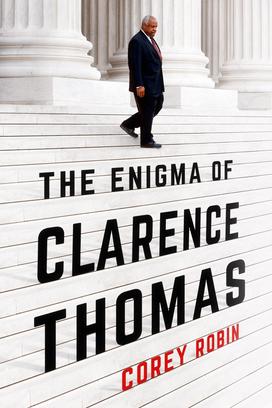

Corey Robin ’89 Explains the Enigmatic Clarence Thomas

The book: While most people know Clarence Thomas for his salacious confirmation hearing and for his laconic courtroom mien, author and political scientist Corey Robin ’89 sheds new light on the Supreme Court justice in The Enigma of Clarence Thomas (Henry Holt). Robin, a well-known analyst of right-wing ideology, uncovers how Thomas’ biography and his black nationalist writings and speeches in college created the foundation of his conservatism. Thomas’ view that there is no cure for white supremacy betrays his cynical stance toward the possibility for progress — a stance that, Robin argues, informs much of the nation’s politics today.

The author: Corey Robin ’89 is the author of The Reactionary Mind: Conservatism from Edmund Burke to Donald Trump and Fear: The History of a Political Idea. He teaches political science at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center. Robin’s writing has appeared in The New York Times, The New Yorker, Harper’s, and the London Review of Books, among other publications, and has been translated into 13 languages. He lives in Brooklyn, N.Y.

Ever since he became a candidate for the Court, Thomas has spoken to and for the most revanchist elements of the American right. During his Senate confirmation hearings, his nomination was championed by Republican operative Floyd Brown, who made the notorious Willie Horton ad that helped sink the presidential campaign of Michael Dukakis. After George H.W. Bush’s election in 1988, Brown formed a new organization to advocate for Bush’s Supreme Court nominees. He called it Citizens United. Throughout the Obama years, Thomas was known as the “Tea Party justice.” His blistering dissents were welcomed by many in the movement, and his wife, Virginia, worked closely with Tea Party leaders.

With the election of Trump, Thomas’s influence has grown. Not only has he authored several important opinions in recent years — about abortion and the First Amendment, the police and probably cause — but his former law clerks also play a leading role in and around the Trump regime. Ten former clerks hold high-level positions in the administration — defending Trump’s travel ban and other immigration policies in court; signing amicus briefs in Masterpiece Cakeshop, the Colorado gay wedding cake case; eliminating or rewriting Obama-era regulations — or have been appointed to the Offices of United States Attorneys. Eleven former clerks have been appointed to the federal bench, seven of them to the Court of Appeals, just one step away from the Supreme Court. No other justice under Trump has had as many clerks appointed to the judiciary.

Thomas was also a black nationalist.

When he was nearly 40 years old, just four years shy of his appointment to the Court, Thomas set out the foundations of his political vision in the Atlantic Monthly. “There is nothing you can do to get past black skin. I don’t care how educated you are, how good you are — you’ll never have the same contacts or opportunities, you’ll never been seen as equal to whites.” No moment’s indiscretion, this was the distillation of a lifetime of learning, which began in the segregated precincts of Savannah during the 1950s and continued through his college years in the 1960s. As a militant undergraduate at the College of the Holy Cross, Thomas came into contact with the tenents and practices of black nationalism and Black Power. He devoured the speeches of Malcolm X, which he listened to on records and was still reciting from memory two decades later. In the 1970s, Thomas began moving to the right. In 1981, he joined the Reagan administration, first as an assistant secretary of education and then as chair of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). Despite his political turn, Thomas has never lost touch with the racial separatism of his early encounters. “I’ve been very partial to Malcolm X ,” he told a conservative magazine in 1987, six years into his tenure in the Reagan administration. “There’s a lot of good in what he says.” On the Court, Thomas has continued to believe — and to argue, in opinion after opinion — that race matters; that racism is a constant, perhaps ineradicable feature of American life; and that the best hope for black people lies within themselves, not as individuals but as a separate community with separate institutions, apart from white people. This is the man Donald Trump has called his favorite justice.

With the conclusion of the 2018-19 term, Thomas has finished his twenty-eighth year on the Court. At the age of seventy-one, he is far younger than Justices Ruth Bader Ginsberg and Stephen Breyer, who are eighty-six and eighty-one respectively, and Anthony Kennedy, who retired in 2018 at the age of 82. Should Thomas remain on the court for another nine years, he will be the longest-serving justice in the history of the United States. His imprint will be broad and deep.

Reviews: “When Clarence Thomas took his seat on the Supreme Court, no one could have predicted that he would become both the silent justice and the most influential justice. Corey Robin’s elegant and insightful analysis shows how Thomas’s blend of black nationalism and conservatism helped him fashion a jurisprudence that will shape American life for years to come. This is the book Court watchers—which we all should be—have waited for.”

—Annette Gordon-Reed, Pulitzer Prize–winning author of The Hemingses of Monticello

No responses yet