[S]ome critical problems of the new nation were solved. The American Revolution formally ended with the arrival from Paris of the final peace treaty with Great Britain (until then, British troops still occupied New York City). Congress decided the course of settlement across the Appalachians, signed its first treaty with a neutral foreign country, and officially thanked George Washington for his services as commander-in-chief. Thomas Paine, John Paul Jones, Baron von Steuben, Nathaniel Greene, and Thomas Jefferson visited town, as did throngs of others ranging from local farmers to foreign dignitaries.

A visit from the Dutch ambassador, Pieter Johan Van Berckel (depicted on PAW’s Oct. 5, 1983, cover), was particularly appropriate, given the Dutch inspiration for Nassau Hall’s name. Read more about Princeton’s brief and improbable stint as the nation’s capital in Escher’s story from the PAW archives.

When Princeton Was the Nation’s Capital

By Constance Escher

(From the Oct. 5, 1983, issue of PAW; the story also appears in The Best of PAW: 100 Years the Princeton Alumni Weekly.)

On June 30, 1783, the secretary of the Continental Congress, Charles Thomson, wrote to his wife, “With respect to situation, convenience & pleasure I do not know a more agreeable spot in America.” He was describing the village of Princeton, New Jersey, which had just become the seat of government of the fledgling United States.

Thomson was much less impressed by Princeton’s suitability as a national capital after seeing Nassau Hall, however. His first visit to the building where Congress would meet for the next four months “had the effect of raising my mortification & disgust at the situation of Congress to the highest degree. For as I was led along the entry I passed by the chambers of the students from whence in the sultry heat of the day issued warm steams from the beds, foul linen & dirty lodgings of the boys. I found the members [of Congress] extremely out of humour and dissatisfied with their situation.”

During the few months that Congress met in Princeton, some critical problems of the new nation were solved. The American Revolution formally ended with the arrival from Paris of the final peace treaty with Great Britain (until then, British troops still occupied New York City). Congress decided the course of settlement across the Appalachians, signed its first treaty with a neutral foreign country, and officially thanked George Washington for his services as commander-in-chief. Thomas Paine, John Paul Jones, Baron von Steuben, Nathaniel Greene, and Thomas Jefferson visited town, as did throngs of others ranging from local farmers to foreign dignitaries. The events were as exciting as the setting was unlikely.

The Congress came to Princeton from Philadelphia, where it had been headquartered throughout the Revolution except during those periods when the British occupied the city. Philadelphia was then the country’s largest, most cosmopolitan center. Princeton was a war-ravaged village of only 50 to 60 houses and not more than 300 people. The move in 1783 from Philadelphia’s urbanity to Princeton’s rusticity was a dramatic one—prompted by a dramatic event.

Congress made the decision to leave Philadelphia on the evening of Saturday, June 21, 1783. Earlier that day, as its members departed from a special session at the Pennsylvania State House (Independence Hall), they had run a gauntlet of jeers and insults from a small group of mutinous Continental soldiers who were demanding their long-overdue back pay from the state government. Congress had then been further insulted by the refusal of Pennsylvania authorities to turn out their own local militia to disperse the Continentals and put down the mutiny. Mortified, the delegates forgot their habitual factionalism and voted unanimously to adjourn across the Delaware to New Jersey.

According to Kenneth R. Bowling, associate editor of the Documentary History of the First Federal Congress Project at George Washington University, there were deeper currents beneath the vote than were first evident. He notes that Congress was then divided into decentralists favoring strong state governments and centralists favoring a stronger federal government.

The decentralists, viewing Philadelphia as a stronghold of centralist sentiment, had wanted to relocate the seat of government all along. The centralists had had no such intention, until the soldiers’ demonstration on June 21. Yet the protesting troops had expected to find Congress’s chamber in Independence Hall empty, as was normal on a weekend. Only because certain centralists, including Alexander Hamilton, had called an unusual Saturday meeting did Congressmen and soldiers come face to face, with the consequent ruffling of Congressional dignity. Bowling suggests the centralists may have called the session in the hope that a confrontation would occur that might stimulate badly needed public support for Congress.

