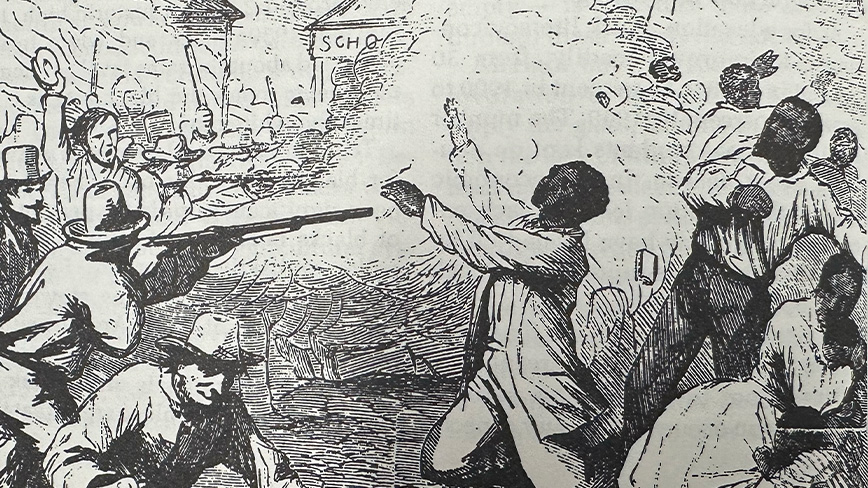

They were also the victims of violence and intimidation practiced by the Ku Klux Klan, the White League, the Red Shirts, and similar organizations — and, in a way, that is the point. This was counterrevolutionary violence. Southern whites of the 1860s believed they were living through a revolution, even if some modern scholars do not. “The events of the last five years have produced an entire revolution in the entire Southern country,” declared a Memphis newspaper in 1865. It was the “maddest, most infamous revolution in history,” said a South Carolinian in 1867. Black spokesmen made the same point in reverse. “The good time which has so long been coming is at hand,” announced one. “We are on the advance,” asserted another.

Black leaders were well aware that the revolution was incomplete. The glass was only half-full. Modern scholars who point out that it was still half-empty are of course also correct. But to conclude therefore that no “fundamental changes” had taken place, that “the new birth of freedom never occurred” — that the glass remained completely empty — is a mistake those who lived through these events did not make.

All right, but what about that counter revolution of the 1870s? Did it not empty the glass, leaving to our generation the task of filling it again? No — at least not immediately, and not entirely. Not all the gains of Reconstruction were overthrown when the troops pulled out in 1877, and some of them never were.

The full-scale disfranchisement and legalized segregation of blacks in the South occurred in the 1890s and 1900s, not immediately after Reconstruction. Blacks continued to vote in substantial numbers in most Southern states until the 1890s. The percentage of Southern Negroes voting in the 1880 presidential election was almost equal to that of Southern whites. Black turnout actually exceeded white turnout in some state elections during the 1880s. The Republican party, predominantly a black party in the South, got about 40 percent of the Southern vote in the three presidential elections of that decade.

Furthermore, hundreds of black men were elected to Southern state legislatures after Reconstruction: 67 in North Carolina from 1876 to 1894; 47 in South Carolina from 1878 to 1902; 49 in Mississippi from 1878 to 1890; and similar numbers elsewhere. Every Congress but one from 1869 to 1901 had at least one black representative from the South. The frequent newspaper stories during the last decade stating that “so-and-so is the first black congressman (or state legislator, county sheriff, etc.) elected in such-and-such a Southern district since Reconstruction” are wrong.

As for education, black literacy continued to improve steadily, from 30 percent in 1880 to 55 percent in 1900 to nearly 90 percent by 1940. The number of black college students kept on doubling every decade. In the economic sphere, the quantum leap of black per capita income may have leveled off by 1880. But by 1910, a fourth of the black farm operators in the South owned their farms; interestingly, the figure for whites had declined to 60 percent.

This is not to deny that a serious retrogression occurred in many aspects of race relations and the conditions of life for black people. Nor is it meant to minimize the horrors of lynching, peonage, and other brutalities that disgraced this country. But the worst period of reaction was after 1890, and even then it did not entirely wipe out the gains of the first Reconstruction. Nor have the 1970s been free from important examples of regression from the gains of the 1960s. Our own decade has witnessed some forms of retreat from the second Reconstruction as distressing and consequential as the retreat in the 1870s from the first.

Consider income and employment: The median family income for blacks increased from 49 percent of that for whites in 1958 to 62 percent in 1970, but declined to 59 percent by 1976. From 1965 to 1969 the median income in constant dollars of black families increased 32 percent, but from 1969 to 1973 it barely kept pace with inflation, and since 1973 it has declined. The proportion of black households headed by women (whose income is lower than men’s) increased from 24 percent in 1965, at the time of the Moynihan Report, to 40 percent in 1978. From the Korean War to the mid-1960s the unemployment rate for blacks averaged more than twice that for whites. In the late 1960s this ratio began to decline, reaching a low of 1.7:1 in the mid-1970s. But in the last four years it has climbed again, and for the past year it has hovered around 2.3:1, an historic high. In the mid-1950s black and white teenagers had about the same level of unemployment; today the black rate is 2.7 times the white rate.

To be sure, the total economic picture for blacks is not this bad. There have been significant gains in the percentage of blacks holding professional, white-collar, and skilled-labor jobs. But even here the rate of gain has slowed or stopped in recent years. And the situation for black people outside these privileged categories is often bleak. It would seem impossible to argue that the economic improvement of the black population, measure as the degree of change, has been greater in the second Reconstruction than the first.

What about school integration? This has been one of the most significant achievements of the second Reconstruction. The first Reconstruction had nothing to match it, for with very few exceptions — some of the New Orleans public schools, the University of South Carolina, and Berea College — there were virtually no integrated schools in the South a century ago. One might speculate that the opening of schools of any kind to blacks in the first Reconstruction meant more than desegregation in the second. But let us grant that the integration of schools in the last 20 years has been an important accomplishment. Granting this, I would go on to insist that the much-discussed “white flight” from the public schools constitutes a major retreat from the goals of the second Reconstruction. If the withdrawal of troops from the South was the Compromise of 1877, the withdrawal of whites from integrated public schools is the compromise of the 1970s.

White flight has taken two forms: an acceleration of the movement of whites from cities to suburbs, and the transfer of white children from public to private schools. The busing of students across district lines in recent years has caused an increase of white flight, producing in many areas the opposite of what was intended — racial balance in the schools — by driving whites out of the public schools. Integration, after all, becomes impossible when there are virtually no whites left to integrate with. Amy Carter notwithstanding, only a handful (about 3 percent) of Washington’s public school students are white. The percentage in Newark is not much higher. From 1972 to 1975, some 40,000 white students left the Atlanta public schools, leaving them now nearly 90 percent black. Public schools in Baltimore, Chicago, Detroit, New Orleans, St. Louis, San Francisco, and some other large cities are now 75 percent or more non-white.

Nearly half the white students have left the Boston public schools since the busing controversy erupted in 1973. The white flight from the Dallas and Louisville public schools was of almost equal magnitude as they underwent “integration.” More than 130,000 white students have left the Los Angeles public schools in the past six years. The school population there is now only one-third Anglo-Caucasian; by 1985 it is expected to decline to 15 percent. In 1954, the year of the Brown decision, only one of the 20 largest cities (Washington) had a white minority in its public schools; today whites are a minority in the schools of 17 of the 20 largest cities, some of which seem headed for an apartheid school system.