To whatever extent the event was staged and whatever it may have done to point up Congress’s weakness under the Articles of Confederation, it did serve to propel Congress to Princeton within the week. The delegates had actually voted to adjourn to either Trenton or Princeton, leaving the final choice to the president of the Congress, Elias Boudinot. A trustee of the College of New Jersey and a former resident of the town whose sister still lived there, he quickly chose Princeton. It was a natural choice in light not only of Boudinot’s personal preferences but also of more fundamental considerations, such as the prestige among republicans of John Witherspoon and his “colledge.”

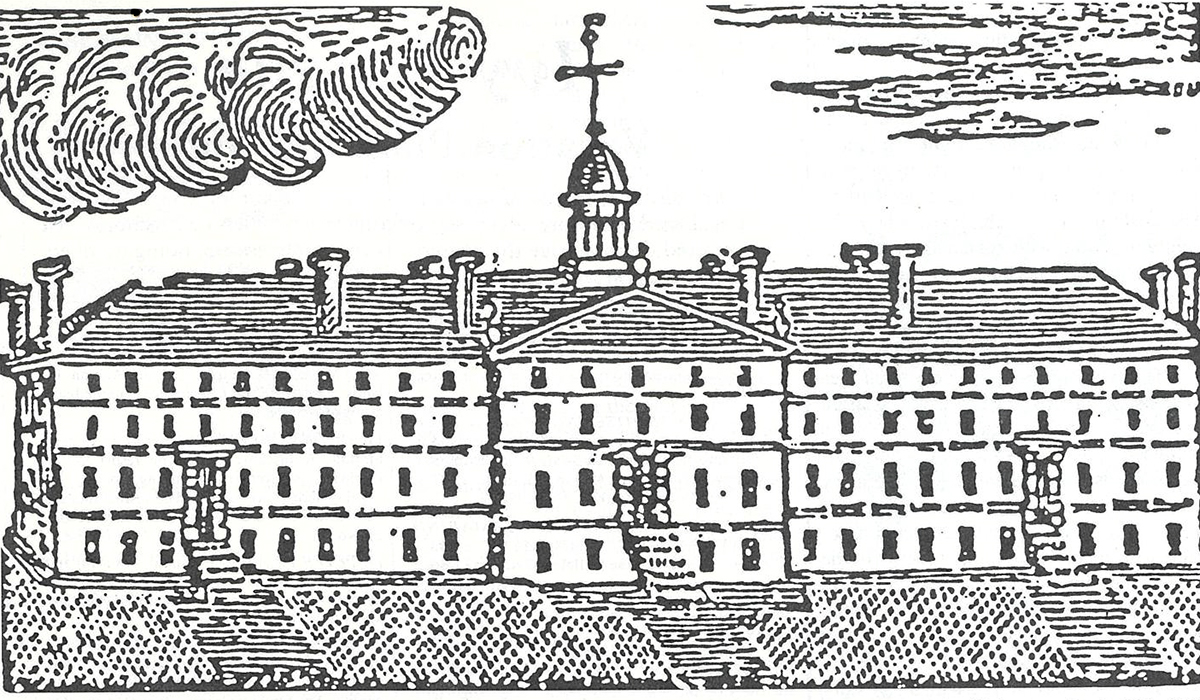

The College of New Jersey at Princeton had come to the forefront of the Revolutionary cause soon after Witherspoon assumed its presidency in 1768. On the night of his arrival from Scotland, Nassau Hall was prophetically “illuminated by a tallow dip in every window.” A new era of college life was beginning.

It was an era marked first by dedicated teaching. The fiery if paunchy Witherspoon, who spoke with a singular Scottish accent, was loved by his pupils. He taught upperclassmen divinity, rhetoric, history, and moral philosophy—which, under him, was a course in political theory—imbuing them with some of the more advanced ideas of l8th-century rationalism, as interpreted by a Scottish “common sense” philosopher. Witherspoon was, quite simply, a giant of the American Enlightenment, whether measured by his own accomplishments or those of the students he taught.

An idea of the quality and nature of Witherspoon’s mind can be derived from a look at his personal library. Browsing through some of the 300 volumes he brought to Princeton and others he later acquired, we would find not only the ancients (in their original tongues, of course), but Erasmus, Calvin, Descartes, Hume, Voltaire, Burke, and Locke.

There was nothing unusual in the fact that Witherspoon admired Locke’s writings and advanced his ideas in college lectures: Locke’s notion of a chosen contract, under the laws of nature and nature’s god, was in the tradition of English legal and political studies. The college president and his students, though, were to carry the words into action on a scale that gives special significance to another title tucked into Witherspoon’s collection—Great Britain’s Collection of the Several Statutes … now in force relating to high treason, printed in Edinburgh in 1746.

For its day, Witherspoon’s library was very complete in examination of contemporary political questions. His pamphlet collection, typically presenting all sides of current issues, included many items sent to him by alumni, friends, benefactors—anyone, we may suspect, whom Witherspoon could cajole into a small printed donation. Thus, Thomas Paine’s Common Sense stood alongside its Loyalist rebuttal, Plain Truth.

Witherspoon’s lectures, based in part on his extensive reading and his own commentaries, were augmented by debates and orations in college and in the newly formed student clubs, the American Whig Society and the Cliosophic Society. These “colleges within colleges,” as one historian has termed them, conducted their own lectures and debates and collected libraries that rivaled or outstripped the college’s own. Membership meant a real chance to practice the 18th-century tools of the educated man: refinement of the written and spoken word.

From the early 1770s on, moreover, these tools were increasingly turned to political ends as president and students alike caught “Revolutionary Fever.” Newspapers throughout the colonies took note when the senior class patriotically wore “American cloth” on Commencement Day in 1770, and when the students conducted their own tea party in 1774, burning Governor Hutchinson of Massachusetts in effigy, tolling the bell, and making many spirited resolves.

Commencement Day became a time to air the college’s Whiggish politics. Gone was a scholar’s oration of 1761 entitled “The Military Glory of Great Britain.” It was replaced by “The Rising Glory of America,” delivered in 1771 by Hugh Henry Brackenridge, a member of Whig.

Soon students were marching off to war, many before graduation. Witherspoon himself took leave in the spring of 1776 to serve in the First Continental Congress, where he signed the Declaration of Independence, the only clergyman to do so. He was to serve for six years, visiting Princeton sporadically to oversee the college’s affairs, which largely devolved to his son-in-law Samuel Stanhope Smith 1769.

During the war, however, Nassau Hall paid dearly for its politics, probably suffering more damage in the Revolution than any other college. The scientific apparatus, the college library, and the architectural fabric of the building itself were all vandalized. On January 3, 1777, in the course of the Battle of Princeton, Nassau Hall changed hands three times. Library books were torn up and used to start fires, and college chairs and tables were burned as firewood.

One commentator writing to Thomas Jefferson about how passive the New Jerseyans seemed in the face of British atrocities exempted Witherspoon alone from his criticism:

Old Weatherspoon [sic] has not escaped their fury. They have burnt his Library. It grieves him much that he has lost his controversial tracts. He would lay aside the cloth to take revenge of them. I believe he would send them to the Devil, if he could. I am sure I would.

The pamphlets had not been burned, but Nassau Hall was a battered shell. Another contemporary account describes Princeton as a ghost town, where many houses, shops, and taverns suffered damage.

The college petitioned Congress for relief monies to mend Nassau Hall. By 1779 it had received almost $20,000, although in depreciating paper currency. And repairs were almost pointless while American troops continued to occupy the structure, at various times, as a barracks, a hospital, and a military prison, treating it no more kindly than the British. As late as 1781 the college was reminding Congress that the quartering of troops was its responsibility, for some soldiers were still in Nassau Hall.