This process is not confined to large cities. Pasadena, California, began the first court-ordered busing program in the nation nine years ago. On the eve of busing, five of the 32 schools in the system were more than 80 percent black and eight were more than 90 percent white. Today all of the schools are more or less equally multi-racial. To that extent, busing has been successful. But so many white parents have taken their children out of the Pasadena public schools that the “Anglo-Caucasian” appears to be an endangered species there. During the past nine years white enrollment has declined by 55 percent while the number of black and other minority students has increased 25 percent. A decade ago Pasadena’s public schools were nearly two-thirds Anglo-Caucasian; today they are two-thirds non-Anglo, and there is little reason to believe that the process wills top. Pasadena’s experience is being replicated in many other middle-sized cities.

Private schools have been the beneficiaries of white flight. Their enrollments tripled in three years at Memphis and doubled in five years at Charlotte, North Carolina, when these cities underwent court-enforced busing. Nearly half the white students in Pasadena now attend private schools. National trends are in the same direction, though less spectacularly. From 1969 to 1973 enrollments in private independent secondary schools declined because of rising costs, but in the next three years mushroomed by more than 23 percent despite inflation and recession while white enrollment in public schools declined.

Middle-class whites are leading this headlong flight from the public schools. University professors with liberal instincts who supported the civil rights legislation of the 1960s, who backed George McGovern in 1972, who have worked for good causes all their lives, are often among the first to take their children out of the public schools. In Pasadena, some of the clergymen who signed a pastoral letter endorsing busing have put their own children in private schools. In Washington, officials of the Justice Department, HEW, and other federal agencies who administer and oversee national integration efforts would not think of sending their own children to the D.C. public schools. “Quality of education” and “violence” are often cited as reasons for transferring children out of public schools. These are honest and genuine concerns, but it is a fair question whether they are any the less “code words” for racial fears than George Wallace’s slogan of “crime in the streets” a decade ago.

If the public schools are the “disaster area” of American life, then those middle-class liberals, intellectuals, clergymen, and university professors who have withdrawn their children from them bear part of the responsibility for the disaster. The absence of these highly motivated, achievement-oriented children and their parents from the school system has much to do with the decline of public education. This “bright flight” has caused a sharp decline in the average scores of many school districts in standardized national tests. Just as some Northern liberals in the 1870s abandoned Southern blacks to their fate in the first Reconstruction, so liberals today are abandoning the public schools to a similar fate in the second.

Prominent supporters of radical Reconstruction in the 1860s came to the conclusion by 1877 that the national government had tried to force too many changes too fast in the South. They called for a period of benign neglect in racial policy; they began to argue that “intractable” social problems could only work themselves out gradually, that big government and national “solutions” had failed. There is an uncanny similarity between the rhetoric of that day and our own. “The basic lesson most of us have learned from the 1960s,” wrote a disillusioned white critic in 1977, “is that the great majority of the publicly funded programs then begun were utter fiascos. Without accomplishing anything for the poor, they enriched poverty-program bureaucrats, while crime was increasing, once-stable neighborhoods were being destroyed, schools became jungles, business left in disgust, and the middle class fled in despair.” With some changes in wording but not in spirit, this statement could have appeared in Harper’s Weekly, the Nation, the New York Tribune, or numerous other journals that spoke for Northerners disillusioned with the first Reconstruction a century ago.

I do not mean to suggest that we are about to experience an abandonment of the second Reconstruction or that the reaction of the 1890s will repeat itself in the 1990s. I do mean to suggest that an interpretation of the first Reconstruction which denies the occurrence of meaningful change and contrasts that era unfavorably with our own if off the mark. It is true that white Americans a century ago were less enlightened than we are today in matters of race, economics, and the role of government in social change. Black Americans were then mostly illiterate, propertyless, and still bound by the psychological bonds of slavery. Given this disparity in knowledge and resources, it is remarkable that our ancestors accomplished so much and we so little.

--

James M. McPherson, acting chairman of the History Department, is author of The Abolitionist Legacy: From Reconstruction to the NAACP and Marching Toward Freedom: The Negro and the Civil War.

This was originally published in the February 26, 1979 issue of PAW.

No responses yet