Witherspoon knew that to rebuild the college he needed the attention and support of Congress and private individuals. The “flight” from Philadelphia to Princeton, then, was a happy circumstance for the college, offering the hope of focusing Congressional attention on the sorry fortunes of Nassau Hall. While the decision to move caught Witherspoon by surprise (he was visiting with Ezra Stiles, the president of Yale, and rushed back home), his son-in-law and deputy, Samuel Stanhope Smith, wasted no time in drafting a note of welcome to Congress on June 25 “from the inhabitants of Princeton and its Vicinity,” who pledged to provide “Comfortable Accommodation.”

This last pledge, unfortunately, was wishful thinking at its worst. Princeton was too small and too rural to fulfill Congress’s needs, let alone suit its tastes. The situation became clearly less tolerable as more and more delegates drifted into town in late June and early July. The few good houses could by no means accommodate all the delegates. James Madison 1771, as a latecomer to the session, ended up sharing a room which he described to Thomas Jefferson as being so small that he was “obliged to write in a position that scarcely admits the use of any of my limbs.” Not only were Princeton’s accommodations small, they were also widely dispersed. New York’s Hamilton was quartered at Thomas Lawrence’s house, now “The Barracks” on Edgehill Street. Pennsylvania delegate Thomas FitzSimons was put up more than a mile to the south of town, while the Maryland delegates stayed, as Thomson reported, “about a mile distant on the road to Brunswick. The rest are scattered up and down the village.”

As early as June 30, in fact, Thomson found that Boudinot himself was regretting his choice: “He said freely that this place would not do. The people had exerted themselves & put themselves to inconveniences to accommodate the members but it was a burden which they could not bear long.” Boudinot initially entertained and presumably lived at Morven, the home of his sister Annis, widow of Richard Stockton 1748, a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

A further problem was the inability of most Princeton residents to supply meals, even where they could provide small rooms. This proved a continual stumbling block to the progress of official business. The Congressmen were used to Philadelphia’s fine taverns, which were unofficial offices and centers of commerce and news, where government business could be informally discussed over dinners on a regular basis. Delegates found Princeton’s two or three taverns small and cramped. As Thomson related to his wife in a letter dated July 3, “I have the honor of breakfasting at my lodging, of eating stinking fish & heavy half baked bread & drinking if I please abominable wine at a dirty tavern. On Monday indeed I got some pretty good porter, but on Tuesday the stock was exhausted, and yesterday I had the honor of drinking water to wash down some ill cooked victuals.”

As the heat and humidity of a Princeton summer descended on the village, complaints were heard everywhere. On July 25 Thomson wrote, “many of the members are heartily tired of the place and wish earnestly to remove. Yesterday they complained bitterly of being almost stewed and suffocated the night before in their small rooms.”

Stagecoach service, an important link with the outside world for both passengers and mail, was equally affected by the heat—some horses “dropped down & died & the rest came in [to Princeton] excessively jaded. It was the same with the stages from Elizabeth town, which were obliged to leave the passengers on the road, some of whom walked into this town through the broiling sun… .”

As tempers rose with the heat, factionalism reared its ugly head. The Colonial idea of “Join or Die,” symbolized by a snake in 13 sections, was forgotten. Again and again, Thomson, the only person to serve continuously in Congress from 1774 to 1789, sensed a growing likelihood that the young Confederation would break up: “And I confess I have my fear, that the prediction of our enemies will be found here, that on the removal of common danger our Confederacy and Union will be a rope of sand.” Thomson gave his educated guess as to the future: New England would be joined by New York as one state; New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Maryland would form another; Virginia would “set up for itself,” possibly with a royal governor; and South Carolina would join a southern confederacy of states.

Even at the best of times, Congress was factionalized, but part of the reason for this session’s bad tempers lay in the fact that it was so sparsely attended. Ultimately 12 states—all except Georgia—sent representatives, but during the first several months especially, Congress had trouble mustering the quorum of nine states needed to transact any important business. Moreover, some of the most able members such as Jefferson and Hamilton attended only briefly or not at all. As a result, delegates gathered day after day in Nassau Hall’s second-floor library or in Colonel George Morgan’s farmhouse at Prospect, only to adjourn.

Despite the problems of scarce accommodations, bad food, and infrequent quora, Congress did manage to plow through some business. After weeks of waiting, news arrived in July of the Treaty of Paris, signed on terms highly favorable to the United States. Later that month, moreover, Congress was able to open diplomatic relations with Sweden, the first neutral European country willing to recognize the United States. The necessary votes were produced, according to Thomson, when “Mr. Hamilton called on his way home so that for about one hour 9 states were represented in Congress. The short interval was imposed to ratify the treaty with Sweden. As soon as this was done, he left Congress and proceeded to his state so that we have now only 8 states in town.”

In July Congress also asked General Washington to come to Princeton to receive its thanks for his services during the war. Unspoken behind its request lay Congress’s desire for the prestige of his presence during a troubled time and its need for his advice on the peacetime military establishment. Washington arrived the following month and made his own headquarters at Rockingham, a rented house located about five miles north of Princeton in the even smaller village of Rocky Hill. On August 26, escorted by a small troop of cavalry, the tall and stately general rode up Nassau Street to the cheers of the citizens. He was given an audience with Congress, the details of which had been decided in advance to ensure that the civil authority of Congress was seen to take precedence over Washington’s military authority.

According to plan, the General stood and bowed to his audience, which “returned the bow, seated. As president of the Congress, Boudinot had “heightened his seat [with] a large folio to give him an elevation above the rest,” and he kept his tricorn hat on. Washington then stood again while Boudinot read the speech of welcome and gratitude. The formalities over, everyone adjourned for a festive reception.

Social life in Princeton, in fact, took a decided turn for the better over the next few months as hostesses vied for the attention of Washington, who remained nearby to meet with Congressional committees, although real work on a peacetime army was shelved for other issues. In October, Congress would simply decide to disband all the furloughed soldiers, leaving a few men at West Point and a few at Philadelphia to constitute the nation’s peacetime defense.

On September 15, Congress settled an item of business that was to have far-reaching effects. It accepted Virginia’s cession of her western claims and decided that these lands beyond the mountains would in time be divided into “distinct and separate states” and be members of the “Federal Union,” enjoying all its benefits. This set the precedent that future states would be admitted to the Union on an equal footing with the original 13.

Even though Thomson often noted fretfully, “Another day spent in ill humor and fruitless debates,” the fall saw the enactment of several other significant resolutions. One topic of in-tense debate was the location of a permanent capital for Congress itself. The Middle Atlantic states each entreated Congress to settle within their borders and opposed plans of every other state to accomplish the same goal. Because of the new commerce, construction, and culture which it was felt must accompany a “capitol seat,” the residency question was one of the most acrimonious—and longest—discussions Congressional delegates entertained.

Sites on the Hudson, the Potomac, and the Delaware rivers were heatedly considered again and again. Germantown, Pennsylvania, made an especially attractive offer. Then a site on the Delaware was chosen—to be called “Statesburg,” said Thomson. This would have placed the capital near the center of population as it then existed, but north of the United States’ geographical center.

The Southerners protested, lobbied, and eventually won the concession that two permanent seats would be designated. In addition to the “federal town” to be built “near the falls of the river Delaware,” a second city would be established “at the lower falls of the Potomac.” It was not a practical compromise—but it did open the wedge for what would become Washington, D.C.

Meanwhile, ignoring the petitions of Princeton citizens that it remain for the winter, Congress decided to rotate its seat temporarily between Annapolis and Trenton. Philadelphia still had not been forgiven, but everyone had had his fill of Princeton.

As the time for departure from Princeton approached, the delegates still had numerous issues to face, such as the treatment of Indian lands. In mid-October Congress settled this by exerting its authority and issuing an ordinance forbidding any citizen from privately purchasing lands from Indians without first receiving approval from the federal government. In some respects more difficult to resolve was the question of how to welcome the Dutch Ambassador with a proper degree of pomp and dignity. For weeks before his actual arrival, various members of Congress wrung their hands over the official reception for this ally. Even alumnus Madison had commented sarcastically on the “charming situation”—a rural village—in which Congress awaited his arrival.

The minister, Pieter Johan Van Berckel, was to land in Philadelphia—where Congress was to have secured for him a large house in a fashionable section of town—and then proceed to Princeton. These plans fell through because of the awkwardness of long-distance negotiations, with the result that Van Berckel found no residence awaiting him but was forced to stay at City Tavern (Second Street near Walnut). Although it was clean and served excellent food, City Tavern hardly afforded the space and privacy the Minister Plenipotentiary expected.

While Congress debated whether the present body or the soon-to-be-elected delegation should officially receive Berckel, Witherspoon seized the opportunity to greet the minister from William of Nassau’s own country:

The trustees of the college of New Jersey beg leave to congratulate your excellency on your arrival in this country. The name by which the building is distinguished in which our instruction is conducted, will sufficiently inform your Excellency of the attachment we have ever had to the States of the United Netherlands. [We wish you] all happiness, comfort, & success in your present important mission.

Congress granted Van Berckel an audience and a reception, but he spent the preceding night as John Witherspoon’s guest.

At a dinner party in late October, the representatives joked about the qualities needed to be a member of Congress. Eldridge Gerry of Massachusetts put forth his notion that a man had “to be a salamander or leave Congress.” Thomson recounted, “I told him, if Gentlemen continued in the disposition that they had lately discovered it would be proper to learn the use of the sword and come armed to Debate.”

But even under the adverse circumstances of their stay at Princeton, and during an awkward pause between war and for-mal peace, these homesick men carried on in common service to their country. Working within the framework of a new kind of government, the weak contract of states established by the Articles of Confederation, they struggled to forge a stronger form of republicanism.

Some of Witherspoon’s young men had gone to their deaths in the Revolution, but many more lived and served the new nation. In his Commencement address in September 1783, Ashbel Green spoke before Congress and General Washington of the moral education he had received at Princeton:

The youthful mind is taught to look into its capacity, its qualities and its powers, and to reason from them to the being and attributes of their Creator, and thence to deduce the nature and sanction of the moral law. Hence the rights of men are derived, either as individuals or as societies. We view mankind as the subjects of one great lawgiver, as the children of one common father, and we acquire the principles of universal justice and benevolence.

Green was congratulated on this speech by none other than Washington, in a chance meeting in the corridors of Nassau Hall.

In November 1783, the Congress left for Annapolis. Years later, remembering the battered state of Nassau Hall, some delegates would send the college gifts of money and books.

2 Responses

Norman Ravitch *62

7 Years AgoWhat About New Jersey Tories (or Loyalists)?

Of course we are all patriots, but if Southerners can still rally to The Lost Cause with some enthusiasm, why can we not try to see the views of the Loyalists during the American Revolution? Why is Benedict Arnold considered a traitor when he was simply loyal to his allegiance to the Crown? Of course the victors determine the historical record. But the revolutionaries were largely motivated by as many selfish as altruistic things, like non-interference with slavery, the three-way trade in slaves, molasses and sugar, the non-payment of taxes to support the British army which protected them from the French and their Native American allies, the residue of the Puritan Revolution with its bitter anti-Catholicism, ambitions in Canada, etc., etc. I remember Robert R. Palmer at Princeton in the late '50s remarking that America was lucky its anti-revolutionaries fled to Canada or the West Indies or Europe. The anti-revolutionaries in France returned after 1800 and 1815 and became a force for reaction for more than a century -- right up to 1944. Some of their supporters are still there!

Campbell Gardett ’68

7 Years AgoMake 'Archives' a Regular

I hope you will make PAW Archives a regular periodic feature. This was an outstanding article which, as it happens, I had not seen previously. Thanks for your work.